by Kimberly Stubbs, MD, and Brian M. Merrill, MD, MBA

Dr. Stubbs is Clinical Chief Resident, and Dr. Merrill is Assistant Professor and Director of Community Psychiatry at Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine in Dayton, Ohio.

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Department editors: Julie P. Gentile, MD, and Allison E. Cowan, MD, Associate Professor, both from Department of Psychiatry, Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio.

Editor’s Note: The patient cases presented in Psychotherapy Rounds are composite cases written to illustrate certain diagnostic characteristics and to instruct on treatment techniques. The composite cases are not real patients in treatment. Any resemblance to a real patient is purely coincidental.

Abstract: Substance use disorders are widespread and cause significant dysfunction. Substance use disorders often co-occur with other psychiatric disorders. Because of this overlap, clinicians commonly encounter patients at risk for substance abuse disorders. This article reviews strategies to aid the practicing clinician in the screening, assessment, intervention, and referral of their parents at risk for substance use disorders.

Keywords: Psychotherapy, substance use disorders, addiction, counseling, addiction treatment, evidence based practices

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2019;16(3–4):11–15

Addiction disorders are highly prevalent and can have significant negative impact on the lives of patients and their families and on the community at large. Every day, more than 130 people in the United States (US) die of an opioid overdose.1 It is estimated that substance use/abuse costs the US nearly a trillion dollars annually.2 Estimates for prevalence of substance use disorders are wide ranging, but many assert that nearly half of the US adult population experience some elements of an addiction disorder.3 Given the staggering abundance of addiction disorders in the community, a clinician could expect to frequently encounter these conditions, even if they occurred in isolation in individuals without comorbid psychiatric disorders; however, addiction disorders do not usually present in isolation. Addiction disorders are frequently associated with other psychiatric disorders or are not the primary mental health concern of a patient pursuing psychotherapy. Because of the shared genetic vulnerability, epigenetic modifications, and environmental factors between substance use disorder and many psychiatric illnesses, it is not unusual for a patient with mental health issues to have a comorbid substance use disorder or vice versa.4–6

The astute clinician should be able to recognize signs and symptoms of an addiction disorder, have the skills to help a patient modulate use or seek treatment, and have knowledge of community resources that are accessible by patients with addiction disorders. Moreover, given the nature of addiction disorders, clinicians should be ready to help a patient manage the personal consequences of close interpersonal relationships (i.e., parents, significant others, siblings) experiencing addiction and must have knowledge of their own potential role in preventing addiction and its negative consequences. Therefore, because a therapist might encounter addiction disorders directly or peripherally and in various stages of consequences, he or she must be ready to intervene to help prevent and/or mitigate the consequences of addiction. In this article, we explore and discuss relevant considerations for the practicing clinician who will likely encounter patients with mental health concerns and comorbid substance use disorder.

Vignette 1

Mr. A was a 32-year-old male patient who presented to a psychotherapy assessment session after being referred by his primary care physician for anxiety. Mr. A reported that he had been experiencing a number of accumulating psychosocial stressors, including increased professional demands and the recent birth of his first child. He reported anxiety coinciding with these stressors that resulted in insomnia and irritability, which strained his relationship with his wife. He mentioned that to “wind down” after work or to get to sleep at night, he often used alcohol. He reported drinking as many as four standard servings of alcohol several evenings per week.

Therapist: Do you mind if we spend some time discussing the function of your drinking?

Mr. A: Sure. Like I said, it just helps me wind down.

Therapist: It’s common for people to feel relaxed with alcohol consumption. What are some other good things about your alcohol use?

Mr. A: I enjoy having a drink with the guys at work. It’s our bonding time.

Therapist: There’s a social component to drinking that you enjoy, and you mentioned previously that it helps you initiate sleep. Let’s look at the flip side. Are there any concerning aspects about drinking that you don’t care for?

Mr. A: I’m getting a beer belly. I’ve always been a pretty athletic guy, and I can tell I’m gaining weight, and I worry about my health.

Therapist: On the one hand, alcohol helps you to relax and has a social component you enjoy; and on the other hand, there are some health concerns that you have related to the alcohol use. On a scale of 1 to 10, where 1 is not ready at all to change and 10 is really ready to change with regard to your health, where are you?

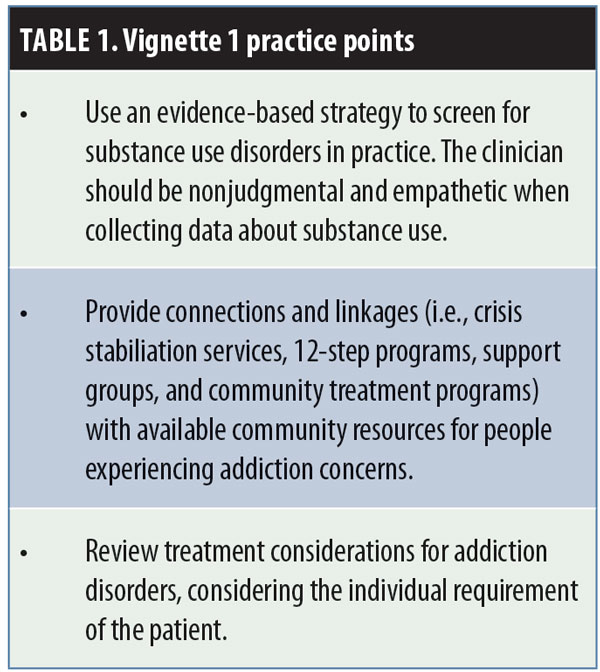

Practice Point: Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT)

Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) is an accessible and effective way to screen patients for substance use disorders, as well as counsel and refer patients with substance use disorders, that has been validated in a variety of clinical settings. SBIRT can easily be incorporated into a psychotherapy evaluation or ongoing treatment. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) offers abundant information, free of charge, on implementing an SBIRT program in clinical practice via their website (https://www.samhsa.gov).

Screening. Screening generally consists of asking the patient about the use of commonly abused substances or by administrating validated clinical screening scales. Depending on provider preference and the availability of electronic health records for data tracking, a simple, conversational quantification of a patient’s substance use pattern might provide enough clinical information. Assessments, such as Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C),7 Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10),8 and CAGE Adapted to Include Drugs (CAGE-AID),9 also can be used. Even if the clinician prefers an informal approach to screening for substance use disorders, it is imperative that every patient be asked about substance use and that any use of substances be considered an important contributor to the current constellation of symptoms. It is often appropriate and preferable to ask about substance use on a patient’s first visit, though some sensitivity might be needed due to potential resistance by the patient to disclose this information. Certainly, the development of a strong therapeutic alliance must be a priority, given its impact on outcomes.10–11

Brief intervention. In the event of a positive screen for substance use, a brief intervention is indicated. A brief intervention is a collaboration between the clinician and the patient to gauge the patient’s motivation for change and to enhance motivation.

Motivational interviewing. Motivational interviewing (MI) is based on the theory that behavioral change will follow a natural process but can be bolstered through the development of a therapeutic alliance between the treating clinician and the patient.12 Through supportive, nonjudgmental, and nonconfrontational exploration of ambivalence about substance use and examination of potential benefits to modifying behaviors around substance use, MI aims to move patients along a continuum of change toward taking action and modifying behavior. MI has four main tenets. The first, express empathy, is crucial to all modalities of psychotherapy but is especially critical when treating addiction, given the longstanding stigma associated with addiction disorders and the tendency for patients, their families, and/or prior caregivers to inappropriately conceptualize an addiction disorder as a moral failing.13 The second tenet, develop discrepancy, refers to the process of exploring differences between a patient’s future goals and aspirations and his or her current life with all of the problems arising from substance use. It might be uncomfortable for a patient to explore the impact of addiction on his or her life, but it can be a powerful motivator as the patient imagines a future without addiction and its deleterious effects. The third tenet, roll with resistance, refers to the tendency of patients with addiction disorders to be highly resistant to treatment. The resistance lies in their ambivalence about the impact of substance use on their life. Ambivalence and resistance to change are inherent human phenomena encountered in all psychotherapies, and MI provides specific interventions to overcome these barriers to change. The final tenet, support self-

efficacy, refers to the concept that for a patient to successfully overcome addiction, he or she must play a fundamental role in developing a plan to do so. The patient must feel empowered and capable of improvement. MI has demonstrated efficacy since its inception in a variety of clinical settings and for a variety of addictions.14 Clinicians from all disciplines should take time to familiarize themselves with the principals of MI because it can undoubtedly be integrated into any type of clinical practice.

Patient education. Brief interventions need not solely rely on MI. Psychoeducation about the impact of substance use on the patient’s presenting symptoms can help improve insight. Similarly, discussion of health risks, especially if this is novel information to the patient, can be helpful. Moreover, advice can be given: For example, a patient struggling with binge drinking might benefit and gain needed perspective from a discussion about the World Health Organization’s recommendations on alcohol consumption. A list of resources, including SBIRT guides, is available on the Boston University School of Public Health BNI-ART Institute website (https://www.bu.edu/bniart/).15

Referral for treatment. The final step of SBIRT is referral to treatment. For this step, the clinician should be aware of the addiction treatment infrastructure in the community where he or she practices. With this awareness, the clinician can make a patient-centered, evidence-based recommendation for the next steps in treatment. Awareness of local resources should, at minimum, consist of knowledge of local support groups for people with addiction and their families and knowledge of local treatment providers (e.g., inpatient treatment, residential treatment, crisis stabilization services, partial hospitalization and/or intensive outpatient). If a clinician commonly encounters specific addictions (e.g., opioid use disorder), then additional knowledge of office-based opioid treatment clinics also might be helpful.

Once an addiction disorder diagnosis has been established or symptoms of an addiction disorder identified, the clinician and patient should decide the appropriate course of action together. This could involve referral to a community partner, engagement in psychotherapy, or both. The severity of the addiction, degree to which it represents a serious medical issue, and the clinician’s familiarity with treating addiction are all important considerations when deciding next steps of treatment. Addictions exist along a continuum of severity and dysfunction, and the interconnected nature of addiction disorders with other psychiatric disorders is complex. Addictions can precipitate and perpetuate psychiatric disorders, and the inverse is also true. The clinician should decide on a case-by-case basis if he or she has the therapeutic alliance and the clinical tools needed to treat symptoms of addiction in his or her office or if outside help is required.

Treatment. The clinician and patient might collaboratively decide that they will first endeavor upon psychotherapy as an attempt to ameliorate presenting psychiatric symptoms, including symptoms of addiction. If this path is chosen, the clinician would be wise to use a modality with evidence supporting its use in addiction (e.g., cognitive behavioral therapy) and to continuously monitor the patient for worsening symptoms.16 Some psychotherapeutic modalities for psychiatric conditions are associated with worsening symptoms early in treatment (e.g., regression in psychodynamic therapy, worsening posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in prolonged exposure or trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy).17 If employing these

potentially activating modalities or others associated with discomfort, it is important to remain mindful that substance use patterns can change during treatment. Substance use can impede the progress of psychotherapy; thus, at times, it might be prudent to refer the patient to an intensive treatment program for addiction prior to embarking upon psychotherapy.

A nuanced approach to the patient with addiction is warranted. For example, in psychodynamic therapy, substance use could be conceptualized as representative of poor impulse control or inability to tolerate strong negative affect. These aspects of a patient’s current ego function indicate that supportive, as opposed to insight-oriented, interventions might be more appropriate for a particular patient. Despite the historical concept that behavioral interventions and insight-oriented therapy are incompatible, there is evidence supporting integration.18 An extension of this newfound integration of behavioral and insight-oriented techniques might, in the future, be a psychodynamically oriented conceptual framework for treating addiction disorders.

Vignette 2

Mr. B was a 42-year-old male patient with history of generalized anxiety disorder and depressive symptoms who was being seen for weekly psychotherapy. The patient presented to his 15th psychotherapy session visibly upset. He informed the therapist that just prior to the session, he had an intense argument with his mother. In prior sessions, Mr. B divulged that, after a period of estrangement, he recently reconnected with his mother. His ambivalence toward his mother began decades earlier. He was raised in an intact nuclear family until the age of 12 when his father died unexpectedly. Mr. B felt pressure to care for his mother after his father’s death and often worried that harm would come to his mother if he made a mistake. The female therapist treating Mr. B was aware that transference might occur, resulting in the patient being fearful about making a mistake in session. The patient noted that following his father’s death, his mother began drinking daily.

Patient: Sometimes she was in such a good mood when she drank, and I preferred it to her spending the whole day in bed. But, boy! Could she get angry at me and my sister.

Therapist: It was very unpredictable in your household growing up.

Patient: Yeah. I had to watch my step because I didn’t know what might set Mom off.

Therapist: I noticed your foot began to tap as you were talking about your mother. What is it like to share that with me?

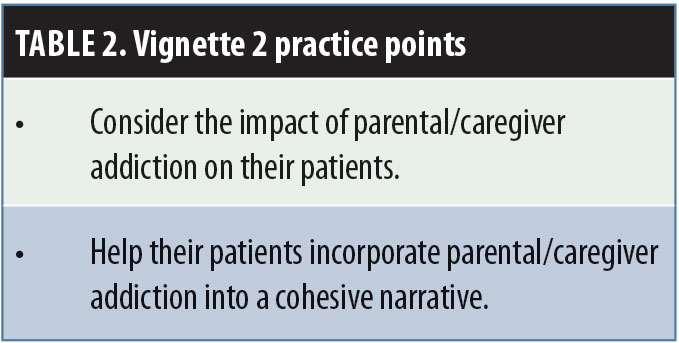

Practice Point: Treating the child of a parent or caregiver with addiction

Parental addiction can exert great influence on a child’s development. This influence can have far-reaching effects that can present as common reasons for seeking therapy later in life (e.g., anxiety, depression, interpersonal conflict). Clinical work with the child of a parent or caregiver with addiction can demonstrate the wide range of potential impacts, from the neurocognitive sequelae of intrauterine exposure and effects of substance use disorders on infant bonding and attachment to ongoing interpersonal, safety, and medical issues later in life.19 The impact of addiction on a patient can be a direct result of parental substance use (e.g., intrauterine exposure) or secondary to disturbances caused by the addiction (e.g., parental affective dysregulation, parental absence). While it is difficult to make highly generalizable process and content recommendations for psychotherapy, given the large difference between modalities, it is likely that a patient whose formative years were spend under the care of a parent or guardian with an addiction disorder will have ongoing mental health issues. Therefore, the clinician should explore this experience to help the patient incorporate relevant parental addiction content into a cohesive narrative.

Children with parents or guardians who use substances are far more likely to be the victims of physical, sexual, and emotional trauma and neglect.20,21 Thus, when a history of parental addiction is present, the clinician should probe for evidence of trauma beyond typical screening questions. When working with children in whom parental substance use is suspected, it might become necessary to make a referral to the child protective services agency in the clinician’s jurisdiction. In these cases, it is recommended that the clinician be transparent about his or her reporting requirement and openly discuss resources provided by the child welfare agency. There is a substantial body of still-accumulating evidence regarding the association of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and psychiatric disorders.22 The neurodevelopment of children and adolescents that experience the stress of domestic violence, incarcerated family members, trauma, or other factors on the ACE questionnaire can be altered in a way that confers significantly increased risk of psychiatric disorders.23,24 Because parental substance use increases the odds that a child will experience ACEs, the clinician should explore this relationship in detail to aid in underpinning a patient’s current dysfunction.

Children with parents or guardians who use substances are far more likely to be the victims of physical, sexual, and emotional trauma and neglect.20,21 Thus, when a history of parental addiction is present, the clinician should probe for evidence of trauma beyond typical screening questions. When working with children in whom parental substance use is suspected, it might become necessary to make a referral to the child protective services agency in the clinician’s jurisdiction. In these cases, it is recommended that the clinician be transparent about his or her reporting requirement and openly discuss resources provided by the child welfare agency. There is a substantial body of still-accumulating evidence regarding the association of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) and psychiatric disorders.22 The neurodevelopment of children and adolescents that experience the stress of domestic violence, incarcerated family members, trauma, or other factors on the ACE questionnaire can be altered in a way that confers significantly increased risk of psychiatric disorders.23,24 Because parental substance use increases the odds that a child will experience ACEs, the clinician should explore this relationship in detail to aid in underpinning a patient’s current dysfunction.

It might be that while the manifest content of a patient’s depression and anxiety is a stressful current interpersonal or occupational relationship, this might be a latent expression of early deprivation of positive parental interaction or extreme stress related to parental addiction. Therefore, when engaging in insight-oriented treatment, it might be especially useful to probe for the early-life impact of parental substance use to help the patient integrate the experience into his or her life in a healthy manner.

Vignette 3

Mrs. C was a 25-year-old married female patient who was seen biweekly for supportive therapy. Mrs. C had a history of opioid use disorder, was in sustained remission, and had been working with the current therapist for several months. Sessions typically began with the patient discussing recent stress involving family dynamic concerns. Mrs. C lived with her children (ages 2 and 4 years), husband, and mother-in-law. One of the goals of therapy for Mrs. C had been to identify coping skills to help her tolerate strong negative affect. Mrs. C had a significant family history of substance use concerns, and she reported past incidences of opioid misuse in an attempt to manage psychological pain. She described herself as having “a bit of a temper” and often feeling guilt and shame following angry outbursts directed toward family. The therapist encouraged Mrs. C to be introspective and curious about her own emotions.

Patient: We were leaving an open house at my son’s school, and he runs out into the street. Luckily, no cars were coming. I yelled at him for half of the trip home.

Therapist: You were pretty angry.”

Patient: I was. But then I felt guilty for making him cry. He looked terrified, and that made me sad. I don’t want him to be afraid of me like I was of my mom.

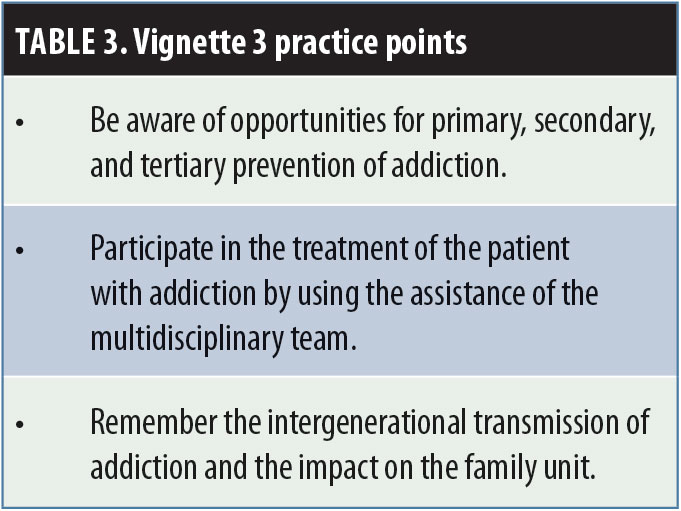

Practice Point: Addiction Prevention Techniques

Primary interventions. While many clinicians might not appreciate their roles as prevention specialists, psychotherapy can play a preventative role throughout the care continuum. Primary prevention involves use of intervention tools prior to the onset of a condition.25 Addiction is a preventable illness with known risk factors and protective factors. Parental monitoring, support, and involvement and quality of parent–child relationship have all been found to decrease the incidence of addiction.26 It is easy to see how psychotherapy with a parent could improve functioning in both child and parent. From directive interventions providing advice to parents about adequate parental monitoring to insight-oriented strategies aimed at improving dyadic relationships, a clinician has the potential to functionally improve parenting and thereby decrease the risk of addiction in a patient’s offspring.

Secondary preventions. Secondary prevention are strategies aimed at detecting an illness at the earliest stage to mitigate its consequences (e.g., routine blood pressure monitoring).25 In psychotherapy, patients should be screened during evaluation for substance use and monitored frequently for signs of substance use. Because of shared vulnerability of many psychiatric disorders and addictions, it is quite common that they occur together. Moreover, a clinician, given his or her frequent contact and presumable connection to a patient, might have the unique ability to detect substance use. As with many illnesses, early detection of substance use can lead to interventions that reduce long-term dysfunction.

Secondary preventions. Secondary prevention are strategies aimed at detecting an illness at the earliest stage to mitigate its consequences (e.g., routine blood pressure monitoring).25 In psychotherapy, patients should be screened during evaluation for substance use and monitored frequently for signs of substance use. Because of shared vulnerability of many psychiatric disorders and addictions, it is quite common that they occur together. Moreover, a clinician, given his or her frequent contact and presumable connection to a patient, might have the unique ability to detect substance use. As with many illnesses, early detection of substance use can lead to interventions that reduce long-term dysfunction.

Tertiary prevention. Tertiary prevention consists of interventions aimed at slowing or stopping illness-related dysfunction.26 Formal psychotherapeutic approaches to addiction qualify as tertiary prevention. In Mrs. C’s case, her experience of a seemingly innocuous trigger of briefly losing control of her son is intolerable. In response, she was angry and describes feeling out of control. A clinician could aid in developing affective regulation skills, which could in turn promote more effective parenting skills. These interventions, given available evidence, could reduce the likelihood that her child develops an addiction disorder later in life. A specific program for helping guide clinical work with parents is available through the SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Solutions.27

Community practice. In community practice, it is common that patients with addiction disorders are treated by multidisciplinary teams.28 A clinician treating addiction should understand the role he or she plays in the patient’s treatment plan. This can range from a private practice clinician simply being aware of resources and recommending Alcoholics Anonymous or similar self-help groups to a patient, to recommending that a patient participate in a robust substance abuse treatment program involving a team of chemical dependency specialists, peer supporters, nurses, and physicians. As part of these complex teams, the clinician providing psychotherapy should understand his or her role in providing care, and the team should determine the extent to which addiction is contributing to a patient’s dysfunction. The fundamental role of psychotherapeutic interventions is to provide support and tools that assist patients in developing healthy coping skills when faced with stressful situations rather than relying on substance use as a means of managing negative emotions.

Summary

Through complex genetic diatheses and environmental risks/triggers, addiction is intergenerationally transmitted.29 Clinicians should understand the mechanism of this transmission. The symptoms, traumatic pasts, and limitations that might compel patients to pursue psychotherapy could indeed translate into an environment that is conducive to the development of addictions in themselves and/or their offspring. Patients might use alcohol or drugs as a form of self-protection and escape from an internal world that is dangerous and intolerable. Successful psychotherapy disrupts cycles of dysfunctional defenses. A strong, therapeutic alliance and empathetic resonance between clinician and patient, patient education, and implementation of an appropriate modality-dependent interventions (e.g., insight-oriented exploration in psychodynamic therapy, cognitive restructuring in CBT) can aid the clinician and patient in identifying addressing, and reducing future use across generations.

References

- United States National Institute on Drug Abuse site. Opioid overdose crisis. Revised January 2019. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis. Accessed 6 Jan 2019.

- United States National Institute on Drug Abuse site. Trends and statistics. Last updated April 2017. https://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics. Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

- Sussman S, Lisha N, Griffiths M. Prevalence of the addictions: a problem of the majority or the minority? Eval Health Prof. 2011;34(1):3–56.

- Guintivano J, Kaminsky ZA. Role of epigenetic factors in the development of mental illness throughout life. Neurosci Res. 2016;102:56–66.

- Peña CJ, Bagot RC, Labonté B, Nestler EJ. Epigenetic signaling in psychiatric disorders. J Mol Biol. 2014;426(20):3389–3412.

- Krawczyk N, Feder KA, Saloner B, et al. The association of psychiatric comorbidity with treatment completion among clients admitted to substance use treatment programs in a US national sample. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;175:157–163.

- AUDIT-C overview. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/tool_auditc.pdf. Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

- DAST-10 Questionnaire. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/clinical-practice/DAST_-_10.pdf. Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

- CAGE-AID overview. https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/CAGEAID.pdf. Accessed 8 Jan 2019.

- Flückiger C, Del Re AC, Wampold BE, Horvath AO. The alliance in adult psychotherapy: a meta-analytic synthesis. Psychotherapy (Chic.). 2018;55(4):316–340.

- Horvath AO, Luborsky L. The role of the therapeutic alliance in psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1993;61(4):561.

- Rollnick S, Allison J. Motivational \interviewing. In: Heather N, Stockwell T (eds). The Essential Handbook of Treatment and Prevention of Alcohol Problems. West Sussex: John Wiley & Sons; 2004.

- Peele S. A moral vision of addiction: how people’s values determine whether they become and remain addicts. J Drug Issues. 1987;17(2):187–215.

- DiClemente CC, Corno CM, Graydon MM, et al. Motivational interviewing, enhancement, and brief interventions over the last decade: a review of reviews of efficacy and effectiveness. Psychol Addict Behav. 2017;31(8):862.

- Boston University School of Public Health site. A leader in using SBIRT for healthcare settings. https://www.bu.edu/bniart/. Accessed 11 Jan 2019.

- Glasner-Edwards S, Rawson R. Evidence-based practices in addiction treatment: review and recommendations for public policy. Health Policy. 2010;97(2-3):93–104.

- Cabaniss DL. Psychodynamic Psychotherapy: A Clinical Manual. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2016.

- Busch F. Psychodynamic Approaches to Behavioral Change. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing Inc.; 2019.

- Smith VC, Wilson CR. Families affected by parental substance use. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2). pii: e20161575.

- Altshuler SJ, Cleverly-Thomas A. What do we know about drug endangered children when they are first placed into care? Child Welfare. 2011;90(3):45.

- McGlade A, Ware R, Crawford M. Child protection outcomes for infants of substance-using mothers: a matched-cohort study. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):285–293.

- Herzog JI, Schmahl C. Adverse childhood experiences and the consequences on neurobiological, psychosocial, and somatic conditions across the lifespan. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:420. eCollection 2018.

- van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Potters EC, van Dam A, et al. Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) in outpatients with anxiety and depressive disorders and their association with psychiatric and somatic comorbidity and revictimization: cross-sectional observational study. J Affect Disord. 2019;246:458–464.

- Morris G, Berk M, Maes M, et al. Socioeconomic deprivation, adverse childhood experiences and medical disorders in adulthood: mechanisms and associations. Molecular Neurobiology. 2019;1–25.

- United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/pictureofamerica/pdfs/Picture_of_America_Prevention.pdf. Accessed 12 Jan 2019.

- Yap MB, Cheong TW, Zaravinos-Tsakos F, et al. Modifiable parenting factors associated with adolescent alcohol misuse: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Addiction. 2017;112(7):1142–1162.

- SAMHSA-HRSA Center for Integrated Health Solutions site. Moving beyond screening to prevent mental illness and substance use: what can be achieved in primary care? https://www.integration.samhsa.gov/about-us/esolutions-newsletter/e-solutions-august-2014. 12 Jan 2019.

- Druss BG, Silke A. Improving general medical care for persons with mental and addictive disorders: systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(2):145–153.

- Volkow ND, Boyle M. Neuroscience of addiction: relevance to prevention and treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(8):729–740.