Dear Editor:

In the 10th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) the category “acute and transient psychotic disorder” (ATPD; F23) was introduced, grouping several psychotic conditions that were originally described as separate syndromes.[1] This disorder is characterized by an acute onset of psychotic symptomatology (less than 2 weeks in duration), which is often associated with stressful events and is followed by a rapid resolution (within a period of 1–3 months).[2] Although ATPD has traditionally been associated with a good prognosis,[3] several authors question the validity of this category, given its high diagnostic instability in the long term, especially among those individuals with symptoms of schizophrenia.[4–6] Thus, less than one-third of patients with acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder (F23.2) maintain their initial diagnosis in prospective studies.[4,7] Consequently, a revision of the ATPD category for ICD-11 is considered necessary, and it is intended that those subtypes with schizophreniform features will be collected within the new F2 section under the name “Unspecified primary psychotic disorders.”[8] The present study aimed to evaluate the stability and diagnostic validity of acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder in a Spanish sample of patients.

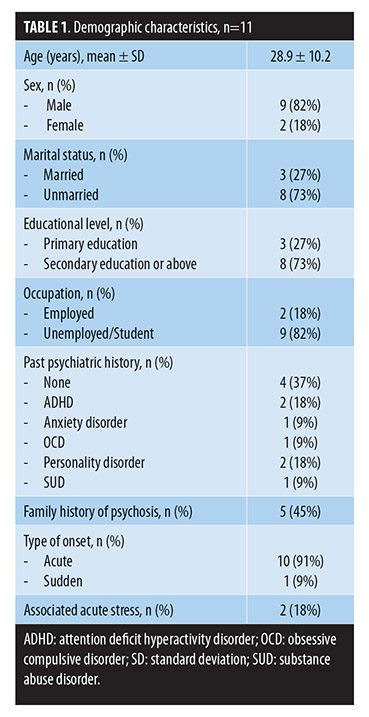

We conducted a two-year follow-up of a case series (n=11) of subjects with a first episode of acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder. All the patients were consecutively recruited from the Mental Health Services at Hospital San Juan de la Cruz (Spain) and provided their informed consent for this study. The presence of a psychotic disorder was assessed using the Spanish version of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI),[9] with the subjects selected being those that met the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria for acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder.[2] Exclusion criteria were a history of neurological or developmental disorders, traumatic head injury, or any past or present major medical illness. Demographic characteristics and clinical variables of the patients were collected at baseline (Table 1). In all the cases, the diagnosis was reviewed at three months following the onset of the psychotic syndrome and after the two-year follow-up. Diagnostic shifts were determined according to the ICD-10 temporal criteria.

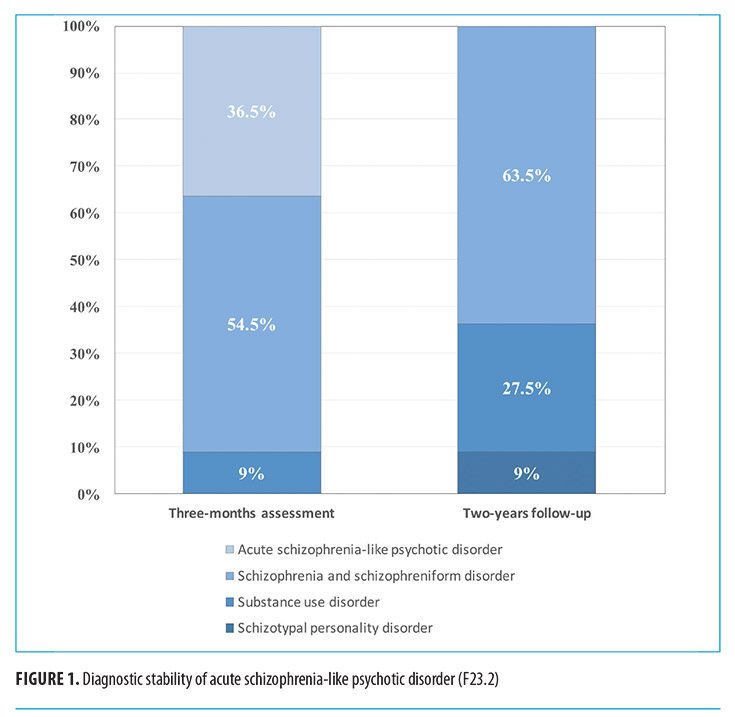

Of the 11 patients in the series with acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder, only 36.5 percent retained the diagnosis in the three months following the onset of the psychotic episode. At two-year follow-up, this proportion was 0 percent. The majority of cases (63.5%, n=7) transited to the F20 category while the others shifted to substance-induced psychosis (27.5%, n=3) or schizotypal personality disorder (9%, n=1) (Figure 1).

These results, despite the main limitation of the small sample size, undermine the diagnostic validity of acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder. Furthermore, these results lead us to consider the prognostic implications and the therapeutic management of these patients. We suggest that the coding for the disorder should be considered as provisional and those patients who are diagnosed with acute schizophrenia-like psychotic disorder should be closely monitored because their symptoms could represent a schizophrenia spectrum disorder in the early stage. Therefore, it would seem justified in these cases to perform evidence-based interventions similar to those performed on patients with first-episode schizophrenia, including interventions in terms of duration of the antipsychotic treatment as well as adjunctive psychosocial therapies with psychoeducational components to improve medication adherence and relapse prevention.

With regard,

Álvaro López-Díaz, MD; Ignacio Lara, MD; and José Luis Fernández-González, MD

Drs. López-Díaz and Lara are with the UGC Salud Mental, Hospital Universitario Virgen Macarena in Seville, Spain, and Dr. Fernández-González is with the UGC Salud Mental, Hospital San Juan de la Cruz in Úbeda (Jaén), Spain.

Funding/financial disclosures:?This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. The authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this letter.

References

- Castagnini A, Galeazzi GM. Acute and transient psychoses: clinical and nosological issues. B J Psychiatr Adv. 2016; 22(5):292–300.

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: diagnostic criteria for research. 1993.

- Marneros, A. Beyond the Kraepelinian dichotomy: acute and transient psychotic disorders and the necessity for clinical differentiation. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;189,1–2.

- Castagnini A, Bertelsen A, Berrios GE. Incidence and diagnostic stability of ICD-10 acute and transient psychotic disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(3):255–261.

- Farooq S. Is acute and transient psychotic disorder (ATPD) mini schizophrenia? The evidence from phenomenology and epidemiology. Psychiatr Danub. 2012;24(3):311–315.

- Fusar-Poli P, Cappucciati M, Rutigliano G, et al. Diagnostic stability of ICD/DSM first episode psychosis diagnoses: meta-analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(6):1395–1406.

- Salvatore P, Baldessarini RJ, Tohen M, et al. McLean-Harvard International First-Episode Project: two-year stability of ICD-10 diagnoses in 500 first-episode psychotic disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(2):183.

- Gaebel W. Status of psychotic disorders in ICD-11. Schizophr Bull. 2012;38(5):895–898.

- Bobes J. A Spanish validation study of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview. Eur Psychiatry. 1998;13:198s–199s.