by Masaru Nakamura, MD, PhD; Takahiko Nagamine, MD, PhD; Goro Sato, MD, PhD; and Kazue Besho, Phc

by Masaru Nakamura, MD, PhD; Takahiko Nagamine, MD, PhD; Goro Sato, MD, PhD; and Kazue Besho, Phc

Dr. Nakamura is with the Department of Psychiatric Internal Medicine, Kosekai-Kusatsu Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan; Dr. Nagamine is with the Department of Psychiatric Internal Medicine, Shinseikai-Ishii Memorial Hospital, Iwakuni, Japan; Dr. Sato is with the Department of Psychiatry, Kosekai-Kusatsu Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan; and PhC. Besho is with the Department of Pharmacy, Kosekai-Kusatsu Hospital, Hiroshima, Japan.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2016;13(5–6):28–30.

Funding: No funding was received for the preparation of this manuscript.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Key words: Paliperidone palmitate, paliperidone-ER, risperidone long-acting injectable, switching, prolactin

Abstract: Objective: The aim of this study was to investigate the tolerability and efficacy of paliperidone palmitate and its effect on the levels of prolactin in patients with schizophrenia.

Method: A prospective study was carried out in 22 Japanese middle-aged patients with schizophrenia who were switched from paliperidone-extended release or risperidone long-acting injectable to paliperidone palmitate for a minimum of 12 months. Psychotic symptoms using the 18-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale, extrapyramidal symptoms using 9-item Drug-induced Extrapyramidal Symptoms Scale, and plasma prolactin levels using fasting blood samples were assessed at Baseline, and one, three, six, and 12 months.

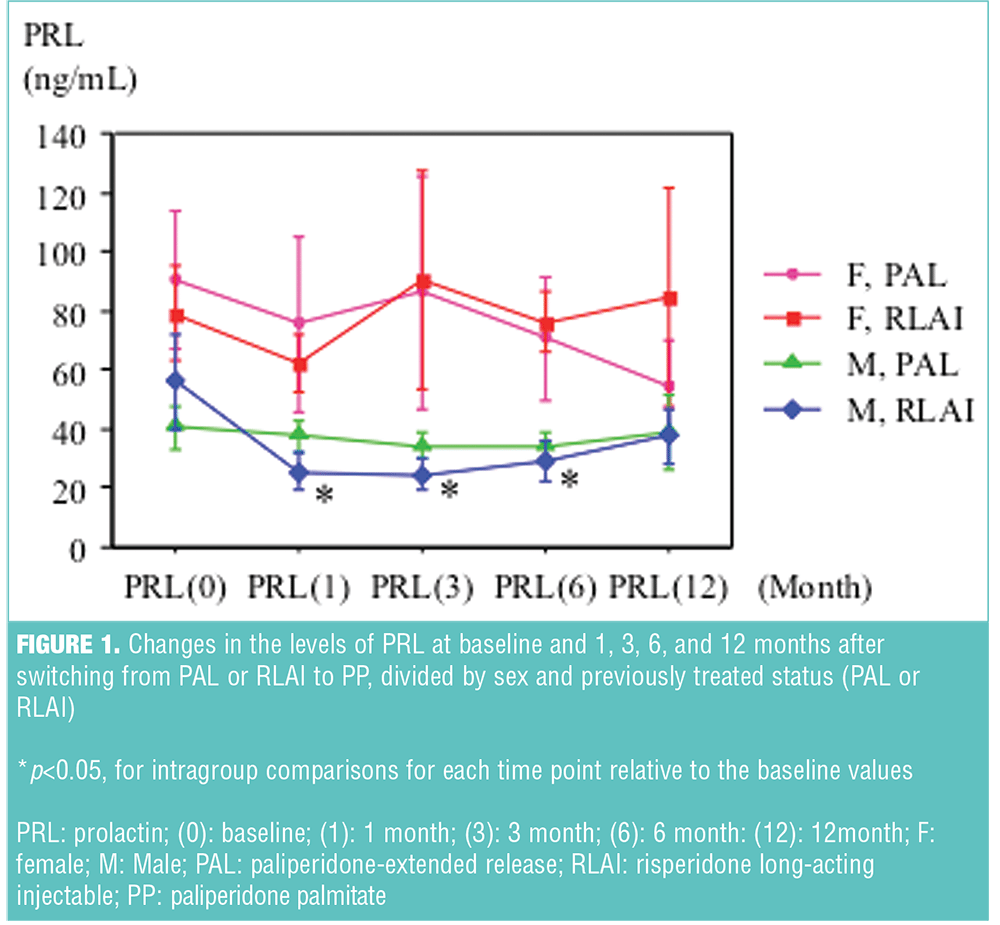

Results: There were significant reductions in prolactin levels at one, three, and six months relative to baseline in the male subjects switched from risperidone long-acting injectable, while prolactin levels in male subjects switched from paliperidone-extended release and the female subjects switched from risperidone long-acting injectable or paliperidone-extended release were largely unchanged. No time-sequential changes were observed in total scores of Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale and Drug-induced Extrapyramidal Symptoms Scale, irrespective of previous antipsychotics treatment.

Conclusion: Switching from paliperidone-extended release or risperidone long-acting injectable to paliperidone palmitate did not result in any observed time-sequential changes in psychotic symptoms in study subjects, and prolactin levels decreased in male subjects switched from risperidone long-acting injectable. As measurement of paliperidone concentrations is limited in routine practice, a fluctuation range of prolactin levels may be a useful marker for confirmation of safety maintenance treatment with long-acting injectables in clinical settings.

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a chronic and recurrent psychiatric disorder that requires long-term treatment with antipsychotics. The use of long-acting preparations has been shown to increase adherence in patients with schizophrenia, reduce their risks of relapse, and improve their global outcomes.1 Paliperidone extended release (PAL) and risperidone long-acting injection (RLAI) provide constant medication delivery offering low peak-to-trough fluctuations and significant clinical effect.[2],[3] Paliperidone palmitate (PP) is a recently developed LAI with efficacy and tolerability that have been demonstrated in randomized, double-blind, controlled studies.[4],[5] Among several oral antipsychotics, a significant association between dopamine D2 receptor occupancy levels and serum prolactin concentration has been demonstrated in previous studies.[6],[7] Here, we investigate changes in prolactin levels after switching from PAL or RLAI to PP, in a 12-month, prospective-designed study of Japanese middle-aged patients with schizophrenia. The ethics committee of Kusatsu Hospital approved this study.

Methods

Inclusion criteria. Patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)[8] that were switched from PAL or RLAI to PP based on a psychiatrist’s recommendation were enrolled consecutively in our study from December 2013 to May 2014 at Kusatsu Hospital in Hiroshima. Those patients who agreed to participate via written informed consent were eligible to enter the study. Inclusion criteria were 1) being treated with PAL or RLAI for at least six months previously and ongoing treatment with PP for 12 months or more, 2) not having changed antipsychotic treatment (neither introduction of another oral antipsychotic nor additional use of anti-Parkinson agents), and 3) fulfilled dose conversion switching method according to the technical specifications of the product.[9]

Patient assessment. A total of 22 subjects met the criteria and were then divided into groups by sex and previous antipsychotic treatment. Psychotic symptoms using the 18-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)[10] and extrapyramidal symptoms using 9-item Drug-induced Extrapyramidal Symptoms Scale (DIEPSS),[11] and plasma prolactin levels using fasting blood samples were assessed at baseline, and one, three, six, and 12 months.

Analysis. Baseline differences of mean age and total scores of BPRS and DIEPSS were evaluated using unpaired Mann-Whitney U test, and distribution of sex and previous treatment status were analyzed using the chi-square test, to be considered statistically significant at P<0.05. The prolactin levels and BPRS and DIEPSS scores were classified into four subgroups. Multiple comparisons of the measured values at baseline and one, three, six, and 12 months were performed with repeated measured ANOVA, followed by post-hoc analysis using Boneferroni adjustment, and considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

Results

Subjects consisted of seven men and six women in the PAL group, and five men and four women in the RLAI group. Baseline difference was found only in mean age in PAL subjects (54.6±7.2 vs. 43.2±11.9, p<0.05; mean±standard deviation [SD] for men and women, respectively). In male RLAI subjects, there was a significant reduction in the prolactin levels from baseline at one, three, and six months (56.0±16.4, 25.6±6.0, 24.7±5.0, 29.2±7.2; mean±standard error [SE], at baseline, and one, three, and six months, respectively), while those in male PAL group and female RLAI or PAL group were largely unchanged from baseline. The changes of their values are presented in Figure 1. There were no differences in total scores of BPRS and DIEPSS at baseline, and no statistical changes from baseline to the last observed points throughout within each subgroup.

Discussion

In our study, prolactin levels seemed to decrease in the male RLAI group, and tolerability and efficacy were not impaired after switching to PP. Two published studies suggest that prolactin levels are reduced after switching from risperidone to paliperidone in the elderly and from RLAI to PP in young patients with schizophrenia.[12],[13] These studies compared the prolactin levels between baseline and only one time point, while in our study we longitudinally examined the prolactin levels for 12 months.

It has been suggested that hyperprolactinemia in patients treated with RLAI or PP is driven by 9-hydrooxy-risperidone, and the higher occupancy of dopamine D2 at the pituitary level compared with the striatum. An analysis from a separate six-day, Phase I study in stable patients with schizophrenia found similar prolactin pharmacokinetic profiles when subjects received the highest recommendation dose of PAL (12mg/day) compared to an average dose of risperidone of 4mg/day, which was not considered “therapeutically equivalent.”[14] The peak to trough fluctuation in plasma concentration over the recommended dosing interval in PP is considered to be relatively low than that in RLAI.[15],[16] So, it is more likely that the peak prolactin levels treated with PP are less than that with RLAI. However, this pattern was not observed in female subjects, perhaps because the levels of sex hormones (e.g., estrogen, progesterone) periodically affected these subjects’ prolactin levels.

Limitations. There are several limitations to this study. First, it was an open-label study, not a double-blind study, leaving room for the possibility of bias. Second, the sample size was too small to compare prolactin levels in each subgroup. Third, the follow-up period of 12 months may not be long enough to drawn firm conclusions. Despite these limitations, this study provides useful information about the changes in prolactin levels after switching from PAL or RLAI to PP in “real-world,” long–treatment setting.

Conclusion

In conclusion, as measurement of paliperidone concentrations is limited in routine practice, fluctuation range of prolactin levels may become a useful marker for confirmation of safety maintenance treatment with LAI. Further prospective and longer follow-up studies in larger groups of subjects are required to confirm our findings.

References

1. Leucht C, Heres S, Kane JM, et al. Oral versus depot antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia–a critical systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised long-term trials. Schizophr Res. 2011;127:83–92.

2. Owen RT. Extended-release paliperidone: efficacy, safety and tolerability profile of a new atypical antipsychotic. Drugs Today. 2007;43:249–258.

3. Chue P, Emsley R. Long-acting formulations of atypical antipsychotics: time to reconsider when to introduce depot antipsychotics. CNS Drugs. 2007;21:441–448.

4. Pandina GJ, Lindenmayer JP, Lull J, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled study to assess the efficacy and safety of 3 doses of paliperidone palmitate in adults with acutely exacerbated schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30:235–244.

5. Hough D, Gopal S, Vijapurkar U, et al. Paliperidone palmitate maintenance treatment in delaying the time-to-relapse in patients with schizophrenia: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Schizophr Res. 2010;116:107–117.

6. Kapur S, Langlois X, Vinken P, et al. The differential effects of atypical antipsychotics on prolactin elevation are explained by their differential blood-brain disposition: a pharmacological analysis in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:1129–1134.

7. Arakawa R, Okumura M, Ito H, et al. Positron emission tomography measurement of dopamine D? receptor occupancy in the pituitary and cerebral cortex: relation to antipsychotic-induced hyperprolactinemia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71:1131–1137.

8. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press Inc.; 2001.

9. Gopal S, Gassmann-Mayer C, Palumbo J, et al. Practical guidance for dosing and switching paliperidone palmitate treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26:377–387.

10. Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychologic Rep. 1962;10:799–812.

11. Kim JH, Jung HY, Kang UG, et al. Metric characteristics of the drug-induced extrapyramidal symptoms scale (DIEPSS): a practical combined rating scale for drug-induced movement disorders. Mov Disord. 2002;17(6):1354–1359.

12. Suzuki H, Gen K, Otomo M, et al. Study of the efficacy and safety of switching from risperidone to paliperidone in elderly patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;67:76–82.

13. Montalvo I, Ortega L, López X, et al. Changes in prolactin levels and sexual function in young psychotic patients after switching from long-acting injectable risperidone to paliperidone palmitate. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;28:46–49.

14. Berwaerts J, Cleton A, Rossenu S, et al. A comparison of serum prolactin concentrations after administration of paliperidone extended-release and risperidone tablets in patients with schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:1011–1018.

15. Sheehan JJ, Reilly KR, Fu DJ, et al.?Comparison of the peak-to-trough fluctuation in plasma concentration of long-acting injectable antipsychotics and their oral equivalents. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9:17–23.

16. Wakamatsu A, Aoki K, Sakiyama Y, et al. Predicting pharmacokinetic stability by multiple oral administration of atypical antipsychotics. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10:23–30.