by Randy A. Sansone, MD, and Lori A. Sansone, MD

by Randy A. Sansone, MD, and Lori A. Sansone, MD

R. Sansone is a professor in the Departments of Psychiatry and Internal Medicine at Wright State University School of Medicine in Dayton, OH, and Director of Psychiatry Education at Kettering Medical Center in Kettering, OH. L. Sansone is a civilian family medicine physician and Medical Director of the Family Health Clinic at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base Medical Center in WPAFB, OH. The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Air Force, Department of Defense, or United States Government.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(3):35–39

This ongoing column is dedicated to the challenging clinical interface between psychiatry and primary care—two fields that are inexorably linked.

Funding: There was no funding for the development and writing of this article.

Financial Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Key Words: Aggressive patient, aggressive behavior, primary care, borderline personality disorder, borderline personality symptomatology, alcohol misuse, drug misuse, prescription medication abuse, mental healthcare utilization

Abstract: Aggression and violence in the medical setting appear to be on the increase. In support of this impression, a number of studies have documented surprising rates of such behavior toward trainees as well as physicians-in-practice. However, to date, these studies have focused on the experiences and reports of professionals, not patient offenders. In a series of investigations, we examined aggressive and disruptive office behaviors from the perspective of the perpetrators—the patients. Findings from these studies indicate that disruptive office behaviors by patients appear to be related to borderline personality symptomatology, alcohol/drug misuse, prescription medication abuse, and higher rates of past mental healthcare utilization. The results of these studies suggest a rudimentary psychological profile for the aggressive patient in the primary care setting.

Introduction

Patient-propagated violence in the medical setting appears to be on the increase.[1] This impression is reinforced by a number of studies that have examined the prevalence rates of patient mistreatment of healthcare professionals. At the professional level of trainees, 50 percent of physicians-in-training in seven Canadian residencies reported psychological abuse by patients.[2] In a study of residents in various training programs in New Zealand, 67 percent of participants reported verbal threats by patients, 54 percent physical intimidation by patients, 41 percent the observation of damage to the facility by patients, and 39 percent physical assaults by patients.[3] In a survey study of psychiatry training directors, participants indicated a mean of 1.26 physical attacks on psychiatric residents per program during a two-year period.[4] Other trainees, such as student nurses, also commonly report aggressive behaviors from patients.[5]

As a caveat, the preceding statistics could be partially influenced by the settings in which trainees are educated, which are oftentimes located in urban areas. However, at the level of practicing physicians, additional studies reinforce findings encountered among trainees and reveal surprising prevalence rates of patient aggression toward them, as well. For example, in a sample of practicing female Canadian physicians, during a 12-month period, 71 percent reported verbal abuse by patients and 33 percent reported physical assaults by patients.6 In two surveys of psychiatrists in the United States, 35 percent and 42 percent of respondents reported previous serious assaults by patients.[7,8] In a study of primary care physicians in the United States, 61 percent of respondents reported being bullied by a patient to write a prescription, 41 percent having had a patient removed from their office, 33 percent having been cursed at, and 10 percent having been verbally threatened.[9] In a study of Canadian general internists, three-quarters of respondents reported emotional abuse by patients, with 38 percent of female and 26 percent of male participants reporting physical assaults.[10] In a study from Spain, 58 percent of primary care physicians reported aggressive behaviors by patients, including verbal abuse (85%) and physical abuse (12.5%).[11] Given the preceding data, it is apparent that physicians-in-training and physicians-in-practice are subjected to unexpectedly high levels of patient aggression and violence. Similarly, nurses and office staff appear at least as likely as physicians to be at-risk for victimization by patient aggression.

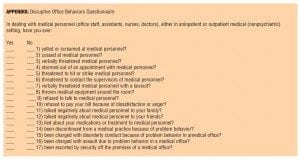

Note that all of the preceding studies are based on queries of professionals about their experiences with patient aggression and violence. Using a novel approach to this area of investigation, we explored patient violence and aggression from the perspective of the patient. In other words, what would patients have to reveal to us about their aggressive and/or violent behaviors in the medical setting? To examine this unique perspective, we examined “disruptive office behaviors” by patients in a series of studies using an author-developed inventory, the Disruptive Office Behaviors Questionnaire. This 17-item questionnaire begins with the stem, “In dealing with medical personnel (office staff, assistants, nurses, doctors), either in an inpatient or outpatient medical (nonpsychiatric) setting, have you ever…” and then queries respondents about various disruptive behaviors in the medical setting such as yelling or screaming at medical personnel, cursing at medical personnel, verbally threatening medical personnel, and storming out of appointments with medical personnel. The Disruptive Office Behaviors Questionnaire is fully displayed in the appendix, but in our investigations, this measure was headed as, “Office Behaviors Questionnaire.”

All of the upcoming data that we will present utilized the Disruptive Office Behaviors Questionnaire. The investigation took place among patients in an internal medicine outpatient setting that is predominantly staffed by resident providers. This outpatient setting is located in a suburban community in a mid-sized, mid-western city in the United States, and provides services to a significant percentage of indigent patients. The patient sample was consecutive, and all data were self-report (i.e., participants completed self-administered surveys). As a caveat, because these data were self-report in nature, some participants may not have fully disclosed their past disruptive behaviors because of, for example, shame, fear of stigma, or concerns about receiving further medical services despite anonymity. Within the same dataset, we examined various facets of patient aggression and violent behaviors in the medical setting in an effort to determine associations between these behaviors and several psychiatric phenomena.

Disruptive Office Behaviors and Borderline Personality Symptomatology

In our initial scrutiny of these data,[12] we examined relationships between disruptive office behaviors and borderline personality symptomatology. Borderline personality symptomatology was assessed using two self-report measures for the disorder: the borderline personality disorder scale of the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire-4 (PDQ-4)[13] and the Self-Harm Inventory (SHI).[14] Because these are screening measures for borderline personality and run the risk of generating false positives, we present these instruments here as assessments for borderline personality symptomatology.

With regard to results, we found that a statistically significantly greater proportion of respondents who exceeded the clinical cut-off score for borderline personality symptomatology on the PDQ-4 endorsed at least one disruptive office behavior (82.5%) compared to those respondents who did not exceed the cut-off score for borderline personality symptomatology (45.1%). Similarly, a statistically significantly greater proportion of respondents who exceeded the clinical cut-off score for borderline personality symptomatology on the SHI endorsed at least one disruptive office behavior (85.4%) compared to those respondents who did not exceed the cut-off score (43.7%). In other words, participants who were positive on either measure for borderline personality symptomatology were approximately twice as likely to report at least one disruptive office behavior in the medical setting.

In comparing those participants with a positive score on either measure of borderline personality symptomatology versus participants with negative scores on both measures, we found that several behaviors were statistically significantly more common among the participants with this specific personality pathology. These behaviors were yelling and screaming at medical personnel, verbally threatening medical personnel, refusing to talk to medical personnel, and talking negatively to family and friends about medical personnel.

Overall, findings support a relationship between disruptive office behaviors and borderline personality symptomatology. From our perspective, this is not surprising given the volatile interpersonal nature, emotional reactivity, and intolerance-to-limits that patients with this personality pathology may display.

Disruptive Office Behaviors and Alcohol/Substance Misuse

Alcohol and/or substance misuse demonstrate well-known associations with aggressive behavior among susceptible individuals. For this reason, we next examined relationships between past alcohol and drug problems (“Have you ever had a problem with alcohol?” and, “Have you ever had a problem with drugs?”) and relationships with this unique form of patient aggression—disruptive office behaviors in the medical setting.[15] In this study, we found that participants who indicated a history of alcohol problems reported a statistically significantly greater number of disruptive office behaviors in the medical setting (mean [M]=1.71, standard deviation [SD]=1.83) compared with those who did not indicate such a history (M=1.16, SD=1.42). Likewise, participants who indicated a history of drug problems reported a statistically significantly greater number of disruptive office behaviors in the medical setting (M=2.03, SD=1.76) compared with those who did not indicate such a history (M=1.15, SD=1.43).

Findings confirm that individuals with past histories of either alcohol or drug problems evidence a statistically significantly greater number of disruptive office behaviors than individuals without these types of difficulties. This finding supports the likelihood that disruptive office behaviors are but one aggressive behavior in a possible range of aggressive behaviors displayed by individuals with alcohol and/or drug misuse.

In a related vein, we next examined associations between disruptive office behaviors and the abuse of prescription medications (“Have you ever intentionally, or on purpose, abused prescription medication?”), which we consider to be a variant of general substance misuse (unpublished data). In support of this perspective, data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions indicate that prescription opioid abuse is statistically significantly associated with other forms of substance misuse, as well[16]—a finding supported by other studies.[17–19]

In this study, we found that the number of disruptive office behaviors was statistically significantly greater among respondents who had abused prescription medication (M=2.26, SD=1.45) compared to those who had not (M=1.19, SD=1.63). In teasing out between-group differences, three particular disruptive behaviors were more common among those respondents who indicated having abused prescription medication: yelling or screaming at medical personnel, refusing to pay a bill because of dissatisfaction or anger, and lying to medical personnel about medications or treatment.

Findings confirm that prescription medication abuse by patients is associated with aggressive and disruptive office behaviors in the medical setting. This finding is most likely related to syndromal overlap among alcohol, substance, and prescription medication misuse.

Disruptive Office Behaviors and Past Mental Healthcare Utilization

Given the preceding relationships between disruptive office behaviors and borderline personality symptomatology and the misuse of alcohol, substances, and prescriptions, we next wondered if there might be relationships between disruptive office behaviors in the medical setting and extent of past mental healthcare utilization.[20] To examine these relationships, we assessed four types of mental healthcare utilization (i.e., “Have you ever been seen by a psychiatrist?, Have you ever been hospitalized in a psychiatric hospital?, Have you ever been in counseling?,” and, “Have you ever been on medication for your nerves?”) and their possible relationships to the number of self-reported disruptive office behaviors.

Findings indicated statistically significant relationships between the number of reported disruptive office behaviors and having been seen by a psychiatrist, having been in counseling, and having been on medication for one’s nerves—but not having been hospitalized in a psychiatric hospital. Overall, findings support our hypothesis and indicate relationships between disruptive office behaviors in the medical setting and higher levels of past mental healthcare utilization.

Conclusion

From these overall findings, we may draw a number of general conclusions about disruptive office behaviors among primary care patients. First, disruptive office behaviors are likely to be a specific subset of behaviors that are affiliated with general aggressive behavior. This impression may explain the associations we found with borderline personality symptomatology, alcohol and drug misuse, and prescription medication abuse—all being syndromes potentially associated with aggression. In addition, because of the associations between disruptive office behaviors and a number of psychiatric syndromes, there is an understandable and associated increase in past mental healthcare utilization. Therefore, all of these findings are likely to be inter-related. These findings provide an emerging profile of the individual who is likely to be aggressive in the medical setting—a profile that has been revealed through self-report data by the offenders, themselves.

The conclusions of these studies are relevant for clinicians in terms of anticipating such behavior (i.e., these are likely to be signaling characteristics) as well as interpreting aggressive office behavior in the clinical setting. There are probably additional factors that contribute to disruptive office behaviors in the medical setting, including demographic moderators and other Axis I and II features. However, only additional research will tease out their contributory roles. For the time being, we have a rudimentary profile of the patient who is likely to be disruptive in the medical setting—a finding that is likely applicable in both primary care and psychiatric settings.

References

1. Naish J, Carter YH, Gray RW, et al. Brief encounters of aggression and violence in primary care: a team approach to coping strategies. Fam Pract. 2002;19:504–510.

2. Cook DJ, Liutkus JF, Risdon CL, et al. Residents’ experiences of abuse, discrimination and sexual harassment during residency training. McMaster University Residency Training Programs. CMAJ. 1996;154:1657–1665.

3. Coverdale J, Gale C, Weeks S, Turbott S. A survey of threats and violent acts by patients against training physicians. Med Educ. 2001;35:154–159.

4. Sansone RA, Taylor SB, Gaither GA. Patient assaults on psychiatry residents: results of a national survey. Traumatol. 2002;8:211–214.

5. Hinchberger PA. Violence against female student nurses in the workplace. Nurs Forum. 2009;44:37–46.

6. Stewart DE, Ahmad F, Cheung AM, et al. Women physicians and stress. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2000;9:185–190.

7. Dubin WR, Wilson SJ, Mercer C. Assaults against psychiatrists in outpatient settings. J Clin Psychiatry. 1988;49:338–345.

8. Madden DJ, Lion JR, Penna MW. Assaults on psychiatrists by patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1976;133:422–425.

9. Sansone RA, Sansone LA, Wiederman MW. Patient bullying: a survey of physicians in primary care. Prim Care Comp J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;9:56–58.

10. Cook DJ, Griffith LE, Cohen M, et al. Discrimination and abuse experienced by general internists in Canada. J Gen Int Med. 1995;10:565–572.

11. Moreno Jimenez MA, Vico Ramirez F, Zerolo Andrey FJ, et al. Analysis of patient violence in primary care. Aten Primaria. 2005;36:152–158.

12. Sansone RA, Farukhi S, Wiederman MW. Disruptive behaviors in the medical setting and borderline personality. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2011;41:355–363.

13. Hyler SE. Personality Diagnostic Questionniare-4. New York: 1994.

14. Sansone RA, Wiederman MW, Sansone LA. The Self-Harm Inventory (SHI): development of a scale for identifying self-destructive behaviors and borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychol. 1998;54:973–983.

15. Sansone RA, Farukhi S, Wiederman MW. History of alcohol and/or drug problems and their relationship to disruptive behaviors in the medical setting. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2012;14(5).

16. Wu LT, Woody GE, Yang C, Blazer DG. How do prescription opioid users differ from users of heroin or other drugs in psychopathology: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Addict Med. 2011;5:28–35.

17. Currie CL, Schopflocher DP, Wild TC. Prevalence and correlates of 12-month prescription drug misuse in Alberta. Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56:27–34.

18. Fenton MC, Keyes KM, Martins SS, Hasin DS. The role of a prescription in anxiety medication use, abuse, and dependence. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167:1247–1253.

19 Hakkarainen P, Metso L. Joint use of drugs and alcohol. Eur Addict Res. 2009;15:113–120.

20. Sansone RA, Farukhi S, Wiederman MW. Mental health history and disruptive behaviors in the medical setting. Int Med J. 2012;42:222–223.