by Devendra Kumar Singh Varshney, PhD; Manju Agrawal, PhD; Rakesh Kumar Tripathi, PhD, MPhil; and Satish Rasaily, MD

Dr. Varshney is with DCV Institute of Indology in Lucknow, India. Dr. Agrawal is with Amity University Uttar Pradesh in Lucknow, India. Dr. Tripathi is with DGMH, King George Medical University in Lucknow, India. Dr. Rasaily is with Singtam District Hospital in East Sikkim, India.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this article.

DISCLOSURES: The authors declare no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2025;22(4–6):38–43.

Abstract

Objective: This case series is an inaugural attempt to provide a feasible management plan for symptoms of dissociative (conversion) disorders among adolescent girls and women using pranayama, a systematic and rhythmic yogic breathing technique. Dissociative disorders are frequently reported among adolescent girls and women across different cultures and states in India. The neurobiology of dissociative disorders is not clearly understood. Hence, there is no effective medication available. There are no scientific reports available on the use of pranayama for dissociative disorders. Methods: This study presents three female patients (aged 17 years, 26 years, and 14 years) who underwent pranayama therapy instead of conventional management in outpatient settings for four weeks. A pranayama intervention module was designed based on their specific symptoms, using the Dissociative Experiences Measurement Oxford (DEMO) scale. After four weeks, the results were documented, and all three patients were advised to continue the daily practice of pranayama for 30 minutes in the morning and evening. Results: All three patients reported improvement in breathlessness, restlessness, sleep, focus and concentration, feeling numb and disconnected, memory blanks, and vivid internal world. A follow-up was done after four weeks of completion of the pranayama intervention. No adverse effects were noted during the four weeks of intervention and at follow-up. Conclusion: This case series testifies to the potential efficacy of pranayama intervention in managing the symptoms of dissociative disorders among adolescent girls and women. Further studies are required on a large sample size to validate the role of pranayama in the management of symptoms of dissociative disorders as an independent intervention.

Keywords: Conversion disorder, dissociation, dissociative disorder, pranayama, yogic breathing

Dissociation is the main characteristic of dissociative disorders.1 Dissociation is the loss of memory, identity, or one’s sense of self. The self comprises our thoughts, emotions, behavior, and memory. In simple terms, dissociation occurs when two or more psychological processes are poorly integrated.2 When a person dissociates, they feel disconnected from their self and the world around them. According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5), “Dissociative disorders are characterized by a disruption of and/or discontinuity in the normal integration of consciousness, memory, identity, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control, and behavior.”3 The International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Revision (ICD-10) classifies dissociative (conversion) disorder as dissociative amnesia, dissociative fugue, dissociative stupor, trance and possession disorders, dissociative motor disorders, dissociative convulsions, dissociative anesthesia and sensory loss, mixed and other unspecified dissociative disorders.4 Dissociative disorders are primary disorders and unlike amnestic disorders, they are never due to an underlying general medical condition.3

Dissociative disorders exhibit both commonalities and distinctions across Asian and Western populations, with research from Hong Kong highlighting the predictive nature of these symptoms in health service users.5 Furthermore, prevalence in Taiwan aligns with Western findings,6 while South Korean research enhances comprehension of dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and highlights the critical role of clinical interviews in diagnosing the dissociative subtype of PTSD (d-PTSD), potentially uncovering greater prevalence rates compared to alternative diagnostic approaches.7 Research from South Korea also indicates that the swift shift toward a Westernized, individualistic society, coupled with a rise in child abuse, can be linked to the growing incidence of dissociative identity disorder, which was previously under-recognized in this area.8

In India, the prevalence of dissociative disorders ranges from 1.5 to 15 per 1,000 individuals in outpatient contexts and 1.5 to 11.6 per 1,000 individuals in inpatient environments.9 Patients with dissociative (conversion) disorder often report symptoms such as numbness, paralysis, or seizures for which no medical evidence is found in medical tests.10 A stressful life event or a compelling personal problem typically triggers the onset of dissociative disorders. Dissociative disorders are frequently associated with childhood abuse, trauma, substance abuse, and major mood disorders. Dissociative disorders are most commonly reported among married Hindu women younger than 25 years of age residing in rural areas and having low socioeconomic status.11 In 2018, trance and possession (60%) was the most common subtype of dissociative disorder in the Dakshina Kannada district of India, followed by dissociative motor disorder.11 Another study conducted at a psychiatric institute in India over a 10-year period highlighted that the majority of patients were diagnosed with dissociative motor disorder (43.3% of outpatients, 37.7% of inpatients), followed by dissociative convulsions (23% of outpatients, 27.8% of inpatients). Higher prevalence of female sex was observed in all subtypes of dissociative disorders except dissociative fugue.12 Historically, the diagnosis and treatment of dissociative disorders have been controversial, and the etiology, pathogenesis, phenomenology, and management are controversial and debatable.13

Pranayama, a systematic and rhythmic yogic breathing technique that focuses on breath control, can aid in regulating emotions through its impact on the autonomic nervous system (ANS). It promotes emotional equilibrium by influencing physiological reactions linked to stress and anxiety. Engaging in pranayama stabilizes the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and mitigates the hyperactivity of the sympathetic nervous system, resulting in enhanced emotional regulation and increased mindfulness.14,15 The dysregulation of the ANS is believed to contribute to the emergence of dissociative disorders, typically characterized by disturbances in consciousness, memory, and identity. Engaging in pranayama facilitates activating the parasympathetic nervous system, thereby mitigating hyperarousal and fostering a tranquil state. This modulation of physiological stress responses can aid in reintegrating disjointed elements of consciousness, addressing the fundamental symptoms associated with dissociation.16–18

Research has demonstrated the therapeutic benefit of pranayama as a mind-body exercise.4,19–23 Significant improvement in stress and depression was found in a group of 50 female doctors who participated in a study to measure the effect of pranayama on stress in doctors.24 Controlled rhythmic yogic breathing has been reported as an effective complementary treatment for PTSD in military veterans.25 It has been reported that insomnia can be effectively managed through Bhramri pranayama.26 These studies indicate that pranayama might be a promising, innovative somatic intervention that can provide swift relief and serve as an adjunctive strategy to conventional therapeutic approaches for dissociative disorders.

According to the primary investigator’s (PI’s) own clinical experience at a district hospital in Sikkim, treating dissociative disorders has been a challenge, as caregivers often seek help from faith healers and approach health professionals only when the condition of the patient deteriorates.23 The PI has also observed that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) requires a minimum of 10 to 12 sessions, but most patients drop out after the first or second session. These observations led the PI to investigate if pranayama could be effective in managing the symptoms of dissociative disorders and providing fast relief among girls and women. There is a need for somatic therapy which provides fast relief and has an integrated approach. This work is a pioneering effort in that direction.

Patient Information

Patient 1. A 17-year-old female individual who was preparing for class 12 examination through open school presented with complaints of breathlessness, restlessness, chest pain, palpitation, insomnia, fainting spells, memory blanks, and headaches during the last four years. She was referred by the medical officer in the department of medicine to the department of psychiatry, as no evidence to explain her symptoms was found on physical examination, electroencephalogram (EEG), and biochemical blood analysis. Her attitude was cooperative and affect was anxious. She was second among three siblings. History revealed that for the last four years, she had experienced fainting spells and was unable to concentrate on her studies, and she had to drop out of school in class eight. After the death of her father in 2019 after long-term treatment for kidney failure, her condition deteriorated. Her mother found her often staring aimlessly, and she would not respond immediately when someone spoke to her. She often cut her hands with pieces of her glass bangles and would not remember how or when she cut her hands. She reported gaps in her memory and would sometimes hear the voice of a “black spirit” (kaala saya). The family also took her to a local faith healer who pronounced her to be under the influence of jinn and performed religious healing. There was no significant past history of any neurological or psychiatric disorder. Her developmental history was normal, and family relations were cordial. No history of substance abuse was noted. Issues of behavioral disturbance at school were reported.

Patient 2. A 26-year-old unmarried female individual visited the psychiatric outpatient department (OPD). Eight months before presentation to the OPD, she was diagnosed as having dissociative (conversion) disorder at a hospital in Gangtok, Sikkim. She was the eldest among three siblings and presented with complaints of breathlessness, fear, palpitation, sensitivity to sound, excessive thinking, deficit in attention and concentration, feeling numb and disconnected from her environment, and gaps related to recent memories. She experienced frequent panic attacks and insomnia. She worked as a laboratory technician in a diagnostics laboratory, and there was a marked decline in her work performance. For the last year, she reported a feeling of numbness and emptiness, and she also reported that she was unable to make a proper connection with anyone around her. At times, when stressed, she felt as if someone was calling her name and felt that someone was sleeping in her room. She heard voices that were not clear, which could suddenly trigger a panic attack. Her legs would shake, and her lips would quiver. Her developmental history was normal, and family relations were cordial. In 2016, she had gland tuberculosis, from which she fully recovered.

Patient 3. A 14-year-old female individual with a confirmed diagnosis of dissociative disorder presented to the psychiatric OPD. Three months prior to presentation, she was hospitalized at another hospital. She was the eldest of two children and presented with complaints of breathing difficulty, insomnia, and excessive thinking for the last year. Three months before presentation, she had her first dissociative experience; it lasted for 40 minutes, and she had no memory of it. She was found walking in her sleep. At home and school, she often stared aimlessly, and a marked decline in her class performance was reported. She reported that 3 to 4 times per week her mind became absolutely blank. There was a lack of attention and concentration in class. Prior to the onset of symptoms, she had performed well at school; after symptom onset, she could not do simple tasks at school, was confused, and had a lack of confidence and poor self-esteem. She reported that attending mathematics classes caused her panic and restlessness. Her attitude was cooperative and affect was anxious. There was no significant history of any neurological or psychiatric disorder. Her developmental history was normal, and family relations were cordial.

Clinical Findings

The physical and laboratory examinations performed at the hospital for all three cases were within the normal limit; therefore, they were referred to the psychiatric OPD. Dissociative disorders were diagnosed in the three cases following ICD-10 protocols,27 which reflects standard clinical practice in India; subsequently, consenting patients were evaluated with the Dissociative Experience Measure Oxford (DEMO) scale28 to establish baseline measurements before intervention.

All three patients reported difficulty breathing, restlessness, palpitations, panic, insomnia, excessive thinking, memory blanks, loss of appetite, and feeling numb and disconnected. Patients 1 and 2 heard voices and felt that someone was in their room. None of the three patients had a history of psychiatric disorders or substance abuse. For all three cases, the psychiatrist made a diagnosis of Dissociative Disorder, F44.0.27 Patients 1 and 2 were diagnosed as Dissociative Amnesia (F44.1) and Patients 3 was diagnosed as Dissociative Disorder Unspecified (F44.9).

A brief timeline of the occurrence of the first symptoms, diagnosis, commencement of the pranayama intervention, and follow-up is indicated in Table 1.

Diagnostic Assessment

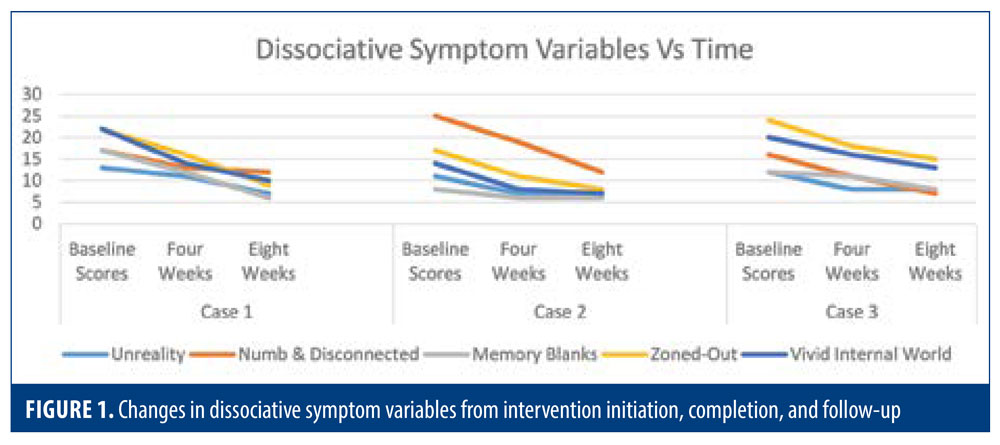

As dissociative disorders are psychiatric disorders, a symptom checklist was prepared using the DEMO scale.28 The scale contains 30 items rated on a five-point scale (1: not at all, 2: rarely, 3: sometimes, 4: often, 5: most of the time) and has five factors (unreality, numb and disconnected, memory blanks, zoned-out, vivid internal world). The scale was translated into Hindi. Pretests were done to document the baseline scores before the initiation of the intervention, and post-tests were conducted after the completion of the four weeks of intervention and after four weeks of follow-up.

Therapeutic Intervention

Signed informed consent was obtained from all three participants and caregivers before the initiation of the pranayama module, data collection, and use of their data for scientific reporting.

After receiving the ethical clearance from IEC New STNM Hospital, Gangtok (Memo no 03/IEC/STNM/22) to conduct this study and following informed consent, clinical history, and thorough psychiatric assessment, the three patients were administered a pranayama module. This unique module was designed by the PI, who is also a yoga teacher, for their physical and psychological state due to dissociative disorder (Table 2). The intervention included pranayama and meditation/relaxation techniques. Most of the pranayamas were sets of slow-breathing exercises to regulate parasympathetic activity. The practices were divided into morning and evening sessions and also included a different schedule for the menstrual cycle. Their progress was monitored daily, and all three patients reported relief and improvement in their symptoms. At the time of completion at four weeks, all three patients reported a remarkable improvement in their DEMO scores. Patients reported no adverse events during the four-week intervention or four-week follow-up.

During the study period, participants exclusively engaged in pranayama intervention, without any supplementary pharmacological or psychological therapies, to accurately evaluate the impact of pranayama on symptoms of dissociative disorder and eliminate potential confounding variables from other treatments.

Follow-up and Outcomes

At the completion of the four-week intervention, the three patients were followed up over the phone, and weekly online pranayama classes were organized for them for the next four weeks. Patients were motivated to continue their pranayama practice as a part of their daily routine and self-care. Dissociative symptom variables were assessed over the phone at the completion of the four-week follow-up. All patients reported a decline in symptoms and improvement in mood, sleep, appetite, and breathing. Patients and their caregivers reported good adherence to the daily pranayama practice.

The changes in the symptom score variables from the intervention initiation to completion at four weeks and follow-up is presented in Figure 1.

Discussion

A recent study from Sikkim, India, revealed that pranayama and meditation were found to be effective in managing symptoms of dissociative trance disorder in six female participants, indicating their potential as therapeutic approaches.29 This case series was an attempt to evaluate the effectiveness of pranayama in treating the symptoms of dissociative disorder among adolescents and women. It was noted that there was a marked improvement in all five variables related to the symptoms of dissociative disorder, as per the DEMO scale. Also, the three patients reported improvement in breathing, anxiety, excessive thinking, panic, insomnia, and hunger. There were no adverse events reported during the eight weeks of intervention and follow-up. As such, pranayama therapy can be considered as a safe monotherapy for the conventional management of mild and moderate cases of dissociative disorder.

The three patients also reported an improvement in depressed mood and psychic and somatic anxiety, which indicates that pranayama intervention, in addition to aiding in symptom management, might be effective in managing the psychological functioning of patients. The results are similar to a study that reported that six weeks of slow-breathing pranayama resulted in improvement in cognition, anxiety, and general wellbeing, as well as increased parasympathetic activity.30 Pranayama was found to be effective in controlling the stress of adolescents (12–17 years of age) at high schools in Mangalore.31 Another study suggested that the physiological functioning of adolescent girls improved with the practice of selected bandhas and pranayama.32 Additionally, a study on stress management for secondary school students in the 13 to 18 years age group suggested a soothing effect on stress levels. Pranayama and meditation were found to be easy, simple to follow, and economical, and no adverse effects were reported. This research emphasized the importance of implementing adequate yoga programs in schools.33

A study conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of Nadi Shodhana pranayama concluded that 75 percent of the participants reported improvements in feeling healthy, 80 percent reported improvements in memory recall, 75 percent reported improvements in mental stress relief, and 90 percent reported improvements in physical relaxation.34 Pranayama/alternate nasal breathing was found to significantly influence the parasympathetic nervous system in a study conducted in young adults.35 Yoga therapy, which included pranayama, was found to be effective in managing somatic complaints among employed women in Iran.36 In one study, practicing Hatha yoga with Omkar meditation for three months was found to increase the endogenous secretion of melatonin, which is responsible for improving sleep and overall wellbeing.37

Limitations. The main limitation of this study is the small sample size. The sample size of three is too small to understand the effect of pranayama clearly. Future research should focus on a larger sample size with a long-term follow-up and include a control group. Due to ethical considerations, all patients with dissociative disorders at the hospital are mandated to receive intervention, precluding the establishment of a control group without treatment, a decision that was sanctioned by the ethical clearance committee; furthermore, this case study functioned as a preliminary phase for a larger clinical trial.

Patient Perspectives

All patients found the pranayama intervention to be very helpful in managing their symptoms of dissociative disorder. All patients reported adherence to the daily paranayama schedule during follow-up. According to the first patient, “Pranayama exercises make me feel light, peaceful, and happy. Earlier, I had a loss of appetite, but now I can eat properly. I feel happiness in life, and the fearful thoughts and voices have disappeared. I have learned to control myself by controlling my emotions and excessive thinking. I wish to continue the practices in the future too.” The second patient said, “I no longer feel numb and disconnected, and my panic attacks have stopped. In fact, I had only one panic attack in the last two months. I feel safe and relaxed, and my partner has also started doing the pranayama exercises with me.” According to the third patient, who suffered from severe breathing problems and chest pain, “Pranayama exercises have signaled my body to return to the sense of calm. It helps me to sleep better and relaxes my mind. It has also helped me to calm down anxiety, emotional problems, etc. I would like to continue the practice and also recommend pranayama exercises to all those people who have health issues like me.”

Conclusion

The results of this preliminary case series are promising and indicate the feasibility of incorporating the pranayama intervention module as a monotherapy for the management of mild-to-moderate cases of dissociative disorders among girls and women. Such cases typically are referred to the emergency departments at the primary healthcare centers, and medical officers might have difficulty in managing such cases due to the psychosomatic nature of symptoms; this intervention can be implemented at primary healthcare centers, as well as government hospitals and schools.

References

- Spitzer C, Barnow S, Freyberger HJ, et al. Recent developments in the theory of dissociation. World Psychiatry. 2006;5(2):82–86.

- Cardeña E. The domain of dissociation. In: Lynn SJ, Rhue JW, eds. Dissociation: Clinical and Theoretical Perspective. The Guildford Press; 1994:15–31.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013:291–307.

- Varshney DKS, Agrawal M, Tripathi RK, et al. Pioneering approaches: navigating mind wandering and self-silencing in dissociated adolescent female sexual trauma survivors – an interpretative phenomenological analysis. Eur J Trauma Dissociation. 2024;8(4):100445.

- Fung HW, Lam SKK, Chien WT, et al. Dissociative symptoms among community health service users in Hong Kong: a longitudinal study of clinical course and consequences. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2023;14(2):2269695.

- Chiu CD, Meg Tseng MC, Chien YL, et al. Dissociative disorders in acute psychiatric inpatients in Taiwan. Psychiatry Res. 2017;250:285–290.

- Kim D, Kim D, Lee H, et al. Prevalence and clinical correlates of dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder at an outpatient trauma clinic in South Korea. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019;10(1):1657372.

- Kim I, Kim D, Jung HJ. Dissociative identity disorders in Korea: two recent cases. Psychiatry Investig. 2016;13(2):250–252.

- Kedare JS, Baliga SP, Kadiani AM. Clinical practice guidelines for assessment and management of dissociative disorders presenting as psychiatric emergencies. Indian J Psychiatry. 2023;65(2):186–195.

- Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s Synopsis of Psychiatry Behavioral Sciences/Clinical Psychiatry, 10th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins and Wolter Kluwer Health; 2007.

- Mascarenhas JJ, Krishna A, Pinto D, et al. Clinical patterns of dissociative disorder in in-patients from dakshina kannada district across two decades: a retrospective study in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Health Sci Res. 2019;(9):8:60–67.

- Chaturvedi SK, Desai G, Shaligram D. Dissociative disorders in a psychiatric institute in India–a selected review and patterns over a decade. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2010;56(5):533–539.

- Isaac M, Chand PK. Dissociative and conversion disorders: defining boundaries. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19(1):61–66.

- Betal C. Pranayama – a unique means of achieving emotional stability. Int J Health Sci Res. 2015;5(12):377–385.

- Jerath R, Crawford MW, Barnes VA, et al. Self-regulation of breathing as a primary treatment for anxiety. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2015;40(2):107–115.

- Beutler S, Mertens YL, Ladner L, et al. Trauma-related dissociation and the autonomic nervous system: a systematic literature review of psychophysiological correlates of dissociative experiencing in PTSD patients. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2022;13(2):2132599.

- Ginsberg JP. Editorial: dysregulation of autonomic cardiac control by traumatic stress and anxiety. Front Psychol. 2016;7:945.

- Owens AP, Low DA, Iodice V, et al. Emotion and the autonomic nervous system—a two-way street: insights from affective, autonomic and dissociative disorders. In: Stein J, ed. Reference Module in Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Psychology. Elsevier; 2017:923–928.

- Kelkar CD, Lekurwale PS, Kherde PR, et al. Effect of Bhastrika pranayama on “Shwasan Karma.” Int J Res Ayurveda Pharm. 2021;12(1):59–63.

- Sarkar C. Impact of pranayama on stress anger and quality of life for college students. Int J Phys Educ Sports Health. 2022;9(1):104–106.

- Satheesh R, Bindu CB. Pranayama improves cardio-respiratory efficiency and physical endurance in young healthy volunteers. Int J Res Med Sci. 2020;8(7):2421–2425.

- Telles S, Singh N, Balkrishna A. Role of respiration in mind-body practices: concepts from contemporary science and traditional yoga texts. Front Psychiatry. 2014;5:167.

- Varshney DK, Agrawal DM, Tripathi DR. Addressing dissociative trance disorder patients in India: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of adolescent girls’ help-seeking and encounters with inaccurate medical information. J Appl Res Child. 2022;13(2).

- Dilliraj G, Kannan H, Shanthi B. Effect of pranayama on stress in doctors. Int J Biomed Sci. 2020;40(1):102–104.

- Walker J, Pacik D. Controlled rhythmic yogic breathing as complementary treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans: a case series. Med Acupunct. 2017;29(4):232–238.

- Bhati KR, Bhalsing V, Manglekar A. Assessment of nidra as adharniya vega & its management with Bhramri pranayama. World J Pharm Res. 2018;7(3):1527–1541.

- World Health Organization. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders: clinical descriptions and diagnostic guidelines. World Health Organization Geneva; 1992:151–161.

- Černis E, Cooper M, Chan C. Developing a new measure of dissociation: The Dissociative Experiences Measure, Oxford (DEMO). Psychiatry Res. 2018;269:229–236.

- Varshney DK, Agrawal DM, Tripathi DR. Addressing dissociative trance disorder patients in india: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of adolescent girls’ help-seeking and encounters with inaccurate medical information. J Appl Res Child. 2022;13(2):1–34.

- Chandla SS, Sood S, Dogra R, et al. Effect of short-term practice of pranayamic breathing exercises on cognition, anxiety, general well being and heart rate variability. J Indian Med Assoc. 2013;111(10):662–665.

- Smitha KV. Effectiveness of pranayama for reducing stress among adolescents (12–17 years) of selected high schools at Mangalore. Int J Nurs Educ. 2020;8(4):497–500.

- Jayachitra M. Effect of pranayama and bandha practices on selected physiological variables among adolescent girls. Int J Phys Educ Sport Manag. 2012;1:10–17.

- Joshi K, Bohra S, Bora P, et al. A study of stress management on secondary students through pranayama and meditation. IJOYAS. 2020;9(1):41–44.

- Joshi A, Singh M, Singla BB, et al. Enhanced wellbeing amongst engineering students through nadi shodhana pranayama (alternate nostril breathing) training: an analysis. School Doc Stud (EU) J. 2011;(3):112–120.

- Sinha AN, Deepak D, Gusain VS. Assessment of the effects of pranayama/alternate nostril breathing on the parasympathetic nervous system in young adults. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(5):821–823.

- Behzadnia M, Ghasemian D, Ebrahimi S. Effectiveness of yoga therapy on somatic complaints of employed women in Iran. Int J Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;1(2):109–113.

- Harinath K, Malhotra AS, Pal K, et al. Effects of hatha yoga and omkar meditation on cardiorespiratory performance, psychologic profile, and melatonin secretion. J Altern Complement Med. 2004;10(2):261–268.