by Ben Onnink, MD; Matthew C. Correll, BS Candidate; Andrew Correll, BS, MD Candidate; and Terry Correll, DO

Dr. Onnink is a resident, Department of Psychiatry, Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine in Dayton, Ohio. Mr. M. Correll is a student at Wright State University Raj Soin School of Business in Dayton, Ohio. Mr. A. Correll is with Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine in Dayton, Ohio. Dr. T. Correll is Clinical Professor, Department of Psychiatry, Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine in Dayton, Ohio.

Funding: No funding was provided for this study.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2024;21(1–3):36–42.

Department Editor

Julie P. Gentile, MD, is Professor and Chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio.

Editor’s Note

The patient cases presented in Psychotherapy Rounds are composite cases written to illustrate certain diagnostic characteristics and to instruct on treatment techniques. The composite cases are not real patients in treatment. Any resemblance to a real patient is purely coincidental.

Abstract

Moral injury is a relatively new concept with varying definitions that attempts to define a profound and lasting insult to one’s conscience caused by perpetration of or directly witnessing harm to another person in a high-pressure situation. This entity is separate from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but it can coexist with PTSD. This article provides psychotherapeutic examples of the diagnosis of moral injury from a psychodynamic perspective, focusing on morally challenging situations related to warfare and the healthcare system.

Keywords: Moral injury, healthcare workers, psychotherapy, military trauma

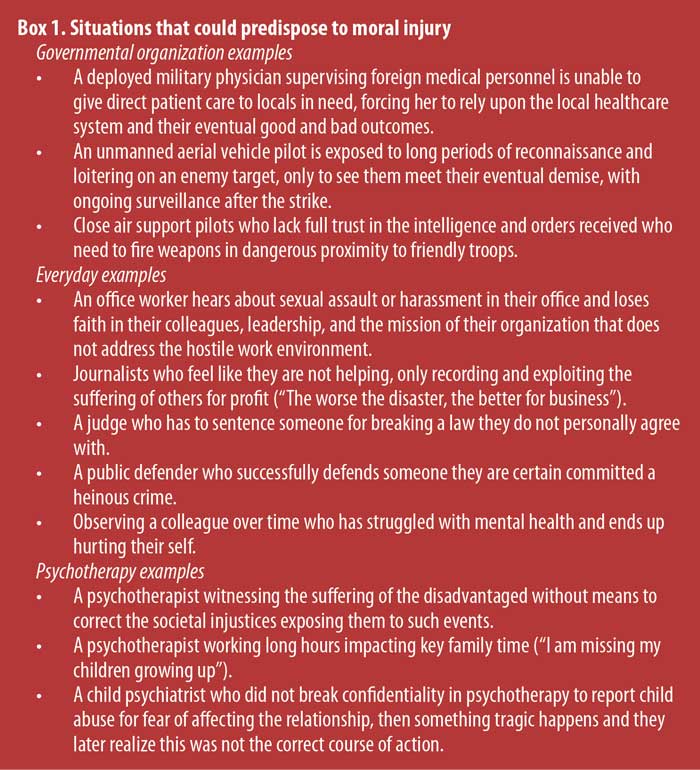

The term moral injury was originally coined by the psychiatrist Jonathan Shay in 1991 based on his work with Vietnam War veterans. He felt that the definition of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) published in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) did not adequately capture the psychopathology of the population he served, nor its deleterious effects. His proposed definition of moral injury is when there has been a betrayal of “what’s right,” either by a person in legitimate authority or by one’s self (“I did it”), in a high stakes situation.1 This was expounded on by Litz et al in 2009 to include acts of commission or omission by an individual.1,2 It should be noted that there are currently at least 12 different definitions of moral injury in the literature.3 Our simplified working definition, based primarily on the works of Drs. Shay and Litz, is that moral injury is a profound and lasting insult to one’s conscience caused by perpetration of or directly witnessing harm to another person in a high-pressure situation. Examples of situations that could lead to moral injury are given in Box 1.

Fictional Case Vignette 1

A 40-year-old male, A, presented for initial psychiatric evaluation, reporting that, “I’m just not feeling like myself anymore.”

Dialogue 1

Psychiatrist: We’ve already discussed the rules of engagement for psychotherapy, so could you please tell me what brings you into the office today?

A: I’ve been feeling down for the past few months. I have trouble sleeping, and I’m getting into more arguments at home with my wife.

Psychiatrist: Tell me more about how you have been feeling down.

A: Well, I used to like my life. I liked things such as going to work and hanging out with my kids, but I don’t find these things enjoyable anymore.

Psychiatrist: When did you first notice things feeling less enjoyable? Have your kids noticed a difference?

A: About half a year ago, I left the military and used my security clearance to get a job as an intelligence analyst with an agency reviewing footage from overseas warzones. My wife and kids have noticed a change in me, and that’s one of the reasons I’m getting help. It’s just hard to spend time with them since my job is very stressful, but I can’t talk much with them about what I do since most of it is classified.

Psychiatrist: How does this impact you?

A: I just lay in bed thinking in circles.

Psychiatrist: What kind of thoughts do you find yourself thinking about the most?

A: Basically, whether or not I’m a good person. (Begins crying) Like, my soul feels dirty, and it makes it hard to physically be in the same space as my family.

Psychiatrist: (Pauses and offers a tissue) I appreciate you sharing these feelings with me. Everyone can have moments of self-doubt and feeling like they don’t measure up. In as much detail as you are able to share, what makes you feel like your soul is dirty?

A: Well, I’m afraid if I tell you, you’ll have a negative opinion of me. Like, I don’t know your views on foreign policy, and I am afraid you won’t understand.

Psychiatrist: My job first and foremost is to be nonjudgmental and create a neutral and safe space with you. Please tell me more, as I want to understand your situation as best I can.

A: Okay, well, my job is to analyze video media obtained from human intelligence and aerial sources, and there are a lot of situations where innocent people have been killed. Even though I’m not pulling the trigger, I feel like being part of the process is wrong.

Practice Point 1: Barriers to Treatment

Establishing a frame, which the psychiatrist in the dialogue emphasized, creates a holding environment in which a patient can experience their own feelings and emotions.4 The psychiatrist gave the patient permission to set a limit on how in-depth their discussion would go. Psychotherapists should remain cautious to not encourage oversharing of traumatic experiences until a sufficient therapeutic alliance is formed. To do otherwise might be counterproductive and cause the patient to feel overwhelmed and potentially flee psychotherapy.

Multiple barriers to uncovering moral injury in a patient exist, including the patient’s concern that disclosing morally injurious events could lead to being shunned, rejected, or misunderstood.2 Patients might also fear that sharing could lead to adverse legal outcomes, especially if they acted as a perpetrator.5 The pervasive shame and guilt that coexist in moral injury can affect self-image (“I deserve to feel this way because of what I’ve done”), and patients might believe they are irredeemable and deserve to suffer.2 It is vital for psychotherapists to implicitly and explicitly foster a nonjudgmental and confidential space in order to bring forth full disclosure by the patient and work toward the goal of alleviating their suffering.

On the psychotherapist’s side, there might be unfamiliarity with the subject of moral injury, at least as compared to PTSD, which is in the DSM, fifth edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR). Psychotherapists might experience strong, negative countertransference toward patients, especially when hearing about morally questionable acts, such as killing civilians, particularly children. Overwhelming feelings of disgust, disdain, and revulsion toward the patient might appear, in addition to more subtle feelings of detachment. Psychotherapists might consciously or unconsciously feel that if they treat patients who have perpetrated morally questionable acts, it will excuse the behavior and thereby make them complicit.2 It can be helpful for psychotherapists to imagine the range of possibilities of violence that the patient might disclose; in doing so, they can anticipate revealing countertransferential reactions, which could lead a patient to only make a partial disclosure.2 It is also necessary listen to the patient’s narrative with empathy to best understand their perspective.

The patient began crying when he mentioned that he felt “dirty,” a word the psychiatrist initially repeats as a reflection. However, moving away from all-or-nothing language, such as clean or dirty, during psychotherapy may be helpful. Also, a psychodynamic approach might be helpful with the management of crying during psychotherapy. For example, one study of 64 psychotherapist and patient pairs with various therapeutic modalities showed that those with a psychodynamic approach had significantly higher levels of perceived compassion and support.6 The researchers also found that patients’ episodes of crying could lead to new, previously unknown self-discoveries. However, they also found that if the crying was followed by more negative feelings, such as tension and depression, then the therapeutic alliance was perceived as poor.6 We recommend that when clinicians encounter crying patients that they take a pause. This likely represents a unique opportunity to employ core empathy skills, such as listening, reflecting, and possible gentle probing, to support the patient, foster the therapeutic alliance, and potentially uncover new insights.

Clinical Pearls

- Helping patients realize the world is morally imperfect might alleviate psychological distress in their present situations.

- Keeping an open mind is important, as value judgments of moral injury by the clinician are fraught with difficulty.7 Belief systems are widely divergent and individualized, and the field of ethics is extremely complex and nuanced.

- Helping patients move away from all-or-nothing thinking can be beneficial.

- Seeking guidance from colleagues and/or supervisors could be wise if significant negative countertransference is developing within the therapeutic relationship.

Fictional Case Vignette 1, Continued

After several sessions, the psychiatrist and A had the following conversation:

Dialogue 2

Psychiatrist: One of the tests in your intake paperwork was the PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5), and you scored below the clinical cutoff of 33. Since you aren’t having other related symptoms, like nightmares or flashbacks, I don’t think you have PTSD.

A: But I feel like trash, Doc, and I just can’t get over what we’re doing at work.

Psychiatrist: Can you tell me more?

A: It feels like this one time in high school when I lied to my mom about where I went on a Friday night and did drugs with my friends. She never found out, but I felt like a totally awful person that was permanently stained.

Practice Point 2: Similarities and Differences Between Moral Injury and PTSD

Unidentified moral injuries are hypothesized to at least partly account for the observed lack of response of some patients to evidence-based psychotherapy for PTSD.8 Many strides have been taken in recent years to develop screening tools for moral injury, which now include the Moral Injury Symptom Scale-Military Version (MISS-M),9 the Brief Moral Injury Screen (BMIS),10 the Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES),11 and the Moral Injury Questionnaire-Military Version (MIQ-M).10 However, it is yet to be seen how these will be incorporated into practice, especially since moral injury is currently not a billable diagnosis or included in the DSM-5-TR or the World Health Organization’s International Statistical Classification of Diseases (WHO ICD).12

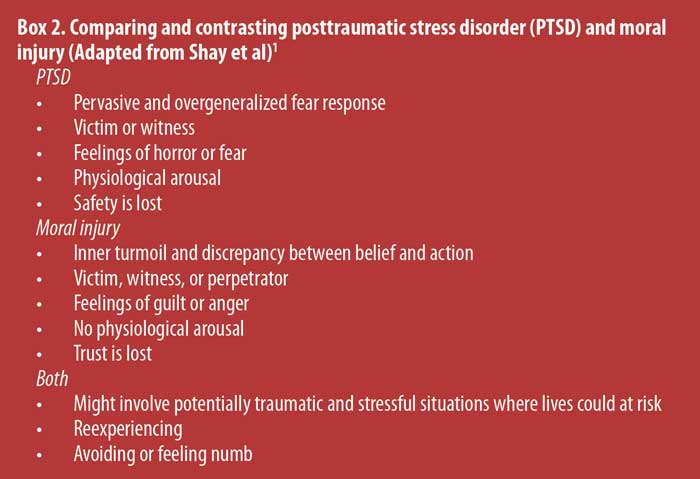

Unlike PTSD, which results from exposure to a traumatic experience involving interpersonal violence, moral injury stems from the violation of a person’s strongly held beliefs. Whereas PTSD is the product of a persistent and overgeneralized fear response, moral injury is an overwhelming cognitive dissonance between one’s self-image and their behaviors (Box 2). This leads to profound feelings of guilt and shame, which can cause social withdrawal.2,13 A perpetuating negative cycle could occur where someone with questions about morality might not be able to hear other’s opinions on the matter, which could otherwise facilitate cognitive restructuring and normalize the patient’s associated stress. Because the cognitive dissonance can reach existential levels, one is at risk for a complete loss of religious faith or spirituality.2,13 These two distinct entities, PTSD and moral injury, can coexist or occur independently. This was supported by Koenig et al9 in a multicenter study of Veteran’s Administration patients examining the association between MISS-M scores, PCL-5 scores, and existing PTSD diagnosis.

Practice Point 3: Risk Factors for Moral Injury

Despite mental preparation and behavioral conditioning, even legal and justified killing of enemy combatants in war can leave many people with lingering uncertainty. This uncertainty can go on to erode their sense of purpose and meaning. While moral injury is not exclusive to military personnel, it is the most-studied population in regard to this condition, and the following identified risk factors have been derived from that population. In a review article written by the psychiatrists Koenig and Al-Zaben,14 younger age, White race, lower education, poor social support, lower religiosity, combat exposure, multiple deployments, physical disability or chronic pain, and substance abuse were identified as risk factors for the development of moral injury. A study of 1,032 veterans in a private hospital system in Pennsylvania revealed that neuroticism, antisocial traits, low self-esteem, low unit morale, high anomie (lack of the usual social or ethical standards in an individual or group), high fear of death, and in-service concussion were significantly associated with elevated MIES scores.15 “Black-and-white” thinking and a predisposition for feeling shame are further hypothesized risk factors.2

There is evidence in the veteran population that religious or spiritual beliefs serve as a protective factor against the development of moral injury.9 Exposure to explicit stimuli might polarize moral attitudes, as in one study where exposure to emotionally charged images of abortion increased the strength of moral conviction in participants.16 There is also evidence that moral injury seems to co-occur with depressive psychopathology.17,18 Those with moral injury who are predisposed to depression are more likely to show symptoms relating to depression rather than symptoms relating to anxiety. In one study, civilian deaths or disproportionate violence were the most likely events to present with signs and symptoms of moral injury.19

Fictional Case Vignette 2

A 44-year-old female healthcare worker (HCW) presented for an initial psychiatric evaluation with a chief complaint of burnout.

Dialogue 3

Psychiatrist: What brings you in today?

HCW: I feel sad.

Psychiatrist: Sad? What do you think is causing you to feel this way?

HCW: I feel like this work that I’m doing is totally meaningless.

Psychiatrist: Meaningless? But I read on your intake paperwork you’re a critical care physician. I imagine that you help many people in need every day.

HCW: I am a doctor, but I am only one person, and particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic, when 10 out of 10 ventilators were being used and reserve nurses were working full-time hours, I wasn’t able to double check that my patients were getting the treatment they deserved. I chose to go into critical care because I wanted to be in control. But now it seems that the needs are exceeding the resources.

Psychiatrist: So, what you are saying is that your team is basically at or beyond their limit?

HCW: Yes, and now I’m realizing that I am steering a ship that is potentially shortening lives. They might be better off not coming to a hospital where they receive substandard care.

Psychiatrist: It sounds hard to be in a position of responsibility but unable to enact change. Have there been any specific bad outcomes that have impacted you?

HCW: Last week, I was unable to check all of my patients’ heparin drips before leaving like I usually do. I was just really stressed and wanted to go home to see my kids. I hoped my team would take care of things, but a new nurse who was probably overwhelmed didn’t round frequently overnight and missed a patient’s leg becoming swollen with polka dot bruises everywhere.

Psychiatrist: What happened?

HCW: Classic heparin-induced thrombocytopenia, which usually shows up five days after starting a heparin drip. Before long, we had to consult surgery and they removed his leg, which was becoming necrotic. How can I work in a system that only sees bottom lines and isn’t conducive to provide the adequate number of staff that is needed for quality care?

Practice Point 4: Moral Injury in Different Career Fields

As the psychiatrist did in this scenario, leading with an open-ended question is wise. Oftentimes, more multifaceted emotions/cognitions lie underneath statements like “I feel sad.” It is the privilege of the psychotherapist to help unpack such statements. One way to do this is by pointing out apparent contradictions, like the juxtaposition of “critical care physician” and “meaningless.” High-risk disease outbreaks, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, can cause HCWs to become aware of such contradictions, as they risk their own lives while taking care of patients. HCWs had to deal with heightened work demands and a lack of adequate resources, including time and ventilators, during periods when infection rates were on the rise. Additionally, they had to grapple with concerns about contracting the virus and potentially transmitting it to their loved ones.20

Most research on moral injury in HCWs so far has been descriptive and cross-sectional, describing ethical suffering where external constraints caused healthcare personnel to prioritize tasks over human dignity.21 Societal inequalities based on wealth, race, and demographics that influence the healthcare a psychiatrist provides can be morally injurious. Healthcare systems that tend to focus on market-driven priorities might also predispose to moral injury.22 Healthcare organizations might emphasize tertiary care (specialized care delivered in a hospital) because of greater reimbursement over primary prevention medicine.23

With the healthcare sector being a significant portion of the economy in the United States (US), there are unique economic, legal, and institutional pressures that can guide patient care in ways that may or may not be aligned with caregivers’ personal values.24 Psychologically, moral injury can manifest as cynicism and loss of joy for the parts of medicine that someone used to find meaningful. Some have called these ongoing thoughts and feelings after a precipitating event a type of “moral residue.”22 Examples in providers include where there is pressure to prescribe medications, such as benzodiazepines (psychiatrists account for only 16% of benzodiazepine prescriptions25), that increase patient satisfaction scores and reimbursement rates. In this situation, the physician could feel like a perpetrator in giving patients what they want in the short-term, but with significant risk of potential long-term damage.

Clinical Pearls

- If a HCW is being evaluated for burnout, think about screening for moral injury, given the predisposing economic and societal pressures.

- If someone says a simple but loaded statement (“I feel sad”), understand that they might be unaware of underlying feelings (e.g., shame, embarrassment, distrust).

- A feeling of powerlessness is a common theme in discussions surrounding moral injury, so helping shift a patient’s perspective from a predominantly external to internal locus of control could be beneficial.

- If someone feels at their limit, potentially explore what this limit implies. Are they at the limit of their coping mechanisms with the stress they are experiencing? If so, this could be a chance to suggest powerful healthy lifestyle interventions, such as healthy diet, exercise, good sleep hygiene, healthy stress management and coping, social connections, and avoidance of risky substances.26

- In general, it is preferable to allow the patient to take the lead and talk more than the psychotherapist.

Fictional Case Vignette 2, Continued

Dialogue 4

Psychiatrist: Can you tell me a little about what it was like growing up?

HCW: Well, my parents were super strict. They expected me to be the perfect child. But I don’t see what any of that has to do with my current situation.

Psychiatrist: Even though we usually are not thinking about our childhood in everyday life, almost all of what we do and think has at least some foundation from that period in our lives.

HCW: Huh. I didn’t know that. I always thought that was a cliché.

Psychiatrist: Does your current situation feel at all like how it was growing up?

HCW: Yeah, a little. It’s like my mind is constantly criticizing me just like my parents used to. It’s always been like this to a degree, and it’s probably what makes me a good doctor.

Practice Point 5: Psychodynamic Underpinnings of Moral Injury

What causes someone to develop a moral framework with a predisposition for moral injury? A person’s moral architecture is derived from their unique childhood and adolescent experiences27 and genetics, likely to a lesser degree.28 While there is currently not enough evidence to develop a model, it is clear that cognitive rigidity plays a large role in the ruminative cycle of moral injury. We hypothesize an underlying hyperdeveloped, oppressive, and harsh29 superego might lead to cognitively-impaired abilities to appreciate broader external/contextual factors surrounding morally questionable acts of commission or omission.

First, we will look to the neurologist and psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud for his structural model of the id, ego, superego, and psychosexual stages of development. Heinz Hartman, a psychiatrist and pupil of Freud, expanded on these concepts by proposing that during childhood, one develops their moral standards (represented by the superego) in order to temper their selfish drives (represented by the id) to remain under the protection and good grace of their primary attachment figures (or else risk death). This stage, known as the phallic stage in Freud’s overarching drive theory, occurs between the ages of three and six years.30 This corresponds to the stage of initiative versus guilt developed as part of psychoanalyst Erik Erikson’s psychosocial stages of development. During the initiative versus guilt stage, children develop the ability to either initiate tasks or feel guilty and paralyzed, unable to initiate them. People learn to develop initiative, learn from mistakes, build self-confidence, and mitigate guilt if they successfully navigate this stage.31

Erikson proposed that a child’s initiative and superego are closely related. For instance, if caregivers excessively enforce strict or punitive discipline, this can give rise to a guilt-prone superego and foster self-criticism, diminishing the child’s willingness to explore new endeavors and constraining their range of experiences.32 If individuals developed a propensity toward guilt at a young age, it could make them more susceptible to moral injury in the future. On the other hand, if caregivers fail to encourage curiosity and initiative at all, there can be a propensity toward paralyzing ambivalence, therefore increasing the risk of moral injury developing later in life through acts of omission. Understanding these formative experiences can provide a potential avenue for treatment.

Therefore, the period between the ages of three and six years is critical for moral development, as represented by the superego. While a hyperdeveloped superego can be beneficial in normal life due to conscientiousness,33 if a morally injurious event occurs, the superego could cause one to re-experience feelings of childhood guilt. Their superego could cause this through cognitive distortions, including a lack of appreciation of the unique context and contingencies of the morally questionable act and severe condemnation.2 Rather than trying to fight a hyperdeveloped superego, which would likely leave both parties frustrated, psychotherapists should adopt the strategy of having the patient truly appreciate the full context of their actions and accept an imperfect self.2

The psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg created the best-known model of moral reasoning (morality), divided into three sequential levels: pre-conventional, conventional, and post-conventional morality (Figure 1).27 With each successive stage, morality becomes increasingly abstract and mature. Individuals operating with pre-conventional, immature morality are focused on personal gain34 and are therefore unlikely to experience moral conflict. Individuals operating with conventional morality are generally interested in “fitting in” with society.34 This system of morality can predispose them to moral injury due to personal interpretations of morally questionable acts that contrast with societal norms. In their article on moral injury, Molendijk et al35 included a poignant illustration of conventional morality from the documentary Beer is Cheaper than Therapy: “I’m 22 years old, and I must have killed 30 people. The same thing that you were given badges for over in Iraq, you would be considered a serial killer over here. That’s a very weird thought to have running around in your head when it’s dark, going to sleep, or late at night.”35

Individuals who have attained post-conventional morality seek to resolve moral challenges not by reference to established societal rules, but in terms of general principles of justice, fairness, and social utility.36 A post-conventional cognitive framework is common among HCWs,37 who are at risk for developing moral injury if their individual conscience clashes with the goals of the organization. Universal moral ideas about how everyone should act would necessarily extend to the organization they are with and create dissonance if their actions differ.

Clinical Pearls

- If someone is hesitant to talk about their childhood due to preconceived notions (e.g., “It is all psychobabble”), take a moment to explain how childhood shapes us as adults.

- If someone continues to be reluctant to discuss their childhood in psychotherapy, resist the urge to push them, while noting possible trauma or unresolved conflict.

- It is important to consider a patient’s psychodynamic background in relation to Kohlberg’s stages of moral development to better understand the patient and evaluate their susceptibility to moral injury.

Conclusion

Moral injury is an emerging idea seeking to describe a deep and profound insult to one’s conscience caused by perpetration of or directly witnessing harm to another person in a high-pressure situation. This article explored fictional case studies of moral injury from a psychodynamic approach, highlighting ethical challenges encountered in military conflict and medical settings. Due to the paucity of research on moral injury, in association with and separate from PTSD, more investigation into this area would be helpful.

References

- Shay J. Moral injury. Psychoanal Psychol. 2014;31(2):182–191.

- Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695–706.

- Denov M. Encountering children and child soldiers during military deployments: the impact and implications for moral injury. Eur J Psychotraumatology. 2022;13(2):2104007.

- Gray A. An Introduction to the Therapeutic Frame. Routledge; 2013.

- Williamson V, Murphy D, Stevelink SAM, et al. Confidentiality and psychological treatment of moral injury: the elephant in the room. BMJ Mil Health. 2021;167(6):451–453.

- Zingaretti P, Genova F, Gazzillo F, Lingiardi V. Patients’ crying experiences in psychotherapy: relationship with the patient level of personality organization, clinician approach, and therapeutic alliance. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2017;54(2):159–166.

- Farnsworth JK. Is and ought: descriptive and prescriptive cognitions in military-related moral injury. J Trauma Stress. 2019;32(3):373–381.

- Vermetten E, Jetly R. A critical outlook on combat-related PTSD: review and case reports of guilt and shame as drivers for moral injury. Mil Behav Health. 2018;6(2):156–164.

- Koenig HG, Ames D, Youssef NA, et al. The Moral Injury Symptom Scale-Military Version. J Relig Health. 2018;57(1):249–265.

- Nieuwsma JA, Brancu M, Wortmann J, et al. Screening for moral injury and comparatively evaluating moral injury measures in relation to mental illness symptomatology and diagnosis. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2021;28(1):239–250.

- Nash WP, Marino Carper TL, Mills MA, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the Moral Injury Events Scale. Mil Med. 2013;178(6):646–652.

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD). 2022. https://icd.who.int/browse/2024-01/mms/en. Accessed 16 Feb 2024.

- Frankfurt SB, Frazier P, Engdahl B. Indirect relations between transgressive acts and general combat exposure and moral injury. Mil Med. 2017;182(11):e1950–e1956.

- Koenig HG, Al Zaben F. Moral injury: an increasingly recognized and widespread syndrome. J Relig Health. 2021;60(5):2989–3011.

- Boscarino JA, Adams RE, Wingate TJ, et al. Impact and risk of moral injury among deployed veterans: implications for veterans and mental health. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:899084.

- Wisneski DC, Skitka LJ. Moralization through moral shock: exploring emotional antecedents to moral conviction. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2017;43(2):139–150.

- Nickerson A, Hoffman J, Schick M, et al. A longitudinal investigation of moral injury appraisals amongst treatment-seeking refugees. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:667.

- Hall NA, Everson AT, Billingsley MR, Miller MB. Moral injury, mental health and behavioural health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2022;29(1):92–110.

- Vargas AF, Hanson T, Kraus D, et al. Moral injury themes in combat veterans’ narrative responses from the National Vietnam Veterans’ Readjustment Study. Traumatology. 2013;19(3):243–250.

- Riedel PL, Kreh A, Kulcar V, et al. A scoping review of moral stressors, moral distress and moral injury in healthcare workers during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3):1666.

- Čartolovni A, Stolt M, Scott PA, Suhonen R. Moral injury in healthcare professionals: a scoping review and discussion. Nurs Ethics. 2021;28(5):590–602.

- Sales PMG, Arshed A, Cosmo C, et al. Burnout and moral injury among consultation-liaison psychiatry trainees. Psychodyn Psychiatry. 2021;49(4):543–561.

- Cummings S, Parham ES, Strain GW. Position of the American Dietetic Association: weight management. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102(8):1145–1155.

- Rosen A, Cahill JM, Dugdale LS. Moral injury in health care: identification and repair in the COVID-19 era. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(14):3739–3743.

- Cascade E, Kalali AH. Use of benzodiazepines in the treatment of anxiety. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2008;5(9):21–22.

- Merlo G, Vela A. Mental health in lifestyle medicine: a call to action. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2022;16(1):7–20.

- Kohlberg L, Hersh RH. Moral development: a review of the theory. Theory Pract. 1977;16(2):53–59.

- Vertsberger D, Abramson L, Knafo-Noam A. The Longitudinal Israeli Study of Twins (LIST) reaches adolescence: genetic and environmental pathways to social, personality and moral development. Twin Res Hum Genet. 2019;22(6):567–571.

- Lesley M. Psychoanalytic perspectives on moral injury in nurses on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2021;27(1):72–76.

- Bienenfeld D. Psychodynamic Theory for Clinicians. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006.

- Erikson EH. Childhood and Society. Norton; 1993.

- Lambert MC, Kelley HM. Initiative versus guilt. In: Goldstein S, Naglieri JA, eds. Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development. Springer US; 2011:816–817.

- Hogan J, Ones DS. Chapter 32 – Conscientiousness and integrity at work. In: Hogan R, Johnson J, Briggs S, eds. Handbook of Personality Psychology. Academic Press; 1997:849–870.

- Yilmaz O, Bahçekapili HG, Sevi B. Theory of moral development. In: Shackelford TK, Weekes-Shackelford VA, eds. Encyclopedia of Evolutionary Psychological Science. Springer International Publishing; 2021:8148-8152. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-19650-3_171

- Molendijk T, Kramer EH, Verweij D. Moral aspects of “moral injury”: analyzing conceptualizations on the role of morality in military trauma. J Mil Ethics. 2018;17(1):36–53.

- Emler N, Tarry H, St. James A. Post-conventional moral reasoning and reputation. J Res Personal. 2007;41(1):76–89.

- Jean-Tron MG, Ávila-Montiel D, Márquez-González H, et al. Differences in moral reasoning among medical graduates, graduates with other degrees, and nonprofessional adults. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22:568.

- Crain WC. Kohlberg’s stages of moral development. In: Theories of Development: Concepts and Applications, 2nd edition. Prentice-Hall, Inc.; 1985:118–136.