by Riwaj Bhagat, MD, and Martin Brown, MD

by Riwaj Bhagat, MD, and Martin Brown, MD

Dr. Bhagat and Dr. Brown are with the University of Louisville, Department of Neurology in Louisville, Kentucky.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this study.

DISCLOSURES: The author has no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

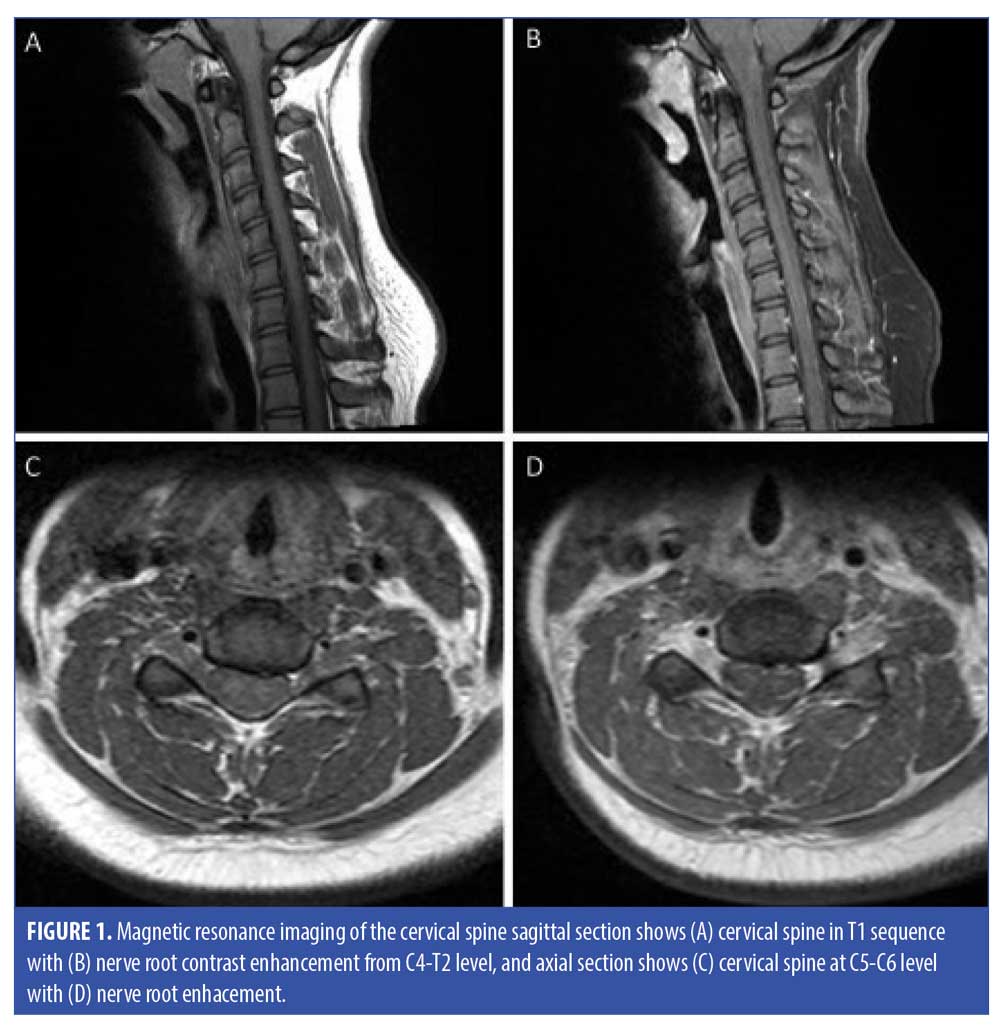

ABSTRACT: Anti-ganglioside D1b (GD1b) Immunoglobulin G (IgG) positive Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) is rare and usually presents with acute sensory or cerebellar ataxia, ascending paralysis, and loss of deep tendon reflexes (DTRs). A 19-year-old female individual with recent Influenza A infection had an acute onset of facial diplegia and minimal leg weakness with preserved DTRs. Cerebrospinal fluid analysis showed albuminocytologic dissociation with positive serum anti-GD1b IgG antibody (52 IV; reference range 0–50). Magnetic resonance imaging of the cervical spine showed nerve root enhancement. Following intravenous immunoglobulin therapy and subsequent physiotherapy, the patient reached the nadir of leg weakness by one month and had complete motor recovery after one year. Sensory ataxia was observed in the fourth month of the illness, which subsided by eight months. DTRs were normal throughout the course of the disease. This case showed an unusual evolution of GBS with a positive anti-GD1b antibody presenting with acute facial diplegia, normal DTR and delayed sensory ataxia.

Keywords: Facial diplegia, GBS, GD1b antibody

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2021;18(7–9):18-20

Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) has multiple variants, which are distinguished by clinical features, serum antibodies, and nerve conduction studies.1 GBS with positive serum anti-ganglioside D1b (GD1b) antibody (Ab) is rare and commonly presents with acute ascending weakness, areflexia, sensory disturbances, and cerebellar signs.2–6 Common serum anti-ganglioside antibodies (Abs) seen in the acute demyelinating GBS variant include anti- GT1b Ab, whereas axonal variants can be associated with anti- GM1 and anti-GM2 Abs.7 Anti-GD1b Ab positive serum is less common (around 10%) in patients with GBS and anti-ganglioside Abs positive sera.8

Case Description

A 19-year-old healthy female patient who had recently contracted influenza A had an acute onset of facial weakness, speech disorders, drool, fatigue, and tingling sensation in all four extremities that started a week prior to the presentation and have persisted since. The patient denied any inducing event or new medication, recent travel, bites from insects or animals, ingestion, inhalation, or exposure to known toxic substances.

On examination, she had bilateral facial nerve paralysis, decreased taste in two-thirds of her tongue, right eye hypertropia without diplopia, horizontal nystagmus, dysarthria, 5/5 modified Rankin scale (mRs) motor strength in proximal and distal upper extremities, 5/5 mRs and 4/5 mRs motor strength in proximal and distal lower extremities respectively, and orthostatic hypotension. Deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) were preserved with intact cerebellar, sensory, bowel, and bladder functions. Acute facial diplegia and motor weakness had board inflammatory, infectious, and metabolic differential diagnosis like Lyme disease, syphilis, viral infection, GBS, sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and others, which prompted extensive investigations for specific etiology.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis had shown an albuminocytologic dissociation with the protein of 189mg/dL and total nucleated cells of two, which was suggestive of acute inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy or GBS. Given atypical presentation of GBS with preserved DTRs, specific serum anti-gangliosides antibodies were tested which showed positive anti-GD1b IgG Ab of 52 IV (reference range: 0–50; ARUP labs) and negative anti-GD1b IgM Ab of 14 IV. The remaining serum-specific anti-gangliosides Abs tested negative including anti-IgG/IgM GM1 and anti-GQ1b IgG/IgM.

The patient had a low titer (1:80) of serum anti-nuclear antibody (ANA). Furthermore, ANA specific Abs including anti-DNA Abs, smith/ribonucleoprotein Abs, anti-scleroderma-70 Abs, Sjogren’s Abs, anti-Centromere Abs, anti-myeloperoxidase Abs, anti-proteinase 3 Abs, and cytoplasmic/perinuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies were negative. Serum angiotensin converting enzyme was also negative. Metabolic workup including thyroid hormone, serum copper, vitamin E, vitamin B12, vitamin B6, and creatine kinase concentrations were all within normal limits. Serology for infectious etiologies, which included Lyme disease, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), syphilis, herpes simplex virus, Epstein Barr virus, and hepatitis, were negative. Regarding radiological workup, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was unremarkable. MRI of the cervical spine showed nerve root enhancement extending from C4 to T2 level (Figure 1).

The patient was diagnosed of GBS and was treated with intravenous immune globulins (IVIG) at a dose of 2gm/kg body weight divided over three days. After the treatment, there was minimal improvement in facial expression, but the tingling sensation and weakness of the lower limbs persisted. Considering the weakness, Hughes GBS disability score (DS) ranging from 0 to 6 (0: normal, 1: minor symptoms or signs but able to run, 2: able to walk 5 meters independently, 3: able to walk 5 meters with help, 4: bed or chair-bound, 5: requiring assisted ventilation, and 6: death) was used as a functional prognostic score for accessing disease progression.9 At the time of discharge, the patient was able to walk unassisted (GBS DS 2). The patient received outpatient physical therapy (PT) and gabapentin for nerve pain. The patient denied getting nerve conduction studies despite of risk and benefit discussion.

At the end of four weeks, bilateral facial paralysis, hypertropia of the right eye and dysarthria resolved, but the leg weakness worsened. She was not capable of standing or walking even with assistance (GBS DS 4). Her DTRs remained intact. After the fourth week, she gradually improved the strength of the lower limbs without any treatment other than physiotherapy. By Week 16, she could stand and walk with help (GBS DS 3), but she developed a new onset of sensory ataxia with reduced proprioception and vibratory sensation in the distal lower extremities. DTRs were still normal. She continued receiving physiotherapy and, after 32 weeks, her sensory deficits were resolved, and she was able to walk unassisted (GBS DS 2). At the end of 48 weeks, she was able to run, had minimal paresthesia on her thigh (GBS DS 1) and was independent in her daily activities.

Discussion

GBS is an autoimmune demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy where Abs are often produced against ganglioside of the myelin sheath covering peripheral nerves. It is believed that these autoantibodies are produced from molecular mimicry mechanism in which Abs produced against antecedent infection cross-reacts with peripheral nerve components that share cross-reactive epitopes.1 Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (AIDP) is the most common variant of GBS that traditionally presents itself as ascending motor weakness, loss of deep tendon reflexes with/without the involvement of cranial nerves. Other less common phenotypic variants include Miller Fisher Syndrome, pharyngo-cervical-brachial pattern, pure sensory variant, and pure motor variant.1 Influenza vaccine and infection exposures are seldom associated with GBS.10,11 To date, a single case of GBS with anti-GD1b antibody after influenza A infection has been reported who presented with tetraparesis, areflexia, sensory ataxia, and pan-sensory loss.4

Our patient principal characteristics were acute facial diplegia with preserved DTRs. Hypo/areflexia is one of the clinical diagnostic criteria for GBS, whose absence decreases its diagnostic accuracy.1,12 As in our patient, acute facial diplegia with preserved DTRs might be mistaken for other differentials like Lyme disease, sarcoidosis, bilateral Bell’s palsy, meningitis (paraneoplastic or infectious), multiple idiopathic cranial neuropathies, brain stem encephalitis, benign intracranial hypertension, leukemia, HIV, syphilis, and vasculitis.13 Another atypical feature of our patient was a delayed onset of sensory ataxia and absence of cerebellar signs that have been observed early in other patients with GBS and positive anti-GD1b Ab.3–6

Typically, the nadir of weakness in GBS reaches within 4 to 6 weeks, following which recovery is complete or incomplete overtime.1,12 If there is continued progression or return of any symptoms (a relapse) after six weeks, the diagnosis of GBS is no longer appropriate. In this scenario, additional treatment by repeating IVIG or plasmapheresis might be considered.1 GBS DS could be a valuable marker for accessing the clinical progression and management of classical, limb-onset GBS. As in this case, the patient’s GBS DS improved after four weeks without the need for an additional IVIG.

Conclusion

This case describes an unusual clinical course of a rare serological variant of GBS preceded by influenza A infection. The GBS associated with anti-GD1b IgG Ab might have acute facial diplegia and normal DTRs, whereas sensory ataxia might occur later. These cases should be identified and treated quickly for a good prognosis.

References

- Willison HJ, Jacobs BC, van Doorn PA: Guillain-Barre syndrome. Lancet.

2016;388:717–727. - Kaida K, Kamakura K, Ogawa G, et al. GD1b-specific antibody induces ataxia in Guillain-Barre syndrome. Neurology. 2008;71:196–201.

- Pan CL, Yuki N, Koga M, et al. Acute sensory ataxic neuropathy associated with monospecific anti-GD1b IgG antibody. Neurology. 2001;57:1316–1318.

- Simpson BS, Rajabally YA. Sensori-motor Guillain-Barre syndrome with anti-GD1b antibodies following influenza A infection. Eur J Neurol. 2009;16:e81.

- Sugimoto H, Wakata N, Kishi M, et al. A case of Guillain-Barre syndrome associated with cerebellar ataxia and positive serum anti-GD1b IgG antibody. J Neurol. 2002;249:

346–347. - Yuki N, Susuki K, Hirata K: Ataxic form of Guillain-Barr syndrome associated with anti-GD1b IgG antibody. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;69:136–137.

- Naik GS, Meena AK, Reddy BAK, et al. Anti-ganglioside antibodies profile in Guillain-Barre syndrome: correlation with clinical features, electrophysiological pattern, and outcome. Neurol India. 2017;65:1001–1005.

- Kusunoki S. Antiglycolipid antibodies in Guillain-Barre syndrome and autoimmune neuropathies. Am J Med Sci.

2000;319:234–239. - Hughes RA, Brassington R, Gunn AA, van Doorn PA. Corticosteroids for Guillain-Barré syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:Cd001446.

- Juurlink DN, Stukel TA, Kwong J,et al. Guillain-Barre syndrome after influenza vaccination in adults: a population-based study. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:

2217–2221. - Lehmann HC, Hartung HP, Kieseier BC, Hughes RA. Guillain-Barre syndrome after exposure to influenza virus. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10:643–651.

- Asbury AK, Cornblath DR: Assessment of current diagnostic criteria for Guillain-Barre syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1990;(27 Suppl):S21–S24.

- Keane JR: Bilateral seventh nerve palsy: analysis of 43 cases and review of the literature. Neurology.1994;44:1198–1202.