by Jessica A. Porcelan, MD; Katherine E. Caujolle-Alls, MD; and Julie P. Gentile, MD

by Jessica A. Porcelan, MD; Katherine E. Caujolle-Alls, MD; and Julie P. Gentile, MD

Drs. Porcelan, Caujolle-Alls, and Gentile are with the Department of Psychiatry at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio.

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Department editor

Allison E. Cowan, MD, is an associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio.

Editor’s Note

The patient cases presented in Psychotherapy Rounds are composite cases written to illustrate certain diagnostic characteristics and to instruct on treatment techniques. The composite cases are not real patients in treatment. Any resemblance to a real patient is purely coincidental.

Abstract: Individuals with intellectual disability (ID) and traumatic brain injury experience mental health issues at a higher rate than the general population. They are typically more vulnerable to stress, have fewer coping skills, and possess a smaller system of natural supports. It is clear that level of intelligence is not the sole indicator of the appropriateness of psychotherapy and that the full range of mental health services are able to help improve the quality of life for patients with intellectual disability. Special issues related to motivational interviewing, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), and supportive psychotherapy are described with specific attention to special issues for the intellectual disability population and effective adaptations addressed.

Keywords: intellectual disability, traumatic brain injury, developmental disability, psychotherapy in intellectual disability, motivational interviewing in intellectual disability, cognitive behavioral therapy in intellectual disability, supportive psychotherapy in intellectual disability

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2019;16(11–12):14–18

Psychotherapy is an evidence-based practice with proven efficacy in the intellectual disability (ID) patient population.1,2 Much work has been done in recent years to disprove the myth regarding the lack of efficacy of mental health treatment within the ID patient population; informed clinicians are cognizant of the fact that psychotherapy is, in fact, a best practice when working with patients with ID.3,4 Especially when provided with the right resources, patients with ID can grow, change, and recover from mental illness.5,6 The amount of research on this subject has grown considerably over the last 10 years, and there also has been an increase in the amount of training opportunities available for clinicians.7,8 That said, while there has been much progress made in a relatively short period of time, there is still more work to be done, since this remains a significantly underserved population.9,5

The extent of currently available literature is variable depending on the type of therapy being evaluated. While there are limited studies on the topic, supportive psychotherapy has been shown to improve communication and decrease severity of regression after 6 to 18 months.10 There is less available research that specifically evaluates motivational interviewing in the ID population; after constructing semistructured qualitative interviews and focus groups, one study recommended several modifications to include adjustments for both language level and cognitive level to achieve maximum effectiveness.11 Interestingly, this study also suggested that traits of the therapist, such as empathy, honesty, and trustworthiness, were critical for effective motivational interviewing.11

Not surprisingly, more studies exist for the commonly utilized cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). One recent systematic review found the most common modifications to CBT included the Hurley adaptation categories of simplification, activities, and inclusion of caregivers;12 a smaller prior study that also incorporated the Hurley framework noted similar findings but also displayed a higher adaptation in the category of “flexible methods,” which includes flexibility in both structure and adherence to a specific therapeutic approach.6 Another review found that the majority of studies evaluated had statistically significant improvements in at least half of the outcome measures used and concluded that CBT has a positive evidence base for treating patients with ID and comorbid mental health diagnoses13. Additionally, studies suggest that patients report positive feelings about CBT; one study identified three overarching positive themes identified by patients with ID, which were talking in therapy, feeling valued and validated, and change in therapy, respectively.13,14 This literature review illuminates the need for further research in this area.

Overall, there exist limited studies regarding therapy modalities within the ID population, despite evidence that these patients do benefit from psychotherapy. However, the research that does exist has demonstrated the need to adjust the mode of therapy provided to fit the developmental level, dependence needs, and verbal/cognitive abilities of each individual patient receiving treatment.6,15 This requires clinicians to be flexible in their approach and adapt interventions to accommodate for differences in intellectual ability to effectively provide mental health services to this population. Insistence upon the use of traditional models of treatment will result in poor treatment outcomes and will prevent patients with ID from receiving appropriate care.16,17 This article will focus on common issues of concern that might arise in treatment, barriers that complicate treatment, and modifications in the provision of psychotherapy modalities that can increase the efficacy of the treatment provided.

Treatment Considerations

Cognitive deficits. Approximately 2 to 3 percent of the population has cognitive deficits and, of this subset, about 30 to 40 percent will experience mental health issues.1 With these statistics, all mental health programs should be equipped to deliver psychotherapy suited for individuals with cognitive deficits, as they will be integrated into virtually every practice setting.

Confidentiality. Patients with ID have the same legal expectations of confidentiality as those of individuals in the general population. Without assurance of confidentiality, the patient might withhold information in the room for fear of judgment or negative consequences.

Caregiver’s role. A parent, other family member/guardian/direct care staff member, or another interested party might need to accompany the patient for psychotherapy. The therapist must “manage the triangle” by interfacing with both patient and caregiver while attempting to direct most of the conversation to the patient.

Referral issues. In the general population, people typically self-refer for therapy. In the ID population, they are usually referred by others due to disruptive behavior.18–21 The referring party might assume the goal is the elimination of the maladaptive behavior. This might not be a concern for the patient. The patient might have anxiety related to the referral or might view it as punishment/consequence of bad behavior.

Understanding maladaptive behavior.There are many reasons for maladaptive behavior, and it is the work of the therapist to determine the meaning of the behavior. As Sigmund Freud said, “all behavior is purposeful.”22 It is the job of the therapist to assist the patient in communicating their thoughts, needs, and emotions. Through therapy, the psychiatrist can explore these behaviors, determine the underlying meaning, and assist the patient in communicating his or her needs more effectively.

Safe and trusting environment. It is crucial for the therapist to create a safe and trusting environment for the patient to discuss their emotions and symptoms. If there are behavior problems, but the patient doesn’t see the behavior as problematic, the therapist might explore the emotions attached and/or consequences of the behavior.

Clear expectations. The patient might not understand the purpose of therapy. They should be prepared with education and support that will enhance their participation and self-growth. The role of the therapist is unique and must be distinguished from other multidisciplinary team members. The therapist is not “yet another individual” in the patient’s life attempting to impose rules upon or making decisions for them. The individual should be reassured they are not being punished and might need education about what therapy is with explanations about why people seek treatment, what happens in the room, and what people talk about.

Communication. Incorporating open-ended questions gives the patient an opportunity to express themselves and tell their personal story. Key communication pointers include negotiating issues of communication openly, checking the patient’s degree of understanding, and “bringing it into the room.” Patients with ID are typically forthright and will clarify a misunderstanding if there is a solid therapeutic alliance in place. The therapist should establish that the cognitive deficits are a legitimate and neutral topic for discussion in psychotherapy.

Supportive Psychotherapy

The foundation of supportive psychotherapy is the positive relationship between the patient and therapist.19,23–25 In general, supportive psychotherapy is based on an interactive model10,26 in which the therapist utilizes a more directive approach through providing feedback, suggestions, and problem-solving during sessions. The therapist must maintain empathy so the patient has the opportunity to develop a positive therapeutic alliance. The therapist tries to create a “safe holding environment” for the patient to investigate and tolerate strong affects. This therapeutic relationship serves to reinforce strengths and move away from less-adaptive coping styles. Patients are taught to recognize, acknowledge, and label their emotions so they can develop healthy coping skills when experiencing painful emotions. Supportive psychotherapy is often used when patients are unable to tolerate other types of treatment, including during times of decompensation or elevated intensity of life stressors. The content of therapy is focused on the patient’s current life experiences and how those experiences affect their functioning. The therapist encourages the patient to become active in developing plans to meet goals in life.

Practice Points: Supportive Psychotherapy Adapted for ID

General. Supportive psychotherapy requires less adaptation because it is inherently more directive and more flexible.

Simplification. Therapists should simplify interventions during interactions; decrease the complexity of the techniques by dividing interventions into smaller units; and use short, direct phrases and match the mean length of utterance of the patient. So, if the patient uses four- to five-word phrases, the therapist should follow suit. Additionally, they should use concrete terms as needed—those with mild ID (~85% of this patient population) will take things literally and should avoid figurative speech and slang verbiage, as well as be willing to restate issues from a different perspective.

Length of appointments. The length of appointments should match the attention span of the patient. It is vital to utilize repetition to facilitate retention and generalization and include clarifying, recapping, and summarizing.

Length of treatment. Therapists should expect longer length of treatment in patients with ID. Most research indicates that length of care is 1 to 2 years for the ID population.16,27

Collaboration. Therapists should encourage the involvement of concerned others, including caregivers, family members, direct care staff, friends, and roommates. The caregiver can act as a bridge between sessions, helping to convey collateral data, usually at the beginning and/or end of sessions. The caregiver can also reinforce coping skills and assist with homework between appointments.

Augmentation. Treatment should be augmented with other activities, such as role-playing, drawings, and games. Therapists should follow cues and adjust the environment to match the unique sensory needs of the patient.

Transference/countertransference. Psychotherapists’ beliefs about and reaction to ID will affect the therapeutic process. The therapist’s feelings and assumptions regarding ID should be explored prior to and during provision of therapy with a supervisor or colleague as needed.

Clinical vignette. Mr. A is a middle-aged man with moderate ID and no history of mental health who presented for evaluation with a request to “talk to someone” about the death of both of his parents. Having lived his entire life with his family, he now struggles with the loss of his last remaining caregiver, which is also complicated by the loss of his family home, neighbors, and church. He is now living in a supported residential setting for the first time with new, unfamiliar staff.

Dr. M: It has been a very difficult time for you, having recently lost your father and living in a group home for the first time.

Mr. A: It’s hard. I don’t trust those people in the group home. I don’t know them. I think they are taking my money.

Dr. M: It is hard to trust new people. It will take some time. Has it been hard to trust me?

Mr. A: I trust you and told you how lonely I am. Why did my dad leave me?

Dr. M: Your dad did not choose to leave you. We are all born, live our lives, and then we all die. It is the cycle of life. It is normal to feel angry and sad when someone we love dies.

Mr. A: My dad didn’t want to leave me. It is the cycle of life.

Dr. M: That is true. And you have a lot of good people in your life to help you get through this. We are all on your team. You have a good supervisor at work and a supportive girlfriend. You can talk to any of us when you need help. Do you want me to talk to your group home manager when we finish our session today? We can make sure she is aware of what you need to feel supported between appointments.

Here, Dr. M reviews positive affirmations with the patient so they can be processed in the room. One suggestion is to utilize pictorial representations depending on the level of ID. For example, a key ring with laminated coping cards can be helpful. Dr. M also facilitates communication with a caregiver (with Mr. A’s permission) so she can assist with this intervention between appointments as needed.

Motivational Interviewing

Motivational interviewing is a type of psychotherapy that investigates the patient’s understanding of their maladaptive behaviors to determine whether or not they are motivated to change these behaviors.28–30 The therapist guides the patient to help them identify, explore, and resolve their ambivalence. Ambivalence is simultaneous conflicting feelings about moving on to the next stage of change, such as a patient stating, “I guess I could stop smoking, I just do not know if I want to. It seems like it would be hard, but it would be so much better for my health.”

Motivational interviewing is based on five stages of change: precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and maintenance.29,30 The therapist helps the patient progress through the stages using specific principles. In the precontemplation stage, the therapist focuses on raising awareness of the problem because the patient has not yet identified the behavior as a problem. In the contemplation stage, the patient has accepted the behavior as a problem, and the focus of therapy is instead to attempt to evoke reasons for change. In the preparation stage, the focus is on clarifying goals, then subsequently developing a plan to reach the goals. Finally, during the maintenance stage, the therapist works with the patient to reinforce the benefit of change.

As described first in 1983 by clinical psychologists Miller and Rollnick, there are four techniques often utilized in a motivational interview to lead a patient toward understanding their own problems and developing the motivation to create positive change.29,30 Open-ended questions facilitate forward-momentum communication. Forward-momentum communication can be described as the ability to utilize the strength or force gained thus far in the therapy to continue to dive deeper into the patient’s underlaying struggles with change. Affirmations, or emotional support or encouragement, enable patients to make changes by supporting the restructuring of the patient’s view. Reflective listening allows the patient to feel the psychotherapist understands their perspective. It also aids in resolving ambivalence through exploring how current behavior impacts their quality of life and the advantages of making positive changes. Summaries, a specific type of reflective listening in which the therapist highlights both sides of the patient’s ambivalence.

Clinical vignette. Dr. M: It sounds like you are frustrated about the limited amount of money you have to go out to eat each month. Have you thought about your spending?

Ms. B: My staff told me it is because I am smoking more cigarettes and that is why I can’t go out to eat.

Dr. M: Have you thought about making any changes?

Ms. B: I want to quit smoking.

Dr. M: That would be a good decision. If you quit smoking, how would that make things different?

Ms. B: I could go out to eat more because I would have more money.

Dr. M: What else would it change?

Ms. B: I would feel better. I have a bad cough when I smoke.

Dr. M: If you have decided to quit, you could choose a day and make some changes starting then. You could give your ashtrays and lighters to someone else and talk to your staff about your decision.

Ms. B: I want to quit this weekend. Can you talk to my staff and let them know? I need them to help me. I want to go out to restaurants with my friends.

Practice Points: Motivational Interviewing Adapted for ID

General. Be more directive and more direct in describing the positives of the undesired behavior. In motivational interviewing with a patient with ID, the therapist must help the patient identify specific feelings regarding the possibility of change, which often requires a more directive approach. People with ID typically understand the risks of smoking, drinking, and overeating just as the general population does. Give them a chance to demonstrate their knowledge.

Communication. Always address barriers in communication. Utilizing role-playing, visual prompts, images, or games might help to better involve the patient.

Caregiver’s role. It is vital that staff supports the patient’s processing during motivational interviewing. Importantly, they should focus on not interfering. For example, when a therapist asks a patient to say the negative things about smoking, staff often will interrupt to tell the patient that smoking causes cancer. Most patients with ID engaged in motivational interviewing know this fact; therefore, it would be more beneficial for the caregiver to utilize active listening in this situation.

Grief and loss. Most individuals with ID have suffered multiple losses and/or abandonment. The therapist should attempt to characterize the Developmental stage and concept of loss/death at that stage. In the Sensorimotor stage, which includes most individuals with profound ID, losses are experienced as a constantly unfulfilled expectation; they will require repetition to understand the loss is permanent. In the Preoperational stage, which includes most individuals with severe/moderate ID, the patient will ask questions such as, “Who will take care of me?,” “How will the loss affect me?,” and “How will I get the things I need?” There might be fantasy and magical thinking in the Preoperational stage as well. In the Concrete Operations stage, which includes most individuals with mild/moderate ID, the individual understands clear and specific explanations. They tend to take things literally.

CBT

CBT focuses on challenging and changing a patient’s distorted thoughts that might have caused both maladaptive behaviors and negative emotions.31–33 The structure of CBT is required to target specific problems and possible solutions. The two distinct psychological theories, cognitive therapy and behavioral therapy, are integrated in this evidence-based form of psychotherapy.34,35 Cognitive therapy helps patients to resolve symptoms through identifying and altering dysfunctional thinking.35,36 Behavioral therapy focuses on replacing undesirable behaviors with more adaptive behaviors. The session begins with the therapist and patient working to set an agenda, which determines the specific issue of concern. The target symptom(s) are then assessed.36,37 Homework from the previous session is reviewed and the agenda items are explored. Finally, homework for the next session is assigned, and the therapist asks for feedback from the patient about the session. A course of CBT normally lasts between five and 20 sessions.

As described by Beck in the 1960s, there are three levels of cognition that are investigated in CBT: automatic thoughts, intermediate beliefs, and core beliefs.33,35,36 Schemas are core beliefs that are shaped by developmental influences and life experiences and are the key to understanding how a patient’s core beliefs have developed into symptoms that cause them to seek treatment. It is imperative that the therapist and patient work together to analyze the patient’s cognitive distortions and maladaptive schema to test the validity of the belief and make modifications when appropriate. The main goal of CBT is to alter the patient’s perspective of themselves and the world around them.32,37

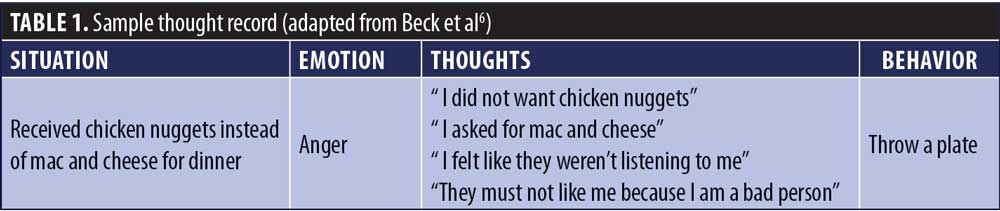

Clinical vignette. Miss B: I threw my dinner plate last night.

Dr. P: Tell me about your dinner last night.

Miss B: It was chicken nuggets and not mac and cheese like I asked for.

Dr. P: What emotion were you feeling when you saw your plate?

Miss B: I was angry.

Dr. P: So, you were feeling angry; feeling angry is okay. It is not a problem that you were feeling angry, it is a signal. What were you thinking when you were angry?

Miss B: I was thinking that I did not want chicken nuggets.

Dr. P: Then what was your next thought?

Miss B: I was then thinking I asked for mac and cheese.

Dr. P: Then what was your next thought?

Miss B: I felt like they weren’t listening to me.

Dr. P: Then what was your next thought?

Miss B: They must not like me because I am a bad person.

Dr. P: I hear that you were mad, and your thoughts went from not getting what you wanted for dinner and they progressed to the staff not liking you because you are a bad person.

Miss B: Yes.

Dr. P: Okay, and the behavior connecting the thoughts and emotions was throwing your plate. Let’s fill out this thought record [Table 1] together to make sure we reinforcement these connections.

Patients with ID often have difficulties expressing internal thoughts/emotions. Patients might have past experiences of being discouraged from expressing emotions and might need permission to express or even feel an emotion. The therapist helps the patient learn to see emotions as “signals” versus problems, with the goal of restoring the patient’s sense of self-control. This clinical case would progress to the therapist helping the patient to reframe events with an emphasis on situations when patient acted competently. The therapist should attempt to reframe distressing events/behaviors as signs of coping.

Practice Points: CBT Adapted for ID

General. Abstract concepts, such as cognitive distortions, might be difficult for patients to understand. It will be important to slow the rate at which concepts are covered relative to that with the normal population. Once again, increasing the number of sessions and using repetition might help to facilitate internalization.

Combat learned helplessness with collateral support. Patients with ID experience failure at a higher rate than the general population.1,26 Most individuals with ID might enter new situations with the expectation of failure. Because of their disabilities, they often have outer-directed orientation; they are overly dependent on others by definition and might look toward others as a guide for their own behavior. Therefore, the role models/caregivers/mentors in a patient’s life are pivotal. Therapists should involve these care providers to help the patient recognize patterns of behaviors and assist with completion of homework assignments.

Reframing events. It is important that individuals in therapy are open to reframing events to better understand them. Effective strategies for reframing beliefs include asking evidence-based questions, such as, “Does the data match the patient’s belief?,” asking alternative based questions, such as, “Are there alternate ways to explain events?,” and asking implication-based questions, including, “Does the data mean everything the patient thinks it means?”

Identifying emotions. Patients with ID have difficulties with expressed emotion; they might not have the skills to label, identify, or communicate feelings nor those required to problem-solve or develop solutions. The psychotherapist can help these individuals to develop language or alternate means to communicate emotions and teach them words and gestures or how to use pictures and journaling as additional outlets. One high-yield intervention involves using a poster of faces expressing various emotions. This can help the individual identify and communicate emotions to others.

Exploring emotions. Therapists should provide opportunities for the patient to share emotions.

Interpret behavior. Behavior is a form of communication. Therapists should provide reassurance that it’s possible and effective to communicate big or painful feelings without hurting oneself or others.

Conclusion

Psychotherapy is an evidence-based practice with proven efficacy in the ID population. The goal of therapy is self-growth, discovery, and positive change. The therapist must be flexible and adapt their techniques to better fit with these individuals’ cognitive deficits. This often requires a modification of the mode of therapy to accommodate individual differences, as well as the acuity and nature of symptoms. During sessions, therapists should explore issues of disability, dependence, and losses endured. Overall, therapists should support a positive view of the self and focus on the patient’s abilities. Finally, it is a myth that patients with ID cannot benefit from the full range of mental health services, including psychotherapy, behavior therapies, and state-of-the-art pharmacologic regimens.

References

- Baxter JT, Cain NN. Psychotherapeutic Interventions. Training Handbook of Mental Disorders in Individuals with Intellectual Disability, 2006. 115–130. NADD Press. Kingston, NY.

- Martin A. Intellectual disability, trauma and psychotherapy. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2010;23(3):301–310.

- Esterhuyzen A, Hollins S. (1997) Psychotherapy in Psychiatry in Learning Disability. (ed. S. Read), pp. 332–349. London: W. B. Sanders.

- Prout HT. The Effectiveness of Psychotherapy with Persons with Intellectual Disabilities. Psychotherapy for Individuals with Intellectual Disability, 2011. 265-287. NADD Press. Kingston, NY.

- Mevissen L, de Jongh A. PTSD and its treatment in people with intellectual disabilities: a review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(3):308–316.

- Whitehouse RM, Tudway J, Look R, Kroese B. Adapting individual psychotherapy for adults with intellectual disabilities: a comparative review of the cognitive-behavioural and psychodynamic literature. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2006;19: 55–65.

- Davidson PW, Cain NN. Overview. Training Handbook of Mental Disorders in Individuals with Intellectual Disability, 2006. 1–13. NADD Press. Kingston, NY.

- Douglas C. Teaching supportive psychotherapy to psychiatric residents. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:445–452.

- Fernado K, Medlicott L. My shield will protect me against the ants: treatment of PTSD in a client with intellectual disability. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2009;34(2):187–192.

- Gentile JP, Jackson CS. Supportive psychotherapy with the dual diagnosis patient. Psychiatry. 2008;5(3):49–57.

- Frielink N, Embregts P. Modification of motivational interviewing for use with people with mild intellectual disability and challenging behaviour. J Intellect Dev Disabil. 2013;38(4):279–291.

- Surley L, Dagnan D. A review of the frequency and nature of adaptations to cognitive behavioural therapy for adults with intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2019;32(2):219–237.

- Barrera C. (2017). Cognitive behavior therapy with adults with intellectual disabilities: a systematic review. Sophia, the St. Catherine University repository website. https://sophia.stkate.edu/msw_papers/707. Accessed June 30, 2019.

- Pert C, Jahoda A, Stenfert Kroese B, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy from the perspective of clients with mild intellectual disabilities: a qualitative investigation of process issues. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2013;57(4):359–369.

- Dagnan D. Psychosocial interventions for people with intellectual disabilities and mental ill-health. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(5):456–460.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Trauma Informed Care and Trauma Services. http://www.samhsa.gov/nctic/trauma.asp. Accessed August 31, 2019.

- Willner P. The effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions for people with learning disabilities: a critical overview. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2005;49(1):73–85.

- Berry P. Psychodynamic therapy and intellectual disabilities: dealing with challenging behaviour. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education. 2003;50:39–51.

- Gentile JP, Hubner ME. Bereavement in patients with dual diagnosis mental illness and developmental disabilities. Psychiatry. 2005;2(10):56–61.

- Mitchell A, Clegg J, Furniss F. Exploring the meaning of trauma with adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Applied J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2006;19: 131–142.

- Murphy GH, O’Callaghan AC, Clare ICH. The impact of alleged abuse on behaviour in adults with severe intellectual disabilities. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2007;51(10):741–749.

- Bowlby J. (1969). Attachment and Loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. London: Hogarth Press and Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

- Battaglia J. Five keys to good results with supportive psychotherapy. Curr Psychiatr. 2007;6:27–34.

- Blackman NJ. Grief and intellectual disability: a systematic approach. J Gerontol Soc Work. 2003;38(1/2):253–263.

- Clute MA. Bereavement interventions for adults with intellectual disabilities: what works? Omega. 2010;61(2):163–177.

- Misch D. Basic strategies of dynamic supportive therapy. Focus. 2006;4:253–268.

- Wink LK, Erickson CA, Chambers JE, McDougle CJ. Comorbid intellectual disability and borderline personality disorder: a case series. Psychiatry. 2010;73(3):277–287.

- Arkowitz H, Westra H. Introduction to the special series on motivational interviewing and psychotherapy. J Clin Psychol. 2009;65:1149–1155.

- Atkinson C. Using solution-focused approaches in motivational interviewing with young people. Pastoral Care. 2007;31–37.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational Interviewing: Preparing People for Change. 2002. New York: Guildford Press.

- Beck AT, Rush AJ, Shaw BF, Emery G. Cognitive Theory of Depression. 1979. The Guilford Press. New York, NY.

- Jahoda A, Dagnan D, Jarvie P, Kerr W. Depression, social context and cognitive behavioural therapy for people who have intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2006;19:81–89.

- Leichsenring F, Hiller W, Weissberg M, Leibing E. Cognitive-behavioral therapy and psychodynamic psychotherapy: techniques, efficacy, and indications. Am J Psychother. 2006;60(3):233–259.

- Maerov P. Demystifying CBT: effective, easy-to-use treatment for depression and anxiety. J Fam Pract. 2006;5(8): 27–39.

- Romana MS. Cognitive-behavioral therapy. Treating individuals with dual diagnoses. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2003;41(12):30–35.

- Taylor JL, Lindsay WR, Willner P. CBT for people with intellectual disabilities: emerging evidence, cognitive ability and IQ effects. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2008;36(6):723–733.

- Wright J. Cognitive behavior therapy: basic principles and recent advances. Focus. 2006;4:173–178.