by Jennifer M. Giddens and David V. Sheehan, MD, MBA

by Jennifer M. Giddens and David V. Sheehan, MD, MBA

J. Giddens is the Co-founder of the Tampa Center for Research on Suicidality, Tampa, Florida; and Dr. Sheehan is Distinguished University Health Professor Emeritus, University of South Florida College of Medicine, Tampa, Florida.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2014;11(9–10):182–190

Funding: There was no funding for the development and writing of this article.

Financial Disclosures: J. Giddens is the author and copyright holder of the Suicide Plan Tracking Scale (SPTS) and is a named consultant on the Sheehan-Suicidality Tracking Scale (S-STS), the Sheehan-Suicidality Tracking Scale Clinically Meaningful Change Measure Version (S-STS CMCM), the Pediatric versions of the S-STS, and the Suicidality Modifiers Scale; Dr. D. Sheehan is the author and copyright holder of the S-STS, the S-STS CMCM, the Pediatric versions of the S-STS, the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), and the Suicidality Modifiers Scale, is a co-author of the SPTS, and owns stock in Medical Outcomes Systems, which has computerized the S-STS.

Key Words: Suicide scale, suicide assessment, suicide risk, suicide, suicidal ideation, impulsive suicide, impulsive suicidality, suicidality, C-SSRS, S-STS, better off dead

Abstract: Objective: The author of the widely used suicidality scale, the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale, has repeatedly made the claim that asking the question, “Do you think you would be better off dead?” in suicidality assessment delivers false positive results. This case study investigates the value of this question as an immediate antecedent to impulsive suicidality and as a correlate of functional impairment. Method: One subject with daily suicidality and frequent impulsive suicidality rated five passive suicidal ideation phenomena and impulsive suicidality daily on a 0 to 4 Likert scale and rated weekly functional impairment scores for 13 weeks on a 0 to 10 Discan metric. Results: Each of the five passive suicidal ideation phenomena studied frequently occurred at a different severity level, and the five phenomena did not move in synchrony. Most passive suicidal ideation phenomena were very low on dates of impulsive suicidality. Thoughts of being better off dead were a frequent antecedent to impulsive suicidality and were related to an increase in functional impairment. Conclusion: The relationship to both functional impairment and impulsive suicidality suggest that it is potentially dangerous to ignore thoughts of being better off dead in suicidality assessment.

Introduction

The value in asking the question, “Do you think you would be better off dead?” during a suicide assessment is a matter of controversy. Some scales including the Sheehan-Suicidality Tracking Scale (S-STS),[1] InterSePT Scale for Suicidal Thinking (ISST),[2] Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9),[3] and the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)[4] routinely include this question. Other groups[5–7] have taken a different position. One author, for example, has repeatedly stated, “We do not consider thoughts that you would better off dead to be anything.”[8,9] This author asserts that questioning patients about the thought that they would be “better off dead” delivers “false positive results,”[10–14] adding that these patients “should not have been called suicidal.”[12] This latter advice was given to and accepted by the United Stated Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and is reflected in the FDA suicidal ideation category, “Passive suicidal ideation: wish to be dead” (line 470).[7] In support of this claim, Posner[5] cited a study by Katzan et al[15] at the International Academy of Suicide’s World Congress on Suicide 2013. That study[15] investigated the relationship between question 9 in the PHQ-9 (“thoughts that you would be better off dead or of injuring yourself in some way”3) and the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale[5] (C–SSRS). In a sample of 1,461 subjects, question 9 on the PHQ-9 was positive in 269 cases when the C–SSRS was negative, and was positive in only 78 cases when the C–SSRS was positive. The positive predictive value for question 9 on the PHQ-9 against the C–SSRS was 22.5 percent. Because of this poor relationship, the author15 concluded that question 9 on the PHQ-9 lacked any value as a screening question in suicidality assessment. Another equally plausible and alternative explanation of the same data, however, is that the C–SSRS is incomplete in assessing passive suicidal ideation.

In a follow-up, structured, telephone interview of 330 cancer patients who responded positively to question 9 on the PHQ-9, Walker et al[16] found that one third reported still “having thoughts that they would be better off dead, but not of suicide, and another third reported clear thoughts of committing suicide.” In light of these findings, it appears potentially dangerous to dismiss the question about “thoughts that you would be better off dead” as having no value.

The purpose of the following case study is to investigate the value of including the question, “Do you think you would be better off dead?” in the assessment of passive suicidal ideation, as an immediate antecedent to impulsive suicidality, and as a correlate of functional impairment associated directly with suicidality.

Methods

This case study presents a prospectively collected, self-report data series on five passive suicidal ideation phenomena and one measure of impulsive suicidality over a 13-week period. A 31-year-old female subject diagnosed with Asperger syndrome collected detailed daily data on her events of suicidality. The subject had some suicidality on a daily basis for several years. She rated the severity of these six suicidal phenomena daily on a 0 to 4 (5-point) Likert scale with descriptive anchors (0=not at all, 1=mild, 2=moderate, 3=severe, 4=extreme). These phenomena were 1) the thought “I would be better off dead,” 2) the thought “I need to be dead,” 3) the thought “I wish I were dead,” 4) the thought “I wish I could go to sleep and not wake up,” 5) the thought “I wish I was not alive anymore,” and 6) impulsive suicidality.

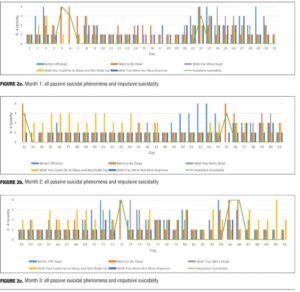

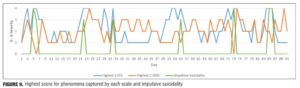

Of the six phenomena assessed, we view impulsive suicidality as the greatest danger. Data for all five of the above passive ideation phenomena were then plotted against the impulsive suicidality to highlight the relationship between each of these phenomena and the impulsive suicidality. The results from this analysis are shown in Figures 1 through 9.

The subject collected weekly tracking on the functional impairment and quality of life experienced due to suicidality over the same timeframe using a 0 to 10 (11-point) Discan metric.

The functional impairment questions were 1) “The suicide symptoms have disrupted your work / school work,” 2) “The suicide symptoms have disrupted your social life / personal relationships / leisure activities,” and 3) “The suicide symptoms have disrupted your family life / home responsibilities” followed by the quality of life question 4) “The suicide symptoms have disrupted the quality of your life.”

The subject also recorded her responses to these functional impairment questions daily over the last month of the timeframe under study, using a 0 to 10 (11-point) Discan metric to more precisely study the relationship between daily fluctuations in impairment, quality of life, the five passive suicidal ideations, and impulsive suicidality. These questions and metric (adapted from the Discan metric used in the Sheehan Disability Scale 2009[17]) were taken from page 9 of the 11/12/13 version of the S-STS Clinically Meaningful Change Measure (CMCM).[1]

Result 1. Figure 1 illustrates the subject’s daily severity ratings of “I would be better off dead” and impulsive suicidality. It shows that in the days before the impulsive suicidality, she had 2 to 5 days of feeling that she would be better off dead before the onset of the impulsive suicidality.

Discussion. The findings in this case study suggest that the thought “I would be better off dead” can be an important and recurrent antecedent of more serious suicidality in some patients. The subject of this case study had a lifetime history of 33 non-halted suicide attempts. Of these attempts, 31 were episodes of impulsive suicidality. The “better off dead” thought/feeling occurred prior to 31 of these episodes of impulsive suicidality. The “better off dead” thought/feeling occurred prior to or during 32 of the non-halted attempts. The most serious attempt resulted in spending three days in a coma in an intensive care unit. That attempt occurred during an episode of impulsive suicidality that occurred the day following thoughts of being “better off dead.” For this reason, we believe an affirmative response to the question, “Do you think you would be better off dead?” should be taken seriously and should always be asked when assessing suicidal ideation and behavior.

Result 2. Figures 2a, 2b, and 2c capture the subject’s daily ratings on the thoughts “I would be better off dead,” “I need to be dead,” “I wish I were dead,” “I wish I could go to sleep and not wake up,” and “I wish I was not alive anymore” and on the subject’s impulsive suicidality over the same timeframe.

Discussion. The results show that the “wish to be dead” was usually inversely related to the impulsive suicidality within each 24-hour period over time. Even though the subject stated that the impulsive suicidality was alarming because she experienced it as pulling her toward suicide, she reported that her instinct was to fight against it, to feel alarmed by it, to resist it, and to wish for an opposite outcome in order to stay alive. We have found that patients who are impulsively suicidal do not always acutely wish to be dead at the same moment and often wish to get help in resisting these impulses. In our experience, this may not be generally recognized or understood by other clinicians and/or clinical investigators.

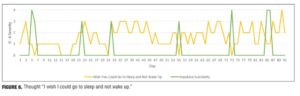

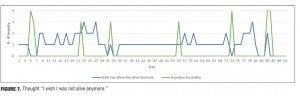

Result 3. These five types of passive suicidal ideation did not move completely synchronously with each other even though they were present most days. For example, on Day 6 in Figures 2a and 3, the severity of the thought “I need to be dead” was elevated, while all other passive ideations were nonexistent. They did not all move in precise synchrony with impulsive suicidality (Figures 2a–c, 4, 5, 6, and 7). For example, on Day 22, the thought “I would be better off dead” (Figure 1), the thought “I need to be dead” (Figure 4), and the impulsive suicidality moved in the opposite direction to the thought “I wish I were dead” (Figure 5).

Discussion. All the above passive ideation variants did not change to the same degree on the same day and were not synchronous with each other in this subject with daily suicidality. Consequently, in this case, they were not substitutable for each other.

Result 4. Figure 5 shows an increase in the thought “I wish I were dead” following most spikes in impulsive suicidality. The subject explained that the reason for this increase in severity of the thought “I wish I were dead” is because the impulsive suicidality was so frightening that she wished she was dead in order to avoid having to experience the impulsive suicidality again.

Discussion. A passive suicidal thought may be the result of another prior suicidal phenomenon, rather than its antecedent.

Result 5. Figure 3 shows all five of the passive suicidal phenomena experienced over the timeframe studied. The thought “I would be better off dead” was more severe than all other passive suicidal phenomena on several days. Figure 3 illustrates two timeframes (Days 48–54 and Days 29–31) during which the thought “I would be better off dead” was rated at either a 3 or a 4, while all other passive suicidal phenomena were rated between 0 and 2.

Discussion. If we were to ignore the thought “I would be better off dead” for these timeframes, this subject’s passive suicidal phenomena would be collectively rated much lower than actually experienced.

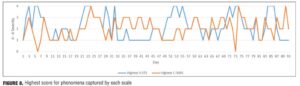

Result 6. Figure 8 shows the highest score of the three passive suicidal ideation phenomena captured by the S-STS and of the three passive suicidal ideation phenomena captured by the C–SSRS on the same day. The S-STS captured the following three passive suicidal ideation phenomena: 1) the thought “I would be better off dead,” 2) the thought “I need to be dead,” and 3) the thought “I wish I were dead,” while the C–SSRS captured the following three passive suicidal ideation phenomena: 3) the thought “I wish I were dead,” 4) the thought “I wish I could go to sleep and not wake up,” and 5) the thought “I wish I was not alive anymore.”

With the exception of Day 17, Days 33 through 44, Day 65, Days 67 through 69, Day 76, Day 83, and Days 87 through 91 (24 days out of a total of 91 days), the S-STS captured the passive suicidal ideation that was at least the most severe on any given day. For 23 of these 24 days, the highest score on the C–SSRS was related to the thought “I wish I could go to sleep and not wake up.” Although four of the five types of passive suicidal ideation were low during this timeframe, the highest C–SSRS score was associated with the question that endorsed the “wish to go to sleep and not wake up” for a prolonged period of time, rather than wishing to go to sleep and never waking up.

Discussion. If the desire to “go to sleep and not wake up” for a prolonged period of time is not considered to be suicidal ideation (since there was no desire to die or thought of dying associated with this thought), then the S-STS captured the most severe passive suicidal ideation phenomena, while the C–SSRS captured less severe passive suicidal ideation phenomena and also captured the above non-suicidal ideation some of the time. In other words, we posit that the C–SSRS wording “wish to go to sleep and not wake up” could also capture a non-suicidal need to go to sleep for a prolonged period of time because of a sense of profound exhaustion, rather than a suicidal desire to die while sleeping. The former is a false positive while the latter is not.

Result 7. Figure 9 has the same data as in Figure 8 with the addition of the severity of the impulsive suicidality. On five of the six days of impulsive suicidality, the highest score for the passive ideation phenomena captured by the C–SSRS was two points lower than the highest score of the passive suicidal ideation phenomena captured by the S-STS. On two of these six dates (Day 6 and Day 73), the C–SSRS passive suicidal ideation score was 0. This is due to the thought, “I need to be dead,” which is not on the C–SSRS, but is on the S-STS, being rated as extreme on the days of the impulsive suicidality under study.

Discussion. More often than not, the C–SSRS underestimated the passive suicidal ideation phenomena that occurred on the days of impulsive suicidality in this case study.

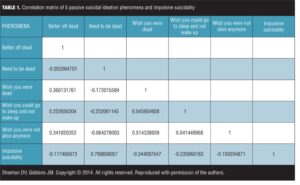

Result 8. Table 1 is the correlation matrix of the five passive suicidal ideation questions and impulsive suicidality. The S-STS has the first three of these questions while the C–SSRS has the last three of the five passive suicidal ideations. The S-STS and the C–SSRS both captured the thought, “I wish I were dead” (question 3). The three S-STS questions were only weakly and sometimes negatively correlated with each other. Consistent with and for the same reasons cited in Results 7 above, there was a high correlation between the “need to be dead” and impulsive suicidality (0.79).

Discussion. In order to capture the broadest range of passive suicidal ideation experiences using the fewest number of questions from the five available, the best strategy was to select those that were not correlated well with each other and to include even those negatively correlated with each other, if available. Based on the above “choice strategy,” the three questions in the S-STS had broad diversity, while the three C–SSRS questions had less diversity.

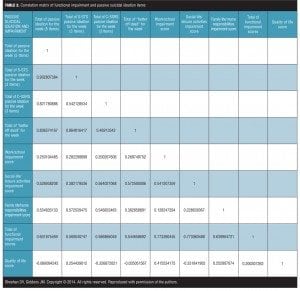

Result 9. Table 2 investigates the relationship between a positive response to the passive suicidal ideation question, “Do you think you would be better off dead?” and work/ school impairment, social/leisure impairment, family life/home responsibility impairment, total functional impairment, and quality of life scores. These results reflect the impairment scores captured weekly and the sum of the daily scores for the same week for all five passive ideations. It also investigates the relationship between the S-STS passive ideation score, the C–SSRS passive ideation question, and the same measures of impairment and quality of life. The above results are very similar to those found in studying the relationship between the daily impairment and quality of life scores and the daily passive ideation scores.

Discussion. “Better off dead” and functional impairment. The results show a good correlation between thoughts of being better off dead and social life/leisure activities impairment (0.57) and total functional impairment scores (0.54). The relationship between thoughts of being better off dead and family life/home responsibilities score were modest (0.38). There was a weak positive relationship between work/school impairment score and thoughts of being better off dead (0.26). This suggests that a positive response to the “better off dead” question is associated with work, family life, social life, and total functional impairment. The failure of the C–SSRS to ask about thoughts of being better off dead leads the C–SSRS passive ideation (and therefore cumulative C–SSRS ideation scores) to underestimate the functional impairment associated with thoughts of being better off dead.

There was no meaningful correlation between thoughts of being better off dead and quality of life score. This lack of correlation may be because the “better off dead” thought often occured prior to the impulsive suicidality, which made the quality of life score acutely worse.

“Better off dead” and scale scores. The “better off dead” thought was highly correlated with both the total of the S-STS passive ideation score (3 items) question and the total of all five of the passive ideation items (0.86 and 0.83, respectively). The correlation of thoughts of being better off dead was considerably lower with the total of the C–SSRS passive ideation score (3 items) question (0.46). These findings suggest that the thoughts of being better off dead make a larger contribution than expected in the passive ideation item totals (the total for all 5 and the total set of 3 passive ideation items on the S-STS).

There was a negative, inverse relationship between the passive ideation score on the C–SSRS and the disruption to quality of life (-0.32). As the passive ideation score on the C–SSRS worsened, the quality of life improved. There was a weak positive correlation (0.25) between the passive ideation score on the S-STS and the disruption to quality of life. In contrast, there was no significant relationship between the “better off dead” question or the total of all five of the items of passive ideation and the disruption to quality of life score (-0.03 and -0.06, respectively). On first inspection, this seems like a puzzling finding. When presented with this finding, the subject’s response was as follows:

“That makes sense. First, I feel that I would be better off dead. Then I experience impulsive suicidality. Immediately after the impulsive suicidality [episode], there is a reduction in symptoms. Physical exhaustion typically follows this within one day. The reduction in suicidality symptoms results in an improvement in the quality of life score, and the severe physical exhaustion results in a desire to ‘go to sleep and not wake up’ for a long period of time, but not necessarily the desire to die during this sleep. Since the desire to ‘go to sleep and not wake up’ is part of the C–SSRS passive suicidal ideation category, this results in an increase in the C–SSRS score in this category.”

Discussion

The authors consider the thought of being better off dead as one type of passive suicidal ideation. This type of passive suicidal ideation can occur alone in the absence of any of the other passive suicidal ideation. Paradoxically, in our case study, this thought was not associated with a significant change in perceived quality of life in the timeframe immediately surrounding the experience, even when it was associated with an increase in functional impairment during this time.

Limitations. The limitations of this case study are that it is a case study of one subject. The subject may be outlier, and the findings may not be generalizable to other cases of suicidality.

Conclusion

The authors consider that asking the question, “Do you think that you would be better off dead?” is important and has value in all assessments of suicidality and can be an immediate antecedent to impulsive suicidality; is associated with an increase in family life/home responsibilities, social life/leisure activities, and total functional impairment; and was a consistent antecedent to 97 percent of the subject’s lifetime non-halted suicide attempts. The combination of the three types of passive ideation in the S-STS appears to capture a wider diversity of possible questions probing passive suicidal ideation than the C–SSRS.

References

1. Sheehan DV, Sheehan IS, Giddens JM. Status Update on the Sheehan-Suicidality Tracking Scale (S-STS) 2014. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2014;11(9–10):93–140.

2. Lindenmayer JP, Czobor P, Alphs L, et al. InterSePT Study Group. The InterSePT scale for suicidal thinking reliability and validity. Schizophr Res. 2003;63:161–170.

3. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;16(9):606–613.

4. Montgomery SA, Åsberg M. A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. Br J Psychiatry. 1979;134:382–389.

5. Posner K., Brown GK, Stanley B et al. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168:1266–1277.

6. United States Food and Drug Administration, United States Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry: Suicidality: Prospective Assessment of Occurrence in Clinical Trials, Draft Guidance. September 2010. https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2010/09/09/2010-22404/draft-guidance-for-industry-on-suicidality-prospective-assessment-of-occurrence-in-clinical-trials. Accessed October 1, 2014.

7. United States Food and Drug Administration, United States Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry: Suicidality: Prospective Assessment of Occurrence in Clinical Trials, Draft Guidance. August 2012. Revision 1. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM225130.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2014.

8. Columbia University Psychiatry Department. What we really know about suicide and medications

(video). March 28th, 2012; 54:32 minutes into the video. Available at: http://www.veomed.com/ va041172402012. Accessed January 2014.

9. Grand Rounds 2011 (video). Child Center of New York University (NYULMC). October 28, 2011. See at 48:20 minutes. Accessed online November 20, 2012. Available on request from [email protected].

10. Posner K. C-CASA and C-SSRS in CNS clinical trials: development and implementation. Presentation at the IOM Workshop on CNS Clinical Trials: Suicidality and Data Collection. Washington, DC: June 16, 2009.

11. Posner K. Suicide risk assessment and the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C–SSRS): improved precision with reduced burden. http://www.google.com/urlsa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CC0QFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.commondataelements.ninds.nih.gov%2Fdoc%2FCSSRS%2520Additional%2520Information.pdf&ei=JPr_Ut2UKZTGkQfct4D4AQ&usg=AFQjCNE7nBFxbvO0Mcgsg3zr2spMhvck9g&bvm=bv.61535280,d.eW0&cad=rja. Accessed October 1, 2014.

12. Suicide: a major public health crisis—a Firestorm webinar featuring Dr. Kelly Posner (video). June 28, 2013. http://www.youtube. com/watch?v=fYqcIt-Ul6Q. Accessed October 1, 2014.

13. Posner K. On the road to prevention: using the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale to increase precision and redirect scarce resources. Depression Center. University of Michigan. February 17, 2012. http://www.depressioncenter.org/colloquium/2012/downloads/posner-k_20120217.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2014.

14. Posner K. Issues in measuring suicidality on college campuses: the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale. The Suicide Prevention Resource Center. September 24, 2008. http://www.sprc.org/sites/sprc.org/files/Webinar_Measuring_Suicidality_CSSRS_9_24_08.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2014.

15. Posner K. Improving suicide screening at the Cleveland Clinic through electronic self-reports: PHQ-9 and the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C–SSRS). Poster presentation. International Academy for Suicide Research 2013 World Congress on Suicide. Montreal, Canada: June 10, 2013.

16. Walker J, Hansen CH, Butcher I et al. Thoughts of death and suicide reported by cancer patients who endorsed the “suicidal thoughts” item of the PHQ-9 during routine screening for depression. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(5):424–427.

17. Sheehan KH, Sheehan DV. Assessing treatment effects in clinical trials with the Discan metric of the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;23(2):70–83.