by Jonathan R. Scarff, MD, and Steven Lippmann, MD

Dr. Scarff is Staff Psychiatrist, Veterans Affairs Medical Center in Lexington, Kentucky. Dr. Lippmann is Professor Emeritus, University of Louisville School of Medicine in Louisville, Kentucky.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the contents of this article.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2023;20(10–12):49–54.

Abstract

Persistent postural perceptual dizziness (PPPD) is a functional neurological disorder characterized by troublesome feelings of dizziness and might be precipitated by vestibular events, postural changes, psychopathologies, and/or a person’s perceptual experiences. The diagnosis is confirmed by assessing a patient’s history. A variety of psychiatric symptoms are associated with PPPD; anxiety and depression are the most common. Psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy can be clinically helpful in reducing psychiatric symptoms and dizziness. Early intervention improves prognosis.

Keywords: Persistent postural perceptual dizziness, PPPD, vertigo, functional, neurology, cognitive behavioral therapy, SSRI, SNRI

Persistent postural perceptual dizziness (PPPD) is a functional neurological disorder, affected by structural and psychological factors.1 Precursor names for PPPD include phobic postural vertigo (PPV), visual vertigo (VV), space-motion discomfort (SMD), and chronic subjective dizziness (CSD). It might be among the most common causes of chronic dizziness, but symptoms are likely under-reported.2 Associated psychological conditions lead to significant impairment. Multidisciplinary treatment of psychiatric symptoms includes psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy and may improve dizziness. A literature review to identify psychotherapy and medication studies to attenuate psychiatric symptoms is provided below as a treatment guide for clinicians.

Methods

The authors conducted electronic searches of Ovid and PubMed databases for English language articles published from January 2000 through January 2023. Search terms included “persistent postural perceptual dizziness,” “chronic subjective dizziness,” “visual vertigo,” “space-motion discomfort,” “psychotherapy,” “medication,” and “treatment.” The titles and abstracts (if available) of 80 search results were reviewed. Full text articles were retrieved if needed. References in retrieved articles were reviewed for additional relevant information. Randomized, controlled trials (RCTs) and less robust study designs, such as non-RCTs and retrospective cohort studies, were included. Excluded were reports only describing treatment of physical symptoms, such as dizziness or imbalance (e.g., vestibular rehabilitation [VR], virtual reality, vestibular suppressant medications). Case reports and non-peer-reviewed articles were also excluded.

Overview of PPPD

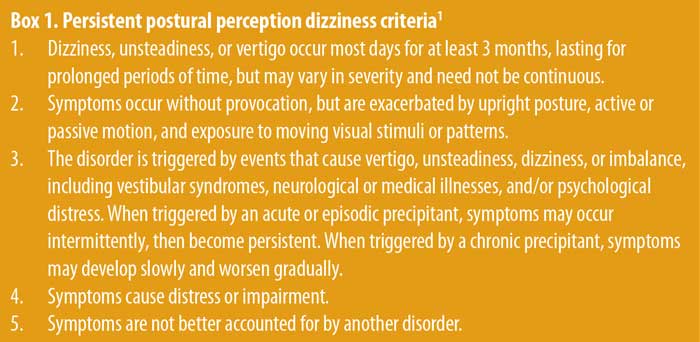

Description. PPPD was coined to reflect the diagnostic criteria of persistent, nonvertiginous dizziness exacerbated by postural challenges and perceptual sensitivity (Box 1).1 It may be categorized into “visual dominant,” “active-motion dominant,” and “mixed” subtypes.3 In addition to dizziness or unsteadiness, patients may report episodes of depersonalization, derealization, “brain fog,” disorientation, memory loss, trouble concentrating, and/or difficulty at multitasking.4 The prevalence of PPV or CSD was about four percent in British general medical practices and 15 to 20 percent in neuro-otology clinics.1,5 Most patients are female, with an average age between 40 to 49 years.1,6 There are no pathognomonic findings on neurological examination, laboratory testing, or neuroimaging.1 A diagnosis of PPPD is not determined by exclusion but is achieved by taking a clinical history which meets diagnostic criteria.7

Pathogenesis. The etiology of PPPD is multifactorial. Precipitating events include peripheral or central vestibular pathology (25%), vestibular migraine (20%), panic attacks/generalized anxiety disorder (15%), mild traumatic brain injury or whiplash (15%), autonomic dysfunction (7%), dysrhythmias (3%), and/or drug reactions (3%).1 Following such an event, a mismatch occurs between expected and actual sensory input, with preference given to visual or somatosensory inputs over vestibular ones.1 This mismatch, along with reduced cortical integration of spatial orientation, results in inaccurate perception of impaired posture or balance. The misunderstanding is compounded by heightened attention to moving or complex visual stimuli and by increased sensitivity to self and/or object motion.2 This leads to suboptimal postural and gait strategies, such as a stiffened walk and shorter strides, in adapting to a past postural threat.2,8 The discrepancy between anticipated and actual afferent input, overreliance on vision for balance, hypervigilance to balance sensations, and increased anxiety create a reinforcing cycle of chronic functional dizziness.9

Neuroimaging. Patients experiencing PPPD display decreased brain structure, function, and connectivity in areas involved in multisensory vestibular processing and spatial cognition, but increased function and connectivity in visual processing regions.10 Reduced gray matter volume is noted in the left superior temporal gyrus, bilateral middle temporal gyrus, left middle temporal visual area, bilateral cerebellum, left-sided posterior hippocampus, right precentral gyrus, left anterior cingulate gyrus, left caudate nucleus, and left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.2

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) reveals heightened activity in the visual cortex. However, there is reduced resting-state connectivity between the hippocampi, right inferior frontal gyrus, bilateral temporal lobes, bilateral insular cortices, bilateral central opercular cortices, left parietal opercular cortex, bilateral occipital lobes, cerebellum, temporal lobes, right amygdala, and right interior frontal gyrus to right orbitofrontal cortex, and between the cerebellum to the left caudate, left nucleus accumbens, and bilateral precentral gyri (primary motor cortex).2

These morphometric and functional differences support the hypothesis that PPPD arises from interactions among visuo-vestibular, sensorimotor, and emotional networks.11 Such interactions favor visual over vestibular inputs and support anxiety-mediated changes to locomotor control.11 Increased connectivity within visuo-motor systems may reflect abnormal postural control and balance strategies for ensuring safety, but they paradoxically inhibit optimal posture.11

Causation conclusions are not possible due to the small sample size of neuroimaging studies and because such changes are also observed in patients with peripheral vestibular lesions or pre-existing psychiatric conditions that affect brain functioning.10 Anxiety exacerbates space and motion discomfort; this is likely to be mediated by shared neural pathways that process visuo-vestibular and emotional stimuli.12 Some people with PPPD experience diminished pain habituation in response to painful stimuli, suggesting that pathogenesis may involve an increased response to painful or distressing stimuli apart from vestibular/visual inputs.13 Some patients with PPPD have more carotid atherosclerosis, white matter hyperintensities, and lacunar infarctions, which may be risk factors for developing PPPD.14

Psychopathology. Anxiety, depression, and obsessive personality traits are common features in people with PPV.15 Neuroticism, introversion, obsessive compulsive personality disorder (OCPD) traits, and a family history of anxiety confer increased risk of developing PPPD.1 Many persons with PPPD might deny nervousness, yet display anxiety during postural tasks.2 Subjects with PPPD reported greater anxiety, but equivalent depression, compared to patients with other vestibular pathology.16 When prospectively compared to individuals who recovered from vestibular symptoms, those with PPPD reported greater anxiety and depression; the severity of anxiety was correlated to illness duration.6 This describes a cycle where being anxious predisposes one to developing PPPD, which in turn worsens anxiety.6 Despite the association, it is unclear whether individuals with pre-existing mood and anxiety disorders are more likely to develop PPPD, or whether those with PPPD develop secondary mood and anxiety disorders.

It is difficult to establish causality between psychological disorders and PPPD, as patients with depression, generalized anxiety disorder, agoraphobia, social phobia, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), and trauma-related conditions may report persistent dizziness but do not meet criteria for PPPD.1 Furthermore, traumas and/or other adverse life events are equally represented in persons with structural vestibular syndromes.1

Treatment of PPPD

The most common treatment outcome is reduction, rather than elimination, of symptoms.17 Early multimodal treatment significantly reduces symptoms and improves prognoses; it includes patient education, vestibular rehabilitation, and psychiatric interventions, namely cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and pharmacotherapy.9

Studies of group-delivered CBT and pharmacotherapy reduced severity of PPPD symptoms and associated anxiety and depression (Tables 1 and 2). Primary outcome measures included the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI), Vertigo Symptom Scale (VSS), Spielberger Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Confidence in Everyday Activities (CEA), Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), Vertigo Handicap Questionnaire (VHQ), Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS), Dizziness Symptom Inventory (DSI), Safety Behaviors Inventory (SBI), Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21), Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HARS), Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HDRS), Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement (CGI-I), Brief Symptom Inventory-53 (BSI-53), Zung Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), and an author-created dizziness and unsteadiness questionnaire.18–33 When available, the incidence of any comorbid psychiatric illnesses is documented.

Psychotherapy. Nine elderly subjects reported less dizziness, but no diminished anxiety or depression, when CBT techniques (i.e., applied relaxation, graded exposure, and psychoeducation) were added to VR.34 In a later study, 29 adults aged 18 to 64 years with dizziness were assessed while receiving either VR or VR combined with small-group CBT (applied relaxation and exposure techniques). Participants receiving cotherapy reported attenuation in dizziness but not anxiety or depression.35

In a randomized study, all 36 subjects with PPV received condition-related education and self-directed vestibular rehabilitation exercises, but the treatment group also received adjunctive CBT. In contrast to earlier studies, both groups reported decreased vertigo and handicap, yet those receiving adjunctive therapy described reduction in anxiety and depression too.36 These improvements deteriorated to pretreatment baseline at a one-year reassessment.37

Forty-one patients with CSD were randomized to receive CBT for dizziness (adapted from panic disorder) or waited for four weeks before starting CBT.26 The two primary outcome measures, DSI and SBI, were developed by the authors for this study and demonstrated good internal consistency. CBT consisted of psychoeducation, behavioral experiments, identifying avoidance/safety behaviors, demonstrating alternative strategies, and focusing on life activities rather than symptom resolution. Sixteen participants met criteria for generalized anxiety, 16 for major depression, 15 for panic disorder, two for dysthymia, and one for social phobia. The treatment subjects reported 75-percent decreased dizziness and heightened social engagement but denied less anxiety or depression. At six-month follow-up, most of them described sustained, but not continuous, attenuation of dizziness and disability. Nevertheless, 18 percent of patients had deteriorated and no longer met criteria for the significant improvement they had achieved immediately posttreatment.38

Seventeen patients were offered “psychotherapeutic interventions” to counteract “somatoform vertigo and dizziness.”39 Interventions included psychoeducation, exposure to dizzying situations, analyzing resources and abilities, and modifying coping strategies. While not formal CBT, the intervention mitigated psychological stress and improved postural control measured by posturography.39

In randomized research to evaluate the effect of augmenting sertraline pharmacotherapy with CBT, all 91 subjects were prescribed sertraline 50 to 200mg/day, while the experiment group also received twice-weekly CBT.40 Although everyone indicated diminished dizziness, depression, and anxiety, those also receiving CBT experienced a better response; they benefited from lower doses of sertraline and experienced fewer medication adverse effects.40

A telephone survey was given to 33 patients to learn more about the condition “using principles of CBT.”41 Twenty-one participants reported concurrent mental illness: 14 had anxiety, 12 reported depression, and one had anorexia nervosa. Out of 26 subjects, five fully recovered, 10 had some improvement, and 11 got no better. Although half of them took antidepressant drugs, this did not influence outcomes.41

In a retrospective study of 150 patients with PPPD who received CBT, 100 of them had received various antidepressant medications, and 63 reported an unspecified anxiety disorder or posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).17 CBT included listing avoidance behaviors, behavioral activities for distraction, and practicing mindfulness or relaxation techniques. The CBT subject group had less dizziness, anxiety, and/or depression.17

Pharmacotherapy. One study of 60 patients aged 13 to 81 years with idiopathic dizziness, psychogenic dizziness, or dizziness due to neuro-otologic condition with psychiatric symptoms received a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) drug titrated to efficacy, adverse effects, or lack of response after 20 weeks.42 No psychological intervention was provided. Among the subjects, 38 were much and/or very much improved; however, 15 of them discontinued treatment due to side effects. There was no difference in efficacy or adverse consequences among medications. Among those 38 people with improvement, 28 were observed for at least another year, and all but two evidenced continued progress. Shorter illness duration was associated with greater improvement.42

Twenty patients with CSD received sertraline titrated to efficacy, adverse effects, or a maximum dose of 200mg/day (median dose: 100mg/day); additional pharmacotherapy or psychotherapy were not administered.43 All subjects reported depression, eight reported panic disorder, six had generalized anxiety, and two had OCD. Five persons discontinued the study due to adverse effects, although 11 of the remaining participants had less dizziness, and six indicated complete symptom resolution.43

Forty-seven subjects with either organic or psychogenic dizziness received paroxetine 20mg/day.44 Four of them discontinued pharmacotherapy due to adverse effects. Although all patients reported less dizziness, improvement was most pronounced for those with severe depression, which also improved.44

Eighty-eight people with different CSD subtypes and a concurrent anxiety disorder were randomized to receive various SSRIs.45 CSD was classified as primary otologic, primary psychogenic, or interactive (pre-existing anxiety exacerbated by chronic dizziness following neurotologic illness). The subjects affected with otogenic and psychogenic subtypes evidenced reductions in dizziness and anxiety, but less response was documented in those with interactive-type dizziness; the diminished response was attributed to illness chronicity.45

While efficacy data is limited for serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRI), milnacipran (unknown details) mitigated dizziness and anxiety.46 A comparison trial of milnacipran 50mg/day and fluvoxamine 200mg/day induced similar reductions in anxiety, depression, and dizziness in 29 patients.47 Venlafaxine also diminished CSD symptoms in 32 patients with vestibular migraine.48

Other antidepressant drugs, such as mirtazapine and tricyclic antidepressants, are prescribed to individuals with PPPD, but their efficacy has not been assessed.49 Benzodiazepines and vestibular suppressants, such as meclizine or prochlorperazine, can be helpful in the acute phase of a vestibular disorder, but they are not effective long-term or as monotherapies for CSD and may perpetuate symptoms.49,50

Neuromodulation. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex appears ineffective for PPPD. In an open-label, five-day pilot study, eight patients received five tDCS treatments and experienced only transient reduction in dizziness during the treatment period.51 In a randomized, three-week trial, 24 subjects received 15 sessions of active or sham tDCS, with neither group reporting less dizziness.52

Recommendations

Patients sometimes have antagonistic or fearful beliefs about their PPPD symptoms and prognosis.17 Psychotherapy should include psychoeducation that symptoms are part of abnormal sensory processing and postural control, which occur in response to a past stressor or vestibular disorder. Although maladaptive beliefs and posture developed, these can be modified. Full symptom remission might not occur, yet there is hope for improvement.17 The absence of comorbid anxiety is a predictive factor for improvement after six months of receiving multimodal treatment.53

How serotonergic medications improve PPPD symptoms is unknown, although they attenuate the anxiety and depression so often observed in people with PPPD.8 These pharmaceuticals may directly affect the vestibular nuclear complex, which is related to motion-sensitive neural pathways.54 Investigators initiated smaller doses (25–50% of the conventional starting dose for depression) and later titrated to efficacy or adverse effects; higher doses were prescribed for severe psychiatric comorbidity.49 Cisgender female sex, younger age, and mild disease severity predict better responses to serotonergic pharmacotherapy.55 Consider and screen for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) and PPPD when someone presents with either condition; one survey of 25 patients revealed a high prevalence of OSA among those with PPPD.56

Conclusion

PPPD is a functional neurological disorder characterized by dizziness, unsteadiness, and/or vertigo. Anxiety and depression are frequent accompanying psychiatric diagnoses, but a causal relationship with PPPD is unclear. Early intervention with psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapies, particularly SSRIs, may reduce psychiatric symptoms and improve prognoses.

References

- Staab JP, Eckhardt-Henn A, Horii A, et al. Diagnostic criteria for persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): consensus document of the committee for the Classification of Vestibular Disorders of the Bárány Society. J Vestib Res. 2017;27(4):191–208.

- Castro P, Bancroft MJ, Arshad Q, Kaski D. Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD) from brain imaging to behaviour and perception. Brain Sci. 2022;12(6):753.

- Yagi C, Morita Y, Kitazawa M, et al. Subtypes of persistent postural-perceptual dizziness. Front Neurol. 2021;12:652366.

- Bigelow RT, Semenov YR, du Lac S, et al. Vestibular vertigo and comorbid cognitive and psychiatric impairment: the 2008 National Health Interview Survey. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(4):367–372.

- Nazareth I, Yardley L, Owen N, et al. Outcome of symptoms of dizziness in a general practice community sample. Fam Pract. 1999;16(6):616–618.

- Teh CS, Prepageran N. The impact of disease duration in persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD) on the quality of life, dizziness handicap and mental health. J Vestib Res. 2022;32(4):373–380.

- Popkirov S, Staab JP, Stone J. Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD): a common, characteristic and treatable cause of chronic dizziness. Pract Neurol. 2018;18(1):5–13.

- Staab JP. Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness. Semin Neurol. 2020;40(1):130–137.

- Kaski D. Neurological update: dizziness. J Neurol. 2020;267(6):1864–1869.

- Im JJ, Na S, Jeong H, Chung YA. A review of neuroimaging studies in persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD). Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;55(2):53–60.

- Indovina I, Passamonti L, Mucci V, et al. Brain correlates of persistent postural-perceptual dizziness: a review of neuroimaging studies. J Clin Med. 2021;10(18):4274.

- Redfern MS, Furman JM, Jacob RG. Visually induced postural sway in anxiety disorders. J Anxiety Disord. 2007;21(5):704–716.

- Holle D, Schulte-Steinberg B, Wurthmann S, et al. Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness: a matter of higher, central dysfunction? PLoS One. 2015;10:e0142468.

- Li L, He S, Liu H, et al. Potential risk factors of persistent postural-perceptual dizziness: a pilot study. J Neurol. 2022;269(6):3075–3085.

- Brandt T. Phobic postural vertigo. Neurology. 1996;46(6):1515–1519.

- Maslovara S, Begic D, Butkovic-Soldo S, et al. Are the persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD) patients more anxious than the patients with other dizziness? Psychiatr Danub. 2022;34(1):71–78.

- Waterston J, Chen L, Mahony K, et al. Persistent postural-perceptual dizziness: precipitating conditions, co-morbidities and treatment with cognitive behavioral therapy. Front Neurol. 2021;12:795516.

- Jacobson GP, Newman CW. The development of the dizziness handicap inventory. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1990;116(4):424–427.

- Yardley L, Masson E, Verschuur C, et al. Symptoms, anxiety and handicap in dizzy patients: development of the vertigo symptom scale. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36(8):731–741.

- Spielberger CD. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y). Consulting Psychologists Press; 1983.

- Beck A, Ward C, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961(4):561–571.

- Hallam RS, Hinchcliffe R. Emotional stability; its relationship to confidence in maintaining balance. J Psychosom Res. 1991;35(4–5):421–430.

- Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396.

- Yardley L, Putman J. Quantitative analysis of factors contributing to handicap and distress in vertiginous patients: a questionnaire study. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1992;17(3):231–236.

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67(6):361–370.

- Edelman S, Mahoney AE, Cremer PD. Cognitive behavior therapy for chronic subjective dizziness: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Otolaryngol. 2012;33(4):395–401.

- Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales, 2nd edition. Psychology Foundation of Australia; 1995.

- Hamilton M. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32(1):50–55.

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23(1):56–62.

- Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare Public Health Service Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration; 1976.

- Derogatis LR, Melisaratos N. The Brief Symptom Inventory: an introductory report. Psychol Med. 1983;13(3):595–605.

- Nishiike S, Takeda N, Koizuka I, et al. Multivariate analysis of everyday handicap of patients with dizziness. Jpn J Otorhinolaryngol. 1995;98(1):31–40. Japanese.

- Zung WW. A self-rating depression scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1965;12:63–70.

- Johansson M, Akerlund D, Larsen HC, Andersson G. Randomised controlled trial of vestibular rehabilitation combined with cognitive behaviour therapy for dizziness in older people. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125(3):151–156.

- Andersson G, Asmundson GJ, Denev J, et al. A controlled trial of cognitive behaviour therapy with vestibular rehabilitation in the treatment of dizziness. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(9):1265–1273.

- Holmberg J, Karlberg M, Harlacher U, et al. Treatment of phobic postural vertigo. A controlled study of cognitive-behavioral therapy and self-controlled desensitization. J Neurol. 2006;253(4):500–506.

- Holmberg J, Karlberg M, Harlacher U, et al. One-year follow-up of cognitive behavioral therapy for phobic postural vertigo. J Neurol. 2007;254(9):1189–1192.

- Mahoney AEJ, Edelman S, Cremer PD. Cognitive behavior therapy for chronic subjective dizziness: longer-term gains and predictors of disability. Am J Otolaryngol. 2013;34(2):115–120.

- Best C, Tschan R, Stieber N, et al. STEADFAST: psychotherapeutic intervention improves postural strategy of somatoform vertigo and dizziness. Behav Neurol. 2015;2015:456850.

- Yu YC, Xue H, Zhang YX, Zhou J. Cognitive behavior therapy as augmentation for sertraline in treating patients with persistent postural-perceptual dizziness. Biomed Res Int. 2018; 2018:8518631.

- Ishizuka K, Shikino K, Yamauchi Y, et al. The clinical key features of persistent postural perceptual dizziness in the general medicine outpatient setting: a case series study of 33 patients. Intern Med. 2020;59(22):2857–2862.

- Staab JP, Ruckenstein MJ, Solomon D, Shepard NT. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors for dizziness with psychiatric symptoms. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128(5):554–560.

- Staab JP, Ruckenstein MJ, Amsterdam JD. A prospective trial of sertraline for chronic subjective dizziness. Laryngoscope. 2004;114(9):1637–1641.

- Horii A, Mitani K, Kitahara T, et al. Paroxetine, a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, reduces depressive symptoms and subjective handicaps in patients with dizziness. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25(4):536–543.

- Staab JP, Ruckenstein MJ. Chronic dizziness and anxiety: effect of course of illness on treatment outcome. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;131(8):675–679.

- Horii A, Kitahara T, Masumura C, et al. Effects of milnacipran, a serotonin noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) on subjective handicaps and posturography in dizzy patients. Abstract presented at the Twenty-fifth Congress of the Barany Society, April 2008; Kyoto, Japan.

- Horii A, Imai T, Kitahara T, et al. Psychiatric comorbidities and use of milnacipran in patients with chronic dizziness. J Vestib Res. 2016;26(3):335–340.

- Staab JP. Clinical clues to a dizzying headache. J Vest Res. 2011;21(6):331–340.

- Staab JP. Chronic subjective dizziness. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2012;18(5 Neuro-otology):1118–1141.

- Whalley MG. A cognitive-behavioral model of persistent postural-perceptual dizziness. Cogn Behav Pract. 2017;24(1):72–89.

- Palm U, Kirsch V, Kübler H, et al. Transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) for treatment of phobic postural vertigo: an open label pilot study. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2019;269(2):269–272.

- Im JJ, Na S, Kang S, et al. A randomized, double-blind, sham-controlled trial of transcranial direct current stimulation for the treatment of persistent postural-perceptual dizziness (PPPD). Front Neurol. 2022;13:868976.

- Toshishige Y, Kondo M, Kabaya K, et al. Cognitive-behavioural therapy for chronic subjective dizziness: predictors of improvement in Dizziness Handicap Inventory at 6 months posttreatment. Acta Otolaryngol. 2020;140(10):827–832.

- Soto E, Vega R, Seseña E. Neuropharmacological basis of vestibular system disorder treatment. J Vestib Res. 2013;23(3):119–137.

- Min S, Kim JS, Park HY. Predictors of treatment response to pharmacotherapy in patients with persistent postural-perceptual dizziness. J Neurol. 2021;268(7):2523–2532.

- Bery AK, Azzi JL, Le A, et al. Association between obstructive sleep apnea and persistent postural-perceptual dizziness. J Vestib Res. 2021;31(5):401–406.