by Sittichai Khamsai, MD; Kathleen Howe, MSc; Pewpan M. Intapan, MD; Wanchai Maleewong, PhD; Verajit Chotmongkol, MD; and Kittisak Sawanyawisuth, MD, PhD

by Sittichai Khamsai, MD; Kathleen Howe, MSc; Pewpan M. Intapan, MD; Wanchai Maleewong, PhD; Verajit Chotmongkol, MD; and Kittisak Sawanyawisuth, MD, PhD

Drs. Khamsai, Chotmongkol, and Sawanyawisuth are with the Department of Medicine at Khon Kaen University in Khon Kaen, Thailand. Drs. Intapan and Maleewong are with the Department of Parasitology at Khon Kaen University in Khon Kaen, Thailand.

FUNDING: This study was supported by the Thailand Research Fund’s Distinguished Research Professor Grant (Grant no. DPG6280002; awarded to Pewpan Maleewong Intapan and Wanchai Maleewong).

DISCLOSURES: The author has no conflict of interest relevant to the content of the article.

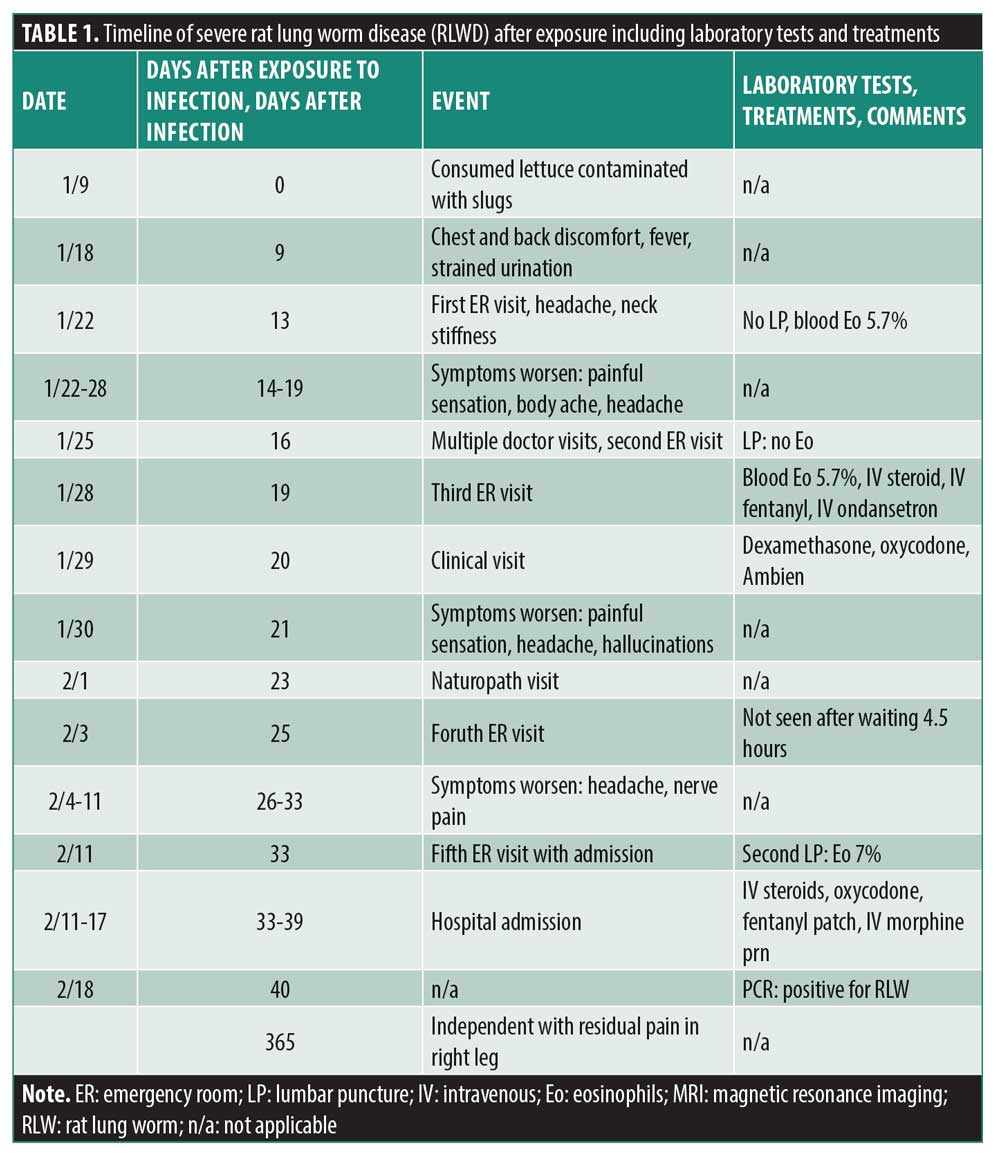

ABSTRACT: Severe rat lung worm disease (RLWD) is an uncommon condition, but it can result in severe complications and can be difficult to diagnose, necessitating awareness on the part of physicians everywhere. We review the clinical manifestations and diagnostic dilemmas of severe RLWD based on a case in Hawaii. A 50-year-old man developed mild headache, a burning sensation in the limbs, fever, and strained urination nine days after consuming lettuce contaminated with parasitic nematodes (Angiostrongylus cantonensis [A. cantonensis]). In time, his headache became more severe, and he developed purple semi-circular stripes at the base of nail beds. He sought medical attention, but the diagnosis was delayed, likely due to unfamiliarity with the condition by the initial treating clinician. The diagnosis was eventually based on evidence of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), eosinophils, and positive polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of CSF for A. cantonensis. Corticosteroid treatment was delayed, and albendazole was not administered due to a lack of availability. A greater awareness of RLWD on the part of physicians may have prevented these delays.

Keywords: Angiostrongylus cantonensis, eosinophilic meningitis, slugs

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2021;18(4–6):xx–xx

Eosinophilic meningoencephalitis (EME) is caused by the parasitic nematode Angiostrongylus cantonensis (A. cantonensis) and can lead to significant morbidity and mortality. EME is one form of rat lung worm disease (RLWD) and may involve other organs, including the eyes and spinal cord.1-3 Although there have been thousands of cases of RLWD worldwide,4 there have been few published case reports. Here, we report the case of severe RLWD, focusing on its unusual presentation, treatment options, and importance of physician awareness of the disease.

Case Story

A previously healthy 50-year-old American man presented with chest and back discomfort that began four days prior. Nine days before developing symptoms, he had eaten lettuce from his garden that was contaminated with hundreds of parasitic nematodes. He had rinsed and spun the lettuce in a salad spinner before eating it, but after having already taken several bites, he discovered a live adult slug on his plate. After noticing this, he forced vomiting. Other than chest and upper- to middle-back tightness, he also experienced fitful sleep with restless legs; tingling in the tip of his right thumb; mild headache; tingling/burning in the neck, toes, feet, and hands; fever; strained urination; sore calves; shooting pain in the legs; trouble walking; hiccups for multiple days; night sweats; and cold feet.

At the emergency room (ER), 13 days after exposure to infection, he suggested to the doctor that he might have RLWD, but was informed that the only way to detect RLWD would be through lumbar puncture (LP). Although a complete blood count revealed an eosinophil level of 5.7 percent, the LP was not recommended by the attending physician. The patient was discharged with gabapentin, ibuprofen, and a muscle relaxant.

After the ER visit, 14 days after infection, he developed new symptoms and his previous symptoms worsened. The tingling/burning had become more painful, which he described as feeling like a cheese grater over the skin that made wearing clothing uncomfortable. He also developed light tremors, loss of agility, and swelling and pain in his hands; his body aches and headaches became more severe. He also began experiencing neck stiffness, shooting pain in various spots throughout his body, lethargy, and malaise, as well as purple semi-circular stripes at the base of the nail beds (most prominent on the thumbs).

He visited several doctors, which included a second ER visit 16 days after infection. At the ER, the emergency physician reluctantly performed an LP, as the patient and his wife insisted that he may have RLWD. No blood test was performed, and there was no evidence of eosinophils in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). He was discharged without medication and informed that he did not have RLWD.

Three days later, he began vomiting and shaking. He visited the ER for the third time, during which it was found that his blood eosinophils had risen from 5.7 percent to 7.4 percent, with elevated serum protein. Now recognizing the possibility of RLWD, the emergency physician initiated treatment with intravenous steroids, intravenous fentanyl, and intravenous ondansetron. After treatment, the patient felt better for the first time since his illness had begun. The emergency physician advised him to see an RLWD expert in Hawaii, but the expert did not agree to see him for unknown reasons. The patient did receive a call back from another RLWD expert (20 days after infection) who agreed to see him. After a complete examination, the patient received dexamethasone, oxycodone, and zolpidem and was scheduled for weekly visits as part of his outpatient care. His symptoms subsequently worsened (21 days after infection) despite treatment. He experienced new shooting/burning pain in different parts of his body with sensitivity to touch. His headaches intensified, he developed nausea, and his vision became slightly blurred. He also became sensitive to light and sound and had cognitive impairment, including inability to order his thoughts, mixing up dreams with hallucinations, stuttering, and short-term memory loss. After consulting with the RLWD expert, he attempted to attain albendazole, but it was not available at his pharmacy. He received 11 intravenous treatments from a naturopathic doctor, which consisted of 25 to 50mg of vitamin C, Myers Cocktail with a 1,000mg glutathione push, phosphatidylcholine with a 1,000mg glutathione push, and ozone treatment. However, his symptoms persisted. Two days later, he returned to the ER for the fourth time hoping to receive intravenous steroid and albendazole treatment. After waiting for 4.5 hours, he left the ER without having been seen.

A week later, 26 to 32 days after infection, his symptoms had worsened. He became bedridden, could not work, could not drink or eat, and could not move his head. He also had severe headaches, with nerve pain in his right leg and arm. Due to his severe nerve pain, at his next outpatient visit he was sent to the ER for the fifth time in three weeks (33 days after infection). A second LP was performed, showing 7 percent eosinophils in his CSF. He was admitted and received intravenous steroids and drugs for pain, including intravenous morphine, fentanyl patch, and oral oxycodone. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a microhemorrhage in the left side of the brain. He was admitted for six days and lost 20 pounds. After discharge (40 days after infection), a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test of his CSF came back positive for A. cantonensis. This was the second case of RLWD reported in the Hawaiian public health registry in 2019.

Discussion

There are several important lessons for healthcare providers in this report. The first is the extent of physical and mental suffering the patient experienced and how these were exacerbated by inappropriate management. This patient had a very severe case of RLWD and was fortunate to have survived, despite delayed diagnosis and management. In Thailand, the reported mortality rate of severe RLWD is as high as 80 percent.5 In addition, this patient had to struggle with his physicians to receive proper treatment. The attending physicians lacked the knowledge to properly treat RLWD, as demonstrated by their unwillingness to listen to the patient regarding his illness. The patient should have undergone an LP when it was first requested.

Another important finding was that the patient experienced several symptoms that are not common or have never been reported in RLWD, including chest tightness, cough, hiccups, and purple semi-circular stripes at the base of the nail beds. The chest tightness and hiccups may be explained by the larvae returning to the pulmonary artery.2, 3 However, these symptoms occurred sooner than usual, with the chest tightness appearing at about nine days after infection. Strained urination, photophobia, psychosis, and gastrointestinal disturbance are also uncommon symptoms of RLWD.6-8 In addition, the nail abnormalities described here have never been reported in RLWD.4

Although the presenting symptom of chest and back discomfort is not a common leading symptom of RLWD, the patient had obvious larval exposure within the possible incubation period. The incubation period can range from one day to several months but is usually within three months.9 Headache is the most common presenting symptom, but that is for eosinophilic meningitis particularly in Thailand and East Asia.9

In addition to history of larva exposure, this patient showed signs suggestive of RLWD: hyperesthesia or paresthesia not related with nerve distribution2, 3 and neck stiffness. Although neck stiffness had not yet occurred by the patient’s first ER visit, this kind of delay is common. Only half of patients with RLWD experience neck stiffness by the first doctor visit.9 Fever is another sign of severe RLWD,10 occurring 37 times more often than in less severe cases.

It is also important to note the issues the patient experienced regarding diagnosis in this case. RLWD can be easily missed or underdiagnosed, particularly if the attending physician is not knowledgeable about the condition. In this case the emergency physician mistakenly informed the patient that an LP was the only way to diagnose RLWD. In addition, clinical evidence of meningitis is rare in RLWD, with only 10 percent of adult patients with meningitis experiencing fever and only half with neck stiffness.9 This demonstrates that diagnosis of RLWD cannot rely solely on physical signs. Important clues for RLWD are history of larva exposure within three months and neurological symptoms (commonly headache).3 Screening for peripheral eosinophilia is a useful tool in RLWD diagnosis. An absolute eosinophil count of more than 798 cells or eosinophil levels over nine percent have been found to indicate RLWD, with sensitivities of 76.6 percent and 74.5 percent, respectively.11 Note that results of this test should be considered along with history of larva exposure, and that RLWD cannot be ruled out solely due to the absence of eosinophilia. PCR and immunoblotting can also be used to detect RLWD.3

Physicians should also note that LP with evidence of CSF eosinophils is suggestive of RLWD if there is no other cause of CSF eosinophils and there is history of larva exposure.3 In this patient, the first LP showed no evidence of CSF eosinophils, and the amount found on the second did not reach the diagnostic criterion. This implies that CSF eosinophilia should not be used as a stand-alone diagnostic tool. Assuming the first LP result was not an error, this suggests that other laboratory tests may be needed to diagnose RLWD, such as immunoblotting or PCR, particularly in patients with history of larva exposure3 or who are otherwise highly clinically suspicious. It is also likely that the EME diagnostic criterion should be lowered to any percentage of CSF eosinophils.12,13 A previous study found that nine out of 17 patients with RLWD had CSF eosinophil levels of less than 10 percent, five of whom had no CSF eosinophils.13 In addition to being a diagnostic tool, LP helps to significantly reduce headaches in patients with RLWD. It can be performed repeatedly as needed and has been shown to reduce the severity of headaches by 63.29 percent.14 However, there is no evidence of repeated LP preventing severe RLWD.

Patients with severe RLWD may also have normal MRI results. A previous study reported normal MRI results in 45 percent of patients with RLWD and only nodular lesions may be found in EME.15 This suggests that MRI abnormalities may not be related to clinical features. The patient in our report may have had predominantly spinal involvement, as evidenced by presence of severe limb pain.16

This case also provides some clinical lessons. As mentioned, the patient had both typical and atypical presentations of RLWD in addition to history of direct larva exposure prior to the development of symptoms.17 Albendazole is a potentially effective treatment for RLWD and should be administered as soon as possible (but not later than three weeks after exposure). Despite the patient actively seeking medical assistance from various sources, diagnosis was delayed, likely due to unfamiliarity by the treating clinicians with the disease. As a result, treatment was similarly delayed, which could have resulted in greater neurological damage and more long-term complications.

There are several issues raised by this case that merit further research. First, the effect of albendazole treatment after larva exposure but before the onset of neurological symptoms should be examined.17 Second, there has been no study on the effects of repeated LP procedures or supplementation in the prevention or treatment of severe RLWD. Third, studies should be conducted to determine risk factors or predictors of severe RLWD in countries outside Thailand. Finally, alternatives to albendazole should be examined, as it is not widely available in the US.

Summary

This report highlights several concerns and observations regarding severe RLWD, including its uncommon presentations in one patient, the issue of underdiagnosis and lack of general knowledge of the disease among US physicians, and the potential usefulness of a new clinical criterion of increased CSF eosinophils. Clinicians should be aware of RLWD, particularly in endemic areas or in patients who have recently visited such areas.

References

- Chotmongkol V, Yimtae K, Intapan PM. Angiostrongylus eosinophilic meningitis associated with sensorineural hearing loss. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118(1):57–58.

- Monteiro MD, de Carvalho Neto EG, Dos Santos IP, et al. Eosinophilic meningitis outbreak related to religious practice. Parasitol Int. 2020;78:102158.

- Sawanyawisuth K, Chotmongkol V. Eosinophilic meningitis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2013;114:207–215.

- Wang QP, Lai DH, Zhu XQ, Chen XG, Lun ZR. Human angiostrongyliasis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8(10):621-630.

- Chotmongkol V, Sawanyawisuth K. Clinical manifestations and outcome of patients with severe eosinophilic meningoencephalitis presumably caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2002;33(2):231–234.

- Hong DS, Bernstein M, Smith C, Gans H, Shaw RJ. Eosinophilic meningoencephalitis: psychiatric presentation and treatment. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2008;38(3):287–295.

- Hsueh CW, Chen HS, Li CH, Chen YW. Eosinophilic meningitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis in an adolescent with mental retardation and pica disorder. Pediatr Neonatol. 2013;54(1):56–59.

- Malvy D, Ezzedine K, Receveur MC, et al. Cluster of eosinophilic meningitis attributable to Angiostrongylus cantonensis infection in French policemen troop returning from the Pacific Islands. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2008;6(5):301–304.

- Khamsai S, Chindaprasirt J, Chotmongkol V, et al. Clinical features of eosinophilic meningitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis in Thailand: a systematic review. Asia Pac J Sci Technol. 2020;25(2):APST-25-02-09.

- Sawanyawisuth K, Takahashi K, Hoshuyama T, et al. Clinical factors predictive of encephalitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;81(4):698–701.

- Sawanyawisuth K, Sawanyawisuth K, Senthong V, et al. Peripheral eosinophilia as an indicator of meningitic angiostrongyliasis in exposed individuals. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2010;105(7):942–924.

- Slom TJ, Cortese MM, Gerber SI, et al. An outbreak of eosinophilic meningitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis in travelers returning from the Caribbean. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(9):668–675.

- Tsai HC, Liu YC, Kunin CM, et al. Eosinophilic meningitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis: report of 17 cases. Am J Med. 2001;111(2):109–114.

- Sawanyawisuth K, Limpawattana P, Busaracome P, et al. A 1-week course of corticosteroids in the treatment of eosinophilic meningitis. Am J Med. 2004;117(10):802–803.

- Jin EH, Ma Q, Ma DQ, He W, Ji AP, Yin CH. Magnetic resonance imaging of eosinophilic meningoencephalitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis following eating freshwater snails. Chin Med J (Engl). 2008;121(1):67–72.

- Maretić T, Perović M, Vince A, Lukas D, Dekumyoy P, Begovac J. Meningitis and radiculomyelitis caused by Angiostrongylus cantonensis. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15(6):996–998.

- Prociv P, Turner M. Neuroangiostrongyliasis: The “Subarachnoid Phase” and Its Implications for Anthelminthic Therapy. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2018;98(2):353–359.