by Michelle Stewart, PhD; Adam Butler; Larry Alphs, MD, PhD; Phillip B. Chappell, MD; Douglas E. Feltner, MD; William R. Lenderking, PhD; Atul R. Mahableshwarkar, MD; Clare W. Makumi, PharmD, MBA; Sarah Dubrava, MS; and the ISCTM Suicidal Ideation and Behavior Assessment Working Group

Dr. Stewart is Sr. Director, Outcomes Research, Specialty Care Medicines Development Group, Pfizer, Inc., Groton, Connecticut; Dr. Butler is with Bracket, Wayne, Pennsylvania; Dr. Alphs is Therapeutic Area Leader Psychiatry, Janssen Scientific Affairs, Princeton, New Jersey; Dr. Chappell is with Pfizer Inc., Groton, Connecticut, and Yale School of Medicine, Child Study Center, New Haven, Connecticut; Dr. Feltner is Douglas E. Feltner LLC, Novi, Michigan; Dr. Lenderking is with United Biosource Inc., Lexington, Massachusetts; Dr. Mahableshwarkar is with Takeda Global Research and Development Center, Inc., Deerfield, Illinois; Dr. Makumi is with GlaxoSmithKline, Research Park Triangle, North Carolina; and Ms. DuBrava is with Pfizer Inc., Groton, Connecticut.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(5–6 Suppl A):20S–28S

Funding: The ISCTM supported the implementation of the survey with staff time and funding.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Butler is an employee of Bracket in Wayne, Pennsylvania; Dr. Stewart is an employee of Pfizer Inc., in Groton, Connecticut; Dr. Alphs is an employee of Janssen Scientific Affairs in Princeton, New Jersey; Dr. Chappell is an employee of Pfizer Inc., in Groton, Connecticut; Dr. Feltner has no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article; Dr. Lenderking is an employee of United Biosource Inc. in Lexington, Massachusetts; Dr. Mahableshwarkar is an employee of Takeda Global Research and Development Center, Inc., in Deerfield, Illinois; Dr. Makumi is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline in Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, and Ms. DuBrava is an employee of Pfizer Inc., in Groton, Connecticut.

Key words: Suicidal ideation; suicidal behavior; clinical trials; survey; prospective assessment

Abstract: Objective: The International Society for CNS Clinical Trials and Methodology Suicidal Ideation and Behavior Assessment Working Group conducted an online survey regarding clinical trial site experiences and attitudes toward suicidal ideation and behavior data collection following the 2010 release of the initial United States Food and Drug Administration draft guidance on prospective assessment of suicidal ideation and behavior in clinical trials. Sites that had participated in at least one central nervous system clinical trial in the prior two years (N=6,058) were invited, via email, to complete a 20-item online assessment survey.

Results: Nine hundred and seventy-nine evaluable responses were collected (42% United States). Respondents included principal investigators (36%), raters (28%), coordinators (25%), and others (10%). The majority were psychiatrists (43%) and reported using suicidal ideation and behavior assessments across many indications. Most respondents (80%) personally conducted suicidal ideation and behavior assessments. Overall, respondents indicated that suicidal ideation and behavior assessments were readily incorporated into the conduct of clinical trials and improved subject safety. The greatest challenge was obtaining an accurate baseline lifetime history (51%), while the greatest benefit was identifying subjects at risk of suicide (84%). Approximately a quarter of respondents reported implementation challenges such as training. Differences based on geographical region, respondents’ roles, and responsibility for assessments were observed. Open-ended responses revealed additional challenges, e.g., use in cognitively impaired populations.

Conclusion: Prospective suicidal ideation and behavior monitoring was generally viewed positively, though specific challenges were identified. Limitations include self-report survey methodology and recruitment of only central nervous system clinical trials sites. These findings may help guide development of better methodologies for suicidal ideation and behavior assessment in clinical trials.

Introduction

In September 2010, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released a draft guidance requiring the prospective assessment of suicidal ideation and behavior (SIB) in clinical trials of central nervous system (CNS) active compounds. The draft guidance was subsequently updated in October of 2012. The guidance was directed toward SIB data collection in both psychiatric and nonpsychiatric indications and in neurological indications.[1] It was an outgrowth of increasing concerns regarding possible treatment-emergent SIB in clinical trials of antidepressant and antiepileptic medications in children and adults.[2–4] The research prompting these concerns was based largely on meta-analyses of data from clinical trials in which SIB was assessed retrospectively, using spontaneously reported adverse events. The studies included in the meta-analyses were not designed to prospectively identify SIB and did not include standardized assessments of SIB. Data identified by this retrospective review were classified by a blinded expert panel using the Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA).[5]

To address the limitations and bias inherent in retrospectively acquired data (i.e., incomplete case descriptions, poorly defined baseline status, missing cases), the draft guidance requires that data on SIB be prospectively collected by systematically querying subjects throughout a clinical trial. The stated purpose of the guidance is to ensure that patients who experience SIB in clinical trials are identified and receive appropriate care. Additionally, it was anticipated that this approach would provide more timely and complete SIB data, which would consistently code to the C-CASA categories, with less potential for bias.[1] Ultimately the data obtained would improve detection of SIB in individual studies and pooled analyses, with the expectation that these data would inform a product’s approved prescribing information.

The 2012 FDA draft guidance document recommends the use of an assessment instrument that maps potential suicide-related adverse events to an expanded set of C-CASA categories and specifically endorses the Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) as a tool to collect more timely and complete data on SIB, both as an aid to ensuring patient safety as well as facilitating the detection of problems in pooled analyses. The information collected with the C-SSRS can be mapped to the original C-CASA categories (see Gassmann-Mayer et al. for one approach[6]) as well as the expanded set of C-CASA categories outlined in the 2012 version. The guidance also allows for the use of alternative prospective assessment instruments provided they are shown to meet key criteria (e.g., including all the C-CASA concepts and mapping directly to the expanded set of categories) and have well-established psychometric properties.

Since the release of the first FDA draft guidance, SIB assessments have been widely implemented in clinical trials spanning multiple clinical indications, in diverse patient populations recruited from study centers in many different countries, regions, and cultures.[6–9] However, there has been little to no systematic investigation of the impact of this development on the clinical trial process and the logistical challenges associated with the inclusion of SIB assessments in global clinical trials.

The International Society for CNS Clinical Trials and Methodology (ISCTM) SIB Assessment Working Group was formed to evaluate current approaches to SIB data collection that has followed issuance of the FDA draft guidance. Participants in the SIB Assessment Working Group represent an array of stakeholders from clinical trials: investigators, raters, and other clinical trial site study staff; pharmaceutical sponsors; and vendors who support these studies. All members of this group have expertise in CNS drug development, encompassing a variety of therapeutic areas.

Based on their discussions, the SIB Assessment Working Group (WG) developed an anecdotal picture of the challenges and benefits associated with the implementation of the draft guidance. The current study was undertaken to move beyond anecdotal reports to obtain initial systematic data on the impact of the inclusion of SIB assessments on clinical research sites, particularly sites involved in CNS trials.

METHODS

Overview. The potential benefits identified anecdotally through discussion with stakeholders included enhanced patient safety, reduction of bias in the ascertainment of safety signals, and more informative drug labeling. Potential challenges included scale version control, availability of appropriately validated translations, incorporation of assessments into clinical visits, use in different cultures, and training of raters and sites with varying experience and familiarity with such assessments.

To better characterize the perceived benefits and challenges to implementation of SIB assessment, sites involved with SIB data collection were recruited to complete a brief internet-based survey.

Survey questionnaire development. A list of 20 survey items was generated after considering the WG’s initial list of potential site implementation issues. Five descriptive items elicited information regarding the site’s experience with trials in different therapeutic areas; the respondent’s training background, role at the site, and responsibility for conducting SIB assessments; and the site location (country). Twelve items were opinion items with five response categories (strongly agree, agree, neither agree/disagree, disagree, and strongly disagree). Two items listed benefits and challenges of implementing SIB assessments and asked respondents to mark all that applied. Respondents could also enter additional benefits or challenges not included in the survey. A final open-ended query invited respondents to add additional comments regarding SIB assessments at the site.

Sample identification. Sites were recruited using a list of e-mail addresses obtained from a contact database maintained by Bracket, Inc. A total of 6,058 study sites from around the globe that had participated in at least one CNS clinical trial in the prior two years were sent an email invitation with a link to the online survey.

Instructions accompanying the invitation encouraged respondents to speak with others at their site about their experiences implementing the assessment of SIB and to provide a single response from the site that reflected the site’s broader experience. Data were collected in July 2011 using the online survey software SurveyMonkey™.

Data analysis. Responses were summarized descriptively. Data were also summarized by subgroups of interest such as geographic region (US vs. other regions) and respondent characteristics, such as role at the site, training background, and responsibility for performing SIB assessments. Open-ended text responses were qualitatively reviewed and categorized to aid in summarizing.

RESULTS

Entire sample. A total of 1,004 responses (16.6% response rate) were collected over three weeks. Sites that reported conducting no trials using SIB assessments (N=25) were excluded from further analysis leaving a total evaluable sample of 979. Respondents reflected a wide cross-section of geographic regions with responses from 61 countries (Table 1). Slightly more than half (57.6%) were from outside the United States.

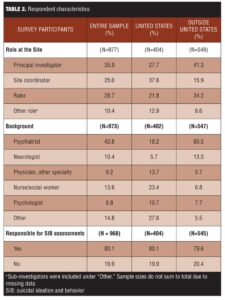

Principal investigators (PIs) represented the majority of respondents (35.9%), followed by rater (28.7%) and site-based study coordinators (25.0%). Respondents held a variety of roles at the sites and had diverse training backgrounds (Table 2). The majority (80.1%) had personally conducted prospective SIB assessments. In general, sites had extensive experience with SIB assessments, predominantly in CNS indications (Table 3).

Overall, respondents reported that incorporating prospective assessment of SIB has been beneficial to the conduct of clinical trials (Table 4). Respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statements “worth the additional burden” (72.6%), “easy to incorporate” (72.7%), and “improved subject safety” (74.0%). However, only 48.5 percent of the sample agreed or strongly agreed that the information obtained from SIB assessments is the most relevant for judging a subject’s suicide risk.

Tables 5 and 6 provide a breakdown of the important benefits and challenges endorsed, respectively. “Identifying subjects at risk of suicide” was the benefit most strongly endorsed (84.1%), while the greatest challenge identified was getting an accurate lifetime history at the baseline visit (51.1%).

One hundred sixteen (11.8%) respondents provided free-text comments about SIB assessment (Table 7). They included comments on particular scales (e.g., the C-SSRS), the need for more streamlined scales, and specific challenges to the use of these assessments, particularly in cognitively impaired populations.

Analysis by region. There were notable differences in role, background, and number of studies done by region (Table 2). Site coordinator was the role most commonly identified by respondents in the United States (37.6%), compared to only 15.9 percent of respondents outside of the United States. Respondents outside the United States were more likely than their United States counterparts to be primary investigators (PIs) (41.4% vs. 27.7%) or raters (34.2% vs. 21.8%). The proportion of respondents directly responsible for conducting assessments was similar between the United States and other regions: 81.0 percent versus 80.0 percent, respectively.

Respondents from outside the United States were more likely than United States respondents to be psychiatrists (60.5% vs. 18.2%, respectively) or neurologists (13.5% vs. 5.7%, respectively). United States respondents were more likely to report they were nurse/social workers (23.4% vs. 6.8%), a physician other than neurologist or psychiatrist (13.7% vs. 5.7%), or “other” (27.6% vs. 5.5%).

The differences in the number of studies sites had conducted in various therapeutic areas appeared to be related to differences in region (Table 3). Outside the United States, respondents had done more trials in affective disorders and schizophrenia, while United States respondents had done more studies in neurodegenerative disorders, pain, other CNS, and other non-CNS therapeutic areas.

Regional differences were also noted in the responses to the opinion items. Respondents from outside the United States agreed more strongly than the United States respondents that the inclusion of SIB assessments has improved subject safety (82.9% agreed or strongly agreed outside of the US, 62.1% in US); that the data obtained are the most useful to judge patient risk (54.0% agreed or strongly agreed outside of the US, 41.3% in US); that raters do not feel comfortable asking about SIB (13.6% agreed or strongly agreed outside of the US, 7.4% in US); and that the scales add clinical value (70.8% agreed or strongly agreed outside of the US, 58.7% in US). Yet similar proportions across the two regions agreed or strongly agreed that their site staff feel prepared to handle SIB reports (85.8% for US vs. 81.2% for outside the US) and that training on administering the SIB assessments was helpful (71.1% agreed or strongly agreed outside of the US, 67.0% in US).

United States respondents were more likely to identify the accuracy of lifetime data as a challenge (56.6% vs. 47.0%, respectively), while, as might have been anticipated, translation issues presented a larger problem for respondents outside the United States (33.9% vs. 5.2%) (Table 5). The perceived benefits of prospective assessment were very similar across regions (Table 6).

Analysis by training and region. One particularly interesting difference was also found based on the respondent’s training and location. A greater proportion of respondents trained as neurologists from the United States agreed or strongly agreed that their staff do not feel comfortable asking subjects about SIB compared to psychiatrists from the United States, 13.0 percent versus 4.1 percent, respectively. The same pattern was seen for outside the United States where the corresponding proportion for neurologists was 26.4 percent compared to 9.1 percent of psychiatrists. Likewise, fewer neurologists (65.2%) than psychiatrists (98.6%) in the United States also agreed or strongly agreed that their staff feel prepared to handle reports of SIB. These proportions are very similar outside the United States where 65.3 percent of neurologists and 89.3 percent of psychiatrists feel their staff are prepared to handle SIB reports.

Analysis by role at site and region. The most notable differences in the problems identified by role in the United States were that PIs were less concerned about the ability to get accurate lifetime data (21.4% for US PIs vs 35.2% for US non-PIs) and more concerned about the time it takes to administer the scale (17.5% for US PIs vs 10.5% for US non-PIs). Challenges and perceived benefits outside the United States were similar by role.

Analysis by those responsible for conducting assessments and region. Outside the United States, those responsible for conducting SIB assessments tended to agree or disagree more strongly with the opinion items than those not responsible for conducting assessments. For example, outside the United States, 86.2 percent of respondents responsible for doing SIB assessments agreed or strongly agreed that the site is prepared to handle reports of suicidal ideation and behavior, while 62.2 percent of those not responsible for doing assessments agreed or strongly agreed. However, there was less of a difference between these two groups in the United States: 87.5 percent of respondents who are responsible for doing assessments agreed or strongly agreed, while 79.2 percent of those not responsible for doing assessments did so.

An exception to this is the statement that the benefit of including assessments is worth the additional burden, where differences based on responsibility for SIB assessment were not apparent. The perceived problems and benefits were largely similar for those responsible for doing assessments or not, both within the United States and outside the United States. However, regardless of region, those responsible for conducting the assessments were slightly more likely to report difficulty gathering accurate lifetime data (48.4% vs. 44.6%), and were less likely to identify training as a problem (16.8% vs. 25.9%).

DISCUSSION

This initial systematic survey found that the inclusion of prospective SIB monitoring in clinical trials is generally viewed positively by sites responsible for its implementation. Respondents reported that the inclusion of SIB assessments has improved subject safety by assisting in the identification of patients at risk of SIB and do not report undue burden related to the requirement for prospective SIB assessments. At the same time, they do not see a strong link between the data they collect and the final label that will ultimately guide prescribers in the use of the product. Respondents also do not appear to be completely convinced that the available assessment tools are optimally designed: roughly half of respondents did not feel that the information gleaned is the most relevant for judging a subject’s suicide risk. This may be because they do not feel the assessments completely replace clinical judgment, which incorporates all the information available to the clinician.

Several challenges in the use of SIB assessments in clinical trials were identified in this study, many of which have implications for the quality of the data generated. Although not consistently reported by all sites, it is of concern that approximately a quarter of respondents reported challenges in identifying the correct version of the assessment instrument to use, obtaining appropriate translations, or receiving adequate training. Sponsors can avoid many of these issues by ensuring that sites are provided with the right versions of assessment instruments and the correct translations at the outset of a trial.

The nature and type of training on how to conduct SIB assessments that is provided to sites may also need further attention, though this is tempered somewhat by the finding that those responsible for conducting these assessments did not consistently report this as problematic. Likewise, though only a minority, it is noteworthy that so many sites (roughly 17% in both US and outside the US) report they are uncertain what to do if a subject reports experiencing SIB during a trial.

The difficulty of obtaining accurate lifetime SIB history information at baseline was identified as the major challenge across regions. To the extent that such baseline data may be used to provide context for changes observed during a clinical trial (treatment emergent events), this may present a problem for the field. While our results do not directly address the accuracy of baseline SIB assessments, they do raise the question of how accurate they are, and suggest that this may need further study. In other areas of research, calendaring methods (e.g., timeline follow-back approach,[6] which has been used to assess past alcohol and drug use) have been useful in improving the accuracy of historical information.

Respondents from countries outside the United States, most of whom were trained as psychiatrists, appear to have a slightly more favorable view of the instruments. However, non-United States sites were somewhat less likely to feel comfortable conducting these assessments. This discomfort was more notable when comparing the responses for neurologists to psychiatrists in both the United States and outside the United States. Although both regions had similar level of agreement that the site staff know how to handle SIB reports, there were still notable numbers of sites (about 5%) in both regions that indicated they were not confident staff know what to do. More comprehensive training of the investigational site staff at study initiation may help address this by encompassing not just the administration of the instrument as an adjunct to clinical judgment of suicide risk, but also ensuring that site investigators and staff have an appropriate plan for addressing SIB should it occur and for documenting the actions taken in response. Further, recommendations on how and where to fit SIB assessments into clinic visits may also be helpful.

That sites do not perceive a link between the data they collect and the information on SIB that may appear in the prescribing information ultimately approved is at first glance puzzling. However, it could be due to the lack of experience among site personnel with translating clinical study results into labeling information or their perception that data from one site may not have a large impact within the context of a multisite trial. Moreover, despite the widespread implementation of SIB assessment in clinical trials, the results do not yet routinely show up in the final prescribing information so it may be there are simply too few examples to clearly establish such a link in respondents’ minds. This may change as the number of products with this information would be expected to increase in coming years.

The open-ended questions provided an opportunity for respondents to comment on whatever aspects of SIB assessment were most salient for them. Many comments were positive in nature, particularly regarding the perceived increase in subject safety. Nevertheless, other issues not addressed in the survey also emerged, such as the use of SIB assessments in cognitively impaired populations, particularly in trials involving Alzheimer’s disease subjects. The extension of SIB assessments to these populations bears further scrutiny and development.

Open-text comments from respondents regarding the specific SIB assessment tools currently in use at the sites were mixed, with some respondents reporting that they are working well and others complaining they were too long, confusing, or difficult to use. In order to be inclusive and to not overly burden respondents, we specifically chose not to ask directly about any specific SIB assessment instrument. Though we believe, based on our collective experience, that the C-SSRS is the questionnaire most commonly used, our survey did not allow for a systematic assessment of it or any other SIB assessment instrument.

Limitations of this study include the internet-based survey methodology employed, which relies on self-report with no independent verification of information. There is also uncertain generalizability to the large number of sites conducting SIB assessments for clinical trials, especially given the recruitment of survey sites based solely on CNS trial experience. Responses may also not fully capture the sites’ total experience with SIB assessments. Survey items may have lacked the sensitivity to detect certain issues, such as use of these scales cross-culturally. Finally, no questions were asked about which specific SIB assessment tools were used at the site or how they monitored SIB as standard practice prior to the issuance of the guidance, which would have provided useful context.

In summary, based on the results of this survey, it appears that the inclusion of SIB assessment in trials has the potential to meet the FDA’s chief intent of identifying subjects at risk: the large majority of respondents identified this as the most important benefit. Yet challenges also emerged, some of which have the possibility to negatively impact data quality if not addressed. This study offers an initial look at how SIB assessment is viewed by CNS clinical trial sites following the release of the draft FDA guidance and may help guide stakeholders’ use of these assessments in future trials.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of ISCTM staff members Carlotta McKee, Mary Bea Harding, and Joe Cocchini, Sr. in the conduct of the survey and operational support in preparation of this manuscript.

References

1. United States Food and Drug Administration Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Guidance for Industry. Suicidality: Prospective Assessment of Occurrence in Clinical Trials: Draft. Sept 2010. www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidelines/UCM225130.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2013.

2. Hammad TA, Laughren T, Racoosin J. Suicidality in pediatric patients treated with antidepressant drugs. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(3): 332–339

3. Stone M, Laughren T, Jones ML, et al. Risk of suicidality in clinical trials of antidepressants in adults: analysis of proprietary data submitted to US Food and Drug Administration. BMJ. 2009;339(2):b2880.d

4. United States Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration. FDA Advisory: Suicidality and Antiepileptic Drugs. 2008. http://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/PostmarketDrugSafetyInformationforPatientsandProviders/UCM100190. Accessed June 1, 2013.

5. Posner K, Oquendo MA, Gould M, et al. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1035–1043.

6. Gassmann-Mayer C, Jiang K, McSorley P, et al. Clinical and statistical assessment of suicidal ideation and behavior in pharmaceutical trials. Nature 2011;90:554–560.

7. Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Timeline Follow-back: A technique for assessing self-reported ethanol consumption. In: Allen J, Litten RZ (eds). Measuring Alcohol Consumption: Psychosocial and Biological Methods. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1992:41–72.