by Jennifer Landucci, MD, and Gretchen N. Foley, MD

by Jennifer Landucci, MD, and Gretchen N. Foley, MD

Dr. Landucci is a Fourth-year Psychiatry Resident with Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Dr. Foley is an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry with Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry and Staff Psychiatrist at Wright-Patterson Medical Center, Dayton, Ohio

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2014;11(3–4):29–36

Section Editor: Paulette Marie Gillig, MD PhD, Professor of Psychiatry, Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry, Dayton, Ohio.

Editor’s note: The cases presented herein are fictional and created solely for the purpose of illustrating practice points.

Financial disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Funding: There was no funding for the development and writing of this article.

Key words: Psychotherapy, couples therapy, personality disorder, narcissistic, borderline, histrionic, obsessive-compulsive

Abstract: Personality disordered couples present unique challenges for couples therapy. Novice therapists may feel daunted when taking on such a case, especially given the limited literature available to guide them in this specific area of therapy. Much of what is written on couples therapy is embedded in the larger body of literature on family therapy. While family therapy techniques may apply to couples therapy, this jump requires a level of understanding the novice therapist may not yet have. Additionally, the treatment focus within the body of literature on couples therapy tends to be situation-based (how to treat couples dealing with divorce, an affair, illness), neglecting how to treat couples whose dysfunction is not the product of a crisis, but rather a long-standing pattern escalated to the level of crisis. This is exactly the issue in therapy with personality disordered couples, and it is an important topic, as couples with personality pathology often do present for treatment. This article strives to present practical techniques, modeled in case vignettes, that can be applied directly to couples therapy—specifically therapy with personality disordered couples.

Introduction

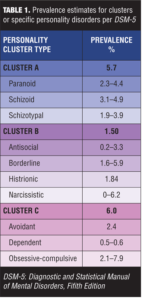

Patients with personality disorders often present a challenge for therapists, especially those in training. Millon opines, “Because personality is the patterning of variables across the entire matrix of the person, efforts to treat the total phenomenon through a single perspective are doomed in advance. When applied to the personality disorders, the truth is not that all forms of therapy are about equally good, but that they are all about equally bad.”[1] Regardless of the type of psychotherapy applied, these individuals present to couples therapy with their own long-standing and pervasive patterns of distorted thought process and maladaptive behavior. The estimated overall prevalence rate is 9.1 percent in the population for any personality disorder.[2] Table 1 lists the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) estimated prevalence for each individually identified personality disorder.

Challenges in the treatment of personality disorders in couples therapy

Personality disorders are often ego-syntonic, meaning the individual in question may not perceive his or her world view as particularly problematic. Forming an effective therapeutic alliance is challenging when the patient does not feel he or she is contributing to the presenting problem(s), and may be complicated by difficulty establishing a trusting relationship with another. Given that many of the pathological intrapsychic processes are thought to develop secondary to family of origin issues or traumatic experiences in childhood, they are especially engrained through years of repetition by the time the adult patient presents for treatment. Addressing the inflexible and rigid nature of maladaptive personality traits requires not only a great deal of skill, but also much patience, on the part of the therapist. If treating a single patient with a personality disorder provokes anxiety or negative counter-transference in the therapist, treating a couple in which both individuals struggle with personality pathology can be quite intimidating indeed. Yet, couples in which there is significant personality pathology on the part of one or both partners are not infrequently encountered in marital therapy.

Personality disorders and marital functioning

The idea that maladaptive personality characteristics may be related to marital dissatisfaction is not new. Multiple studies have examined the relationship between personality style and marital dysfunction or relationship satisfaction. There is evidence that individuals with personality disorders experience greater inter-partner violence in their romantic relationships.[3,4] The level of discord in romantic relationships is higher in young adult individuals with diagnosed personality disorders than those without.[5] Those with Cluster B pathology demonstrated the greatest sustained amount of conflict over a 10-year follow up period from age 17 to age 27; Cluster A or C pathology was related to increased conflict only until age 23 at which point the amount of discord declined to match non-personality disordered controls.[5] Individuals with personality pathology may be more likely to be involved in relationships marked by aggressive behavior on the part of both partners.[6] Borderline and dependent personality features are related to higher levels of verbal aggression and low relationship satisfaction in general. Higher narcissistic personality features in one spouse correlate with lower partner marital satisfaction; higher dependent personality features correlate with higher self marital satisfaction.[6] South et al directly commented on the ego-syntonic nature of personality pathology: “Individuals with pathological personality features have a greater likelihood of being generally unhappy in their marriage, but more important, they may fail to recognize that the source of their unhappiness lies in their own way of processing and interacting with the world.”[6]

Other authors have looked more specifically at borderline personality disorder (BPD), because underlying unstable self-image and affective instability are areas that might elicit partner frustration. While many aspects of the borderline personality structure may decrease or “burn out” with age, affective instability, impulsivity, and anger tend to be the criteria that remain most stable over time.[7]

Women with BPD and men in relationships with women diagnosed with BPD demonstrated less marital satisfaction, higher attachment insecurity, and higher levels of inter-partner violence than controls.[8] Couples in which the female partner had been diagnosed with BPD evidenced more negative behavioral patterns in conflict resolution discussions compared to controls, particularly in regard to dominance behaviors in communication (i.e., controlling and directing the discussions). Women in these couples more frequently engaged in criticism/attack/conflict behaviors (i.e., criticism, blame, threats, non-verbal displays of hostility, negative mind-reading and escalation) than their male partners.[9]

Therapy with personality-disordered couples

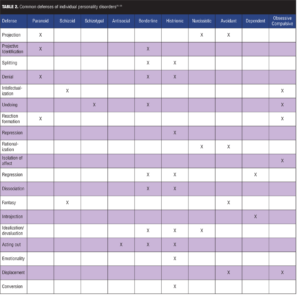

While any combination of personality disorders is possible within a romantic partnership, some combinations appear more often in couples therapy. The underpinnings of certain personality disorders’ mutual attraction suggest a dynamic of complementary strengths and weaknesses rooted in outmoded defenses of their residual “inner children”[10] (see Table 2 for common defenses of various personality disorders). Dicks wrote, “Marital bonds are the nearest equivalent to the original parent-child relationship.”[11] Where more psychologically healthy persons seek a mate base on shared worldview, mutual interests, and goals, individuals with disorders of the self (such as narcissistic or borderline personality disorder) feel inherently incomplete and instead unconsciously seek out a partner to correct or satisfy early self-object failures. Unfortunately, the qualities that first attract two disordered individuals to one another eventually cause discord.[12] Disillusionment results after core self-object needs are repeatedly thwarted by a less than perfect partner.[13] As each partner perceives the other in a more negative manner, defensiveness increases, and cooperation decreases until neither party takes responsibility for the relationship’s problems and instead blames the other.[14] According to Solomon, “Many couples continue to replay old patterns for years, demanding from their partners what was unobtainable from their parents.”[15] Solomon further proposes that successful couples therapy teaches each partner to adequately fulfill each other’s self-object needs.[10,16] As the couple engages in this process over time, each develops progressively healthier and more mature structures of the self. Kohut referred to this evolution of self as “transmuting internalization” and the effect can be profound.[16]

Treating the narcissistic personality disorder (PD) plus borderline personality disorder couple

The narcissistic individual, as described in the text-revised, fourth edition of the DSM (DSM-IV-TR) and more recently the DSM-5, demonstrates “a pervasive pattern of grandiosity, need for admiration, and a lack of empathy.” This person’s personality is theoretically organized around traumatic self-object failures in childhood, and he or she craves, even as an adult, the perfect admiration of a devoted self-object that his or her childhood caregiver repeatedly neglected to provide through “mirroring.”[13] Without having had this essential developmental need fulfilled, the child lingers within the eventual adult despite his or her grown up body, career, and relationships. Romantic partnership may seem like the solution to this developmental dilemma and such an individual may seek out partnership with a borderline individual who, through splitting and idealization, may initially reinforce the perception of grandiosity and perfection in the narcissist.

The borderline individual, as described in the DSM-IV-TR and more recently the DSM-5, demonstrates “a pervasive pattern of instability in relationships, self-image, identity, behavior, and affects often leading to self-harm and impulsivity.”[2,17] This person’s primary defenses reflect a very early developmental stage when infancy needs (e.g., feeding, cleaning, security) were neglected, resulting in attachment failures.[10] This individual sees others as all good or all bad depending on whether the borderline individual’s immediate needs are being met.[18] Romantic attraction reflects an absolute view of the other as all good when conscious needs are being met and all bad when they are not. Naturally, no partner can sustain this idealization. Furthermore, the borderline individual’s tendency to project unacceptable aspects of their own character onto those around them will eventually shatter the perfect image they have of the partner, whom they then devalue and attack.[19] If their partner has a narcissistic personality structure, this devaluation is as traumatic as the self-object failures of childhood and causes intense pain. The narcissistic individual may react with rage or withdrawal, which then triggers the borderline partner’s abandonment fears.

When this couple presents for therapy, the person with narcissistic personality disorder will likely see his or her counterpart as the principle “problem,” thus it may be difficult to engage the narcissistic partner in the work of couples therapy where the system, and not its individual parts, is presented as the target of treatment. Additionally, this person may be alienated if not treated empathically by the therapist, who must simultaneously appreciate his or her counter-transference feelings toward both partners, as well as toward the couple as a unit. The therapist must take care not to choose sides even when one partner resorts to blaming, attacking, or distancing when experiencing a narcissistic injury.[13] The injury itself should be validated and addressed by the therapist as a re-activation of childhood fears and disappointments. In this way, the therapist aides the couple in understanding how their dysfunctional exchanges reflect developmental insults and not necessarily problems inherent in the relationship itself. The therapist’s empathy and ability to contain the narcissistic individual’s rage allows that partner to feel safe in session, and the developmental process is rekindled, with the therapist serving as “mirroring self-object.”[13,20,21] As therapy progresses, the couple begins to understand narcissistic injury as the effect of traumatic de-idealization and narcissist rage as the counter-defense. This understanding makes partner withdrawal less alarming for the borderline individual. The borderline partner, drawing from the therapist’s example, begins to satisfy their own self-object needs, appreciate the narcissistic partner’s good qualities again, and the curative fantasy that sparked the narcissistic individual’s initial attraction to this partnership begins to re-emerge.[20] This is not to be confused with “perfect and constant gratification of all needs,”[13] as the narcissistic individual would then have no reason to mature. Hopefully the narcissistic individual internalizes self-object functions enough to maintain self-esteem, with growing tolerance for the occasional frustration. He or she then requires less and less idealization from the borderline partner.[13]

The therapist serves similar roles for the borderline partner by listening to and validating his or her experience of interpersonal conflict and then reframing it in terms of developmental issues.[18] The borderline patient’s tendency to act out is interpreted to that individual as an inability to self-soothe. The therapist models a non-anxious stance for this partner and encourages self-interventions, such as breathing and mindfulness, to dampen the anxious emotional intensity directed at the narcissistic partner, because the partner experiences this intensity as demanding and automatically resists or withdraws from it.[15,18] Individuals with borderline personality disorder also often have difficulty with reality testing and can easily distort even innocuous messages and situations, and so the narcissistic partner’s tendency to withdraw is viewed by the borderline partner as complete abandonment. The therapist helps the borderline partner to more accurately decode his or her partner’s behavior and to send more articulate, less emotionally charged messages to the partner.[15] Applying self-soothing techniques and improved communication skills to ingrained couple conflicts weakens the old patterns of attack-injury-counterattack and allows for an evolution toward healthier conflict resolution.

Case vignette #1

Laura and David had been married for five years when they presented for couples therapy. Laura, who had been in individual therapy for the past two years, had been encouraging David to enter either individual or couples therapy for months. While he had finally agreed to attend, he made it clear from the outset that this was a waste of his time. He introduced himself as an important lawyer who expected the session to end 10 minutes early so he could attend a business lunch with several city officials. He sat angled slightly away from his wife, arms and legs crossed. His phone buzzed part way through the session and he took his time texting a lengthy response. Laura sat rigidly, making furtive glances at David while she answered the therapist’s questions. She had come from a troubled home, graduated high school a year early, and earned her business associate’s degree while working two jobs. She met David while working as an administrative assistant in his law firm. Three years ago she left the firm for a small but growing business, working her way into a senior position. Meanwhile she felt more and more isolated in her marriage. She wanted to start a family, but David had refused to be intimate with her for months. When she quietly shared this, eyes on the floor, hands meekly folded in her lap, David exclaimed, “Don’t try to blame this on me. You’re the one with the problem.” Finally addressing the therapist, David explained how he had recently found Laura in the bathroom in the middle of the night—“She didn’t even notice me, she just kept staring at her hands.” David turned cold eyes on Laura who was holding back tears. “She was holding my razor,” he hissed.

PRACTICE POINT: Developing a therapeutic alliance

The therapist in this situation may experience strong counter-transference toward one or both partners, perhaps a desire to protect Laura from an uncaring and critical David. Registering these feelings in the room could alienate David, who likely would not return for a second session. At this point, the therapist should focus on nurturing a therapeutic alliance with both partners, while remembering that the relationship, and not a particular partner, is the target of treatment. When possible, the therapist should address both sides of the conflict in the same breath to avoid appearing to side with either partner.[15] In this case, the therapist might validate David’s side—“How upsetting to find your wife like that,”—then appeal to Laura to share her emotional state—“What were you feeling, Laura?”

Case vignette #1 continued

Laura explained she had cut herself in early adolescence to escape painful feelings. She quickly added she had never done it with suicidal intent and that she had not planned to cut herself at all that night in the bathroom; it had been enough hold the razor and remember how it used to feel. “Do you know how crazy that sounds?” David interjected. Laura quietly added she felt alone, that David had pulled away physically and emotionally. David vehemently countered, “You left me first!”

PRACTICE POINT: Modeling communication, asking for clarification

Again, the therapist, careful to be empathic to both partners, might ask in a non-judgmental way—“Laura can you help David and me understand what was so painful to you that night, that it was a relief to think about cutting?” David’s overtly hostile response hints at a narcissistic injury. The therapist may be tempted to pursue this immediately but should not forget that Laura just shared vulnerable feelings as well. The therapist might address both sides as follows—“Laura, you feel alone when David withdraws physically and emotionally.David, am I understanding right, that you feel left also?” Asking for clarification here serves two purposes: it models communication that seeks to be accurate and it is a non-threatening way of eliciting the trigger for David’s narcissistic injury.

Case vignette #1 concluded

For the first time during the session, David’s tone took on a vulnerable quality. He explained that Laura had left his law firm. With empathic coaxing, the therapist eventually learned that David had enjoyed having a pretty and admiring wife on hand at the firm’s front desk. He had taken her along to lunches when networking with colleagues and city officials. When she left the firm and became absorbed in her own career advancement, she no longer lavished admiration on him and was too busy to notice his accomplishments. The therapist helped Laura and David appreciate the needs their behavior only covertly conveyed, framing these needs as residual developmental deficits. The therapist modeled how to better articulate these needs and how to respond to each other’s needs empathically. They remained in treatment for two years, learning to conceptualize their conflicts in this way. As Laura and David made progress acting as responsive self-objects for the other, they began to find their relationship mutually satisfy and fulfilling. Toward the end of treatment, they were expecting their first child.

Treating the histrionic PD plus obsessive-compulsive PD couple

The histrionic individual, as described in the DSM-IV-TR and more recently the DSM-5, displays a “pervasive pattern of excessive emotionality and attention seeking.” This person has learned to get his or her needs met by manipulating others through seductiveness, provocation, and exaggerated displays of emotionality. His or her self-perception is one of needing to be the center of attention in order to have value. Similar to the dependent patient, the histrionic individual experiences the self as helpless and feels unable to care adequately for oneself, thus this individual searches for an attentive and ideal caretaker to assist in navigating the normal stresses of life.[22] There is considerable fear of being confronted or abandoned at any moment. Since the histrionic individual is easily influenced by others and tend to experience rapidly shifting and exaggerated-appearing but shallow emotions, it follows that he or she prefers a mate who is more calm and objective, thinks rationally and logically, and is able to help him or her deal with life.[23] The somewhat detached, steadfast, and perfectionistic obsessive-compulsive mate may seem a perfect fit, initially.

The obsessive-compulsive individual, as described in the DSM-IV-TR and more recently the DSM-5, demonstrates a “pervasive pattern of preoccupation with orderliness, perfectionism, and mental and interpersonal control, at the expense of flexibility, openness, and efficiency.”[2,17] This individual generally feels inherently flawed, unlovable, and that life is unpredictable and dangerous without order. He or she believes it is paramount to be “in control” and always in the right to make up for his or her deficits. Further, he or she takes responsibility for others and anything in life that goes wrong.[24] As a result, the obsessive-compulsive person desperately fears being a failure and works overtime to achieve perfectionism. The vivaciousness and spontaneity of the histrionic person offers tempting freedom from his or her mundane routines. Further, the histrionic person’s need for a caretaker leaves the obsessive-compulsive individual feeling like a competent guardian, allowing him or her to feel strong and fully capable, perhaps for the first time.[23]

When this couple presents for therapy, both parties are firmly (though perhaps unconsciously) entrenched in their pathological and maladaptive ways of relating and behaving. Unfortunately for the histrionic individual, the usual provocations are no longer eliciting the expected response from his or her partner, leading to escalating behaviors (somaticism, affairs, other impulsive acts) that further compound a residual feeling of being “not good enough.” This feeling in turn exacerbates the histrionic individual’s fear of abandonment, resulting in even more dramatic attempts to capture attention. Over time as the behaviors and provocations grow tiresome to the partner, the obsessive-compulsive partner starts to feel exploited. Since the obsessive-compulsive partner has difficulty expressing emotions, especially those that are negative, he or she will express anger in passive-aggressive ways (withdrawing, becoming more of a “workaholic”) which only serve to further inflame his or her histrionic partner’s insecurity. The resultant more extreme emotional displays or acting-out behaviors of the incensed histrionic partner escalates the problem and the entire cycle repeats.

One observer saw these couples as polarized halves that together form a full personality in the marital relationship.[25] Another described each partner as having qualities the other craves, but once either is threatened, defensiveness increases and those qualities lose their luster.[14] In general, as each partner becomes more defensive, that partner externalizes responsibility for the relationship problems and opts instead to blame the other. This defensiveness further coerces the other into behaving in maladaptive, repetitive ways that mirror previous parent-child relationships. Both parties settle into regressive positions painting the other as defective, while secretly believing they themselves are flawed.

Early resistance in couples therapy is often related to the fantasy both partners harbor that the therapist will “fix” the other. Instead, the therapist must assist each partner to understand and accept responsibility for their part in the dysfunction as a whole without assigning blame to either party. Once the fantasy of “fixing” the other is dispelled, the therapist can then help the couple escape their problematic push-pull dynamic by assisting the couple in setting collaborative goals.

Case vignette #2

Alice and Eugene arrived separately for their initial appointment. While Eugene was 15 minutes early, Alice arrived 10 minutes into the hour. Alice cheerfully explained, “I was getting my nails done, see—I just love this orange! I became instant friends with the lady next to me. We just couldn’t say ‘good bye.’ I’m meeting her for lunch next week.” The therapist noticed Eugene appeared indifferent to his wife’s giddy outpouring and her provocative style of dress. Eugene, in fact, said very little at first. Alice’s explanation of their presenting problem was emphatic but vague–“I’m just so unhappy and he doesn’t even care! I could be bawling my head off over the phone, and he’ll say he’s gotta go, he’s working on some hideous project! Don’t you love me anymore, Genie?” The therapist gathered from Eugene that he was quite enamored with Alice in the beginning, that her energy and flirtatious manner had made him feel alive and desired. He had enjoyed taking care of things like balancing her checkbook for her, both because she seemed so desperately to need taking care of, and because she lavished praise and gratitude on him– “I guess it made me feel like a real man.” After a while, Eugene began to feel frustrated with Alice’s flagrant disregard for his well-meaning guidance. “If I was going out of town, I would write everything out for her, like what bills to expect, which account to pay them from. Things like that. Then I would get home and find the mailbox overflowing because she had never even checked it.” Alice rolled her eyes at this, vehemently exclaiming, “You don’t care what I do! I could set the house on fire and you wouldn’t bat an eye.” Eugene admitted his earlier tolerance had turned more into resigned avoidance–“Everything about Alice is haphazard, I can’t keep up. At least at work I have control. I can make things right there.”

PRACTICE POINT: Providing reassurance and understanding

Each half of the histrionic/ obsessive-compulsive couple has a drastically different personality structure (dramatic vs. controlled) and communication style (vague vs. detailed and rational). After the magnetism of this contrast fades, each partner may feel alien in the relationship. They may verbalize that the other acts crazy, but harbor the secret insecurity that they themselves are really the crazy one. The therapist is wise to address this underlying fear so that the couple can direct their energy toward treatment. The therapist might do so by normalizing their feelings, “You are probably familiar with the expression ‘opposites attract.’ Those same differences that draw people together can make them feel crazy later on. Is this something that either of you feel at times?”

Case vignette #2 continued

Alice nodded, eyes wide. “I love Genie so much but he’s like one of those aliens on TV that’s all logical,” she said, throwing her hands in the air. “I do all this stuff that even I know is obnoxious, just to get him to respond. And he just… keeps going.” Alice sighed heavily, adding, “Like that pink bunny, only less fun.” Eugene was looking at his wife now, “What does that mean?” He sounded genuinely curious. “I see you. I see the messes you make. How can I not? I’m the one who picks up the pieces.” Alice countered with, “Sure you pick up the pieces, then you run off to work. I just feel so crazy because you don’t even get mad. Doesn’t anything I do matter to you?” Now Eugene looked exasperated, “Yes, you sabotaging our life matters to me.” Alice’s face flushed and she exclaimed, “What life?!”

PRACTICE POINT: Setting common goals

Here the therapist observes a little of the dysfunction going on in this couple’s home. Their differences are driving them apart. The therapist, however, can also see what they have in common: they are both invested in the relationship. Otherwise, Alice would not try so hard to get Eugene’s attention and Eugene would not still be cleaning up after her. Sharing this interpretation with the couple may help them reframe their antagonistic dynamic as a partnership with shared goals. With this couple the therapist might say, “Let’s take a moment to understand what’s going on. You two are locked in this cycle where neither of you is happy, am I right?” They nodded their agreement. “And you’re both sticking it out even though either one of you could decide to leave?” Again they nodded, although more tentatively. “It sounds like both of you are really invested in this relationship. You just need help figuring out how to make it work.” This last statement offers hope in what has likely felt like a hopeless situation.

Case vignette #2 concluded

As therapy progressed, Eugene and Alice began to engage with each other more collaboratively. Alice wanted a more spontaneous and feeling partner. Rather than try to invoke these qualities in Eugene through provocative behaviors, she learned a more constructive approach. By taking him to parties and events she enjoyed and coaching him on how to engage with her, she again felt desired in the relationship. Eugene had a reciprocal role in teaching Alice some basic organizational skills. Further, he became more able to tolerate and articulate his feelings when Alice behaved in a dramatic fashion, which prevented the usual dynamic of withdrawal followed by escalation. Each was given the responsibility to help the other accommodate his or her own needs, and each was willing to be coached by the other as they appreciated this was important for the health of a relationship they both clearly valued.

Conclusion

Personality disordered patients perceive and interact with others using the template they developed during an often painful childhood. The patterns of thought and behavior that may have been adaptive for survival during the psychological crises of their childhoods do not serve their adult relationships well and can generate substantial distress and conflict in their romantic partnerships. It is not uncommon for personality disordered individuals to attract each other due to complementary strengths and deficiencies. The therapist that treats such a couple faces not just the challenges of each partner’s personality pathology, but the interactional system their partnership comprises. Therapists still in training may find this situation especially daunting. An understanding of the underlying psychodynamics of each partner and how they interact with one another is essential. The above practice points provide an orientation for moving forward in couples work especially with certain dyads. One must first establish a therapeutic alliance with both partners (which requires careful attention to transference and counter-transference alike). The therapist can then model more effective communication so each partner is better able to understand the other’s point of view and behavioral patterns.

Reassurance and understanding from the therapist lays the groundwork for a more empathic relationship between partners. Setting common goals helps the couple work on something collaboratively, rather than against one another. A therapist with this roadmap will be more equipped to handle some of the common obstacles faced when treating the personality disordered couple.

References

1. Millon T, Millon CM, Meagher S, et al. Personality Disorders in Modern Life: Second Edition. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2004:117–149.

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press Inc., 2013.

3. Gondolf EW, White RJ. Batterer program participants who repeatedly reassault: psychopathic tendencies and other disorders. J Interperson Viol. 2001;16:361–380.

4. Craig RJ. Use of the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory in the psychological assessment of domestic violence: a review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2003;8:235–243.

5. Chen H, Cohen P, Johnson JG, et al. Adolescent personality disorders and conflict with romantic partners during the transition to adulthood. J Pers Disord. 2004;18:507–525.

6. South SC, Turkheimer E, Oltmanns TF. Personality disorder symptoms and marital functioning. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2008;76:769–780.

7. McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Sanislow CA, et al. Two-year prevalence and stability of individual DSM-IV criteria for schizotypal, borderline, avoidant, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorders: toward a hybrid model of Axis II disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:883–889.

8. Bouchard S, Sabourin S, Lussier Y, Villeneuve E. Relationship quality and stability in couples when one partner suffers from borderline personality disorder. J Marital Fam Ther. 2009;35:446–455.

9. De Montigny-Malenfant B, Santerre ME, Bouchard S, et al. Couples’ negative interaction behaviors and borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2013;41:259–271.

2013;41:259–271.

10. Solomon MF. Treating narcissistic and borderline couples. In: The Disordered Couple. Carlson J, Sperry L (eds). Bristol, PA: Brunner/Mazel; 1998:239–257.

11. Dicks HV. Marital Tensions. New York: Basic Books; 1967.

12. Dreikurs R. The Challenge of Marriage. New York, NY: Hawthorn; 1946.

13. Kalogjera IJ, Jacobson GR, Hoffman GK, et al. The narcissistic couple. In: The Disordered Couple. Carlson J, Sperry L (eds). Bristol, PA: Brunner/Mazel; 1998:207–238.

14. Sperry L. The Together Experience: Getting, Growing, and Staying Together in Marriage. San Diego: Beta Books; 1978.

15. Solomon MF. Treatment of the narcissistic and borderline disorders in marital therapy: suggestions toward an enhanced therapeutic approach. Clinical Social Work Journal. 1985;13:141–156.

16. Kohut H. Restoration of the Self. New York: International Universities Press; 1977.

17. American Psychiatric Association. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

18. Oliver M, Perry S, Cade R. Couples therapy with borderline personality disordered individuals. The Family Journal: Counseling and Therapy for Couples and Families. 2008;16:67–72.

19. McCormack CC. Treating Borderline States in Marriage: Dealing with Oppositionalism, Ruthless Aggression, and Severe Resistance. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, Inc.; 2000.

20. Ornstein A. The curative fantasy and psychic recovery: contribution to the theory of psychoanalytic psychotherapy. J Psychother Pract Res.1992;1:22.

21. Kohut H. How Does Analysis Cure? Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press; 1984.

22. Sperry L, Maniacci MP. The histrionic-obsessive couple. The Disordered Couple. Carlson J, Sperry L (eds). Bristol, PA: Brunner/Mazel; 1998:187–205.

23. Bergner R. The marital system of the hysterical individual. Fam Process. 1977;16:85–95

24. Sperry L. Handbook of Diagnosis and Treatment of DSM-IV Personality Disorders. New York, NY: Brunner/Mazel; 1995.

25. Dicks HV. Object relations theory and marital studies. Br J Med Psychol. 1963;36:125–129.

26. Gabbard GO. Psychodynamic Psychiatry in Clinical Practice: Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.; 2005.

27. Kernberg OF. Borderline Conditions and Pathological Narcissism. New York: Aronson; 1975.

28. PDM Task Force. Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual. Silver Spring, MD: Alliance of Psychoanalytic Organizations; 2006.