by Jennifer M. Giddens and David V. Sheehan, MD, MBA

by Jennifer M. Giddens and David V. Sheehan, MD, MBA

J. Giddens is Co-founder of the Tampa Center for Research on Suicidality, Tampa, Florida; and Dr. Sheehan is Distinguished University Health Professor Emeritus, University of South Florida College of Medicine, Tampa, Florida.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2014;11(9–10):172–178

Funding: There was no funding for the development and writing of this article.

Financial Disclosures: J. Giddens is the author and copyright holder of the Suicide Plan Tracking Scale (SPTS) and is a named consultant on the Sheehan-Suicidality Tracking Scale (S-STS), the Sheehan-Suicidality Tracking Scale Clinically Meaningful Change Measure Version (S-STS CMCM), the Pediatric versions of the S-STS, and the Suicidality Modifiers Scale; Dr. D. Sheehan is the author and copyright holder of the S-STS, the S-STS CMCM, the Pediatric versions of the S-STS, the Sheehan Disability Scale (SDS), and the Suicidality Modifiers Scale, is a co-author of the SPTS, and owns stock in Medical Outcomes Systems, which has computerized the S-STS.

Key words: Suicide scale, suicide assessment, suicide risk, suicide attempt, suicide, suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, suicidality, C–SSRS, FDA 2012 Draft Guidance Document

Abstract: Objective: The United States Food and Drug Administration’s newest classification system for suicidality assessment anchors suicidal ideation to various combinations of passive suicidal ideation, active suicidal ideation, method, intent, and plan. This is based upon the suicidal ideation categories in the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale. Although there are 32 possible combinations of these suicidal ideation phenomena, the Food and Drug Administration’s 2012 system and the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale accommodate six combinations. We use a case study to explore the impact of possible type II errors on suicidality classification posed by not including remaining 26 possible categories. Methods: A suicidal subject kept detailed daily records of her experience of suicidality over two separate intervals of eight-months’ and nine-months’ duration. These records permitted classification of individual events into each of the possible 32 suicidal ideation combinations. Results: Although only a small percentage of all events of suicidality from either collection period fell outside of the Food and Drug Administration’s classification system and the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale categories, those that were not so categorized constituted a large percentage of the time this subject experienced suicidality. When these two timeframes were aggregated, more than half of the subject’s time spent experiencing suicidality fell into the suicidal ideation combinations not captured by the Food and Drug Administration’s classification system and the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale categories Conclusion: This case study suggests that type II errors in the Food and Drug Administration’s classification system and in the Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale categories for suicidal ideation may represent important omissions.

Introduction

In 2010, the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued a draft guidance document on the prospective assessment of suicidal ideation and behavior in drug trials.[1] It recommended using the Columbia Classification Algorithm for Suicide Assessment (C-CASA)[2] “as the standard for coding suicidality data.”[1] The C-CASA contains a total of nine categories (4 categories viewed as suicidal, 3 as indeterminate, and 2 as non-suicidal).[2]

This draft guidance was updated in August of 2012[3] by replacing the nine-category C-CASA with a “set of 11 preferred categories” to prospectively capture events of suicidality.[3] These 11 preferred categories (referred to as the FDA-CASA 2012) are divided into five categories of suicidal ideation, five categories of suicidal behavior, and the category self-injurious behavior without suicidal intent.[3]

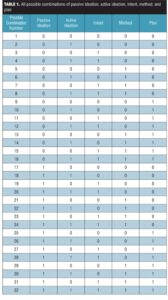

The five recognized categories of ideation are linked to the presence or absence of passive ideation, active ideation, a method, intent, or a plan. These categories, however, do not represent all combinations. As shown in Table 1, there are a total of 32 possible combinations of passive ideation, active ideation, method, intent, and plan (2 response options to the power of 5 domains=32). The FDA-CASA 2012 and Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C–SSRS)[4] categories are both limited to six of these 32 combinations (i.e., the 5 identified combinations plus the null of the 5). The null is the possible combination number 1 in Table 1.

The purpose of the following case report is to investigate the possible impact of the type II errors in omitting 26 combinations of passive ideation, active ideation, method, intent, and plan.

Methods

A 30-year-old female subject who experienced suicidality almost daily for more than 20 years collected detailed daily data on her events of suicidality. Her first psychiatric diagnosis at age 12 was major depressive disorder (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition, Revised [DSM-III-R]).[5] Four years later, her diagnosis changed to bipolar II disorder (DSM, fourth edition, text revision [DMS-IV-TR]).[6] In 2010, her previous diagnoses were replaced by pervasive developmental disorder, not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS)(DSM IV-TR).[6] Her presentation met criteria for Asperger syndrome in the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Edition (ICD-10).[7] She was very organized, had a very high level of attention to detail, and was highly intelligent by IQ. She reported that her symptoms previously interpreted as hypomania were more closely related to stress from and/or difficulties with communication, being distracted by various stimuli, and periods of excessive focus on topics of interest. All of these are common characteristics found in persons with PPD and Asperger syndrome.

The daily documentation included the possible combination number for each event (as illustrated in Table 1), the amount of time spent experiencing the event, and the number of times the event occurred in the prior day (12:00 am through 11:59 pm). Suicidality was defined as any of the suicidal phenomena captured by page 1 of the 11/12/13 version of the Sheehan-Suicidality Tracking Scale (S-STS),[8] with the exception of non-suicidal self-injury.

For the first set of data, she documented her suicidality events for the prior day every morning for a total of 19,854 events of suicidality over a span of 243 consecutive days (8 months) in a spreadsheet. In this data set, 19,853 of the events contained only suicidal ideation, method, intent, and/or plan. In this data set, there were a total of three events that occurred across two distinct days (i.e., they started before midnight one night and finished after midnight the following morning). For the purposes of tracking, each part of an event that spanned across two days was counted as a separate event, with one occurring on the first day and another on the second day.

For the second set of data, she documented her suicidality events in a second spreadsheet over the ensuing 274 consecutive days (9 months) for the prior day every morning for a total of 21,210 events of suicidality. In this data set, 21,186 of the events contained only suicidal ideation, method, intent, and/or plan. In this data set, there were a total of two events that occurred across two distinct days, and each of these events were counted as two distinct events.

The only difference between the data collected during these two timeframes was that, in the first timeframe, events of only passive and/or active suicidal ideation were collected under an aggregate category called suicidal ideation. In contrast, passive and active suicidal ideation categories were disaggregated from one another in the second timeframe.

Passive suicidal ideation was defined as a positive response (>0) to the question “How seriously did you think (even momentarily) that you would be better off dead, need to be dead or wish you were dead?”8 (question 2 on the S-STS) while active suicidal ideation was defined as a positive response to the question “How seriously did you think (even momentarily) about harming or hurting or injuring yourself—with at least some intent or awareness that you might die as a result—or think about suicide (killing yourself)?”[8] (question 3 on the S-STS). In the first timeframe, any positive response to either of these in isolation or in combination was subsumed within the category of suicidal ideation.

Results

Set 1. Table 2 shows the details of the first set of data collection based upon the combination experienced. For example, possible combination number 13 (only method and plan) was experienced 15 times on five distinct days and amounted to over 140 minutes during the entire eight months. This combination constituted 0.07 percent of the total number of events and 0.57 percent of the number of minutes spent experiencing suicidality and occurred on 2.05 percent of the days. We are unable to retrieve possible combination numbers 2, 17, and 18, since passive and/or active suicidal ideation were aggregated rather than disaggregated in this earlier dataset.

The last two columns to the right in Table 2 identify which combinations would be missed by the FDA-CASA 2012 and C–SSRS suicidal ideation category definitions. (For simplicity, the navigation instructions for the Suicidal Ideation section of the C–SSRS have been ignored here.) As the bottom row of this table indicates, 26 of the 32 possible combinations of suicidal ideation are not recognized by the FDA-CASA 2012 and C–SSRS definitions.

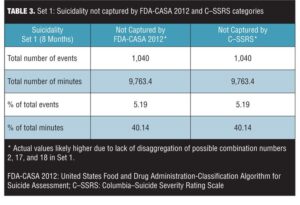

Table 3 shows the total number of events, total number of minutes, percentage of events, and percentage of minutes not recognized by the FDA-CASA 2012 and C–SSRS category definitions that were observed during the first eight-month period of observation by the subject of this report. Although only 5.19 percent of the events that occurred would not be recognized, 40.14 percent of the total minutes this subject experienced suicidality in this eight-month period would not be recognized by the FDA-CASA 2012 and the C–SSRS categories. The total amount of time spent in unrecognized events equaled 9,763.4 (9,763) minutes (162 hours, 43 minutes, and 24 seconds) of suicidality over this eight-month period.

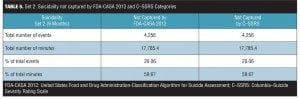

Set 2. Data from Set 2 are shown in Table 4. One possible combination not recognized by the current classification system, possible combination number 18 (only passive and active suicidal ideation), occurred 3,327 times on 274 distinct days and consumed 3,750.6 minutes during the entire nine months. This combination constituted 15.69 percent of the total number of events, 12.58 percent of the number of minutes spent experiencing suicidality, and occurred on 100 percent of the days. Table 5 shows the total number of events, total number of minutes, percentage of events, and percentage of minutes not recognized by the FDA-CASA 2012 and C–SSRS category definitions. Although only 20.06 percent of the events that occurred could not be classified, they represented 59.67 percent of the total minutes (or 17,785.4 minutes) this subject experienced suicidality in this nine-month period.

Discussion

The data from these two data sets suggest that the combinations missed by the FDA-CASA 2012 and the C–SSRS categories do occur in real world experience. Although they constitute a minority of all events experienced, they consumed a large amount of time spent in suicidality by this subject.

Dataset 1 collected “passive and/or active suicidal ideation without method, intent or plan” as one category. Dataset 2 disaggregated this category into combinations 2, 17, and 18. As a result, what are three event combinations in the second dataset are counted as only one category in the first dataset. Combination 18 occurred frequently during the timeframe of the first dataset and cannot be captured as a unique combination by the current FDA-CASA 2012 classification system. When we combined combinations 2, 17, and 18 in the second data set and compared it to this aggregate category in the first data set, the number of events of suicidality, the time spent, and the distribution percentage of suicidality event combinations 2, 17, and 18 in both datasets were very similar. When we compared the two datasets they appeared very similar in most respects.

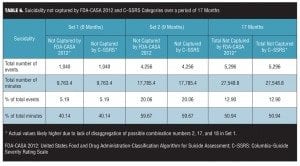

In aggregate, across the combined 17-month period of observation, only 12.9 percent of the events that occurred cannot be classified by the FDA-CASA 2012 and C–SSRS categories. However, these represented 50.94 percent of the total minutes this subject experienced suicidality in this 17-month period (Table 6).

The number of events, the number of minutes, the percentage of events, and the percentage of minutes not captured by the FDA-CASA 2012 and the C–SSRS categories over this 17-month timeframe would likely be higher if the first data set had disaggregated possible combinations 2, 17, and 18.

Limitations. The use of only one subject for this case study means these findings may not be generalizable to other cases of suicidality. The study has all the limitations inherent in the interpretation of single case studies. It will need to be replicated in larger, more diverse samples before having confidence in the findings.

Conclusion

The data suggest that the categories recommended in the FDA-CASA 2012 and in the C–SSRS are incomplete in capturing all combinations of passive and active suicidal ideation, method, intent, and plan that occur clinically (26 of 32 are missed/not recognized). Failure to capture all suicidal ideation combinations that constitute over one half of the patient’s time spent in suicidality has important public health implications.

References

1. United States Food and Drug Administration, United States Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry: Suicidality: Prospective Assessment of Occurrence in Clinical Trials, Draft Guidance. September 2010. https://www.federalregister.gov/articles/2010/09/09/2010-22404/draft-guidance-for-industry-on-suicidality-prospective-assessment-of-occurrence-in-clinical-trials. Accessed October 1, 2014.

2. Posner K., Oquendo M., Gould M et al. Columbia Classification Algorithm of Suicide Assessment (C-CASA): classification of suicidal events in the FDA’s pediatric suicidal risk analysis of antidepressants. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(7):1035–1043.

3. United States Food and Drug Administration, United States Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry: Suicidality: Prospective Assessment of Occurrence in Clinical Trials, Draft Guidance. August 2012. Revision 1. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/Guidances/UCM225130.pdf. Accessed October 1, 2014.

4. Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry 2011;168:1266–1277.

5. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third edition, Revised. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press Inc.; 1987.

6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

7. World Health Organization. ICD-10 Classifications of Mental and Behavioural Disorder: Clinical Descriptions and Diagnostic Guidelines. Geneva. World Health Organization; 2010.

8. Sheehan DV, Giddens JM, Sheehan IS. Status update on the Sheehan Suicidality Tracking Scale (S-STS). Innov Clin Neurosci. 2014;11(9–10):93–140.