by Terry Correll, DO; Julie Gentile, MD; and Andrew Correll, MD Candidate

Dr. Gentile is Professor and Chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. Dr. T. Correll is Clinical Professor of the Department of Psychiatry at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. Mr. A. Correll is with Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine in Dayton, Ohio.

Funding: No funding was provided for this study.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2023;20(7–9):18–26.

Department Editor

Julie P. Gentile, MD, is Professor and Chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio.

Editor’s Note

The patient cases presented in Psychotherapy Rounds are composite cases written to illustrate certain diagnostic characteristics and to instruct on treatment techniques. The composite cases are not real patients in treatment. Any resemblance to a real patient is purely coincidental.

Abstract

Lifestyle medicine is a new paradigm that shifts much of the responsibility toward the patient. There is increasing evidence that healthy lifestyle interventions can be effective treatment adjuncts for some of the most common mental illnesses. This article gives examples of how to integrate evidence-based, healthy lifestyle interventions into the overall treatment of common psychiatric conditions, including anxiety and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Keywords: Healthy lifestyle interventions, lifestyle medicine, nutrition, exercise, motivational enhancement therapy, mindfulness

It is customary to prescribe first-, second-, and third-line treatments in medicine, typically pharmacologic agents, based on the best available evidence. Lifestyle medicine is a new paradigm that shifts much of the responsibility to the patient. In psychiatry, meta-analyses suggest that exercise, low-inflammation and relatively whole-food diets, smoking cessation, sleep improvement, and other lifestyle interventions provide statistically significant benefits for mental health.1,2 These interventions have little to no adverse effects and can reduce the risk of a variety of chronic nonpsychiatric conditions, such as metabolic syndrome, which is 58 percent more likely among those with a psychiatric illness.3

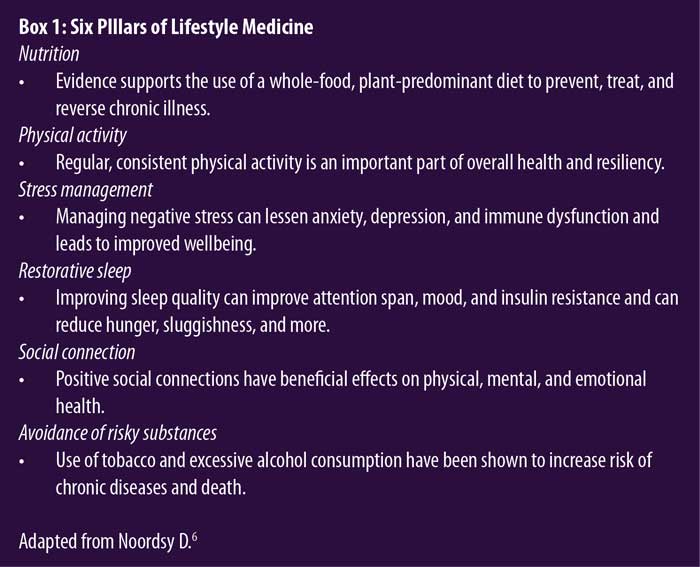

The American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM) defines lifestyle medicine as “the use of evidence-based lifestyle therapeutic approaches, such as a predominately whole food, plant-based diet, physical activity, sleep, stress management, tobacco cessation, and other nondrug modalities, to prevent, treat, and, oftentimes, reverse the lifestyle-related chronic disease that’s all too prevalent.”4 Modern medicine has produced medications, surgeries, and therapies that can be very efficacious in treating acute problems but tend to be less effective at treating chronic disease.5,6 Lifestyle medicine tries to steer away from how medical care can occasionally “devolve…into a muddy compromise” where “partially effective medications” are given to “avoid…talking about the powerful agents of daily life health practices.”6 See Box 1 for a summary of the six pillars of lifestyle medicine.6

Fictional Case Vignette 1

An 18-year-old male college student, A, presented for initial psychiatric evaluation to his college counseling service.

Dialogue 1

A: I think I have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), Doc. Compared to everyone in my study groups, I am the most scatterbrained.

Psychiatrist: How long has this been going on?

A: Since the beginning of my first semester of college, about eight months ago. Though, when I really think about it, it was present throughout my high school days as well.

Psychiatrist: What kind of things are you doing when you are scatterbrained, and how do you feel during those times?

A: I’m usually doing my statistics homework. I can’t seem to work on the same problem for very long, and I just want to jump to something else if I can’t figure it out right away. What was your second question?

Psychiatrist: How do you feel when you are doing your homework?

A: I feel all over the place. I get uptight when I am thinking about the various things that could go wrong in between now and graduation. I know that I’m not as effective when I’m like this, and, when I can’t sleep at night, I feel more tired, which makes it harder for me to concentrate. I would say everything takes me twice as long when I am feeling at my worst compared to when I am 100-percent focused.

Psychiatrist: That sounds difficult, and it seems like it would be hard to attend to your studies this way. Please say more about that.

A: With the harder classes this semester, I’ve been having some more muscle tension in my neck and shoulders, with occasional headaches when I study, which encourages me to procrastinate on assignments. I guess I would say that I feel stressed lately.

Psychiatrist: Does anything help you get into that 100-percent effective mode when you feel focused?

A: I find that drinking two or three of those flavored seltzers that have alcohol in them helpful for my stress. I just don’t want my nosy parents finding out about that.

Psychiatrist: How often are you having these flavored seltzers with alcohol?

A: Oh, not that much, probably two or three times a week. I don’t know why, but I just find it helps. Do you think medical marijuana might also help, Doc? All my friends are doing it.

Psychiatrist: Your question about the medical marijuana is very relevant right now since it’s becoming more and more popular. Anxiety is the most common reason that marijuana is used for medical purposes,7 but the evidence is really unclear regarding whether it actually reduces anxiety.8,9 Also, we don’t know the clear effects of marijuana use on developing brains.10 I find it interesting that the alcoholic seltzer helps, but are there other things that you have discovered that lower your stress levels?

Practice Point 1

Patients often present with attentional difficulties as a symptom of generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). In fact, disrupted attention can present with almost any psychiatric disorder. Individuals can live with unidentified ADHD until faced with new challenges in life, such as going to college, graduate school, professional school, or joining the military. It is most helpful to obtain the history of disturbed attention every day of their entire life, and especially to have demonstrable evidence of such before the age of 12 years.11 A’s attention became problematic well after the age of 12 years, leading the psychiatrist to think it was not ADHD.

The psychomotor agitation of GAD can also appear similar to the hyperactivity component of ADHD. Our patient, A, presented with generalized symptoms of anxiety, worry, and apprehensive expectation, with physical contributions, such as fatigue, muscle tension, headaches, and insomnia. Younger adults tend to experience a greater severity of GAD symptoms than older adults.12 Also, the earlier in life one has symptoms of GAD, the more comorbidity and impairment one tends to have.13,14 It is also important to rule out medical conditions that can include anxiety as a presenting symptom, such as thyroid disease or pulmonary disease. Highly-driven, “type A” healthcare professionals might not diagnose GAD as quickly because they use themselves as a reference group and feel as if the patient is no more keyed up than they are. Such personal bias can become a blind spot during patient encounters.15

Because of A’s young age and recent transition to college life, numerous nonpharmacologic interventions could be tried first that might allow him to adapt and mature to his new routines in college. His use of alcohol might calm symptoms of anxiety in the short-term, but in the long-term, it can significantly worsen symptoms of anxiety by becoming a primary coping mechanism in the place of healthier strategies to deal with anxiety.16,17

In children and adolescents with GAD, the anxieties and worries they experience often concern the quality of their performance or competence in school or sporting events, even when their performance is not being evaluated by others. Our patient, A, reported having troubles completing his statistics homework, which is consistent with how worry in GAD can impair one’s ability to do tasks quickly and efficiently.18 The worrying itself not only took energy, but the concentration issues and sleep problems contributed to a negative downward spiral of functioning. Also, A reported having “nosy” parents, and overprotective parenting practices have been associated with GAD19 with a medium effect size (d=0.52–0.58).20

Clinical Pearls

- The differential diagnosis for attentional difficulties is paramount. Did the patient have symptoms of ADHD as a child, or are the difficulties secondary to another psychiatric condition? In our case vignette, GAD was likely the culprit.

- It may be difficult for a clinician to accurately diagnose symptoms or a condition if they themselves identify with such symptoms or the condition, which can cloud their perspective.

- Allowing normal development and the maturation of coping skills/resilience might be all that is needed at times with younger individuals.

- Reducing stimulation in the environment and avoiding distractions have been shown to decrease procrastination,21 which in a work/academic environment can be particularly helpful for those with difficulties focusing.

Fictional Case Vignette 1, Continued

Dialogue 2

Psychiatrist: You mentioned medical marijuana as something you would like to explore as a treatment option. I wonder if you are interested in other alternative treatment options as well?

A: What do you mean by alternative?

Psychiatrist: For example, are you spiritual at all? Many studies suggest that being more spiritual, in general, can help reduce anxiety.22–25 Also, listening to classical and other calming types of music can lower stress hormone levels, such as cortisol, which tend to increase in those with anxiety.26,27 On the flipside, other types of music, such as hard rock, can increase cortisol levels, which are associated with increased stress.28 Does listening to calmer music or incorporating spiritual practices seem like something that you would like to fit into your daily routine?

A: I am interested in Buddhist teachings, so I could see exploring that more. I listen to music every day while I study, so I could replace some of my heavy metal with Beethoven.

Psychiatrist: Wonderful! I will take note of that so we can talk about it and check up on that next time we meet. Along with the Buddhist teachings, may I also suggest meditating daily? There is strong evidence that meditation can be helpful for anxiety,29 similar to the benefits seen with psychiatric medications. There are many applications (apps) that can help introduce you to meditation.

A: Okay, I can give meditation a try as well. I like all the different things I can do on my own time.

Psychiatrist: Just to help my understanding, would you mind summarizing our plan moving forward today?

Practice Point 2

Ample research has demonstrated the effectiveness of meditation on symptoms of anxiety, as reported in a meta-analyses.27 Mindfulness-based interventions as stand-alone treatment for anxiety display small-to-moderate effect sizes (standardized mean difference [SMD]=0.22–0.56),30 as seen with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), according to a recent large meta-analysis (g=0.33).31 A position paper from the American Academy of Family Practitioners acknowledged that there is evidence supporting the use of meditation as a treatment for anxiety disorders, but that the evidence supporting the use of meditation as monotherapy is limited.32 In light of some evidence that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is more effective than mindfulness-based interventions,33,34 it might be wise to prescribe mindfulness in conjunction with accepted first-line treatments for anxiety.

Spirituality was nonjudgmentally and impartially presented to this patient as a potential treatment. One review found that 69 percent of 32 randomized clinical trials on the effects of spiritual interventions showed a reduction in anxiety symptoms, as well as other psychiatric symptoms.22 Social connection, such as that which may be achieved through attending church services, has been shown to be inversely related with measures of anxiety.35 Connection with a perceived higher power through spirituality might help individuals with anxiety become more comfortable with the things that they cannot control in life and might be a reasonable recommendation if that fits into their personal preferences. Prosocial acts of kindness, often associated with spiritual practices, can reinforce that one’s life is valuable, which in turn might reduce anxiety.36,37

In Case Vignette 1, to share understanding and help crystallize commitment, a teach-back method was employed by the psychiatrist to wrap up their time together. Studies show that this may improve patient knowledge and health outcomes.38 When using teach-back methods, it is a good idea for the psychiatrist to put the responsibility on oneself in order to avoid the appearance of quizzing the patient. Using the term “to help my understanding” speaks to the basic human nature of wanting to help someone in need.

Clinical Pearls

- There are many apps that make meditation more accessible, so if one style is not beneficial for a patient, a different app or a YouTube instructional video might suit them better.

- The website authentichappiness.org has a variety of free strength inventories and evidence-based tools, such as a Meaning in Life Questionnaire, Grit Survey, Gratitude Survey, and Work-Life Questionnaire, that patients can access, which they might find beneficial and can be used by the clinician as discussion prompters in psychotherapy.

- There is ample evidence supporting an association between practicing spiritualism and mental and physical health benefits.23–25,39

Fictional Case Vignette 2

A 68-year-old woman, M, presented for initial psychiatric evaluation, reporting that she felt as if her life had been insignificant so far.

Dialogue 3

Psychiatrist: You said something important on your intake form—you wrote that you thought your life felt meaningless so far. Can you tell me more about what you mean by that?

M: I was really referring to how, during the past several months, I have not been able to feel happy looking back on old photos of my kids and family.

Psychiatrist: Please, tell me more.

M: I just seem unable to experience satisfaction when I think about my past in general. I used to feel happy when I thought about raising my family. I am not sure what is going on.

Psychiatrist: I am sorry you are experiencing that. I can imagine that would be very difficult. How long has this been occurring?

M: About two or three months, I would say.

Psychiatrist: Okay, do you feel some happiness at other times, like when you are around your friends?

M: No, not really. My friends and I have grown more distant lately. I haven’t reached out to them as much, I guess, but it’s partly because I don’t feel as close to them as I once did.

Psychiatrist: How do you understand that?

M: Ever since I finished my chemotherapy for ovarian cancer three months ago, I have noticed that everything seems strange and distant. I think it is related to me grappling with how something so terrible as cancer could have happened to me.

Psychiatrist: Wow! That sounds very trying. (pause) How effective has the cancer treatment been? What is your prognosis?

M: Everything worked. They caught it early, and I am in remission, thankfully.

Psychiatrist: (another therapeutic pause) After having had some time to think about the past couple of months, how do you feel about the whole process of treatment and what happened to you?

M: (tearfully) It was the worst experience of my life. I never want to step inside a medical facility again.

Psychiatrist: (allowing brief time for patient to experience her emotions) Can you tell me more about that?

M: All the needles, the hair falling out in the shower, the chills every night—it was horrible. Sometimes, I will be enjoying something on TV, and then, suddenly, an image of a nurse with a needle and an intravenous (IV) bag of poison pops into my head.

Psychiatrist: You are an incredibly strong person for going through that. You mentioned that you never wanted to step into a hospital again?

M: Ever since my treatment ended, I have not driven close to a medical facility. They asked me to do some follow-up scans, but I don’t have the courage, to be honest with you. I know that it’s not good for me, but whenever I get close to a treatment center, I hear these voices telling me to drive away.

Psychiatrist: Hmm. Has anything else out of the ordinary been happening for you the past couple of months?

M: I’m also having a difficult time sleeping and a hard time remembering the three months that I was on chemotherapy. Do you think that could be dementia? Alzheimer’s runs in my family, and I’m really scared about getting that. (Tearfully) I’m also concerned about ADHD because my grandson has that, and I’m having a hard time concentrating.

Practice Point 3

M’s symptoms of dysphoria and auditory hallucinations were reminiscent of severe depression. Taken into full context, however, M was also experiencing flashbacks and avoidance symptoms associated with her cancer treatment, consistent with the diagnostic criteria of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Auditory pseudo-hallucinations are a feature of PTSD that can often be misconstrued as symptoms of other classic psychotic disorders.40 Data on the frequency of hearing voices in PTSD have a wide variance, occurring in 5 to 95 percent of individuals with PTSD.40–42 M expressed concern that her grandson had ADHD and that she might have it as well, and ADHD does have a high heritability rate.43 However, attention concerns are common in PTSD44 and may even predict the severity of PTSD symptoms.45 Inattentiveness may partially stem from alertness to danger and exaggerated responses to perceived cues of traumatic experiences.11 PTSD is more common in women than men, with the prevalence ranging from 8 to 11 percent for women and 4.1 to 5.4 percent for men.46,47 This discrepancy likely stems from significantly increased risk of sexual abuse, assault, and interpersonal violence in women, exposures that carry high risk for developing PTSD.48

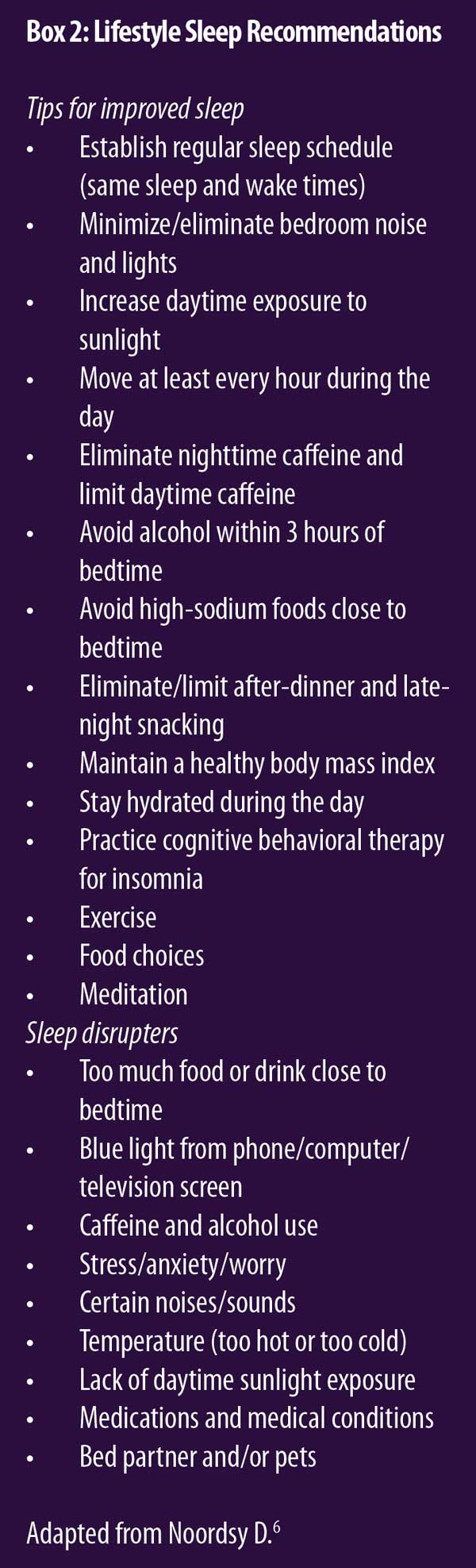

A prominent feature of PTSD is disruption of sleep, commonly from flashbacks or nightmares. One study of in-person CBT for insomnia (CBT-I) as an intervention in patients with PTSD demonstrated improved sleep quality as measured by the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, with effects lasting six months or longer.49 Another study found that CBT-I alone reduced fear of sleep significantly in those with PTSD.50 There are free apps that offer CBT-I, which might be helpful for patients like M. Although CBT-I apps appear efficacious, they might be less effective than in-person sessions.51 However, an app is more accessible and can be easily prescribed as first-line treatment. See Box 2 for a summary of lifestyle sleep health recommendations.6

Clinical Pearls

- M qualified for criterion A of PTSD due to the life-threatening potential of her ovarian cancer, which she experienced as very traumatic.

- PTSD often presents with significant depressive symptoms and can therefore be diagnostically challenging. Starting with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) in 2013, there was the addition of “negative alterations in cognitions and mood” associated with the traumatic event (criterion D) to the diagnosis of PTSD, which includes a persistent inability to experience positive emotions and a persistent negative emotional state.11

Fictional Case Vignette 2, Continued

M continued to experience symptoms of PTSD over the next several months, despite regular follow-up and strong adherence to evidence-based, trauma-focused therapy and medication. Two adequate trials of SSRIs and use of the CBT-I app were only partially effective.

Dialogue 4

Psychiatrist: I’d like to talk to you about adding some healthy lifestyle interventions that can further help with your symptoms. Would that be okay?

M: Sure, if you think it would help.

Psychiatrist: I think exercise could really augment your PTSD treatment. I know we have tried several treatments together, so I’m curious to see if getting your blood moving by doing some physical activities you enjoy could further help. What are your thoughts about that?

M: I don’t know. I’ve never really been a fan of exercise. I’m overweight, and it hurts my knees when I run.

Psychiatrist: Okay. What else makes exercise unattractive to you?

M: I feel lonely exercising by myself, and I don’t like how it makes me sweaty so that I have to change clothes.

Psychiatrist: Yeah, those are downsides. On the contrary, is there anything you enjoy while exercising?

M: I would say I enjoy getting outside and seeing nature. That’s about it (laughs).

Psychiatrist: On a scale of 1 to 10, with 10 being the most ready, how ready are you to make a change to exercise more?

M: Hmm, I would say I am at about a 4.

Psychiatrist: Any reason you are not a 2 or 3?

M: I would really like to get my PTSD symptoms under better control since I’ve been suffering for so long.

Psychiatrist: What would prioritizing exercise look like in your life?

M: Maybe I could walk with a friend. There is a local park near my house that is really pretty.

Psychiatrist: I love your idea of getting a friend involved because that could make it a lot more fun for you. You will also be getting the benefit of bright light therapy from the sunshine and healthy socialization from walking with your friend outside.

Practice Point 4

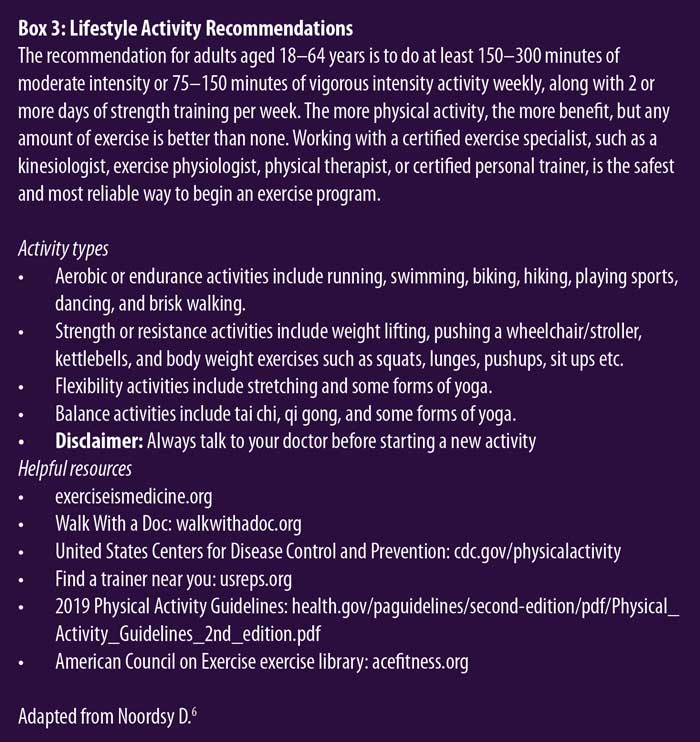

Of course, evidence-based, trauma-focused psychotherapy is the treatment of choice for PTSD.52 However, low-risk healthy behaviors, such as physical activity, may be an effective adjunctive treatment for patients with suboptimal treatment results, as with M. Indeed, a narrative review of the evidence supporting exercise as a treatment in PTSD suggests the hyperarousal symptoms of PTSD can be partially desensitized by adding low-level aerobic activity.53 See Box 3 for the summary of lifestyle activity recommendations.6

M was also concerned about the chance of having dementia because she was unable to recall details surrounding her cancer treatment. This is likely related to criterion D.1 of the DSM-5-TR symptoms of PTSD, which notes that patients are less likely to remember key details surrounding the traumatic event, and criterion E.5, which describes general problems with concentration. Since exercise has been shown to increase hippocampal volume, it may be particularly helpful in patients with PTSD, who have been shown to have decreased hippocampal volume, compared to their healthy counterparts.54 There is also evidence of improved cognitive function and a reduction in PTSD symptomatology in patients who participated in physical activities, but many of these interventional studies investigating the effects of exercise on symptoms of PTSD lack a control group and have small sample sizes.53

Capitalizing on M’s idea of going on walks at the local park with her friend might improve her adherence to exercising more, and the time outdoors might reduce the severity of her PTSD.55 Exercise adherence may be improved through habit formation training that utilizes consistency, rituals, and ways to make the activity more enjoyable.56 Specific, research-backed strategies include developing time-based action plans that incorporate already established routines in life (e.g., “after work I will go to the gym”), listening to music while exercising, or watching television while running on a treadmill.56 Another interesting study trained two groups, one on healthy habit formation and the other on disrupting unhealthy biases, relationships to food, and body image distortions. Both groups displayed initial weight loss, but only the habit-focused group maintained that loss over six months.57 This reinforces how emphasizing the creation of healthy habits and behaviors with M could be quite helpful in the long-term.

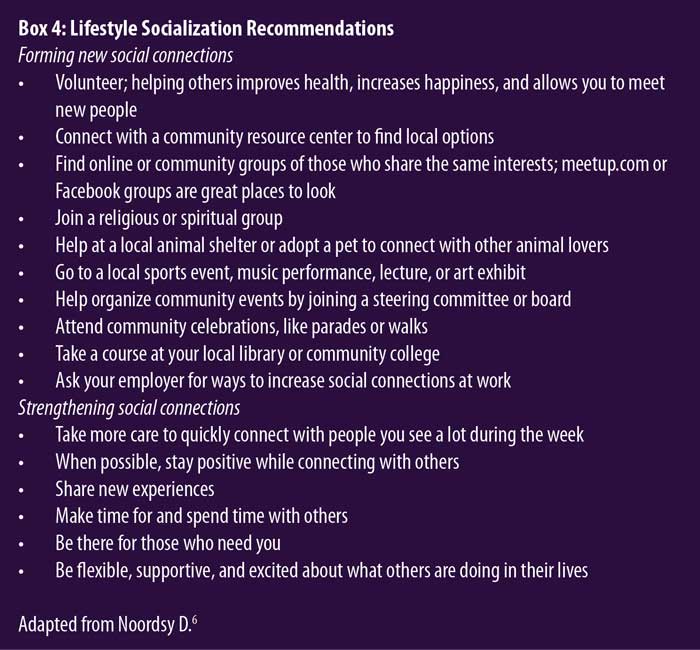

There is good evidence that social support is protective against the development of PTSD with stressful life events,58,59 and it could also help motivate M to continue her walking plan. Promoting healthy social connections is a low-risk resilience-building technique clinicians can utilize in patients with PTSD. Social support has been shown to be particularly effective in improving patient adherence to walking interventions.60 Natural sunlight and bright light therapy have also been shown to be helpful in PTSD treatment.61

Motivational enhancement therapy was utilized during the psychiatrist’s sessions with M. Creating change talk instead of sustain talk and allowing the patient to come up with solutions themselves promoted a greater likelihood of change in M’s willingness to consistently exercise.62 Asking M why she did not give a lower number on a scale of 1 to 10 of motivation helped elicit change talk.63 Guiding focus toward helpful and therapeutic topics is a key skill in psychotherapy.

Clinical Pearls

- Be ready to identify coexisting sleep disorders in patients with PTSD, such as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), which is a very common disorder.11

- Many patients with PTSD utilize alcohol to overcome initial insomnia, which can cause light, broken sleep and worsened sleep quality.64 Alcohol causes sympathetic arousals while sleeping,65 not allowing individuals to fall into deeper stages of high-quality and restorative sleep.

- Be mindful of the increased risk of comorbid social anxiety in patients with PTSD,66 which can further worsen their sense of isolation and dysphoria and hamper full resolution of symptoms.

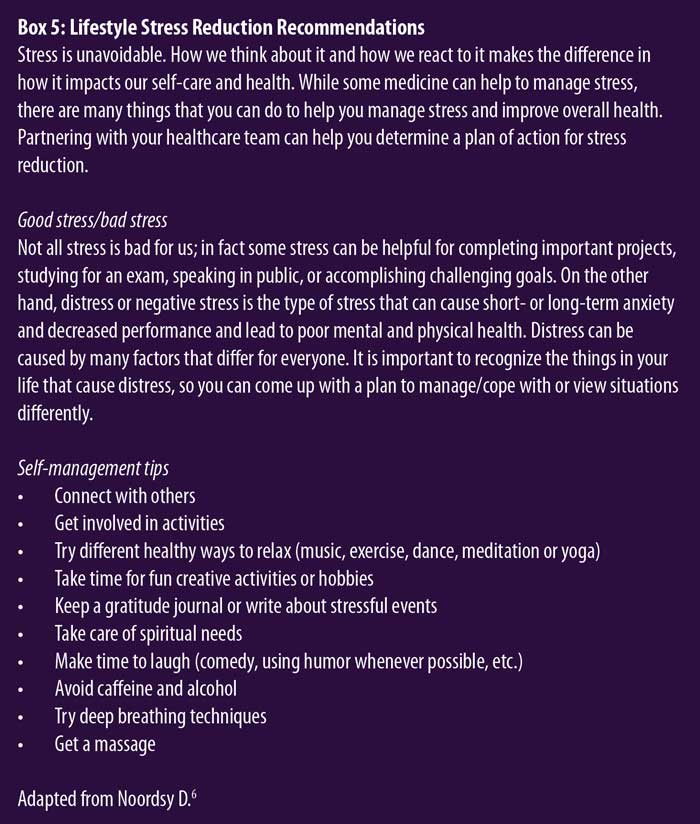

- See Boxes 4 and 5 for recommendations for lifestyle social connection and stress reduction, respectively.6

Conclusion

This article explored the effectiveness of lifestyle interventions as augmentation in psychotherapy for improving symptoms of anxiety and PTSD. When patients are actively involved in the development of their treatment plan, they will typically become more engaged in and adherent to their treatment, and providers can feel empowered by having many digital tools, such as therapeutic apps, to offer their patients that they can use on their own. Additionally, promoting healthy lifestyle interventions to patients can increase their feelings of autonomy, while potentially improving their response to pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions. Finally, encouraging patients to research treatment options and explore ideas on how to better manage their condition will help empower them to choose and hopefully commit to an ongoing healthy lifestyle. Further research exploring the nuances and the efficacy of lifestyle interventions is needed.

References

- van Dammen L, Wekker V, de Rooij SR, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of lifestyle interventions in women of reproductive age with overweight or obesity: the effects on symptoms of depression and anxiety: lifestyle interventions and symptoms of depression and anxiety. Obes Rev. 2018;19(12):1679–1687.

- Firth J, Solmi M, Wootton RE, et al. A meta-review of “lifestyle psychiatry”: the role of exercise, smoking, diet and sleep in the prevention and treatment of mental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):360–380.

- Vancampfort D, Stubbs B, Mitchell AJ, et al. Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(3):339–347.

- Guthrie GE. What is lifestyle medicine? Am J Lifestyle Med. 2018;12(5):363–364.

- Bortz II WM. The disuse syndrome. West J Med. 1984;141(5):691–694.

- Noordsy D, ed. Lifestyle Psychiatry. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2019.

- Azcarate PM, Zhang AJ, Keyhani S, et al. Medical reasons for marijuana use, forms of use, and patient perception of physician attitudes among the US population. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(7):1979–1986.

- Black N, Stockings E, Campbell G, et al. Cannabinoids for the treatment of mental disorders and symptoms of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(12):995–1010.

- Bahji A, Meyyappan AC, Hawken ER. Efficacy and acceptability of cannabinoids for anxiety disorders in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res. 2020;129:257–264.

- Cancilliere MK, Yusufov M, Weyandt L. Effects of co-occurring marijuana use and anxiety on brain structure and functioning: a systematic review of adolescent studies. J Adolesc. 2018;65:177–188.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition, text rev. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2022.

- Wolitzky-Taylor KB, Castriotta N, Lenze EJ, et al. Anxiety disorders in older adults: a comprehensive review. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(2):190–211.

- Campbell LA, Brown TA, Grisham JR. The relevance of age of onset to the psychopathology of generalized anxiety disorder. Behav Ther. 2003;34(1):31–48.

- Le Roux H, Gatz M, Wetherell JL. Age at onset of generalized anxiety disorder in older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005;13(1):23–30.

- Walfish S, McAlister B, O’Donnell P, Lambert MJ. An investigation of self-assessment bias in mental health providers. Psychol Rep. 2012;110(2):639–644.

- Kushner MG, Abrams K, Borchardt C. The relationship between anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorders: a review of major perspectives and findings. Clin Psychol Rev. 2000;20(2):149–171.

- Caldwell TM, Rodgers B, Jorm AF, et al. Patterns of association between alcohol consumption and symptoms of depression and anxiety in young adults. Addiction. 2002;97(5):583–594.

- Plaisier I, Beekman ATF, de Graaf R, et al. Work functioning in persons with depressive and anxiety disorders: the role of specific psychopathological characteristics. J Affect Disord. 2010;125(1–3):198–206.

- Beesdo K, Pine DS, Lieb R, Wittchen HU. Incidence and risk patterns of anxiety and depressive disorders and categorization of generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(1):47.

- Aktar E, Nikolić M, Bögels SM. Environmental transmission of generalized anxiety disorder from parents to children: worries, experiential avoidance, and intolerance of uncertainty. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2017;19(2):137–147.

- van Eerde W, Klingsieck KB. Overcoming procrastination? A meta-analysis of intervention studies. Educ Res Rev. 2018;25:73–85.

- Koenig HG. Religion, spirituality, and health: the research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry. 2012;2012:278730.

- Salsman JM, Pustejovsky JE, Jim HSL, et al. A meta-analytic approach to examining the correlation between religion/spirituality and mental health in cancer. Cancer. 2015;121(21):3769–3778.

- Sherman AC, Merluzzi TV, Pustejovsky JE, et al. A meta-analytic review of religious or spiritual involvement and social health among cancer patients. Cancer. 2015;121(21):3779–3788.

- Cotton S, Zebracki K, Rosenthal SL, et al. Religion/spirituality and adolescent health outcomes: a review. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38(4):472–480.

- Wilson MS, Metink-Kane MM. Elevated cortisol in older adults with generalized anxiety disorder is reduced by treatment: a placebo-controlled evaluation of escitalopram. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19(5):482–490.

- Fischer R, Bortolini T, Karl JA, et al. Rapid review and meta-meta-analysis of self-guided interventions to address anxiety, depression, and stress during COVID-19 social distancing. Front Psychol. 2020;11:563876.

- Labbé E, Schmidt N, Babin J, Pharr M. Coping with stress: the effectiveness of different types of music. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback. 2007;32(3–4):163–168.

- González-Valero G, Zurita-Ortega F, Ubago-Jiménez JL, Puertas-Molero P. Use of meditation and cognitive behavioral therapies for the treatment of stress, depression and anxiety in students. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(22):4394.

- Blanck P, Perleth S, Heidenreich T, et al. Effects of mindfulness exercises as stand-alone intervention on symptoms of anxiety and depression: systematic review and meta-analysis. Behav Res Ther. 2018;102:25–35.

- Gomez AF, Barthel AL, Hofmann SG. Comparing the efficacy of benzodiazepines and serotonergic anti-depressants for adults with generalized anxiety disorder: a meta-analytic review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2018;19(8):883–894.

- Saeed SA, Cunningham K, Bloch RM. Depression and anxiety disorders: benefits of exercise, yoga, and meditation. Am Fam Physician. 2019;99(10):620–627.

- Newby JM, Mewton L, Williams AD, Andrews G. Effectiveness of transdiagnostic internet cognitive behavioural treatment for mixed anxiety and depression in primary care. J Affect Disord. 2014;165:45–52.

- Apolinário-Hagen J, Drüge M, Fritsche L. Cognitive behavioral therapy, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy and acceptance commitment therapy for anxiety disorders: integrating traditional with digital treatment approaches. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1191:291–329.

- Hu T, Xiao J, Peng J, et al. Relationship between resilience, social support as well as anxiety/depression of lung cancer patients: a cross-sectional observation study. J Cancer Res Ther. 2018;14(1):72.

- Shillington KJ, Johnson AM, Mantler T, et al. Kindness as an intervention for student social interaction anxiety, resilience, affect, and mood: the KISS of Kindness Study II. J Happiness Stud. 2021;22(8):3631–3661.

- Miles A, Andiappan M, Upenieks L, Orfanidis C. Using prosocial behavior to safeguard mental health and foster emotional well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic: a registered report of a randomized trial. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(1):e0245865.

- Talevski J, Wong Shee A, Rasmussen B, et al. Teach-back: a systematic review of implementation and impacts. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(4):e0231350.

- Lucchetti G, Góes LG, Amaral SG, et al. Spirituality, religiosity and the mental health consequences of social isolation during Covid-19 pandemic. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2021;67(6):672–679.

- Brewin CR, Patel T. Auditory Pseudohallucinations in United Kingdom war veterans and civilians with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(4):419–425.

- Boon SDN. Multiple personality disorder in the Netherlands: a clinical investigation of 71 patients. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(3):489–494.

- Shinn AK, Wolff JD, Hwang M, et al. Assessing voice hearing in trauma spectrum disorders: a comparison of two measures and a review of the literature. Front Psychiatry. 2020;10:1011.

- Faraone SV, Larsson H. Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2019;24(4):562–575.

- Adams Z, Adams T, Stauffacher K, et al. The effects of inattentiveness and hyperactivity on posttraumatic stress symptoms: does a diagnosis of posttraumatic stress disorder matter? J Atten Disord. 2020;24(9):1246–1254.

- Harrington KM, Miller MW, Wolf EJ, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder comorbidity in a sample of veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(6):679–690.

- Kilpatrick DG, Resnick HS, Milanak ME, et al. National estimates of exposure to traumatic events and PTSD prevalence using DSM-IV and DSM-5 criteria. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(5):537–547.

- Goldstein RB, Smith SM, Chou SP, et al. The epidemiology of DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder in the United States: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(8):1137–1148.

- Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995;52(12):1048–1060.

- Kanady JC, Talbot LS, Maguen S, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia Reduces fear of sleep in individuals With posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(7):1193–1203.

- Talbot LS, Maguen S, Metzler TJ, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2014;37(2):327–341.

- Drake CL. The promise of digital CBT-I. Sleep. 2016;39(1):13–14.

- Schnurr PP. Focusing on trauma-focused psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder. Curr Opin Psychol. 2017;14:56–60.

- Hegberg NJ, Hayes JP, Hayes SM. Exercise intervention in PTSD: a narrative review and rationale for implementation. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:133.

- Logue MW, van Rooij SJH, Dennis EL, et al. Smaller hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder: a multisite ENIGMA-PGC study: subcortical volumetry results from posttraumatic stress disorder consortia. Biol Psychiatry. 2018;83(3):244–253.

- Bettmann JE, Prince KC, Ganesh K, et al. The effect of time outdoors on veterans receiving treatment for PTSD. J Clin Psychol. 2021;77(9):2041–2056.

- Kaushal N, Rhodes RE, Spence JC, Meldrum JT. Increasing physical activity through principles of habit formation in new gym members: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51(4):578–586.

- Carels RA, Burmeister JM, Koball AM, et al. A randomized trial comparing two approaches to weight loss: differences in weight loss maintenance. J Health Psychol. 2014;19(2):296–311.

- Zalta AK, Tirone V, Orlowska D, et al. Examining moderators of the relationship between social support and self-reported PTSD symptoms: a meta-analysis. Psychol Bull. 2021;147(1):33–54.

- Brewin CR, Andrews B, Valentine JD. Meta-analysis of risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed adults. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(5):748–766.

- Osuka Y, Jung S, Kim T, et al. Does attending an exercise class with a spouse improve long-term exercise adherence among people aged 65 years and older: a 6-month prospective follow-up study. BMC Geriatr. 2017;17(1):170.

- Youngstedt SD, Kline CE, Reynolds AM, et al. Bright light treatment of combat-related PTSD: a randomized controlled trial. Mil Med. 2022;187(3–4):e435–e444.

- Arkkukangas M, Söderlund A, Eriksson S, Johansson AC. One-year adherence to the Otago exercise program with or without motivational interviewing in community-dwelling older adults. J Aging Phys Act. 2018;26(3):390–395.

- Resnicow K, McMaster F. Motivational interviewing: moving from why to how with autonomy support. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9:19.

- Thakkar MM, Sharma R, Sahota P. Alcohol disrupts sleep homeostasis. Alcohol. 2015;49(4):299–310.

- Chakravorty S, Chaudhary NS, Brower KJ. Alcohol dependence and its relationship with insomnia and other sleep disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(11):2271–2282.

- McMillan KA, Asmundson GJG, Sareen J. Comorbid PTSD and social anxiety disorder: associations with quality of life and suicide attempts. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205(9):732–737.