by Ahmed Aboraya, MD, Dr.PH; Henry A. Nasrallah, MD; Daniel E. Elswick, MD; Ahmed Elshazly, MD; Nevine Estephan, MD; Dalia Aboraya, BA; Seher Berzingi; Josleen Chumbers; Aara Berzingi, BA; John Justice, MD; Jawad Zafar, DO; and Sheena Dohar, MD

Dr. Aboraya is Chief of Psychiatry at William R. Sharpe, Jr. Hospital, Clinical Professor of Psychiatry at West Virginia School of Osteopathic Medicine, and Adjunct Faculty with the School of Public Health West Virginia University, in Weston, West Virginia. Dr. Nasrallah is the Sydney Souers Professor and Chairman of the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neuroscience at Saint Louis University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri. Dr. Elswick is Associate Professor at West Virginia University in Morgantown, West Virginia. Mr. Elshazly is a second year resident at Atlanticare Regional Medical Center in Atlantic City, New Jersey. Dr. Estephan is Child Psychiatry Fellow at West Virginia University in Morgantown, West Virginia. Ms. Aboraya is with Ohio Northern University Law School in Ada, Ohio. Mr. Seher Berzingi and Mses. Chumbers and Sara Berzingi are researchers at West Virginia University in Morgantown, West Virginia. Dr. Justice is Medical Director of Sharpe Hospital in Weston, West Virginia. Drs. Zafar and Dohar are psychiatry residents at West Virginia University in Morgantown, West Virginia.

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2018;15(11–12):13–26

Abstract: The authors define measurement-based care (MBC) in psychiatry as the use of validated clinical measurement instruments to objectify the assessment, treatment, and clinical outcomes, including efficacy, safety, tolerability, functioning, and quality of life, in patients with psychiatric disorders. MBC includes two processes: routine assessments, such as measuring the severity of symptoms with rating scales, and the use of assessments in decision-making. MBC implementation was tested in the Texas Medication Algorithm Project and the German Algorithm Project and has been shown to improve patient outcomes. Even though more recent research has shown the many benefits of MBC compared to the usual care, MBC is still not the standard of care in psychiatric practice. This review article addresses the advantages of MBC, the barriers to implementing MBC in clinical practice, and the basic properties of MBC instruments. Recent developments in the 21st century that are expected to accelerate the adoption of MBC in clinical practice, including electronic health records, health information technology, and the development of the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP) as an MBC tool, will be reviewed. The authors recommend including MBC in psychiatry residency training to promote its use in future generations.

Keywords: Measurement-based care (MBC), Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP), assessment, psychopathology, assessment tool, rating scale, reliability, validity, outcomes measures, clinical trial

In science, measurement is defined as “rules for assigning numbers to objects in such a way as to represent quantities of attributes.”1 Scientific measurements cannot be valid if they are not reliable. Attributes, reliability, and validity are all crucial to conducting any research. Once scientifically credible measurements are created, testing hypotheses and conducting meaningful clinical trials become possible, leading to advances in science and medicine.

Measurement in psychiatry can be traced back to 1825 when a royal commission was issued to enumerate and measure the “condition of the insane” in the kingdom of Norway. Professor Holst published the results of the survey, which was repeated in 1835 and 1845. The survey results are fascinating and described patients with “mania, melancholia, dementia, idiotia, blind in one eye or two eyes, deaf, dumb, and lepers,” classified by sex and by rural and urban districts.2 Major advances in science are preceded by breakthroughs in measurement methods. This was demonstrated in the field of psychology by the flood of research following the development of intelligence tests and the intelligence quotient (IQ) in 1912.1

The term measurement-based care (MBC) was coined by Trivedi in 2006 and was defined as “the routine measurement of symptoms and side effects at each treatment visit and the use of a treatment manual describing when and how to modify medication doses based on these measures.”3 Other authors had similar definitions: Harding defined MBC as “enhanced precision and consistency in disease assessment, tracking, and treatment to achieve optimal outcomes,”4 Arbuckle defined MBC as “a step-by-step approach for assessing, treating, reviewing outcomes and revising treatment in managing medical diseases,”5 and Fortney defined MBC as “the systematic administration of symptom rating scales and use of the results to drive clinical decision making at the level of the individual patient.”6 Our working definition of MBC in psychiatry is “the use of validated clinical measurement instruments to objectify the assessment, treatment and clinical outcomes, including efficacy, safety, tolerability, functioning, and quality of life, in patients with psychiatric disorders.”

MBC refers to two processes: routine assessments, such as measuring the severity of symptoms with rating scales, and the use of assessments in decision-making. The development of rating scales and diagnostic interview schedules during the second half of the 20th century, as well as their use in psychiatric research and clinical trials, was an important catalyst for the development and implementation of MBC. With the publications of Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM-III) in 1980 and its widespread use worldwide, psychiatric research and clinical trials flourished as geneticists, pharmacologists, and neuroscientists became research partners with investigative psychiatrists.7 More clinical trials were conducted to assess the efficacy and safety of the new psychotropic medications all over the world.8–16 With the availability of rating scales and standardized diagnostic interviews, the Texas Medication Algorithm Project (TMAP) and the German Algorithm Project (GAP) tested the implementation of MBC in outpatient and inpatient clinical settings and have shown that MBC can positively impact patient outcomes.17–19 Even though the term measurement-based care is relatively new in psychiatric literature, it has been an integral component of randomized, clinical trials for decades.20

The other popular and common method of caring for patients is the “standard” or “usual” care that has been provided by clinicians daily for centuries. Usual standard care (USC) for patients involves the same two components of MBC: assessment and decision-making. Clinicians, by training, assess psychopathology and its severity and make decisions based on their assessment, without using rating scales or standardized diagnostic interviews. In 1933, Hardcastle et al studied the present condition of the first 100 patients (adults and children) who attended the Department of Psychological Medicine at Guy’s Hospital in London in 1931. Although clinicians in 1933 did not have or use the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) or other scales we have today, they evaluated the patients and grouped them into four main groups: much improved, improved, unchanged, or worse. Based on their evaluations, they made decisions to admit or treat patients accordingly. The Hardcastle study was published in the Journal of Mental Science in 1934.21 In the same journal and during the same year, Lewis22 published a 102-page monograph describing in great detail the symptoms and signs of 61 cases of “depressive state,” all examined and treated by Lewis between the years 1928 and 1929 in the Maudsley Hospital in London, England. One might make the case that psychiatrists at Guy’s and Maudsley’s hospitals in 1934 had more expertise in psychopathology assessment than today’s psychiatrists because one of the unintended consequences of the DSM era is the limitation of psychopathology training according to DSM and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) criteria.23

Recent research has shown the superiority of MBC compared to USC in improving patient outcomes.6,24–26 A recent, well-designed, blind-rater, randomized trial by Guo et al17 showed that MBC, per se, is more effective than USC in achieving response and remission and lowering the time to response and remission. Given the evidence of the benefits of MBC in improving patient outcomes, an important question arises: Why has MBC not yet been established as the standard of care in clinical practice?

This review article addresses the advantages of MBC, the barriers to implementing MBC in clinical practice, and important contemporary developments in the 21st century that are expected to accelerate the adoption of MBC in clinical practice.

Advantages of MBC

Research over the past 20 years has shown that MBC improves the quality of patient care, and leaders in the mental health field have been calling for the integration of MBC into routine care.6 Compared to the usual care, MBC has been shown to do the following:

- Improve psychotherapy outcomes6

- Monitor symptom reduction in patients with psychiatric disorders, such as anxiety, depression, and bipolar27–29

- Identify patients who are improving and those who are deteriorating6,30,31

- Improve role functioning, satisfaction with care, quality of care, and quality of life24,29,32

- Enhance the therapeutic relationship and communication between providers and patients6

- Improve collaborative care efforts among providers24,32

- Improve the accuracy of clinical judgment4,33

- Close the gap between research and practice, and move psychiatry into the mainstream of medicine4

- Enhance the clinician’s decision-making process24,26

- Enhance individualized treatment34

- Be transdiagnostic and transtheoretical24

- Be feasible to implement on a large scale3,35–38

Barriers to MBC

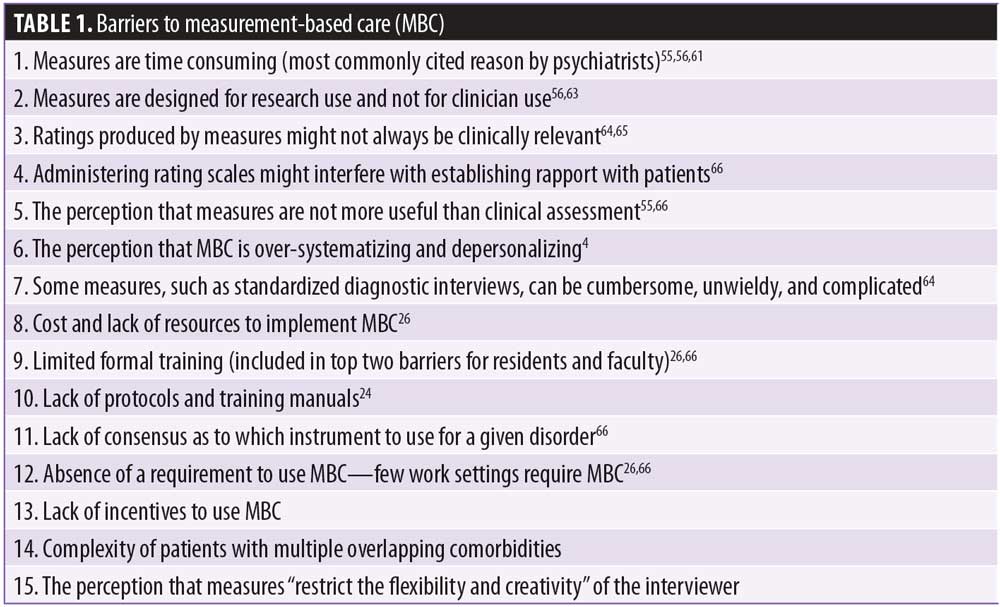

Even though recent research has shown the many benefits of MBC compared to USC, MBC is still not the standard of care in clinical settings, and a small proportion of clinicians use outcome assessments.4,39 Many psychiatric measures with good psychometric properties have been developed and tested over the past decades (e.g., standardized diagnostic interviews, rating scales, and self-rating scales).40–54 However, most of these measures are used in research and clinical trials and not in clinical settings. A study by Hatfield26 reported that 37.1 percent of clinicians use some form of outcome assessments, and 62.9 percent do not use any outcome measures. Zimmerman55 reported that more than 80 percent of psychiatrists indicated they did not routinely use scales to monitor outcome when treating depression. In a survey of psychiatric practitioners, Nasrallah56 reported that 98 percent of psychiatrists indicated they do not use any of the four clinical rating scales routinely used in clinical trials and are required for the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of psychiatric medications. These four scales are 1) Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), 2) Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS), 3) HAM-D, and 4) Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS). The vast majority of the surveyed participants attributed their avoidance of rating scales to “lack of time.” Many other authors have noted that clinicians do not use standardized scales in clinical practice.57–63 Barriers to implementing MBC are summarized in Table 1.

Additionally, theoretical orientation was described as a potential barrier for insight-oriented therapists, who were less likely than cognitive or behavioral therapists to use outcome measures.39 However, a recent article by Scott24 demonstrated that clinicians can implement MBC regardless of their theoretical orientation or training background.

Implementation of MBC

To encourage clinicians to use measures in clinical care decisions, measures should have the following basic properties:

- Efficient (Measures should be brief and not time-consuming to the clinician.4,67 A rating scale completed by the clinician should take no more than a few minutes to administer.)

- Established as reliable and valid4

- User-friendly and a reflection of what clinicians do in clinical settings67

- Brief (Self-rating scales completed by patients should take no more 2–3 minutes to complete) and simple (Directions should be easy to follow to improve patient willingness to take the test at each follow up visit.)68

- Clinically meaningful and useful, covering the criteria and symptom domains of the disorder67

- Clinically relevant to decision-making65

- Easily extractable and not embedded in progress notes6

- Sensitive to changes induced by medications or psychotherapy.69

Development of the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP) and the SCIP scales as an MBC tool

After Ahmed Aboraya (first author) finished his master’s and doctoral degrees at Johns Hopkins University in 1991, he started his psychiatry residency training with a determination to use psychiatric measures in clinical settings. Disappointed after 10 years of trying to use almost all of the relevant existing scales and standardized diagnostic interviews for adult psychiatric disorders, Aboraya concluded that existing measures were not practical for use in the real world of psychiatric practice. Consequently, he embarked on developing the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP) as a tool for clinicians in real clinical settings for assessment and decisions-making. In other words, the SCIP was designed from the outset as an MBC tool. The SCIP was tested in an international, multisite study in three countries (United States, Canada, and Egypt) between the years 2000 and 2012. The total sample size, including all sites, was 1,004 subjects, making the SCIP project the largest validity and reliability study to be conducted on diagnostic interviews in psychiatry.47,48,64 The details of the design of the SCIP project were published in 2014.48 In addition to being the only tool designed from the outset for use in MBC, the SCIP has two unique advantages: the development of comprehensive and reliable items measuring psychopathology and the creation of reliable and validated SCIP scales for adult psychiatric disorders.

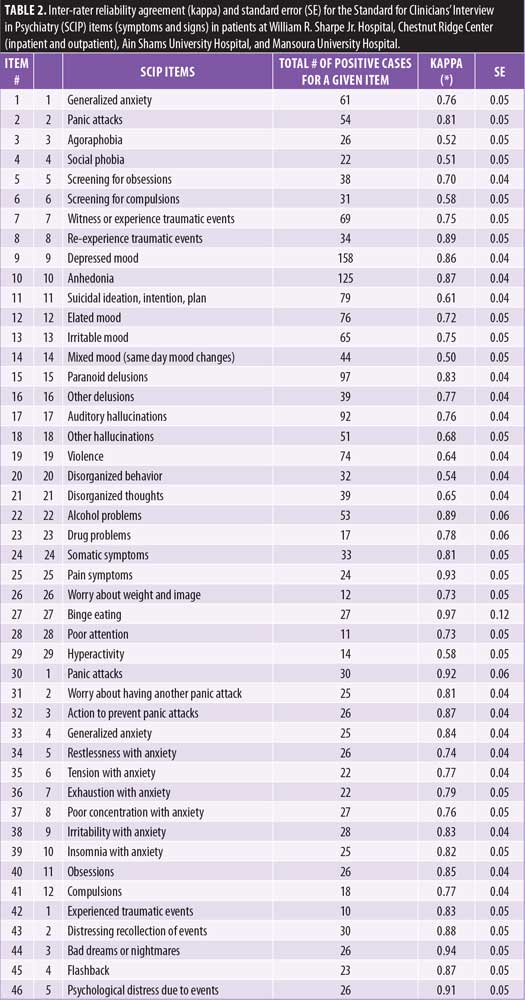

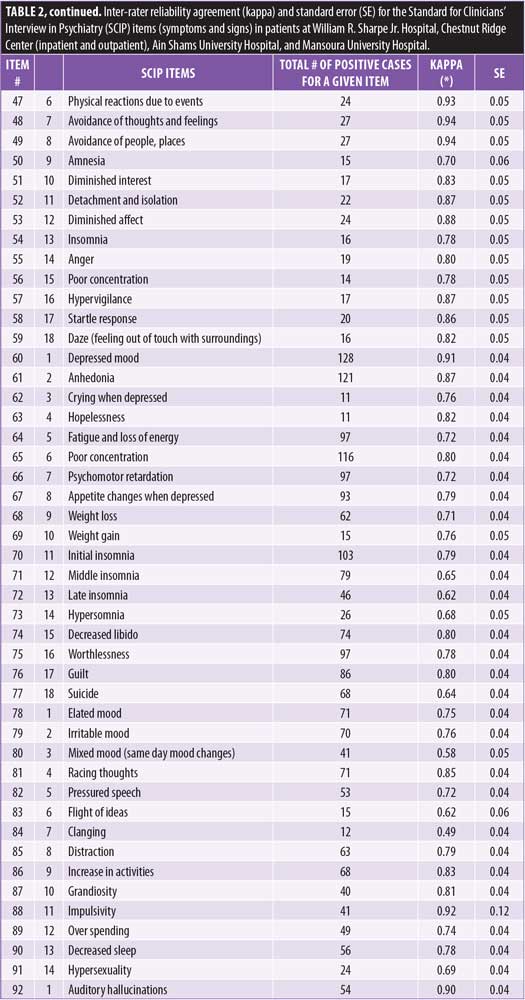

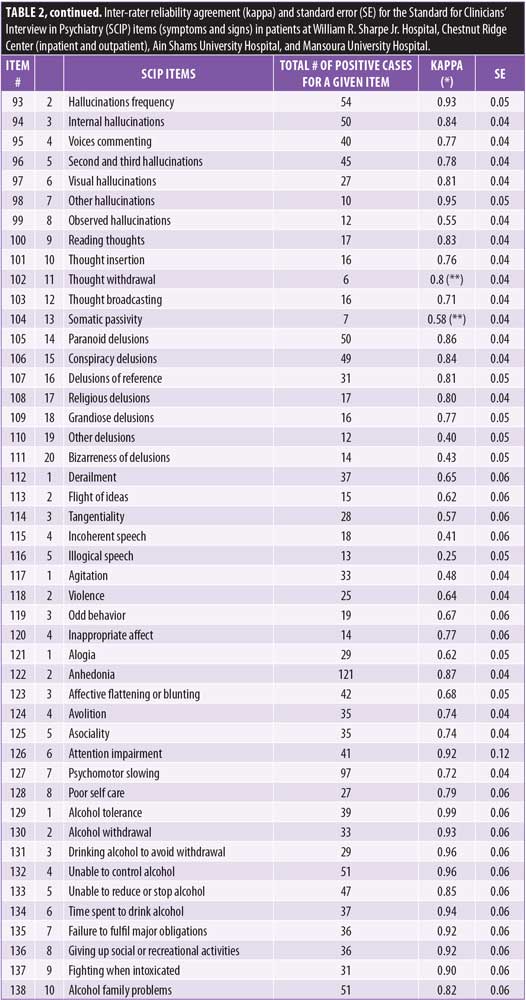

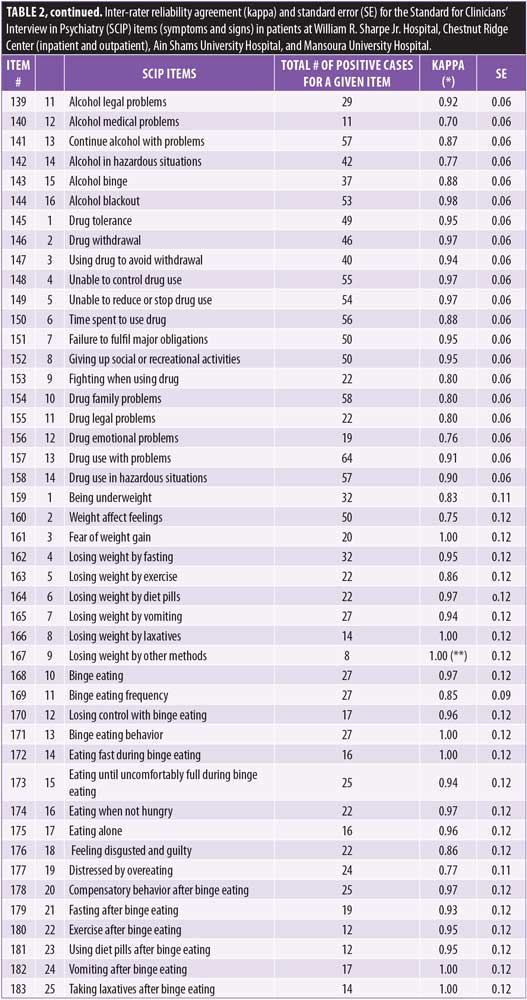

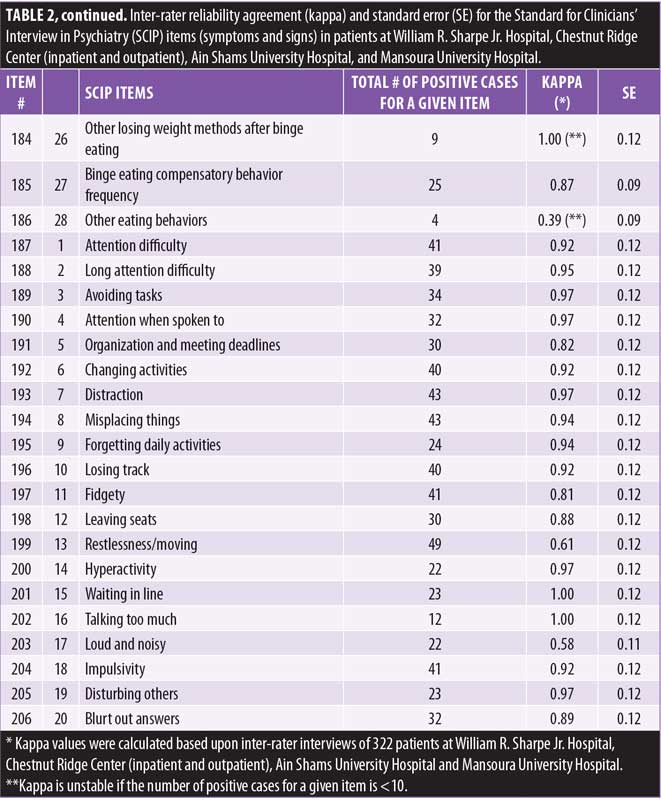

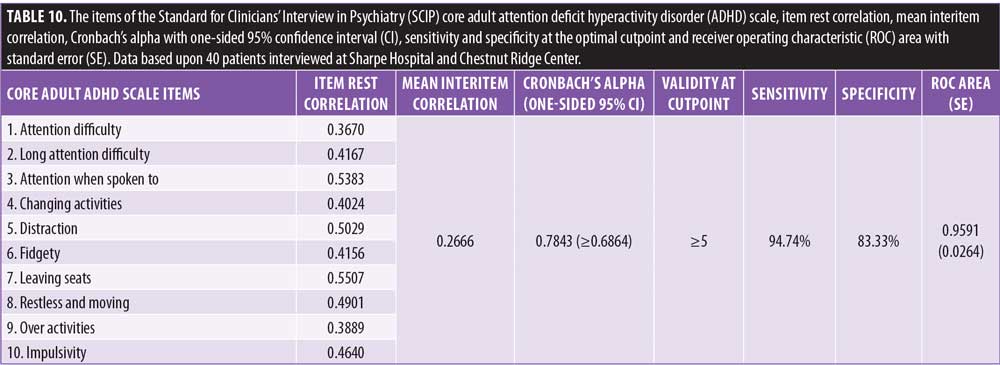

The development of reliable psychopathology items. Inter-rater reliability (Kappa) of the SCIP was measured on 150 items covering anxiety, panic, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, mania, psychosis, disorganized behavior, negative symptoms, alcohol, and drug psychopathology domains.48 To calculate stable Kappa for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and eating disorders, an additional 40 young and predominantly female patients were interviewed at William R. Sharpe, Jr. Hospital and Chestnut Ridge Center by at least two interviewers at the same time (to establish inter-rater reliability). The mean patient age was 35, with 68 percent being female, 90 percent being white, and 73 percent completing at least 12 years of education. If the patient was interviewed by three interviewers (i.e., A, B, C), a comparison was made between interviewer A and B, A and C, and B and C. A total of 75 comparisons allowed the calculation of stable Kappa for ADHD and eating disorders. Table 2 shows inter-rater reliability agreement (Kappa) and the standard error for 206 psychopathology items based on the interviews of 322 patients from William R. Sharpe Jr. Hospital, Chestnut Ridge Center (inpatient and outpatient), Ain Shams University Hospital, and Mansoura University Hospital. The mean patient age was 33, with 45 percent being female, 97 percent being white, and 63 percent completing at least 12 years of education. Five items (Item Numbers 102, 104, 167, 184, and 186) had unstable Kappa, and 201 items had stable Kappa. Out of 201 items with stable Kappa, 165 items (82%) had satisfactory agreement (?>0.7), 30 items (15%) had fair agreement (?=0.5 to 0.7), and 6 items (3%) had poor agreement (?<0.5).

In 1992, Nancy Andreasen, a renowned researcher, stressed the importance of establishing reliability at the level of individual symptoms and signs. Creating reliable psychological dimensions requires reliability of the items measuring individual symptoms and signs. The absence of valid and reliable symptoms was the main limiting factor in creating dimensional measures in the past.70 The SCIP study removed this major obstacle by creating reliable symptoms and signs for 206 psychopathology items, which paved the way for the creation of reliable and valid SCIP dimensions and scales.

The development of reliable and valid SCIP dimensions and scales for adult psychiatric disorders. The SCIP dimensions and scales were created based on the interviews of 700 patients, 670 of whom were from William R. Sharpe Jr. Hospital in Weston, West Virginia, and 30 of whom were from at Chestnut Ridge Center in Morgantown, West Virginia. Mean patient age was 34, with 59 percent being male, 95 percent being white, and 66 percent completing at least 12 years of education. Patients were evaluated and diagnosed by the attending psychiatrist. We evaluated and treated each patient from admission to discharge, using all available data, including information from previous hospitalizations and family members, labs, psychological testing, and diagnostic schedules, as needed, to reach the final diagnoses.

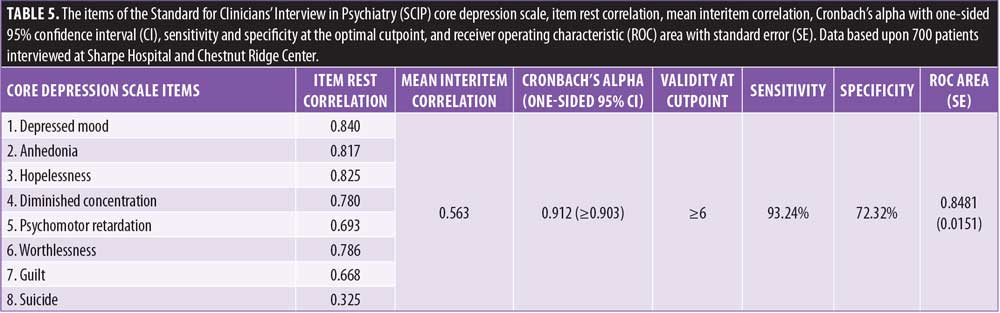

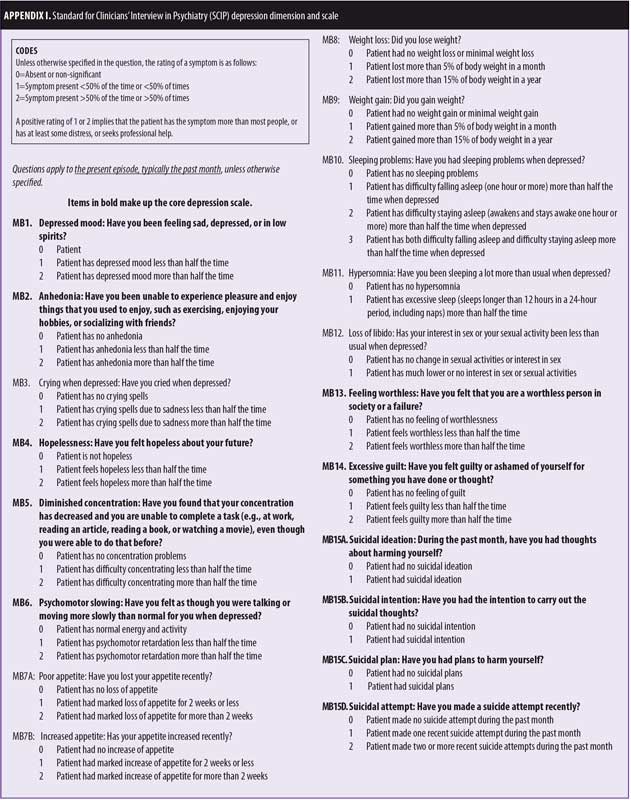

The initial items of the SCIP dimensions were formulated based upon the DSM and ICD criteria and expert opinions. The sensitivity and specificity of the initial dimensions were calculated against the psychiatric diagnosis, as described above. Rules for shortening the lengthy initial dimensions and creating the final SCIP dimensions included removing items with low prevalence, low sensitivity, or low item-rest correlation (<0.4). The reliability and validity of the remaining items were recalculated with repetitive iterations. The sensitivity and specificity of the final dimensions were approximately equal to the sensitivity and specificity of the initial dimensions. Appendix I shows the initial depression dimension, which has 15 symptoms and signs of depression. Three items not covered in DSM-5—crying when depressed, feeling hopeless, and reduced sexual desire—were included in the initial depression dimension based on the recommendations and use by experts and clinicians for decades, even before the existence of the DSM.23 The sensitivity and specificity of the initial depression scale were 93.24 percent and 74.15 percent, respectively. Following the rules of creating the SCIP scales, the final core depression scale had eight items with 93.24-percent sensitivity and 72.32-percent specificity.

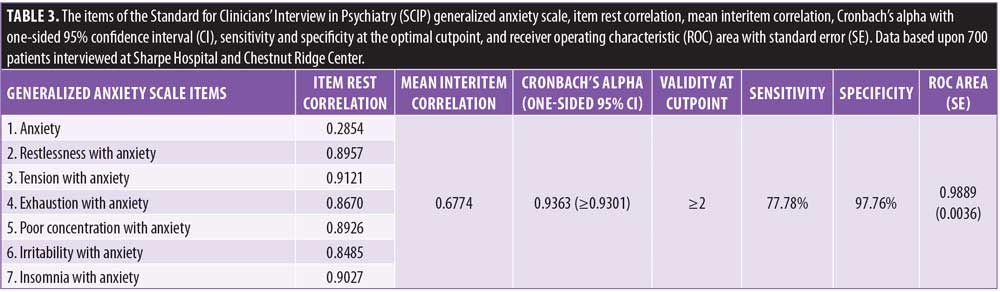

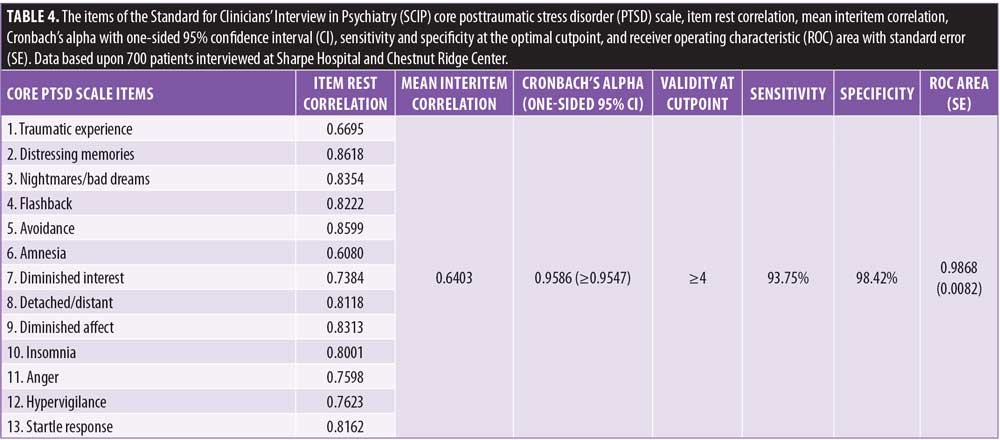

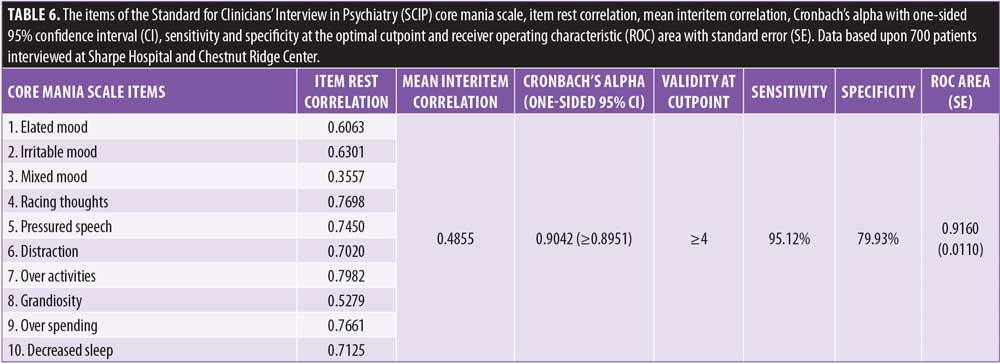

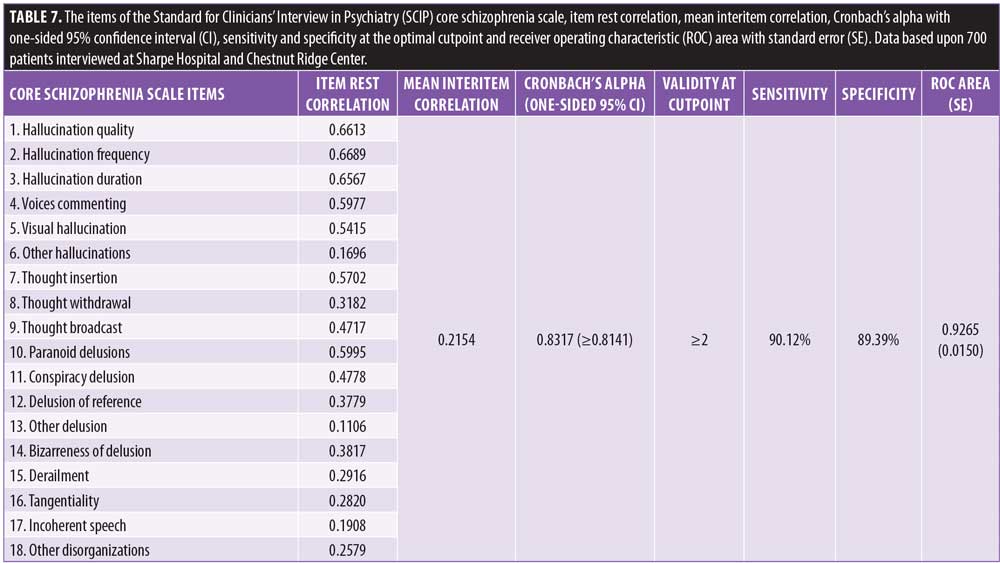

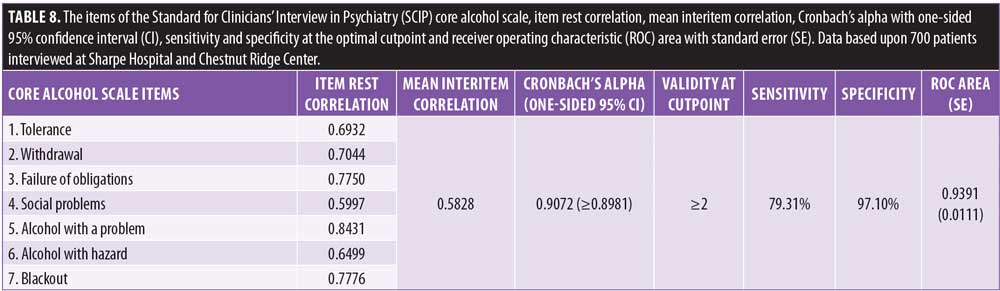

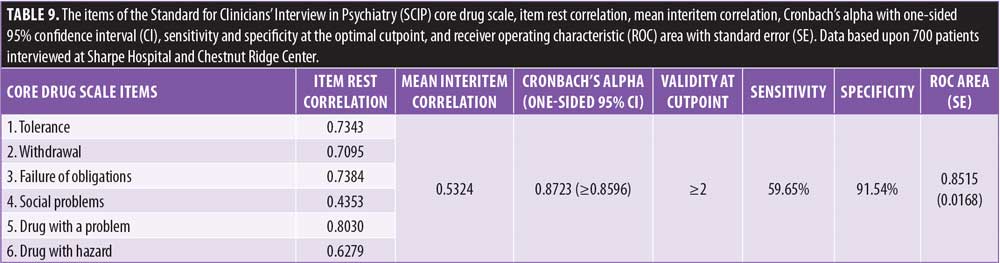

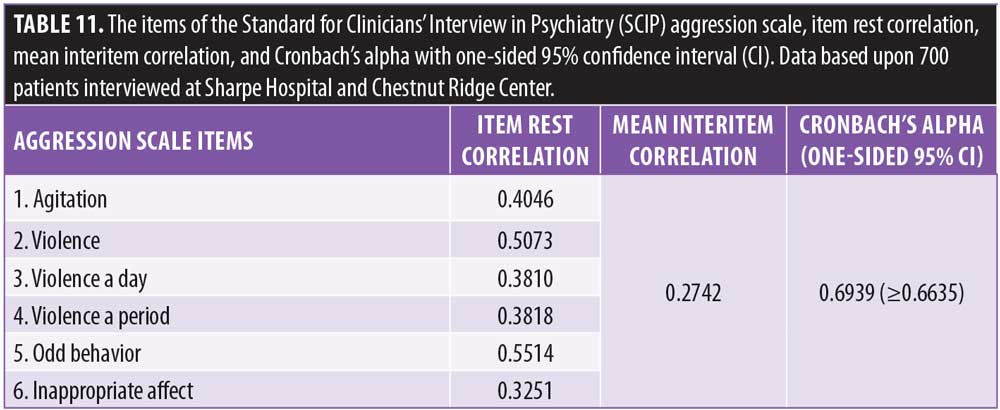

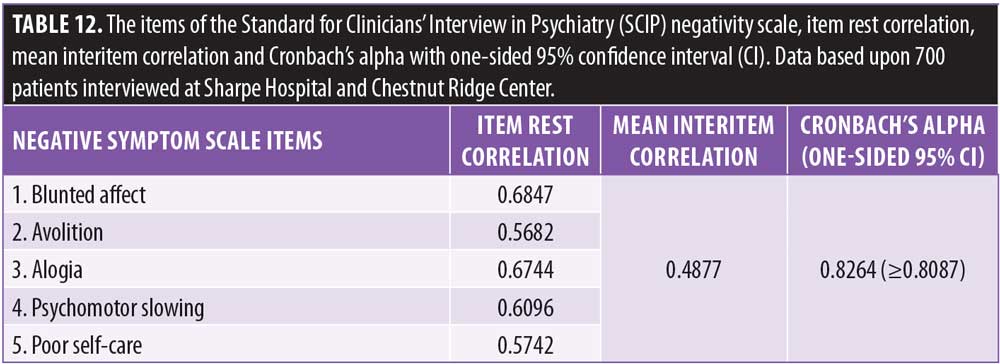

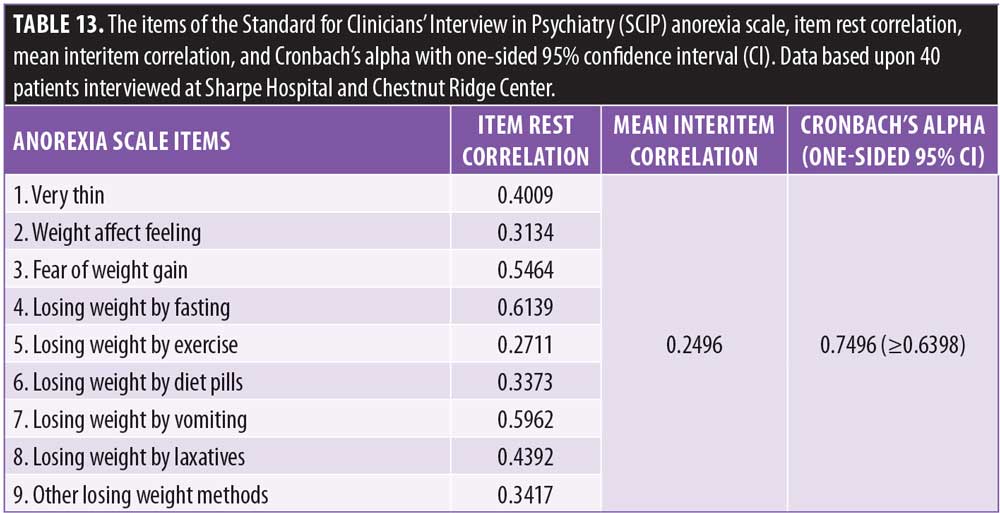

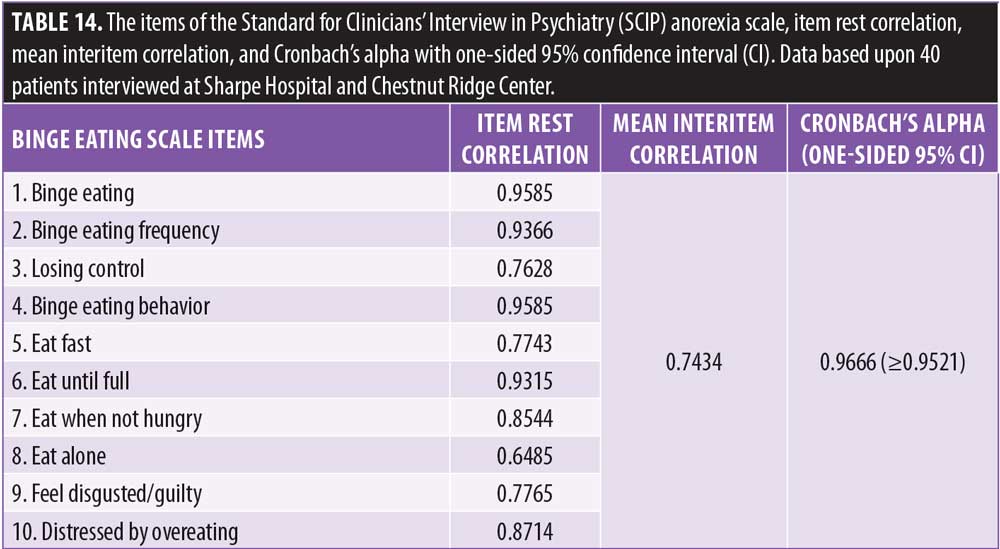

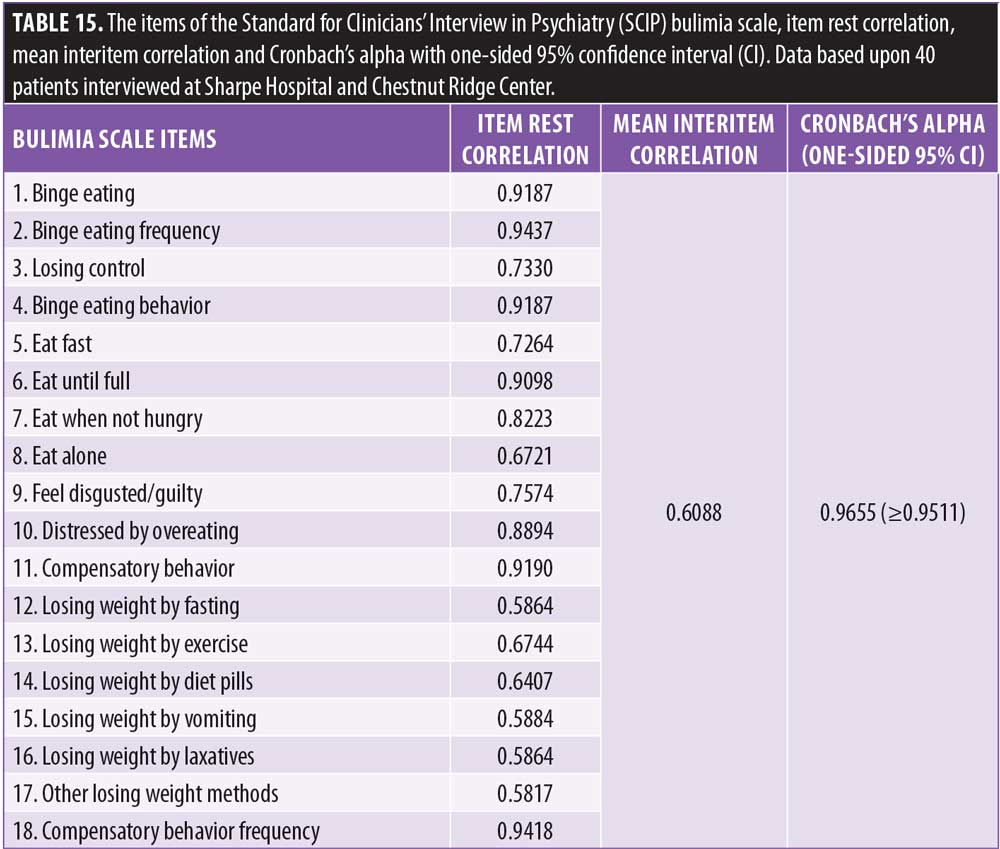

Based upon reliable psychopathology items, the SCIP is the only diagnostic tool that has 18 inherent rating scales for the following domains: generalized anxiety, obsessions, compulsion, posttraumatic stress, depression, mania, delusions, hallucinations, disorganized thoughts, aggression, negative symptoms, alcohol use, drug use, attention deficit, hyperactivity, anorexia, binge-eating, and bulimia. Each of the SCIP rating scales takes 2 to 5 minutes to complete. The SCIP rating scales meet the criteria for MBC because they are efficient, reliable, valid, reflect how clinicians assess psychiatric disorders, and are relevant to decision-making. These unique properties make the SCIP ideal as an MBC tool. Tables 3 to 15 show the items included in the SCIP scales, item rest correlation, mean interitem correlation, Cronbach’s alpha with one-sided 95-percent confidence interval (CI), sensitivity and specificity at the optimal cutpoint, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) area with standard error. All of the SCIP scales have been validated with the exception of the OCD and eating disorders scales. Aboraya, Henry Nasrallah, and Daniel Elswick (the first three authors of this article) are currently writing a book that describes the advantages and disadvantages of the SCIP scales and other existing scales in the literature.

Recent Developments Affecting MBC

Electronic health records. Electronic health records (EHR) are being used across clinical settings, from big academic institutions to solo practices. The United States Federal government has given financial incentives to solo practitioners to use EHR, and most academic institutions use advanced EHR.71 Once MBC tools are identified, they can be uploaded to the EHR and be readily available for clinicians to use. The use of EHR should facilitate the implementation of MBC.4

Health information technology. Advances in health information technology, such as software programs, handheld devices, web-based training, and videos, should facilitate clinician training and use of MBC tools.6,71,72 Currently, psychiatrists record diagnosis, mental status, and other clinical aspects in a loose narrative outline, making it difficult to measure or compare outcomes of patients that have been assessed by different clinicians.67 This current practice will be outdated in the near future with the implementation of MBC. With the right software and integrated EHR, clinicians should be able to efficiently record a rating scale, calculate the scale score, compare scores on the same scale over time, draw graphs, and do analyses.

Training psychiatry residents and clinicians in MBC. Lack of training was listed among the top two barriers to using MBC by psychiatry residents and faculty.26,66 In addition, lack of consensus as to which instrument to use was another barrier due to the availability of many measures.66 One important place to promote the use of MBC is in psychiatry residency programs. Currently, no specific requirements exist to evaluate training on the use of MBC during residency.73 A new psychiatry subcompetency for MBC could be added to the existing 22 psychiatry subcompetencies included in the Psychiatry Milestone Project Initiative by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN).74 Psychiatry residents could learn and progress using the new MBC subcompetency from Level 1 (basic knowledge of psychiatric measures) to Levels 4 and 5 (the ability to use the appropriate measures for making decisions). Arbuckle et al5 implemented a curriculum in MBC for depression in a psychiatric resident clinic and found that MBC was feasible and improved depression screening and monitoring. Aboraya is developing an MBC manual and a didactic seminar for psychiatry residents, using the SCIP scales and other scales for personality disorders and cognitive disorders. A pilot study for implementing MBC for adult psychiatric disorders at the West Virginia University residency program and other programs is underway. If psychiatry residents are trained in MBC, they might potentially practice MBC for the rest of their careers. There is also urgent need to train faculty and clinicians in MBC through continuing medical education (CME) workshops.4 Aboraya, Nasrallah, and Elswick are planning MBC workshops to train clinicians and psychiatry residents on how to choose the right scale or instrument for each individual patient.

Discussion

In 1961, when Robert Spitzer developed the Mental Status Schedule, the first published structured interview in the United States,75 the New York Post published an article in 1963 that stated “a young doctor at Columbia University’s New York State Psychiatric Institute has developed a tool which may become the psychiatrist’s thermometer and microscope and X-ray machine rolled into one.”76 Five decades later, many might say this statement is still accurate—measures in psychiatry could be considered the equivalent of a thermometer and a stethoscope to a physician. No measure, scale, or diagnostic interview will ever replace a seasoned, experienced clinician who has been evaluating and treating real patients for years. MBC is not intended to replace clinical judgment and cannot substitute for an observant and caring clinician.4 Just as thermometers, stethoscopes, and lab tests help other types of physicians reach accurate diagnoses and provide appropriate management, the use of MBC by psychiatrists has the potential to improve the accuracy of diagnoses and improve the outcomes of care. In essence, MBC aims to get the diagnosis and management right as often and as quickly as possible.4

The use of scientific rules and expert input for the creation of efficient and validated SCIP scales does not minimize the importance of the psychopathology items not included in the final SCIP scales. The core depression scale of the SCIP does not include questions on reduced sexual drive, sleep, or appetite changes. Clinicians need to inquire about these important items because they can impact which medications will be most effective for individual patients. In teaching and implementing MBC, clinicians should stress the importance of comprehensive psychopathological assessment to avoid the trap of limiting psychopathology education to specific diagnostic criteria or certain scales.

Conclusion

Recent studies have shown that the cost of MBC implementation is minimal and the benefits are significant for patients, providers, and payers.6 The advantages of MBC outweigh the challenges to its implementation.77 Moreover, many payers and accreditation organizations are requiring the use of MBC in psychiatric practice. We believe it is better for healthcare providers to develop their own MBC tools than to have outcome measures imposed on them by payers and/or regulators.6 The three main ingredients for MBC implementation, namely measures, EHR, and health information technologies, already exist. We believe now is the time to employ MBC into standard practice, and published research supports this.20 The onus lies on mental health providers to implement MBC.

References

- Nunnally JC. Psychometric Theory. New York McGraw-Hill. 1978.

- Holst P. On the statistics of the insane, blind, deaf and dumb, and lepers, of Norway. J Royal Stat Soc. 1852;15:250–256.

- Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:28–40.

- Harding KJ, Rush AJ, Arbuckle M, et al. Measurement-based care in psychiatric practice: a policy framework for implementation. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72:1136–1143.

- Arbuckle MR, Weinberg M, Kistler SC, et al. A curriculum in measurement-based care: screening and monitoring of depression in a psychiatric resident clinic. Acad Psychiatry. 2013;37:317–320.

- Fortney JC, Unutzer J, Wrenn G, et al. A tipping point for measurement-based care. Psychiatr Serv. 2016:appips201500439.

- McHugh PR. Striving for coherence: psychiatry’s efforts over classification. JAMA. 2005;293:2526–2528.

- Fleischhacker WW, Gopal S, Lane R, et al. A randomized trial of paliperidone palmitate and risperidone long-acting injectable in schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:107–118.

- Fleischhacker WW, McQuade RD, Marcus RN, et al. A double-blind, randomized comparative study of aripiprazole and olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:510–517.

- Kane JM, Eerdekens M, Lindenmayer JP, et al. Long-acting injectable risperidone: efficacy and safety of the first long-acting atypical antipsychotic. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1125–1132.

- Kane JM, Skuban A, Ouyang J, et al. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled phase 3 trial of fixed-dose brexpiprazole for the treatment of adults with acute schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2015;164:127–135.

- Kane JM, Zukin S, Wang Y, et al. Efficacy and safety of cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: results from an international, Phase III clinical trial. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35:367–373.

- Nasrallah HA, Silva R, Phillips D, et al. Lurasidone for the treatment of acutely psychotic patients with schizophrenia: a 6-week, randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Psychiatr Res. 2013;47:670–677.

- Durgam S, Cutler AJ, Lu K, et al. Cariprazine in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: a fixed-dose, phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:e1574–1582.

- Durgam S, Starace A, Li D, et al. An evaluation of the safety and efficacy of cariprazine in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: a phase II, randomized clinical trial. Schizophr Res. 2014;152:450–457.

- Meltzer HY, Risinger R, Nasrallah HA, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of aripiprazole lauroxil in acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76:1085–1090.

- Guo T, Xiang YT, Xiao L, et al. Measurement-based care versus standard care for major depression: a randomized controlled trial with blind raters. Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:1004–1013.

- Crismon ML, Trivedi M, Pigott TA, et al. The Texas Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on Medication Treatment of Major Depressive Disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60:142–156.

- Ricken R, Wiethoff K, Reinhold T, et al. Algorithm-guided treatment of depression reduces treatment costs–results from the randomized controlled German Algorithm Project (GAPII). J Affect Disord. 2011;134:249–256.

- Rush AJ. Isn’t it about time to employ measurement-based care in practice? Am J Psychiatry. 2015;172:934–936.

- Hardcastle D. A follow-up study of one hundred cases made for the department of psychological medicine, Guy’s hospital. Journal of Mental Science. 1934;80:536–549.

- Lewis A. Melancholia: A clinical survey of depressive states. Journal of Mental Science. 1934;80:277–378.

- Kendler KS. The phenomenology of major depression and the representativeness and nature of DSM criteria. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:771–780.

- Scott K, Lewis CC. Using measurement-based care to enhance any treatment. Cogn Behav Pract. 2015;22:49–59.

- Lambert MJ. Psychotherapy outcome and quality improvement: introduction to the special section on patient-focused research. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:147–149.

- Hatfield DR, Ogles BM. Why some clinicians use outcome measures and others do not. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34:283–291.

- Roy-Byrne P, Craske MG, Sullivan G, et al. Delivery of evidence-based treatment for multiple anxiety disorders in primary care: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;303:1921–1928.

- Simon GE, Ludman EJ, Bauer MS, et al. Long-term effectiveness and cost of a systematic care program for bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:500–508.

- Bauer MS, McBride L, Williford WO, et al. Collaborative care for bipolar disorder: Part II. Impact on clinical outcome, function, and costs. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:937–945.

- Hatfield D, McCullough L, Frantz SH, Krieger K. Do we know when our clients get worse? an investigation of therapists’ ability to detect negative client change. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2010;17:25–32.

- Hannan C, Lambert MJ, Harmon C, et al. A lab test and algorithms for identifying clients at risk for treatment failure. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:155–163.

- Katon WJ, Lin EH, Von Korff M, et al. Collaborative care for patients with depression and chronic illnesses. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2611–2620.

- Sapyta J, Riemer M, Bickman L. Feedback to clinicians: theory, research, and practice. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61:145–153.

- Trivedi MH, Daly EJ. Measurement-based care for refractory depression: a clinical decision support model for clinical research and practice. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88 Suppl 2:S61–71.

- Unutzer J, Chan YF, Hafer E, et al. Quality improvement with pay-for-performance incentives in integrated behavioral health care. American journal of public health and the nation’s health. 2012;102:e41–45.

- Pomerantz AS, Kearney LK, Wray LO, et al. Mental health services in the medical home in the Department of Veterans Affairs: factors for successful integration. Psychol Serv. 2014;11:243–253.

- Johnson-Lawrence V, Zivin K, Szymanski BR, et al. VA primary care-mental health integration: patient characteristics and receipt of mental health services, 2008–2010. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:1137–1141.

- Sachs GS. Strategies for improving treatment of bipolar disorder: integration of measurement and management. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2004:7–17.

- Hatfield DO, B. The use of outcome measures by psychologists in clinical practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004;35:485–491.

- WHO. Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry Manual. Geneva, World Health Organization; 1994.

- WHO. Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry Glossary. Geneva, World Health Organization; 1994.

- WHO. Compsite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI). Geneva World Health Organization; 1990.

- Wing JK, Babor T, Brugha T, et al. SCAN. Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:589–593.

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59(Suppl 20):22–33;quiz 34–57.

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). I: History, rationale, and description. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:624–629.

- Williams JB, Gibbon M, First MB, et al. The Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID). II. Multisite test-retest reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:630-636.

- Aboraya A. The validity results of the Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP). Schizophrenia Bull. 2015;41:S103–S104.

- Aboraya A, El-Missiry A, Barlowe J, et al. The reliability of the standard for clinicians’ interview in psychiatry (SCIP): a clinician-administered tool with categorical, dimensional and numeric output. Schizophr Res. 2014;156:174–183.

- Hamilton M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56–62.

- Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:

261–276. - Overall JE, Gorham DR. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS): recent developments in ascertainment and scaling. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1988;24:97–99.

- Goodman WK, Price LH, Rasmussen SA, et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. I. Development, use, and reliability. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:1006–1011.

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961;4:561–571.

- Zimmerman M, Posternak MA, McGlinchey J, et al. Validity of a self-report depression symptom scale for identifying remission in depressed outpatients. Compr Psychiatry. 2006;47:185–188.

- Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB. Why don’t psychiatrists use scales to measure outcome when treating depressed patients? J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:1916–1919.

- Nasrallah H. Long overdue: measurement-based psychiatric practice. Current Psychiatry. 2009;8:14–16.

- Zimmerman M. Measuring outcome in clinical practice. Psychiatric Times. 2014;31:28.

- Duffy FF, Chung H, Trivedi M, et al. Systematic use of patient-rated depression severity monitoring: is it helpful and feasible in clinical psychiatry? Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1148–1154.

- Gilbody SM, House AO, Sheldon TA. Psychiatrists in the UK do not use outcomes measures. National survey. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:101–103.

- Bastiaens L. Poor practice, managed care, and magic pills: have we created a mental health monster? Psychiatric Times. 2011;28:1–4.

- Aboraya A. Use of structured interviews by psychiatrists in real clinical settings: results of an open-question survey. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6:24–28.

- Rettew DC, Lynch AD, Achenbach TM, et al. Meta-analyses of agreement between diagnoses made from clinical evaluations and standardized diagnostic interviews. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2009;18:169–184.

- Busner J, Kaplan SL, Greco NT, Sheehan DV. The use of research measures in adult clinical practice. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2011;8:19–23.

- Aboraya A, Nasrallah H, Muvvala S, et al. The Standard for Clinicians’ Interview in Psychiatry (SCIP): a clinician-administered tool with categorical, dimensional, and numeric output-conceptual development, design, and description of the SCIP. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2016;13:31–77.

- Aboraya A, Nasrallah HA. Perspectives on the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS): Use, misuse, drawbacks, and a new alternative for schizophrenia research. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2016;28:125–131.

- Arbuckle MR, Weinberg M, Harding KJ, et al. The feasibility of standardized patient assessments as a best practice in an academic training program. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:209–211.

- Roy-Byrne P, Dagadakis C, Ries R, et al. A psychiatrist-rated battery of measures for assessing the clinical status of psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 1995;46:347–352.

- Zimmerman M, McGlinchey JB. Depressed patients’ acceptability of the use of self-administered scales to measure outcome in clinical practice. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2008;20:125–129.

- Baer L. Handbook of Clinical Rating Scales and Assessment in Psychiatry and Mental Health. Boston: Humana Press; 2015.

- Andreasen NC, Flaum M, Arndt S. The Comprehensive Assessment of Symptoms and History (CASH). An instrument for assessing diagnosis and psychopathology. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:615–623.

- Blumenthal D. Stimulating the adoption of health information technology. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1477–1479.

- Long N. Closing the gap between research and practice—the importance of practitioner training. Clin Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;13:187–190.

- Baker M. Measurement-based care and psychiatric education: are we doing enough? Psychiatric News. 2015;50.

- The Psychiatry Milestone Project Initiative by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education and American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology. 2015. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/PsychiatryMilestones.pdf. Accessed 1 Dec 2018.

- Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Burdock EI, Hardesty AS. The mental status schedule: rationale, reliability and validity. Compr Psychiatry. 1964;5:384–395.

- Spitzer RL. Psychiatric diagnosis: are clinicians still necessary? Compr Psychiatry. 1983;24:399–411.

- Valenstein M, Adler DA, Berlant J, et al. Implementing standardized assessments in clinical care: now’s the time. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1372–1375.