by Leonor Moreira Abreu, MD, MSc, and João Gama Marques, MD, MSc, PhD

Dr. Moreira Abreu and Prof. Gama Marques are with Clínica Universitária de Psiquiatria e Psicologia Médica, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade de Lisboa in Lisbon, Portugal. Prof. Gama Marques is with Consulta de Esquizofrenia Resistente, Hospital Júlio de Matos, Centro Hospitalar Psiquiátrico de Lisboa in Lisbon, Portugal.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2022;19(7–9):48–54.

Abstract

The main objective of this preliminary review was to identify studies that investigated extreme forms of animal hoarding in an effort to define the concept of Noah syndrome, recently proposed as the animal variant of Diogenes syndrome. From the 52 scientific articles identified in our search, we included and analyzed 23 manuscripts. The main findings show that persons hoarding animals in squalor tend to be of advanced age and socially isolated, lacking perception of the consequences of their behavior on themselves, their families, and their animals. Neurological and psychiatric conditions, such as dementia, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), psychoses, and drug addiction were some of the most common underlying causes. We discuss psychopathological mechanisms, such as ageism and attachment disorders. Due to the limited number of manuscripts on this topic, more research is needed to develop effective intervention strategies, which should include not only psychiatric and neurologic care, but also veterinary care and familiarity with public health policies.

Keywords: Noah syndrome, animal hoarding, Diogenes syndrome, squalor

Noah syndrome has been recently described as a variant of Diogenes syndrome, presenting in persons with animal hoarding disorder.1 Though research is scarce, patients with this symptomology have presented to our daily practice over the last decade, especially in the psychiatry emergency room. In an effort to better conceptualize Noah syndrome, we performed a literature review, searching for common aspects of Diogenes syndrome and animal hoarding disorder. With the present article, we aimed to increase awareness among the neuropsychiatric community.

Diogenes Syndrome

Diogenes of Sinope was one of the founders of the Cynic philosophy, from the Greek Kynikos (meaning dog). He kept his need for clothing and food to a minimum, begged for a living, and lived in a large wooden barrel. Diogenes believed human beings lived artificially and hypocritically and followed ideas such as freedom from emotion, lack of shame, and contempt for social organization.2 In 1975, Clark et al3 described Diogenes syndrome in people with extreme self-neglect who hoard objects. It is associated with social isolation, rejection of external help, and no awareness of the abnormality of their behavior.3 Characterized by poor hygiene, it is also known as social breakdown syndrome,4 senile squalor syndrome,5 and self-neglect syndrome.6 Nevertheless, Diogenes would have not fulfilled criteria for this syndrome, as his motivation was a suspicious rejection of the world, rather than a desire to demonstrate self-sufficiency.7 Some authors believe the eponym should be dedicated to Plyushkin, a fictional character that obsessively collects everything he finds, portrayed in Nikolai Gogol’s novel Dead Souls (1842), instead.8 Others proposed to call it Havisham syndrome,9 after a woman from the Charles Dickens novel Great Expectations (1860).

Some researchers make a distinction between primary or pure Diogenes syndrome, when it is not associated with mental illness, and secondary or symptomatic Diogenes syndrome, when it is related to specific mental disorders or neurologic diseases. New onset in older age could be an example of secondary Diogenes syndrome, with most patients receiving a dementia diagnosis after several years of presentation.10 Although dementia is high on the list of differential diagnoses, there is a possibility that hoarding with squalor can be attributed to pre-existing personality traits.11 Some authors also questioned whether this behavior could be an indirect self-destructive, even suicidal, equivalent.12–14 In a systematic review dedicated to Diogenes syndrome, the described cases were typically referred to the healthcare system by neighbors due to being a hazard to themselves or others.15 Diogenes syndrome has no autonomy as a nosological entity, and therefore has not been included in the most recent versions of both the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) in 2013, and the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11), published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2018. Nevertheless, whenever encountering a patient with Diogenes syndrome, physicians should apply the ICD-11 code (6B24) and criteria for hoarding disorder, which entail the following:

- Hoarding disorder is characterized by an accumulation of possessions that results in living spaces becoming cluttered to the point that their use or safety is compromised.

- Accumulation occurs due to both repetitive urges or behaviors related to amassing items and difficulty discarding possessions due to a perceived need to save items and distress associated with discarding them. If living areas are uncluttered, this is only due to the intervention of third parties (e.g., family members), and amassment may be passive (e.g., accumulation of mail) or active (e.g., excessive acquisition of items).

- The symptoms result in significant distress or impairment in personal, family, social, educational, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.16

To make a diagnosis of hoarding disorder, according to the DSM-5, the following criterion must be met:

- Hoarding is not attributable to another medical condition (e.g., brain injury), and that hoarding is not better explained by the symptoms of another mental disorder (e.g., obsessive compulsive disorder [OCD]).17

Animal Hoarding

Animal hoarding reports have been recurrent in popular culture for centuries, as we can easily find references to characters, such as Noah in the book of Genesis in the Bible. According to the myth, Noah labored faithfully to build an ark at God’s command, embarking with his family and two animals of each species, ultimately saving humankind and all land animals from extinction during a great flood. Nevertheless, in the Jewish and Christian mythology, there is no reference to any kind of squalor in Noah’s ark, and therefore, the Noah syndrome eponym might be inaccurate. A more appropriate and contemporaneous example would be Eleanor Abernathy, the “crazy cat lady,” who, after experiencing burnout and psychological exhaustion, turned to alcohol and became obsessed with her cats in Matt Groening’s television series The Simpsons (1989).18

In 1981, more than thirty cases of multiple animal ownership were presented to the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA).19 Soon after, other individuals with similar behavior were characterized as animal collectors in publications for veterinarians and animal welfare professionals.20

In 1993, the first manuscript on hoarding disorder appeared in psychological literature.21 Hoarding, in medical literature, is defined as a pathological disorder, characterized by urges to acquire and store items due to assumed usefulness and emotional attachment. Difficulty in discarding current possessions and excessive household clutter associated with impaired functional psychological comorbidities are the hallmark of object hoarding and are required for this diagnosis.22,23 Hoarding disorder is associated with certain personality traits, including perfectionism, indecision, procrastination, and low-level self-control and problem solving.24,25 Individuals with hoarding disorder usually have low insight into the effects their hoarding behaviors have on themselves and others.26

In 1999, Patronek27 defined animal hoarding as a pathological human behavior that involves a compulsive need to obtain and control animals, coupled with a failure to provide minimal standards of care for animals and denial of the consequences of that failure. In the following year, the Hoarding of Animals Research Consortium (HARC) introduced animal hoarding as a term that was more consistent with existing medical, psychological, and psychiatric nomenclature, since the term “collecting” more appropriately described accumulations associated with benign hobbies.28

In 2002, the HARC defined animal hoarding using the following criteria:

- Accumulation of more than the usual number of companion animals

- Failure to provide animals with minimal standards of nutrition, sanitation, shelter, and veterinary care, with resulting illness or death

- Poor insight, with denial of the inability to provide adequate care and its impact on the animals, the household, and human occupants

- Persistence in collecting animals, despite failure providing them appropriate care.28

Since 2013, the DSM-5 specifically addressed animal hoarding using the HARC criteria, suggesting that it might be a special manifestation of the hoarding disorder. Prior to this, animal hoarding was not a distinct mental disorder, making it difficult for court systems to require psychiatric treatment in cases involving animal hoarders.29 In most cases of animal hoarding, the abnormal behavior goes unnoticed, since the image of elderly people feeding cats or dogs or taking them home is considered normal. Not uncommonly, it is considered as an altruistic gesture, is socially accepted, and is perceived as people seeking company and affection, mainly for patients who suffered stressful traumatic situations as grief and social abandonment.1 In cases analyzed in different studies, hoarding was a result of incessant animal collection and unstoppable reproduction, as well as the inability to donate animals.30 Frost et al31 noted that there is a difference between object and animal accumulation, as there is a strong affectional bond between the animal and patient, a link with living beings (not inanimate objects) that might contribute to the difficulty for hoarders to donate their animals. Compared with individuals who only hoard objects, individuals who hoard animals typically have poorer insight and live in less sanitary conditions, establishing a dynamic relationship that often entails a moralistically oriented rescue mission.32–34 Individuals who hoard animals typically fail to provide the animals with adequate food, water, sanitation, and veterinary care and are in denial about their inability to do so. They will ignore, minimize, or deny adverse events as obvious as starvation, severe illness, and death, along with environmental effects of the hoarding on their own health and the wellbeing of their family members. These patients hoard a large number of animals, neglecting their basic care and showing an inability to recognize the consequences this might have for the health and wellbeing of both the animals and the patients themselves. The high frequency of animal hoarding cases without object hoarding supports the recent assertion35 that animal hoarding represents a separate diagnostic group from object hoarding and suggests that this disorder deserves a new nosographic category based on new diagnostic criteria, entitled animal hoarding disorder.36

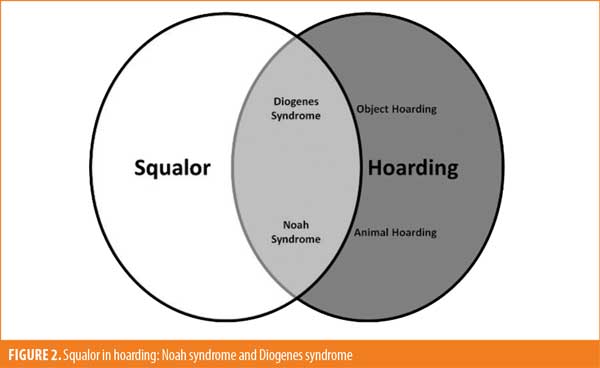

In Table 1, we compared the most important characteristics of hoarding disorder, Diogenes syndrome, and Noah syndrome. When summarizing this information, we realized the difficulty in separating these syndromic entities. For instance, should Noah syndrome be considered the animal hoarding version of Diogenes syndrome or animal hoarding disorder with squalor?

Methods

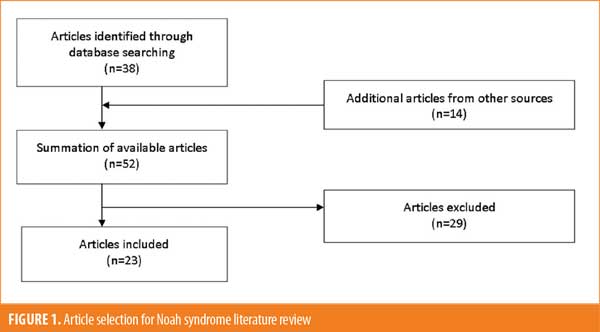

As the literature about Noah syndrome is not vast, any relevant articles were considered, regardless the date of publication, including single case reports and letters to the editor. The terms “Noah syndrome,” “Diogenes syndrome,” and “animal hoarding” were used to search PubMed in order to verify articles on the subject.

Inclusion criteria included articles related to Noah syndrome or animal hoarding written in English, Spanish, or Portuguese. Further additional articles were added through other sources, following a citation chain methodology, whenever it was deemed necessary. Figure 1 summarizes the article selection process.

Results

From the 52 scientific articles identified, we were included and analyzed 23 manuscripts.

The three subtypes of animal hoarding. Animal hoarding seems to be more complex than object hoarding in the forms it can take and the variety of underlying motivations. Therefore, three different animal hoarding subtypes have been proposed: the overwhelmed caregiver, the rescue hoarder, and the exploiter hoarder.37 The overwhelmed caregiver minimizes rather than denies animal care problems but cannot remedy these problems, despite the strong attachment to animals. The rescue hoarder feels a missionary zeal to save all animals, and actively seeks to acquire as many animals as possible because they oppose animal euthanasia and believe only they can provide adequate care. These patients represent significant challenges to mental health and law enforcement professionals, since their lack of insight typically renders them uncooperative. The exploiter hoarder is the most challenging type to manage in that they typically present with a personality disorder and are completely indifferent to the caused harm to the animals. They might be looking for financial gain from illegitimate soliciting funds. They can be charismatic, presenting an appearance that suggests a competent protective role to the public, media, officials, and courts. One well-known example is the case depicted in J.D. Thompson’s documentary, The Life Exotic: Or The Incredible True Story of Joe Schreibvogel (2016).

In theory, patients with any of these animal hoarding types are at risk of developing Noah syndrome, as soon as the individual fails to provide adequate care to the animals and starts living in squalor.

Attachment, age, and animal hoarding. Animal hoarding is associated with pathologically strong attachments to animals and accompanied by a history of difficulties with attachment to people. Individuals who hoard animals typically report feelings of insecurity related to chaotic or traumatic childhood, linked to experiences of parental separation, isolation, or frequent relocations, with animals being the only stable feature. The absence of nurturing relationships in childhood might cause a deep sense of loneliness in adulthood that these individuals struggle to fill. For these people, compulsive caregiving of animals might become the primary means of maintaining or building a sense of self.30 In 2017, Paloski30 proposed an explanatory model for animal hoarding that included early life stressors, plus difficulty in developing secure attachments in childhood and decision-making organizational skills. Some animal hoarders have experienced traumatic childhoods, leading to the inability to establish human relationships. The loss of an important adult relationship, a significant health crisis, or another traumatic triggering event can exacerbate animal hoarding. Negative family relationships early in life, unresolved grief due to untimely deaths or losses, emotional or physical abuse,38,39 and poorer attachment to parents might lead to a compensatory overattachment to animals. Frequently, persons who hoard animals describe their animals as children, and explain that their lives revolve around unconditional love of the animals.27 However, in 2009, Nathanson33 suggested that a primary feature of animal hoarding could be a question not about loving animals, but about animals providing a conflict-free relationship.

Animal hoarding tends to affect people with a low income who are middle-aged or older, often single, widowed, or divorced, socially isolated, and living alone in unhealthy conditions.34 These individuals typically show signs of self-neglect, which might be a result of illness related to ageism, that appear to be particularly relevant to the need to acquire animals, despite incapacities to maintain them.34 Losses that accompany aging, such as children moving away (empty nest syndrome), the deaths of spouses and friends, the disappearance of a reference group, or a dramatic drop in public status, can provide strong negative reinforcement of feelings of uselessness.40 Isolation contributes to diminished reality testing so much that self-neglecting individuals have decreased awareness of the risks involved in their behavior. There is a clear relationship between life-long experiences with negative social interactions and alienation later in life, which is related to the difficulty that individuals with self-neglect demonstrate once confronted by the critical perspectives of others.41 Independently of the psychological mechanism behind the animal hoarding behavior, we would apply Noah syndrome to these patients only when squalor is present.

Neuropsychiatric disorders and animal hoarding. Since the diagnosis of animal hoarding in the DSM-5 is mainly descriptive, rather than attempt to clarify the origins and nature of the problem, several approaches have been used to reconcile behaviors seen in animal hoarding with disorders such as OCD, delusional disorder, dementia, and addiction.29

One model attempts to compare animal hoarding to or consider it a symptom of OCD, since patients with animal hoarding disorder frequently perform unrealistic procedures to protect animals from harm, similar to the compulsive rituals practiced by patients with OCD.41 Prior to 2010, hoarding was typically considered a variant of OCD. However, additional research has suggested a more complex pattern of overlap with organic brain disease, depression, and personality disorders, leading to the designation of hoarding disorder as a distinct nosology.42,43

Some patients with animal hoarding behavior might suffer from a psychotic disorder, as some patients show recurrent beliefs about having a special ability to understand and empathize with animals. Most patients with animal hoarding disorder claim that the animals are well-cared for and healthy, despite evidence to the contrary, the HARC has suggested that it could be, in some cases, a highly specific form of delusional disorder, and that patients with animal hoarding disorder possess an unrealistic belief system.44

Some researchers have postulated that animal hoarding is an addiction disorder, as these individuals share many characteristics with patients with substance abuse disorders.45 Both types of patients are in denial over their problems, find excuses for their situation, might be socially isolated, claim to be persecuted, and neglect themselves and their surroundings. Therefore, animal hoarding behavior could be viewed as addictive behaviors, similar to compulsive shopping,44 gambling,46 or heavy smoking,47 in which impulse control is impaired.

Theoretically speaking, any severe neuropsychiatric condition could underlie an extreme form of animal hoarding aggravated by squalor, thus representing a case of Noah syndrome, either a functional, idiopathic, primary psychosis (e.g., OCD or schizophrenia) or an organic, symptomatic, secondary psychosis (e.g., dementia or drug abuse).

Discussion

Regardless of whether people who hoard animals also hoard objects, the inability to use living spaces because of disorganization and clutter appears to characterize both object and animal hoarding. Both are associated with neglect of the home environment, resulting in impairments in normal activities of daily living.26 However, clutter seems to be more a consequence of failure to discard trash and other items, particularly those associated with attempting to care for animals (e.g., food, cages, and bedding) than failure to maintain an organized household.28 More so than the number of animals, what defines the disorder is the inability of the individual to provide necessary care to the animals. Although both object and animal hoarding have similar characteristics, they appear to differ in the extent of sanitation problems. Squalor characterizes the homes of a minority of individuals who hoard objects48 but is a prominent feature of those who hoard animals.49 There is also a difference in the nature of items saved.50 In object hoarding, virtually everything imaginable is stored (e.g., paper, magazines, and clothes). In contrast, most people who hoard animals concentrate on only one species, most frequently dogs or cats.

Besides clutter and disorganization, an important criterion for hoarding disorder is difficulty in discarding.25 People who hoard animals seem to display similar difficulty in refusing to give up animals that are clearly sick, dying, or already dead. An intense distress accompanies attempts by authorities to remove animals.51 However, it is distinct from deliberate cruelty, where the perpetrator derives some form of pleasure from the neglect or abuse of an animal.44 Indeed, many people who hoard animals view their pets as members of their family and as possessing human-like qualities.21 In addition, they believe they have specific abilities to communicate with, understand, and/or provide care for animals.52

Typically, animal hoarding is associated with a lack of awareness, which makes any intervention difficult.53 In 2009, Patronek and Nathanson37 explained it is more effective to approach cases of animal hoarding with a broad perspective. Addressing the neuropsychiatric disorders that might be causing the behavior disturbance, as well as exploring issues with loss, grief, isolation, and attachment, might help mitigate animal hoarding behavior or at least facilitate intervention and treatment.

Of 71 cases reviewed by the HARC in 2002, 93 percent of the residential home interiors were unsanitary, while 70 percent presented fire hazards.28 Homes of animal hoarders not only often lack utilities, such as electricity or running water, but also accumulate infestations, animal carcasses, feces, urine, rotting food, and poor air quality, in addition to clutter that elevates the risk of fall injuries.54 Such living conditions hold major implications for public health, including risk for infectious diseases.55 If an individual who hoards animals lives with dependents, the neglect spreads to them as well. If there is an older person, child, or individual with incapacitation, the individual with animal hoarding will not be able to assist them. Moreover, animals seized from animal hoarding situations are typically found to be in poor health and in need of veterinary care.45,56,57

The American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) acknowledges that every veterinarian is likely to encounter animal hoarding in practice.58 However, it can be difficult to recognize, since signs can be subtle and easily misinterpreted as, unlike with deliberate abuse, overt intent to harm is absent, and some persons hoarding animals might masquerade under the guise of legitimate shelters, sanctuaries, hospices, or rescue groups. Veterinarians can play an extremely important role in detecting hoarding cases by recognizing animals that present signs of substantial suffering from long-term crowding, intensive confinement, and lack of exercise and socialization. Determining this poor quality of life could be particularly critical in cases in which the basics of food and water are minimally present and medical conditions are not dire, or when problems might be less severe for some animals than others.43 Veterinarians might be reluctant to report animal hoarding for a variety of reasons, including concerns about breaking confidentiality, unwillingness to become involved in legal proceedings, or fear of retaliation. However, once a case of animal hoarding is identified, the veterinarian can work to gain the person’s trust to better understand the situation and consult with appropriate community agencies. Some researchers support the development of an interdisciplinary approach to addressing animal hoarding, building on a community-wide interdisciplinary task force with the mandate and ability to address suspected cases of animal hoarding.45 A collaborative model approach has also been used in some communities where task forces were implemented, including targeted law enforcement training, mental health services to address human psychological components, crisis counseling services, and meetings to inform local attorneys about animal hoarding prior to appearing in court.54

Among people who hoard objects, most report a chronic course, with a significant minority describing a worsening one. The course in animal hoarding seems to be chronic as well, with a tendency to worsen overtime and high recidivism after the removal of animals.5 Mental health agencies, social services, and public authorities are often unable or unwilling to assist in animal hoarding cases because the behavior is excused as a lifestyle choice and, therefore, is not considered a public health issue. Similarly, there are some people who hoard and live in squalor for survival and might not have a mental disorder.

Despite the efforts of healthcare systems, animal protection organizations, and primary and secondary support networks, treatment results are often disappointing. Studies indicate that patients return to hoarding at the first opportunity they have.46 The high risk of recidivism is likely associated with low levels of insight. Little research exists on the treatment of this disorder. Nevertheless, it is recognized that building a trusting relationship, reducing social isolation, and putting more focus on issues with grief, loss, and attachment might help mitigate animal hoarding and facilitate intervention.43 Typically, these patients do not follow their treatment plans, even after moving to a larger house with better conditions.59

In order to prevent patients with animal hoarding from relapsing, it is important they receive the necessary care, counseling, or treatment for underlying medical and/or psychiatric conditions. Patients often resume hoarding at the earliest opportunity, and some refuse to receive treatment or decide to move away to start hoarding again.30

To have a consistent strategy that provides better results, community interventions based on collaborative and solution-focused approaches should be considered. In addition, there is a strong need for research on animal hoarding and successful intervention strategies.60 More work is required to change the public perception of animal hoarding and deal with these cases using a collaborative approach that involves family, neighbors, and medical and social institutions and provides increased support to the patient, family, and animals.

Conclusion

Noah syndrome might be an extreme form of animal hoarding disorder, as Diogenes syndrome might be an extreme form of hoarding disorder. As both syndromes include squalor, we acknowledge that some authors will conceptualize Noah syndrome as the animal variant of Diogenes syndrome. We believe that whenever the squalor is present in an animal hoarding situation, it might be useful to describe it as a case of Noah syndrome (Figure 2).

The development of a community-wide interdisciplinary approach involving psychiatric, veterinary, social, and public health services that can address suspected cases of animal hoarding might benefit many people and animals and alleviate considerable suffering, community expense, and legal complications associated with this disorder. Further studies are necessary to better elucidate the characteristics of this underrecognized public health and welfare problem.

References

- Saldarriaga-Cantillo A, Rivas Nieto JC. Noah syndrome: a variant of Diogenes syndrome accompanied by animal hoarding practices. J Elder Abus Negl. 2015;27(3):270–275.

- Cipriani G, Lucetti C, Vedovello M, Nuti A. Diogenes syndrome in patients suffering from dementia. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2012;14(4):455–460.

- Clark AN, Mankikar GD, Gray I. Diogenes syndrome. A clinical study of gross neglect in old age. Lancet. 1975;1(7903):366–368.

- Macmillan D, Shaw P. Senile breakdown in standards of personal and environmental cleanliness. Br Med J. 1966;2(5521):227–229.

- Shah AK. Senile squalour syndrome: what to expect and how to treat it. Geriatr Med. 1990;26:29–34.

- Reifler BV. Diogenes syndrome: of omelettes and souffles. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(12):1484–1485.

- Marcos M, Gomez-Pellin MDC. A tale of a misnamed eponym: Diogenes syndrome. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23(9):990–991.

- Cybulska E. Senile squalor: Plyushkin’s not Diogenes’ syndrome. Psychiatr Bull. 1998;22:319–320.

- Byard RW. Diogenes or Havisham syndrome and the mortuary. Forensic Sci Med Pathol. 2014;10(1):1–2.

- Thibault J. Analysis and treatment of self-neglectful behaviors in three elderly female patients. J Elder Abus Negl. 2007;19(3–4):151–166.

- Salmon E, Degueldre C, Franco G, Franck G. Frontal lobe dementia presenting as personality disorder. Acta Neurol Belg. 1996;96(2):130–134.

- Byard RW, Tsokos M. Forensic issues in cases of Diogenes syndrome. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2007;28(2):177–181.

- McIntosh J, Hubbard R. Indirect self-destructive behavior among the elderly: a review with case examples. Gerontol Soc Work. 1999;13(1–2):37–46.

- Thibault JM, O’Brien JG, Turner LC. Indirect life-threatening behavior in elderly patients. J Elder Negl. 1999;11(2):21–32.

- Almeida R, Ribeiro O. Síndrome de Diógenes: revisão sistemática da literatura. Rev Port Saú Púb. 2012;30(1):89–99.

- World Health Organization. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 11th edition. World Health Organization; 2018.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Tyler A. The Simpsons: the crazy cat lady’s dark and tragic backstory explained. Screen Rant. 3 Oct 2020. https://screenrant.com/simpsons-show-crazy-cat-lady-eleanor-abernathy-backstory-explained/. Accessed 18 Jul 2022.

- Worth C, Beck A. Multiple ownership of animals in New York City. Trans Stud Coll Physicians Phila. 1981;3(4):280–300.

- Lockwood R, Cassidy B. Killing with kindness? Hum Soc News. 1988;1–5.

- Frost RO, Gross RC. The hoarding of possessions. Behav Res Ther. 1993; 31(4): 367–381.

- Berry C, Patronek GJ, Lockwood R. Long-term outcomes in animal hoarding cases. Anim Law. 2005;11:167–193.

- Snowdon J, Halliday G. A study of severe domestic squalor: 173 cases referred to an old age psychiatric service. Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(2):308–314.

- Timpano KR, Schmidt NB. The relationship between self-control deficits and hoarding: a multimethod investigation across three samples. J Abnorm Psychol. 2013;122(1):13–25.

- Woody SR, Kellman-McFarlane K, Welsted A. Review of cognitive performance in hoarding disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 2014;34(4):324–336.

- Tolin DF, Fitch KE, Frost RO, Steketee G. Family informant’s perception of insight in compulsive hoarding. Cogn Ther Res. 2010;34(1):69–81.

- Patronek GJ. Hoarding of animals: an under-recognized public health problem in a difficult-to-study population. Public Heal Rep. 1999;114(1):81–87.

- Hoarding of Animals Research Consortium. Health implications of animal hoarding. Heal Soc Work. 2002;27(2):126–136.

- Lockwood R. Animal hoarding: the challenge for mental health, law enforcement, and animal welfare professionals. Behav Sci Law. 2018;36(6):698–716.

- Paloski LH, Ferreira EA, Costa DB, et al. Animal hoarding disorder a systematic review. Psico (Porto Alegre). 2017;48:243–249.

- Frost RO, Patronek G, Rosenfield E. Comparison of object and animal hoarding. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(10):885–891.

- Frost R. People who hoard animals. Psychiatric Times. 2000;17(4).

- Nathanson JN. Animal hoarding: slipping into the darkness of comorbid animal and self-neglect. J Elder Abus Negl. 2009;21(4):307–324.

- Steketere G, Gibson A, Frost RO, et al. Characteristics and antecedents of people who hoard animals: an explanatory comparative interview study. Rev Gen Psychol. 2011;15(2):114–124.

- Ferreira EA, Paloski LH, Costa DB, et al. Animal hoarding disorder: a new psychopathology? Psychiatry Res. 2017;258:221–225.

- Dozier ME, Bratiotis C, Broadnax D, et al. A description of 17 animal hoarding case files from animal control and a humane society. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:365–368.

- Patronek GJ, Nathanson JN. A theoretical perspective to inform assessment and treatment strategies for animal hoarders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(3):274–281.

- Cassidy J, Mohr JJ. Unsolvable fear, trauma, and psychopathology: theory, research, and clinical considerations related to disorganized attachment across the life span. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2011;8(3):275–298.

- Lyons-Ruth K, Dutra L, Schuder MR, Bianchi I. From infant attachment disorganization to adult dissociation: relational adaptations or traumatic experiences? Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2006;29(1):63–86.

- Rathbone-McCuan E. Self-neglect in the elderly: knowing when and how to intervene. Aging Magazine. 1996; 367:44–49.

- Bozinovski SD. Older self-neglecters: Interpersonal problems and the maintenance of self-continuity. J Elder Abuse Negl. 2000;12(1):37–56.

- Tolin DF, Villavicencio A, Umbach A, Kurtz MM. Neuropsychological functioning in hoarding disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2011;189(3):413–418.

- Campos-Lima AL, Torres AR, Yucel M, et al. Hoarding pet animals in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2015;27(1):8–13.

- Frost RO. Hoarding, compulsive buying and reasons for saving. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36(7–8):657–664.

- Lockwood R. The psychology of animal collectors. Trends. 1994;9:18–21.

- Frost RO, Meagher BM, Riskind JH. Obsessive-compulsive features in pathological lottery and scratch-ticket gamblers. J Gambl Stud. 2001;17(1):5–19.

- Raines AM, Unruh AS, Zvolensky MJ, Schmidt NB. An initial investigation of the relationships between hoarding and smoking. Psychiatry Res. 2014;215(3):668–674.

- Rasmussen JL, Steketee G, Frost RO, et al. Assessing squalor in hoarding: the Home Environment Index. Community Ment Heal J. 2014;50(5):591–596.

- Poythress EL, Burnett J, Naik AD, et al. Severe self-neglect: an epidemiological and historical perspective. J Elder Abus Negl. 2006;18(4):5–12.

- Mataix-Cols D, Frost RO, Pertusa A, et al. Hoarding disorder: a new diagnosis for DSM-V? Depress Anxiety. 2010;27(6):556–572.

- Arluke A, Frost R, Steketee G, et al. Press reports of animal hoarding. Soc Anim. 2002;10(2):113–135.

- Calvo P, Duarte C, Bowen J, et al. Characteristics of 24 cases of animal hoarding in Spain. Anim Welf. 2014;23(2):199–208.

- Fond G, Jollant F, Abbar M. The need to consider mood disorders, and especially chronic mania, in cases of Diogenes syndrome (squalor syndrome). Int Psychogeriatr. 2011;23(3):505–507.

- Fleury G, Gaudette L, Moran P. Compulsive hoarding: overview and implications for community health nurses. J Community Heal Nurs. 2012;29(3):154–162.

- Brooks JW, Roberts EL, Kocher K, et al. Fatal pneumonia caused by extrintestinal pathogenic Eschiria Coli (ExPEC) in a juvenile cat recovered from an animal hoarding incident. Vet Microbiol. 2013;167:704–707.

- Storch EA, Rahman O, Park JM, et al. Compulsive hoarding in children. J Clin Psychol. 2011;67(5):507–516.

- Strong S, Federico J, Banks R, Williams C. A collaborative model for managing animal hoarding cases. J Appl Anim Welf Sci. 2019;22(3):267–278.

- Kuehn BM. Animal hoarding: a public health problem veterinarians can take a lead role in solving. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2002;221(8):1087–1089.

- Swanberg I, Arluke A. The Swedish swan lady. Soc Anim. 2016;24(1):63–67.

- Guerra S, Sousa L, Ribeiro O. Report practices in the field of animal hoarding: a scoping study of the literature. J Ment Health. 2021;30(5):646–659.