Funding/financial disclosures. The authors have no conflict of interest relevant to the content of this letter. No funding was received for the preparation of this letter.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2022;19(4–6):9–10.

Dear Editor:

In recent decades, the prevalence of neurodevelopmental disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and autism spectrum disorder (ASD), has been increasing.1 Patients with autism suffer from many oral health problems. Various studies have consistently indicated that they are at higher risk for dental caries, periodontal disease, and altered oral flora.2 In addition, malocclusions are frequently observed in these patients and could be an indication for orthognathic surgery.3 However, during orthodontic treatment, unpredictable behavior, hyperactivity, and short attention span can be difficult to manage.4 How to make decisions about orthognathic surgery is a major clinical challenge.

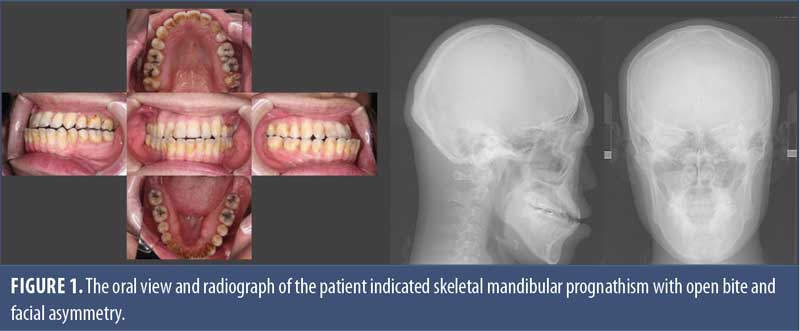

A 42-year-old male patient with autism came to our psychosomatic dentistry department with a request to consider the possibility of orthognathic surgery for malocclusion. The patient had an anterior crossbite and an open bite, but the posterior bite allowed for food intake (an Angle class III; Figure 1). He was diagnosed by an orthodontist as having skeletal mandibular prognathism with open bite and facial asymmetry, and orthognathic surgery was recommended. In patients with autism, facial deformities not only cause functional problems, but also frequently exposes the patient to associated stigma. Orthognathic surgery has the potential to solve both of these problems. However, the patient has been under psychiatric care for more than 10 years, with a diagnosis of autism and a comorbidity, somatic symptom disorder. The most recent medications prescribed to the patient were aripiprazole 6mg/day, amitriptyline 50mg/day, duloxetine 60mg/day, trazodone 50mg/day, brotizolam 0.5mg/day, and levocetirizine 5mg/day, but no cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) program was in place.

A team of orthodontists, psychiatrists, and internists, led by a psychosomatic dentist, discussed the advantages and disadvantages of orthognathic surgery and whether the patient could tolerate it. The patient had a history of severe anxiety and a tendency to have physical reactions to various environmental changes, putting him at risk for worsening psychiatric symptoms in the perioperative period. Orthodontic treatment for patients with autism is difficult to manage perioperatively due to difficult home care.5 Next, we considered the impact of the psychotropic medication the patient was taking on the surgery. Psychotropic medications have the advantage of controlling psychiatric symptoms and allowing orthodontic treatment. On the other hand, psychotropic drugs can affect the teeth and delay recovery after orthognathic surgery. For example, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are associated with deleterious effect on bone remodeling, which is necessary for tooth movements.6 Lithium carbonate inhibits tooth movements in animal models.7 Diazepam increases the rate of tooth movement,8 and anticonvulsants can induce the orthodontic tooth movement by decreasing the bone density.9 Although psychotropic drugs have little direct effect on the bone, we could not deny the possibility that they could affect the postoperative course.

After considering these factors, the treatment team suggested the patient not undergo surgery for the following three reasons. First, the posterior occlusion was functional enough for food intake. Second, psychotropic medications that might affect the teeth cannot be suddenly discontinued, which might cause unpredictable problems with bone formation. Third, the patient would have difficulty adapting to the new occlusion after surgery. The decision of the treatment team was communicated to the patient by the psychosomatic dentist, and eventually, the patient himself decided to follow the process without surgery.

Even when oral findings indicate that orthognathic surgery is needed, patient cooperation and understanding are essential. Specifically, psychosomatic dentists with knowledge of dentistry and an understanding of the patient’s mental state, with input from the orthodontist, initiated CBT in an ongoing attempt to enable postoperative management, but this has not yet resulted in surgery. At the same time, the team consulted with a psychiatrist and decided to begin discontinuing or reducing psychotropic medications and to continue to explore the possibility of future surgery.

Orthognathic surgery usually imposes a high level of anxiety in patients.10 Indications for orthognathic surgery need to be discussed by a multidisciplinary team and ultimately decided together with the patient, taking into account not only local issues, such as facial features and teeth alignment, but also the ability to follow instructions during the perioperative period, as well as stigma and psychological issues.

References

- Antshel KM, Russo N. Autism spectrum disorders and ADHD: overlapping phenomenology, diagnostic issues, and treatment considerations. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21(5):34.

- Ferrazzano GF, Salerno C, Bravaccio C, et al. Autism spectrum disorders and oral health status: review of the literature. Eur J Paediatr Dent. 2020;21(1):9–12.

- Vellappally S, Gardens SJ, Al Kheraif AA, et al. The prevalence of malocclusion and its association with dental caries among 12–18-year-old disabled adolescents. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:123.

- Suga T, Tu TTH, Takenoshita M, et al. Psychosocial indication for orthognathic surgery in patients with psychiatric comorbidities. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2020;74(11):621–623.

- Neeley WW 2nd, Kluemper GT, Hays LR. Psychiatry in orthodontics. Part 1: typical adolescent psychiatric disorders and their relevance to orthodontic practice. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129(2):176–184.

- Chandra P, Roy S, Kumari A, et al. Role of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors in prognosis dental implants: a retrospective study. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2021;13(Suppl 1):S92–S96.

- da Silva Kagy V, Trevisan Bittencourt Muniz L, Michels AC, et al. Effect of the chronic use of lithium carbonate on induced tooth movement in Wistar rats. PLoS One. 2016;11(8):e0160400.

- Burrow SJ, Sammon PJ, Tuncay OC. Effects of diazepam on orthodontic tooth movement and alveolar bone cAMP levels in cats. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 1986;90(2):102–105.

- Akhoundi MSA, Sheikhzadeh S, Mirhashemi A, et al. Decreased bone density induced by antiepileptic drugs can cause accelerated orthodontic tooth movement in male Wistar rats. Int Orthod. 2018;16(1):73–81.

- Thompson DG, Tielsch-Goddard A. Improving management of patients with autism spectrum disorder having scheduled surgery: optimizing practice. J Pediatr Health Care. 2014;28(5):394–403.

With regards,

Takayuki Suga, DDS, PhD; Takahiko Nagamine MD, PhD; Trang T.H. Tu, DDS, PhD; Keiji Moriyama, DDS, PhD; and Akira Toyofuku, DDS, PhD

Drs. Suga, Nagamine, Tu, and Toyofuko are with the Department of Psychosomatic Dentistry, Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Tokyo Medical and Dental University in Tokyo, Japan. Dr. Nagamine is with the Department of Psychiatric Internal Medicine, Sunlight Brain Research Center in Hofu, Japan. Dr. Tu is with the Department of Basic Dental Science, Faculty of Odonto-Stomatology, Ho Chi Minh Medicine and Pharmacy University in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam. Dr. Moriyama is with the Department of Maxillofacial Orthognathics, Graduate School of Tokyo Medical and Dental University in Tokyo, Japan.

Ethics approval and consent to participate. The ethics committee of the Faculty of Dentistry Tokyo Medical and Dental University approved this study (D2013-005), and written informed consent was obtained from the patient for this study.