by Takashi Ohnishi, MD, PhD; Hisanori Kobayashi, PhD; Toshio Yamaoka; Tokiko Toma; Keiko Imai; Akihide Wakamatsu; and Kenichi Noguchi, PhD

by Takashi Ohnishi, MD, PhD; Hisanori Kobayashi, PhD; Toshio Yamaoka; Tokiko Toma; Keiko Imai; Akihide Wakamatsu; and Kenichi Noguchi, PhD

Drs. Ohnishi, Kobayashi, and Noguchi and Mr. Wakamatsu are with the Medical Affairs Division of Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K. in Tokyo, Japan. Mr. Yamaoka, Ms. Toma, and Ms. Imai are with the Drug Safety Surveillance Department, Japan Safety & Surveillance Division of Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K. in Tokyo, Japan.

FUNDING: Support for this study was provided by Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K.

DISCLOSURES: All authors are full-time employees of Janssen Pharmaceutical K.K., which is a division of Johnson & Johnson Japan.

ABSTRACT: Objective. We sought to evaluate the effects of a one-month paliperidone palmitate formulation (PP1M) on employment status, social function, symptomatology, and safety and conducted a two-year postmarketing surveillance study of Paliperidone Palmitate 1 Month (PP1M).

Methods. Patients diagnosed with schizophrenia participated in the study. Employment status was recorded at baseline and changes were measured at one and two years. Social functioning and symptomatology were assessed using the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) and the Clinical Global Impression—Schizophrenia (CGI–SCH). Data on adverse events were also collected.

Results. A total of 1,319 patients were enrolled in this investigation, including 1,306 who were evaluable for safety and 1,279 who were evaluable for efficacy. The maintenance rate during the observation period was 49.4 percent. During the observation period, the percentages of patients reporting employment significantly increased: 24.3 percent of patients were employed in some capacity at baseline, 32.5 percent of patients were employed at one year, and 34.6 percent of patients were employed at two years. Significant improvements were observed in both SOFAS and CGI–SCH scores during the observation period. The percentage of patients with socially functional remission also significantly increased. A strong association between the improvement of social function, gender, and monotherapy versus polypharmacy and the improvement of employment status was observed. A total of 29.3 percent of patients experienced at least one adverse event. There were no unexpected findings from long-term treatment and a safety profile, including mortality.

Conclusion. PP1M treatment appears to improve not only schizophrenic symptoms but also functional outcomes.

KEYWORDS: Schizophrenia, social function, employment

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2020;17(40–44)

Schizophrenia is a chronic disabling disease with long-term consequences for patients. It generally onsets from adolescent to early adulthood and often requires recurrent hospitalizations, resulting in poor social functioning and long-term community support. Current pharmacological treatment in schizophrenia has focused on the reduction of symptomatology and the prevention of relapse. However, the aims of antipsychotic treatment have moved beyond just controlling symptoms and preventing relapse to include the achievement and maintenance of remission.1 The goal of treatment for patients with schizophrenia should involve restoring them to full function, including competitive employment. Indeed, most people with psychiatric disorders have a desire to work but are more likely to experience adverse labor market outcomes than people without psychiatric disorders.2 Employment is known to increase self-esteem, foster a sense of belonging and physical well-being, and provide a normative context that helps people develop a sense of control over their lives.3,4 However, several studies have indicated that employment rates for people with schizophrenia are much lower than in the general population, ranging from 14.5 to 17.2 percent in the United States,5,6 11.5 percent in France, 12.9 percent in the United Kingdom, and 30.3 percent in Germany.7 In Japan, the employment rate in patients with severe mental disorders is around five percent, suggesting that about 95 percent of patients with schizophrenia are unemployed.8 These results indicate that patients with schizophrenia do not enjoy the multiple benefits of paid employment. Thus, schizophrenia also has a considerable economic burden on patients’ families and society. Indeed, the unemployment cost for schizophrenia in Japan was estimated at about JPY 1.85 trillion (USD 15.8 billion).8 In this context, employment status should be one of critical domains in the real-world outcomes of patients with schizophrenia.

Several interventions, such as assertive community treatment, supported employment, medication management, illness management and recovery, and family psychoeducation have been used to help patients with severe mental disorders gain full employment.9 A recent meta-analysis concluded that supported employment and augmented supported employment were the most effective interventions for people with severe mental disorders in terms of obtaining and maintaining employment without increasing the risk of adverse events.10 Pharmacological therapy contributes to a reduction in psychotic symptoms; however, it has been considered to have little impact on the improvement of social, cognitive, and emotional aspects of schizophrenia that are related employment status. Therefore, nonpharmacological therapy, such as assertive community treatment and psychosocial rehabilitation combined with pharmacotherapy, have been used to improve employment status in schizophrenia.2,11

As mentioned above, antipsychotics would not have direct effects on social skills and cognitive function intimately associated with employment in patients with schizophrenia. But, it could be possible that antipsychotics improve and maintain employment status via symptomatic control and relapse prevention. Long-acting injectables (LAIs) have been developed to combine benefits of second-generation antipsychotic agents with the adherence advantage of long-acting formulations. Paliperidone Palmitate 1 Month (PP1M) is a second-generation LAI. Several studies have demonstrated efficacy, effects on relapse prevention, and functional improvement of PP1M treatment.12,13 Despite evidence of improvement of functionality with PP1M treatment, there are few data reporting on its influence on employment status.13 One previous study demonstrated that PP1M treatment was associated with prompt and sustained improvements in functioning and employment status in patients with schizophrenia.13 Another study reporting the influence on employment status of risperidone long-acting injectable treatment also demonstrated improvement of employment status.14

Since employment status is a critical domain in real-world outcomes in patients with severe mental disorders, the investigation of the influence of treatment on employment status should be conducted under routine clinical (real-world) settings. We conducted a two-year postmarketing surveillance study of PP1M to evaluate the influence on employment status, social function, symptomatology, and safety under routine clinical settings.

The aims of the present surveillance were: 1) to clarify the influence of long-term PP1M treatment under routine clinical settings on employment status in patients with schizophrenia; 2) to demonstrate improvements in social function as evaluated by the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS),15 functional remission rate, symptomatology as evaluated by the Clinical Global Impression—Schizophrenia (CGI-SCH),16 and time to discontinuation during two years of treatment with PP1M; 3) to clarify the relationship between the improvement of employment status and improvement of symptomatology, social function, and demographic variables, such as sex and age; and 4) to assess the safety of PP1M under routine clinical practice.

Methods

Study design. This was a multicenter 12-month study on use of PP1M newly initiated as an antipsychotic treatment with an additional 12-month extension period. Patients having an established diagnosis of schizophrenia who had recently been switched to or started on PP1M were the target of this surveillance. There were no exclusion criteria; however, patients without a history of paliperidone or risperidone treatment were strongly recommended prior use of paliperidone or risperidone to test allergic reactions. Physicians were advised that all treatments and dose adjustments should be based on approved local labels and that management decisions should be made at the physician’s discretion, using clinical judgment and routine practice. No study drug was provided: patients received medication according to their usual care.

The protocol of this surveillance was assessed by an internal review board of Janssen Pharmaceutical (Research Concept Review Board of Janssen Pharmaceutical), including ethical aspects, and was also approved by the Pharmaceuticals and Medical Devices Agency (PMDA). Performing this postmarketing surveillance study was part of the mandatory requirements determined and reviewed by the PMDA. The surveillance was conducted in accordance with the relevant Japanese regulations for Good Postmarketing Study Practice (Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare Ministerial Ordinance no. 171). Each site (hospital or clinic) followed its own regulations or standards for obtaining institutional review board approval, including regarding informed consent from the participants, as is usual for postmarketing surveillance research in Japan. This surveillance was registered with the UMIN Clinical Trials Registry (registration number. UMIN000018665).

Assessments. At each postbaseline visit (3 months, 12 months, and 24 months), respondents were assessed. Date of employment status change was elicited and the category of employment was recorded from the fixed choices following nine categories based on patient responses: full-time employment (FT), part-time employment (PT), casual employment (C), sheltered work (SW), unemployed but seeking work (US), unemployed and not seeking work (UNS), retired (R), not employed outside the home (NEOH), and student (S). In this surveillance, we defined that categories of FT, PT, C, and SW as employed. Employment rates were calculated by following two methods: 1) numbers of FT+PT+C+SW/numbers of all nine categories or 2) numbers of FT+PT+C+SW/ numbers of FT+PT+C+SW+US. According to the United States Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), retirees, people who are unemployed but not seeking work, students, and people who are not employed outside of the home are excluded from the labor pool (assuming that these people are not part of the potential working population)17; therefore, the denominator of the second method of calculation for employment indicates the labor pool of this survey.

Social function was assessed with SOFAS, developed by the American Psychiatric Association for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition to operationalize functioning, which improves on the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale by incorporating the impact of psychological and general medical symptoms on patient functioning.15 The SOFAS was scored on a scale of zero to 100 points as a 10-point scale from one to 10 points (1=persistent hygiene problems) to 91 to 100 points (“10”=“superior functioning”) for the current period at baseline, three months, six months, 12 months, and 24 months. Social functional remission was defined as follows: SOFAS score of 61 points or more was maintained for more than six months. Regarding the remission rate at the baseline, eligible patients had a SOFAS score of 61 points or more regardless of their maintained periods.

Symptom severity was assessed with the CGI-SCH at baseline, one month, three months, six months, and 12 months. CGI-SCH was scored on a seven-point scale from 1=“normal” to 7=“among the most extremely ill” for each symptom domain (overall, positive, negative, depressive, cognitive).16 Because this was a one-year surveillance study plus an additional one-year extension design for evaluating the long-term treatment effects of PP1M on social function and employment status, symptom severity was assessed only during the first one-year period.

In addition to the items above, all adverse events (AEs) were also collected. Electronic data capture was used, and most of the data were transcribed by physicians from the source documents on the electronic case report form and then transmitted in a secure manner to the sponsor.

Statistical analyses. Since more than 40 percent of patients were given other antipsychotics combined with PP1M (polypharmacy), it could be possible that observed results are related to the effects of other antipsychotics rather than that of PP1M treatment. Therefore, we performed post-hoc analyses for evaluating differences between monotherapy and polypharmacy groups. Since registration trials of PP1M were conducted with initial loading regime,18 we also performed additional analyses for social function and employment status in the subgroup of patients who received the initial loading regime.

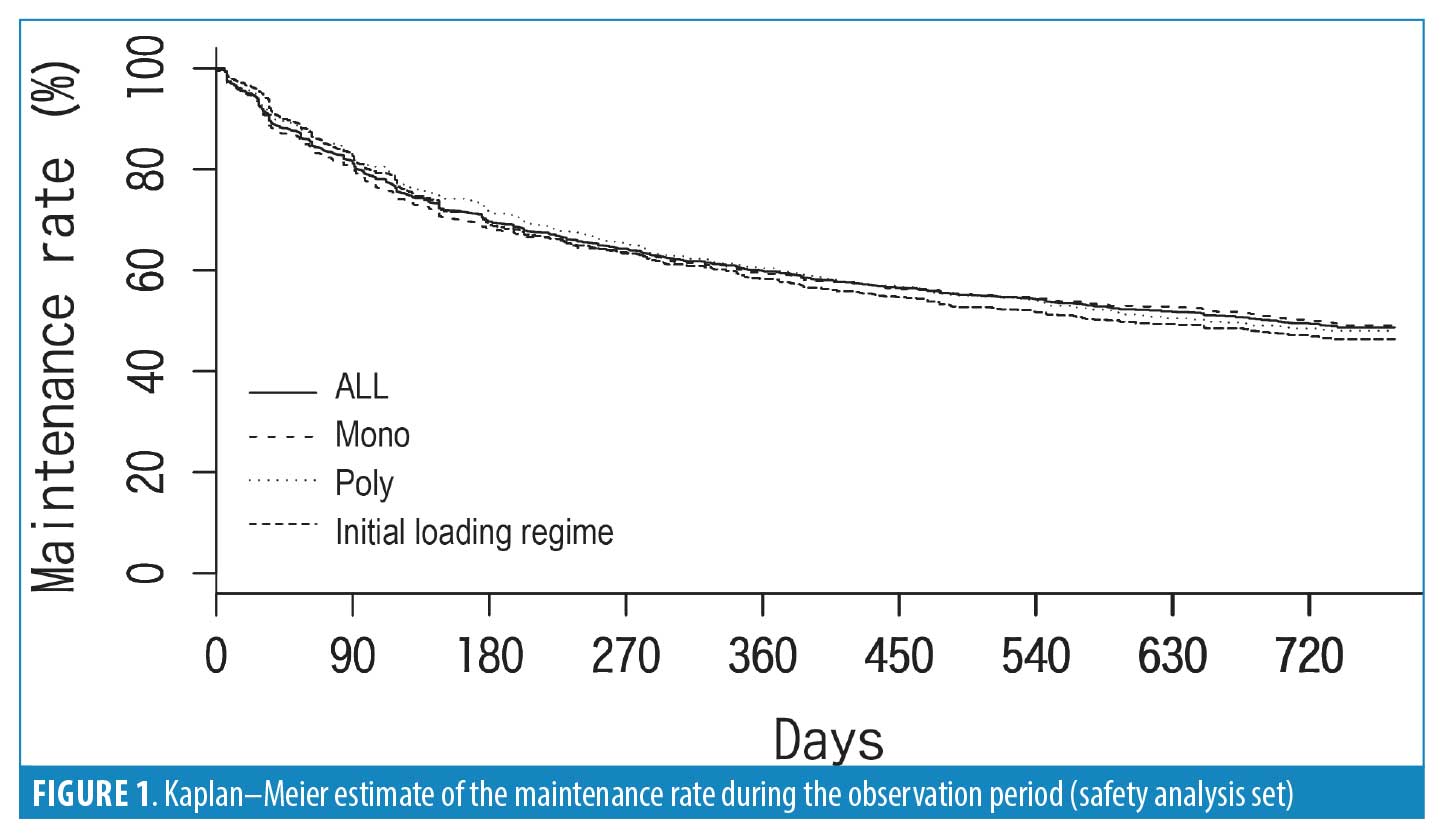

The discontinuation rate was calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and the monotherapy versus polypharmacy comparison in terms of discontinuation rate was made using the log-rank test.

The categories of employment at baseline and each visit were summarized using frequencies and percentages. Changes within categories from baseline to each visit were tested using the pairwise Fisher’s test (Holm’s method). Time effects on SOFAS and CGI-SCH scores were analyzed by generalized linear mixed models (GLMM). Time, age, sex, SOFAS, and CGI-SCH scores at the baseline and the interaction of time × monotherapy versus polypharmacy were modeled. Patient identification numbers were also included in the model as random variables. The last-observation-carried-forward (LOCF) approach was used to handle missing data. Post-hoc comparisons for each time point against baseline were also examined using Dunnett’s test. The proportion of function remission (defined as achieving a SOFAS score of 61 points or more for two consecutive six-month periods) was also reported at each time point. The patients who have achieved SOFAS scores of 70 points or more at baseline were treated as achieving functional remission at baseline.

To identify variables that explained improved employment status, logistic regression analysis was performed. The factors associated with improved employment status were regressed by changes (one month minus baseline) in CGI-SCH and SOFAS (last observation minus baseline) scores and patient’s demographic characteristics, such as sex, age, and monotherapy versus polypharmacy. We used changes during the first month of CGI-SCH scores as a variable for early symptoms because previous studies have suggested that early improvement of schizophrenic symptoms is associated with later functional remission.24 This is also an effective means to avoid inherent multicollinearity amongst time changes of CGI-SCH scores. We defined two categories of changes of employment status as follows: 1) improvement of employment status or maintenance of competitively employed status (part-time or full-time employment at baseline and 2 years), or 2) worsening or no change of employment status for two years. For this analysis, we used observed cases and excluded subjects who were categorized as retired.

Statistical analyses were conducted using R version 3.5.0 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Two-sided p-values of less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

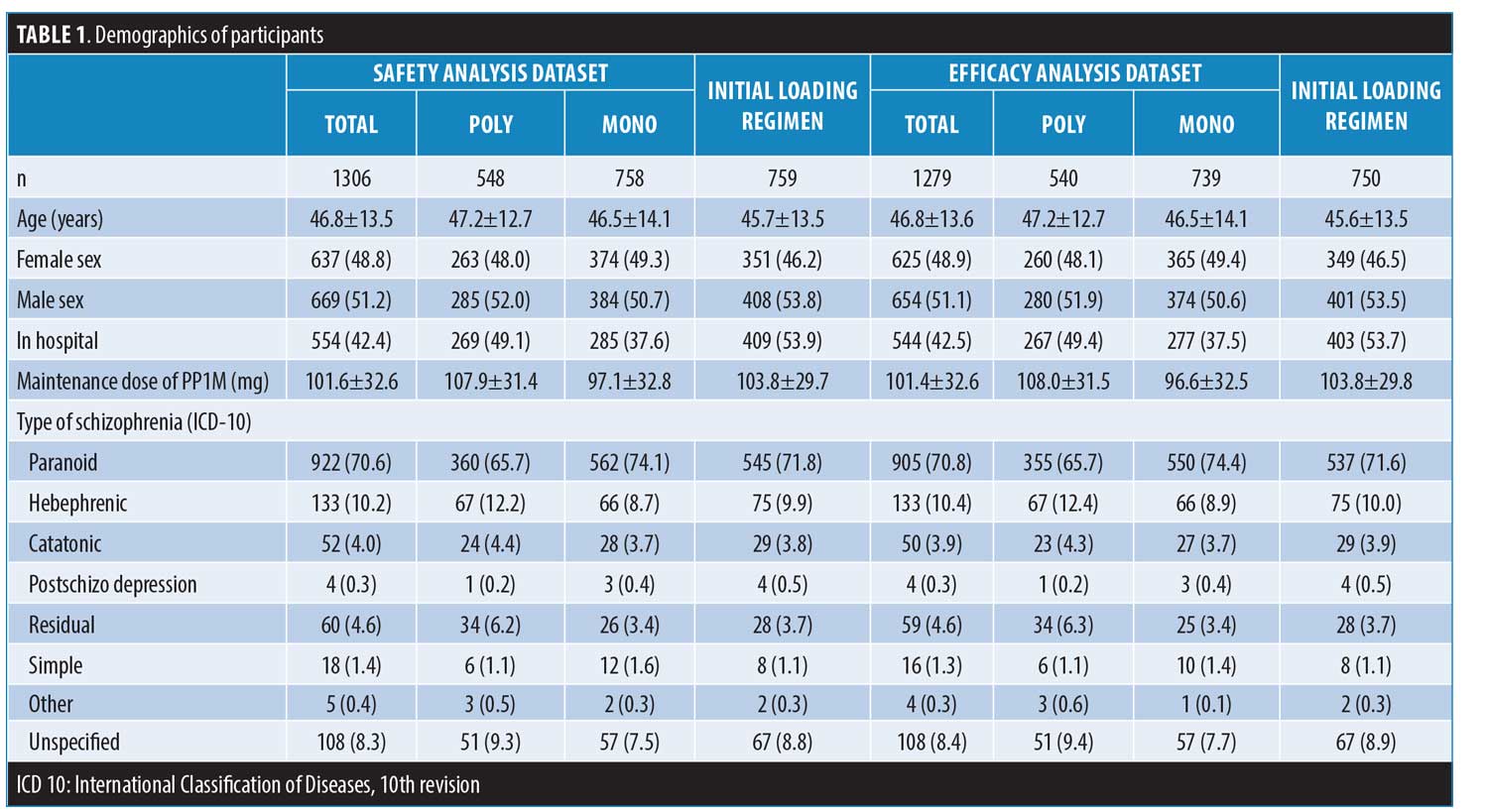

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics. A total of 1,319 patients were enrolled in the surveillance study, including 1,306 who were evaluable for safety and 1,279 who were evaluable for efficacy. Patient characteristics of each analytical group are summarized in Table 1. Baseline characteristics appeared similar in both analytical groups. The mean ± standard deviation (SD) age was 46.8±13.5 years, and 48.8 percent of patients were female. Meanwhile, 42.4 percent of patients were hospitalized at surveillance entry. The mean ± SD maintenance dose of PP1M was 101.6±32.6mg and 42 percent of patients in the safety analysis set were given other antipsychotics [except risperidone: n=74 and paliperidone extended-release (PAL-ER): n=33] combined with PP1M (polypharmacy). Other provided antipsychotics included olanzapine (n =192), quetiapine (n=118), aripiprazole (n=95), blonanserin (n=64), perospirone (n=7), and typical antipsychotics (n=278).

The subgroup of the initial loading regime consisted of 759 patients for safety analysis and 750 patients for efficacy analysis (Table 1).

Maintenance rate. The treatment discontinuation rates for any reason during the observation period are shown in Figure 1. Maintenance rate was 49.4 percent (monotherapy: 50.1%, polypharmacy: 48.5%) during the observation period. The withdrawals were due to patient’s choice (30.6%), due to adverse events (15.9% including 10 deaths), the lack of efficacy (15.9%), changing hospitals (20.4%), and other reasons (17.3%). The post-hoc analysis for monotherapy versus polypharmacy demonstrated no significant difference in the maintenance rate between monotherapy and polypharmacy (lrog-rank test: p=1.0). In the subgroup of the initial loading regimen, the maintenance rate was essentially the same (maintenance rate: 47.0%).

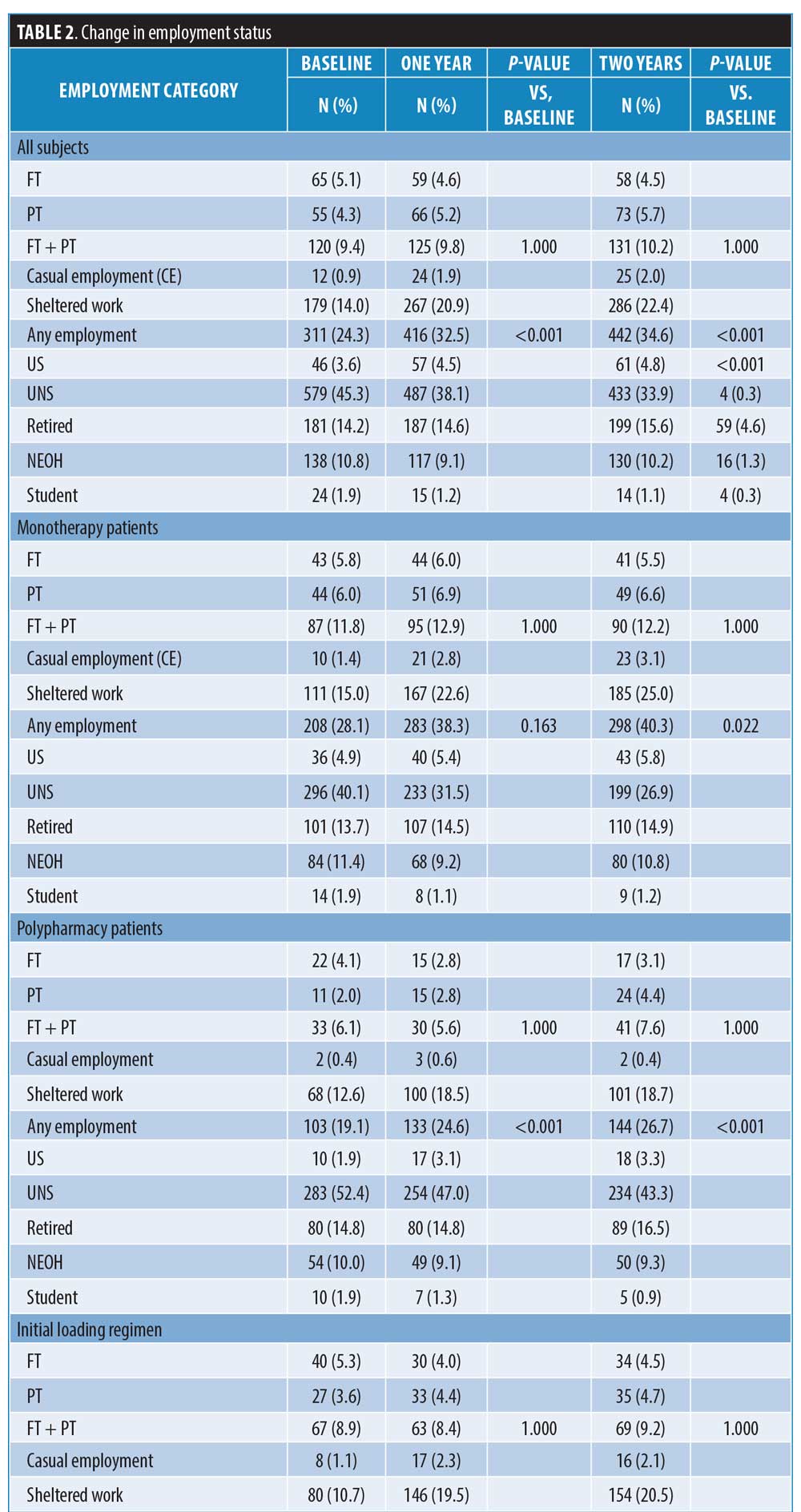

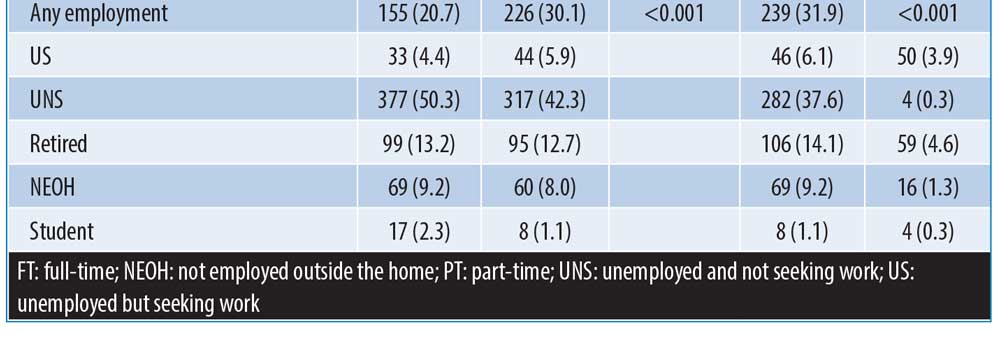

Change of employment status during observation period. During the observation period, the percentage of patients reporting employment increased and that of patients reporting unemployment decreased (Table 2). The percentage of patients who were employed at two years slightly increased from 9.4 to 10.2 percent, applying a restrictive definition (competitive employment: full-time and part-time employment); however, there was no statistical difference. When applying a lenient definition (any type of employment: FT+PT+CE+SW), 24.3 percent of patients were employed in some capacity at baseline, 32.5 percent of patients were employed at one year, and 34.6 percent of patients were employed at two years. The percentages of employed patients (any type of employment) were significantly increased both at one year (p<0.001) and at two years (p<0.001). When retirees, UNS, NEOH, and students were excluded from the labor pool (assuming that these people are not part of the potential working population), the percentages of patients showing any type of employment (employment rate for the labor pool) were 87.1 percent (employed/labor pool = 311/357) at baseline, 87.9 percent (employed/labor pool = 416/473) at one year, and 87.9 percent (employed/labor pool = 442/503) at two years. However, the numbers of patients who met the labor pool criteria were significantly increased from 357 (27.9%) at baseline to 473 (37%) at one year (p<0.001) and to 503 (39.32%) at two years (p<0.001). The percentage of patients categorized as unemployed and not seeking work was decreased from 45.3 percent at baseline to 33.9 percent at two years.

Post-hoc analyses for changes in employment status among monotherapy patients and polypharmacy were conducted; 28.1 percent of monotherapy patients were employed in some capacity at baseline, 38.3 percent of patients were employed at one year, and 40.3 percent of patients were employed at two years. The percentages of employed patients (any type of employment) were significantly increased both at one year (p<0.001) and at two years (p<0.001). Regarding the employment rate for the labor pool, the percentages of patients showing any type of employment were 85.2 percent (employed/labor pool = 208/244) at baseline, 87.6 percent (employed/labor pool =283/323) at one year, and 87.3 percent (employed/labor pool = 298/341) at two years. However, the numbers of patients who met the labor pool criteria were significantly increased from 244 (33.0%) at baseline to 323 (43.7%) at one year (p<0.001) and 341 (46.1%) at two years (p<0.001). The percentage of patients categorized as unemployed and not seeking work was decreased from 40.1 percent at baseline to 26.9 percent at two years. Additionally, 19.1 percent of polypharmacy patients were employed in some capacity at baseline, 24.6 percent of patients were employed at one year, and 26.7 percent of patients were employed at two years. The percentage of employed patients (any type of employment) was significantly increased at two years (p=0.022) but did not reach a significant level at one year (p=0.163). Regarding the employment rate for the labor pool, the percentages of patients showing any type of employment were 91.2 percent (employed/labor pool=103/113) at baseline, 88.7 percent (employed/labor pool=133/150) at one year, and 88.9 percent (employed/labor pool=144/162) at two years. However, the numbers of patients who met the labor pool criteria were significantly increased from 113 (20.9%) at baseline to 150 (27.8%) at one year (p<0.001) and 162 (30%) at two years (p<0.001). The percentage of patients categorized as unemployed and not seeking work was decreased from 52.4 percent at baseline to 43.3 percent at two years.

Regarding employment status in the subgroup of initial loading regimen, the results were similar to those from all subjects.

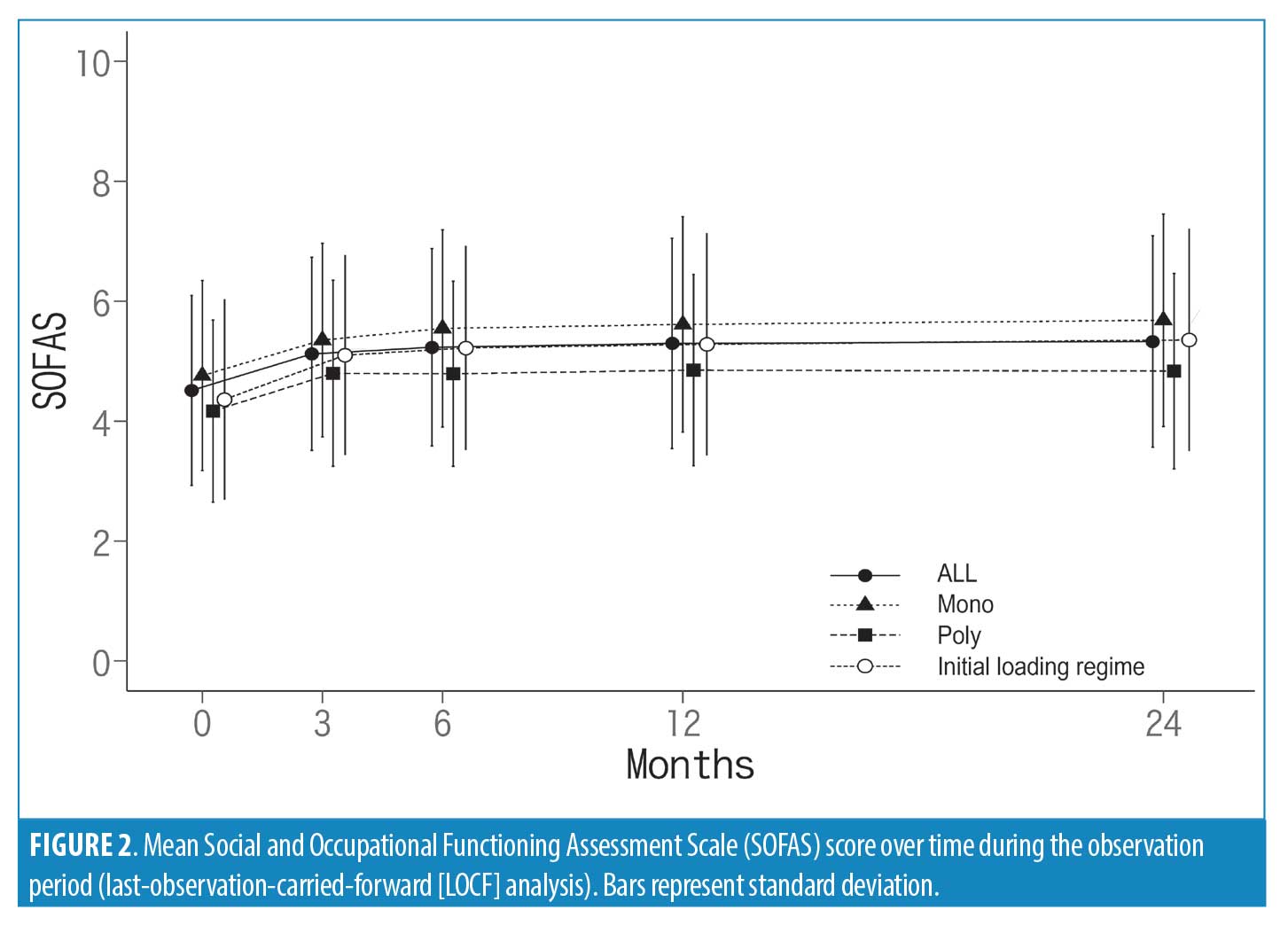

Changes in social function and symptomatic improvement. Changes over time according to treatment in SOFAS score are shown in Figure 2. Analyses for SOFAS were performed with 1,264 patients, excluding 15 who had no baseline SOFAS score. The SOFAS scores increased by 0.8 (SD: 1.7) points at two years from the baseline. GLMM revealed a significant main effect for time in SOFAS (β<0.01; p<0.001). The baseline score of SOFAS (β=0.13; p<0.001) and age (10 years old: β= −0.02; p<0.001) also had significant main effects, while sex did not (male: β= −0.02; p=0.182). The post-hoc Dunnett’s test revealed that there were significant improvements in the SOFAS score between the baseline and all follow-up points (all p<0.001). Polypharmacy (vs. monotherapy) and the interaction with time were added to the model, which showed a significant main effect of polypharmacy (vs. monotherapy: β= −0.05; p=0.004) but not a significant interaction between time and monotherapy versus polypharmacy (p=0.239). Regarding social functional remission, at baseline, 119 (9.4%) patients had already achieved function remission. After baseline, 80 (6.3%) patients achieved remission at six months and an increasing trend was observed at one year (n=252 patients; 19.9%) and two years (n=253 patients; 20.0%).

Regarding social functional changes in the subgroup of initial loading regimen, the results were similar to those from all subjects.

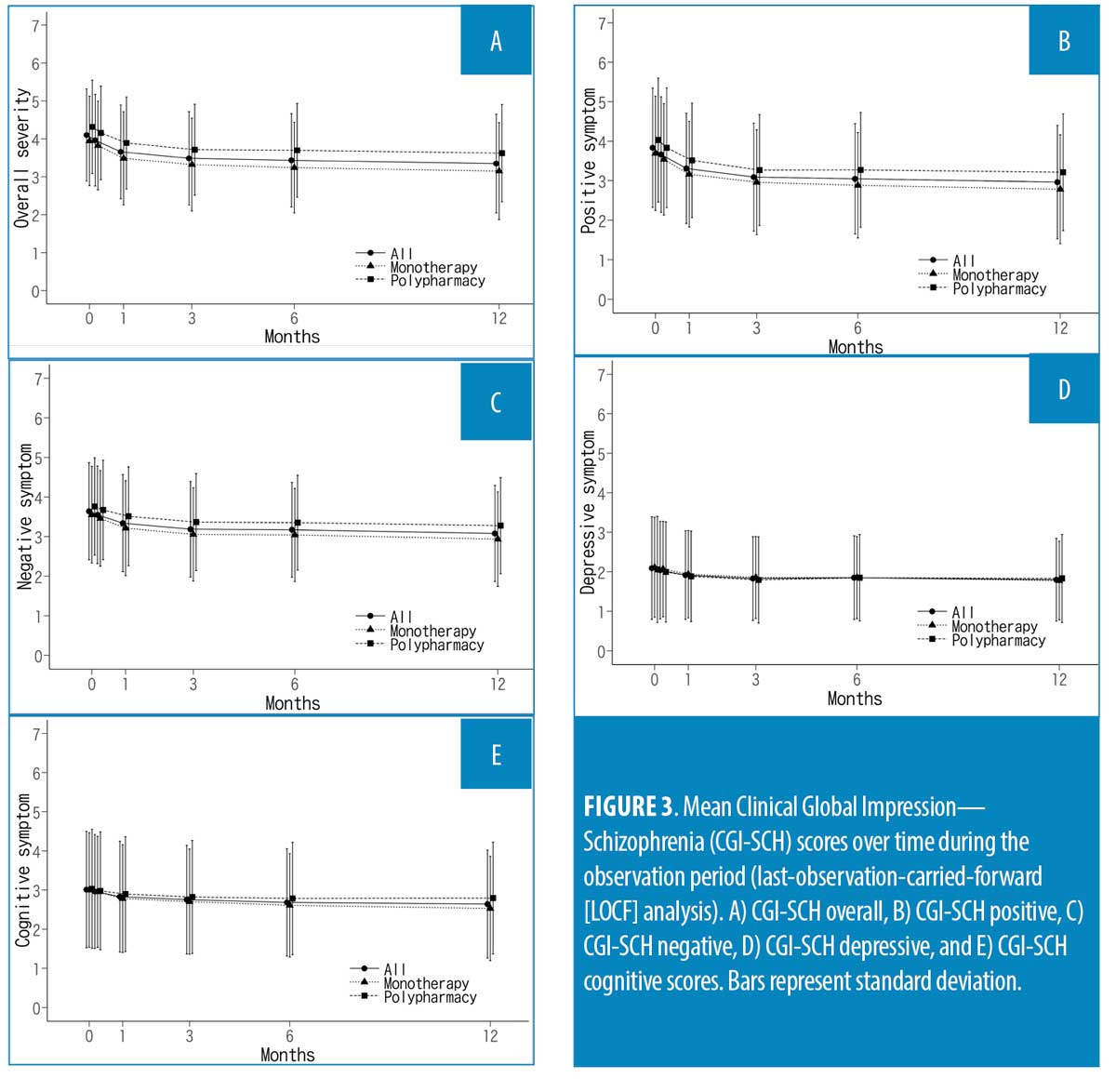

Changes over time according to treatment in CGI-SCH score are shown in Figures 3a to 3e. Analyses for CGI-SCH were performed with 1,279 patients for the overall, 1,277 for the positive, 1,277 for the negative, 1,279 for the depressive, and 1,277 for the cognitive subscales, excluding those who had no baseline CGI-SCH score. The CGI-SCH scores showed symptomatic improvement at one year from the baseline [overall (Figure 3a): −0.8 (SD: 1.3), p<0.001; positive (Figure 3b): −0.9 (SD: 1.4) (Figure 3b), p<0.001; negative (Figure 3c): −0.6 (SD: 1.1), p<0.001; depressive (Figure 3d): −0.3 (SD: 1.1), p<0.001; and cognitive (Figure 3e): −0.4 (SD: 1.2), p<0.001]. GLMM revealed a significant effect for time in CGI-SCH score (overall: β= −0.01, p<0.001; positive: β= −0.02, p<0.001; negative: β= −0.01, p<0.001; depressive: β= −0.01, p<0.001; and cognitive: β= −0.01, p<0.001). The baseline scores also had a significant effect in all subscales (overall: β=0.20, p<0.001; positive: β=0.22, p<0.001; negative: β=0.24, p<0.001; depressive: β=0.31, p<0.001; and cognitive: β=0.28, p<0.001). Sex had no significant effect for any subscales of CGI-SCH. Age showed a significant effect on all subscales (overall: β=0.01, p<0.001; positive: β=0.01, p<0.039; negative: β=0.01, p=0.021; and cognitive: β=0.01, p=0.048) except the depressive subscale (β=−0.01; p=0.287). Polypharmacy (vs. monotherapy) and the interaction with time were added to the model without any significant main effect of polypharmacy visible for any subscales. A significant interaction between time and monotherapy versus polypharmacy was observed only in the cognitive subscale (β=0.01; p=0.027).

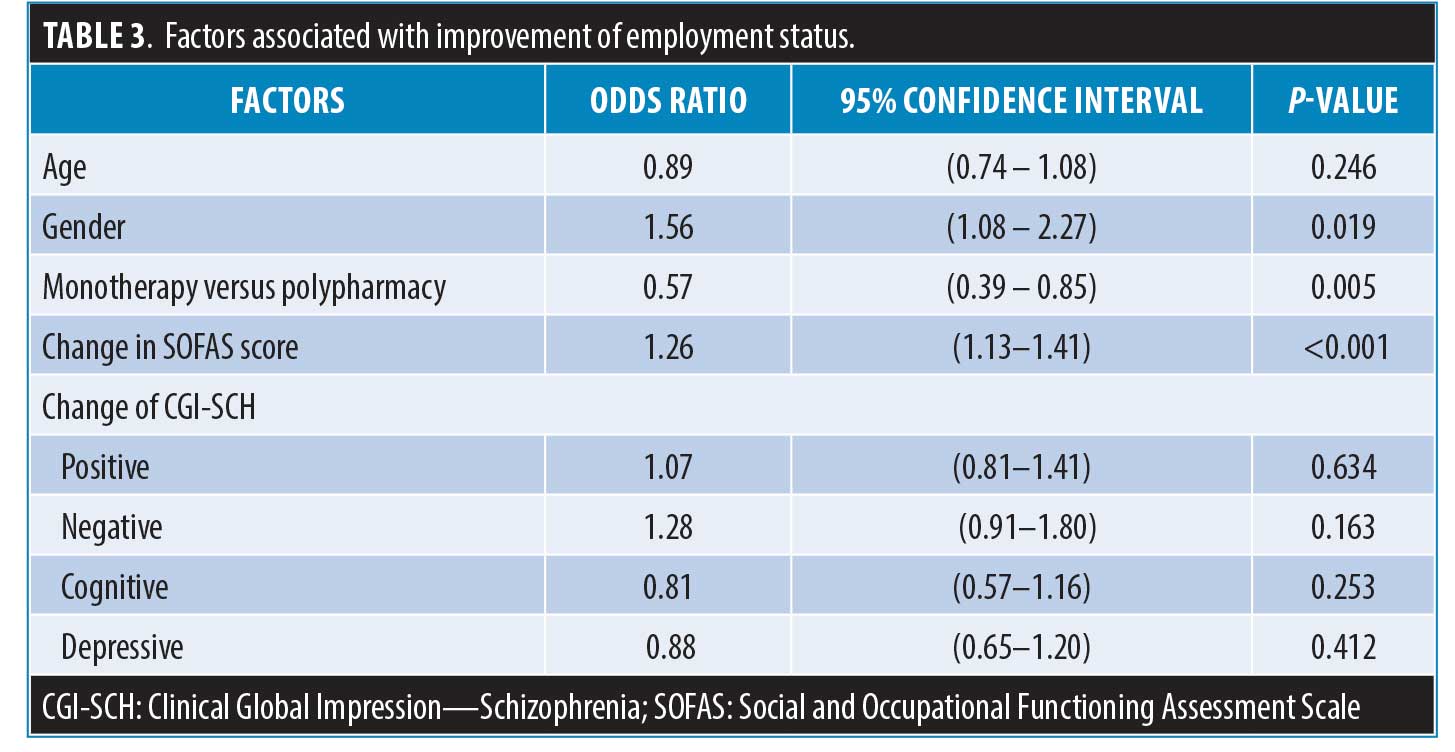

Factors associated with improvement of employment status. All factors modeled and the results of the logistic regression analysis are shown in Table 3. For this analysis, we used observed cases excluding retired subjects, so 535 subjects were analyzed. 195 of 535 subjects showed improvements in employment status during the observation period and 340 of 535 subjects did not show employment status. Logistic regression analysis showed that sex (p=0.019; male sex had favorable effects on employment status), polypharmacy (p=0.005; polypharmacy had unfavorable effects on employment status) and improvement of social function as estimated by SOFAS (p<0.001) were significantly associated with the improvement of employment status (Table 3). On the other hand, age and the improvement of schizophrenic symptoms were not significantly associated with an improvement in employment status.

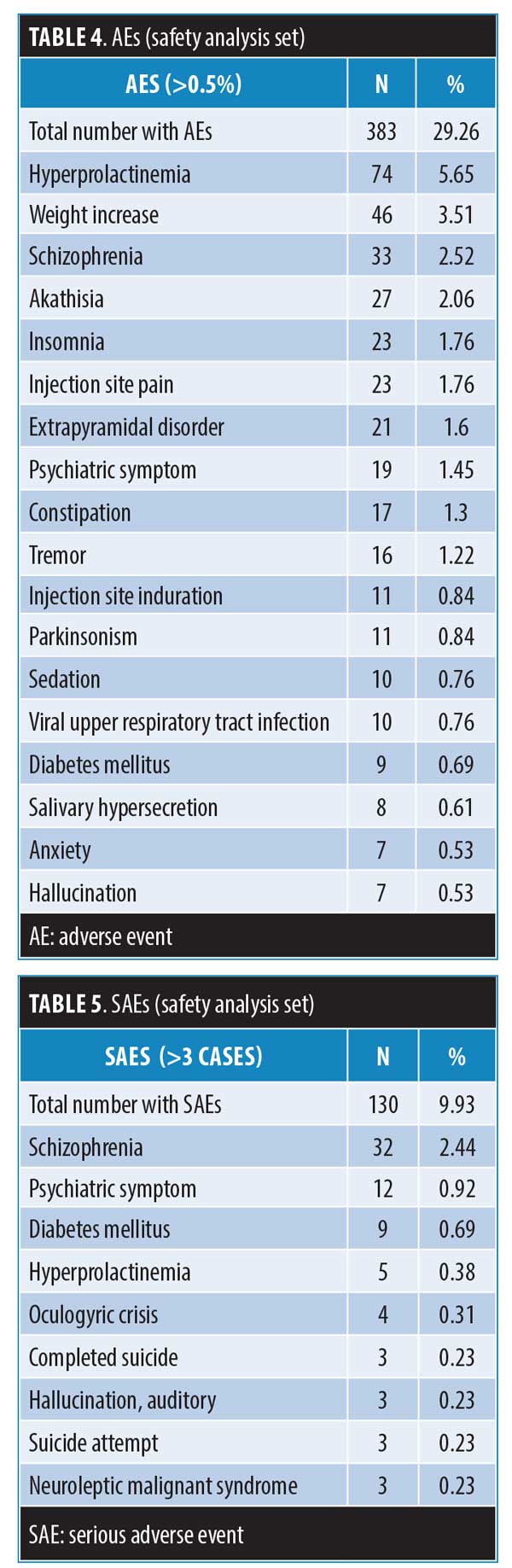

Safety. In total, 29.26 percent of patients experienced at least one AE (n=383 events). Tables 4 and 5 show AEs occurring in more than 0.5 percent of patients. The serious AEs (SAEs) occurring in three cases or more are also listed in Table 3. The most commonly reported AEs were hyperprolactinaemia (5.65%), weight increase (3.51%), schizophrenia (2.52%), akathisia (2.06%), insomnia (1.76%), and injection site pain (1.76%). A total of 9.93 percent of patients experienced at least one SAE (n=150 events). The most commonly reported SAE was schizophrenia (2.44%). Tardive dyskinesia was not reported, but three cases of malignant neuroleptic syndrome were reported as SAEs. Thirteen deaths were reported during the two-year observation period. Causes of death were cardiovascular events (n=4), suicide (n=3), 0.14%), asphyxia (n=2), cerebral hemorrhage (n=1), hepatic failure (n=1), traffic accident (n=1), and sudden death (n=1). Regarding safety data in the subgroup of the initial loading regimen, the results were similar to those from all subjects.

Discussion

In this two-year surveillance study, we found that patients with schizophrenia treated with PP1M showed improvements in social function and employment status accompanied by symptomatic improvement. Developments of pharmacotherapy have contributed to symptomatic improvement and better stability in patients with schizophrenia. Achieving symptomatic remission is a prerequisite for a satisfying level of overall functioning of patients with schizophrenia.20 Although good functioning or functional outcome can be understood to be the primary stage before the achievement of recovery, more demanding and longer-term phenomenon than functional outcome, it is also an important factor in achieving recovery as a treatment goal for schizophrenia.20 Employment status and social function are important functional outcomes in severe mental illness including schizophrenia.1–6, 20 Therefore, our results suggest that PP1M treatment would improve not only schizophrenic symptoms but also functional outcomes, including employment status, and have the possibility of contributing to recovery in patients with schizophrenia.

The strong points of our surveillance are as followings: 1) results obtained during relatively long-term observation (2 years), and 2) results obtained from patients with minimum exclusion criteria under routine clinical settings. Since schizophrenia often requires long-time treatment and shows clinical and biological heterogeneity, the results of this surveillance provide strong support of the clinical usefulness of antipsychotic agents.

A previous study demonstrated that PP1M treatment was associated with prompt and sustained improvement in functioning and employment status among patients with schizophrenia.13 However, we applied the same category of employment status based on the BLS definition that was used in the previous PAL-ER study demonstrating improvement of employment status in schizophrenia.17,21 We mainly discuss the comparison between this surveillance research and the previous PAL-ER study. Similar to in the previous study, we found a significantly improved employment rate during the observation period. Since the observation period of this surveillance (two years) is longer than the previous one (one year), the present results corroborate those of the previous study demonstrating favorable effects of paliperidone treatment on employment status. In this surveillance, the employment rate (any employment) increased from 24.3 percent at baseline to 32.5 percent (at one year), and 34.6 percent (at two years). On the other hand, the employment rate of the previous study increased from 10.0 percent at baseline to 18.8 percent at one year.21 The employment rates at baseline are different between two studies; however, the increases in employment rates of the two studies were essentially the same. Importantly, our results indicated that improved employment status could remain for the next one year (from one year to two years). In addition, the percentage of UNSW was decreased from 45.3 percent at baseline to 38.1 percent at one year and 33.9 percent at two years. Essentially, the same phenomenon was observed in the previous PAL-ER study.21 According to the BSL definition, UNSW individuals are not included in the labor pool.17 Therefore, the decreased population of UNSW could contribute to the increment of the labor pool. Indeed, we found an increment in the number of patients who met the definition of the labor pool during the observation period. Even though employment is not achieved, the increased labor pool might be a worthy outcome for community and society. For patients, the feeling of being able to seek employment might foster pride and self-esteem and might be a worthy outcome.

Post-hoc analyses for changes in employment status in monotherapy patients and polypharmacy patients suggested that monotherapy patients should show better employment status than polypharmacy patients. However, the this is an observational surveillance; therefore, the causality between polypharmacy and worse employment status remains to be clarified.

As mentioned above, this was a surveillance study without a control group and the support system available to the patients varied by their community; thus, the improvement of employment status could not be causally attributed to the PP1M treatment. This is one of limitations of this surveillance study, and the results should be interpreted carefully. Further research with a control group is essential to clarify the causal relationship between the change in employment status and pharmacotherapy. However, despite its limitations, we believe that accumulated evidence of favorable effects of pharmacotherapy in the real world are also important. Because of the cyclic nature of schizophrenia, one would argue that improved employment status could be explained by the ”regression to the mean” phenomenon. A large portion of patients were in a worse phase of their disease when they entered the survey, but they returned to a more normal state toward the end of the survey. This would be possible; however, a previous database study reported that the monthly relapse rates are estimated to be 3.5 to 11 percent per month for patients with schizophrenia.22 Another recent study reported that the relapse rate at one, two, and three years after hospital discharge were 33.0 percent, 29.8 percent, and 16.4 percent, respectively.23 Considering the risk of relapse during observation, if one would accept a ”regression to the mean” hypothesis, one would expect about 30 percent of patients with relapse during two years of observation. Since relapse seriously disturbs functional outcomes including employment status, the “regression to the mean” effect is unlikely to account for the magnitude of the observed effect in this surveillance.

The logistic regression analysis demonstrated that sex (male), monotherapy, and improvement of social function are associated with schizophrenia. Several factors are associated with functional outcome and employment status in schizophrenia, such as previous history of successful employment, patient education, severity of negative symptoms, cognitive functions, and cognitive behavioral training.3–6,9–11,20

Although previous studies have demonstrated a better outcome of the disorder in women with schizophrenia,28 our study found that men exhibited better outcomes in terms of employment status. Despite the recent increment of the employment rate in women, men still show higher employment rates than women in the general population. We speculate that the better employment status of men having schizophrenia should be affected by such an environmental tendency. We also expected that early symptomatic improvements would be associated with improvements in employment status. However, the results indicated that the improvement of employment status should be linked with the enhancement of social function but not with symptomatic improvement. We speculate that the symptomatic improvement caused by antipsychotics might contribute to the improvement of employment via the improvement of social function rather than the direct effects on employment status. Indeed, previous studies have indicated that antipsychotics would not have direct effects on social skills and cognitive function intimately associated with employment in patients with schizophrenia.2,11 As mentioned above, we cannot mention about the causal relationship between improved social functional outcomes including employment status because of the study design. However, some studies have suggested that symptomatic improvement and stability should support the ability to work and be employed.20 Our previous study demonstrated that the early improvement of positive symptoms was associated with later functional remission.24 These data support that symptomatic control and stability should contribute (even if indirectly) to better functional outcomes and employment status. Regarding symptomatic stability, relapse prevention should be most important, and poor adherence to medication has been reported as the most important risk factor related to relapse.22,23 LAI treatment is one of the options with which to achieve full adherence to medication and is a useful method for relapse prevention.12 Taken together, we think that PP1M treatment has favorable effects on functional outcomes including employment status via the improvement of social function and symptomatic stability.

Regarding another functional outcome in this surveillance study, social function evaluated by SOFAS score also showed improvement during the observation period. Regardless of taking monotherapy or polypharmacy, significant improvements in social function were found at three months and were maintained during the two-year observation period. Although the GLMM showed a significant time effect, the estimated effect size was small; one explanation for this is the nonlinear relationship between the time and improvement of SOFAS. A large portion of the improvement in SOFAS score was observed within the three months, which flattened out at further time points, and this might reflect the small effect size. Importantly, the social functional remission rate was also significantly increased. Patients showing social functional remission (SOFAS score≥61 points maintained for more than six months) composed 19.9 percent at one year and 20.0 percent at two years. The data suggested that PP1M is likely to improve and maintain social function.

Regarding symptomatic improvement, improvements were observed within the first month of treatment, and improved symptoms were maintained over the first year. This is consistent with the results of previous trials of PP1M.12 Although, the evaluation of CGI-SCH was done only during the first year, maintenance of fictional outcome during the next year might suggest the possibility of well-controlled schizophrenic symptoms during the two-year observation period. This would support the long-term efficacy of PP1M treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Unlike social functioning outcomes, there were interactions between the improvement course and monotherapy versus polypharmacy in all domains of schizophrenic symptoms. However, this was an observational surveillance study. The causal relationship between polypharmacy and worse efficacy outcomes remains to be clarified. It would be possible that patients with polypharmacy, for example, would have a more severe form of schizophrenia; consequently, physicians combine antipsychotics in these cases. This would also explain the unfavorable effects of polypharmacy on employment status.

The safety data in the present surveillance are generally concordant with the safety profile of PP1M documented in previous studies,12 with no unexpected findings from long-term treatment and a safety profile including mortality rate consistent with the known pharmacological profile of PP1M.

Finally, another limitation of this surveillance not mentioned above is that almost half of the patients did not complete the two-year observation period, so their last observation was carried forward. If noncompletion is correlated with employment and social functioning, then the results could be biased. The maintenance rates of PP1M treatment were 59.9 percent at one year and 49.4 percent at two years. In schizophrenia, estimated one-year rates of treatment discontinuation or interruption were reported to range from 40 to 75 percent;25 therefore, the maintenance rate of this surveillance seems to be a standard maintenance rate of antipsychotics. However, previously, our study of PAL-ER with a similar study design and population reported a higher maintenance rate during one year of 65 percent relative to that of this study.24 Since a recent community-based study reported a lower discontinuation rate of LAI when compared with oral antipsychotics,26 the observed lower maintenance rate of PP1M than that of PAL-ER seems to be unlikely. At present, we have no clear explanation for this issue. The discontinuation observed in this surveillance was mainly found during the early phase of the observation period, within 90 days after the first administration of PP1M. During the six-month Japanese early postmarketing phase vigilance period for PP1M, 32 deaths were reported.27 Although later analysis revealed that the observed death rate does not necessarily result from a risk with PP1M treatment in Japanese patients,27 some Japanese physicians and patients have concerns about the safety of PP1M. We speculate that such concerns might affect dropout during the early phase of this surveillance.

Conclusion

The results of this surveillance suggest that PP1M treatment would improve not only schizophrenic symptoms but also functional outcomes, including employment status, and have a possibility of contributing to recovery in patients with schizophrenia via social functional improvement. Improvements in functionality as observed with PP1M treatment could be important clinical considerations when an antipsychotic agent is being selected for patients with schizophrenia.

References

- Kane JM. An evidence-based strategy for remission in schizophrenia. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69 Suppl 3:25–30.

- Chow CM, Cichocki B. Predictors of job accommodations for individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2015;59(3):172–184.

- Charzyńska K, Kucharska K, Mortimer A. Does employment promote the process of recovery from schizophrenia? A review of existing evidence. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2015;28(3):407–418.

- Krupa T. Employment, recovery, and schizophrenia: Integrating health and disorder at work. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;28(1):8–15.

- Rosenheck R, Leslie D, Keefe R, et al. Barriers to employment for people with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):411–417.

- Salkever DS, Karakus MC, Slade EP, et al. Measures and predictors of community-based employment and earnings of persons with schizophrenia in a multisite study. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(3):315–324.

- Marwaha S, Johnson S, Bebbington P, et al. Rates and correlates of employment in people with schizophrenia in the UK, France and Germany. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:30–37.

- Sado M, Inagaki A, Koreki A, et al. The cost of schizophrenia in Japan. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:787–798.

- Latimer E. Economic considerations associated with assertive community treatment and supported employment for people with severe mental illness. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2005;30(5):355–359.

- Suijkerbuijk YB, Schaafsma FG, van Mechelen JC, et al. Interventions for obtaining and maintaining employment in adults with severe mental illness, a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:CD011867.

- Carmona VR, Gómez-Benito J, Huedo-Medina TB, Rojo JE. Employment outcomes for people with schizophrenia spectrum disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2017;30(3):345–366.

- Morris MT, Tarpada SP. Long-acting injectable paliperidone palmitate: a review of efficacy and safety. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2017;47(2):42–52.

- Zhang H, Turkoz I, Zhuo J, et al. Paliperidone Palmitate improves and maintains functioning in Asia-Pacific patients with schizophrenia. Adv Ther. 2017;34(11):2503–2517.

- Mihaljevic-Peles A, Sagud M, Filipcic IS, et al. Remission and employment status in schizophrenia and other psychoses: One-year prospective study in Croatian patients treated with risperidone long acting injection. Psychiatr Danub. 2016;28(3):263–272.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Text Revision, DSM-IV-TR. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- Haro JM, Kamath SA, Ochoa S, et al. The Clinical Global Impression—Schizophrenia scale: a simple instrument to measure the diversity of symptoms present in schizophrenia. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2003;(416):16–23.

- U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. How the government measures unemployment. Available at: http://www.bls.gov/cps/cps_htgm.htm. Accessed November 25, 2018.

- Gopal S, Gassmann-Mayer C, Palumbo J, et al. Practical guidance for dosing and switching paliperidone palmitate treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2010;26(2):377–387.

- Schennach R, Musil R, Möller HJ, Riedel M. Functional outcomes in schizophrenia: employment status as a metric of treatment outcome. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2012;14(3):229–236.

- Kozma C, Dirani R, Canuso C, Mao L. Change in employment status over 52 weeks in patients with schizophrenia: an observational study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(2):327–333.

- Weiden PJ, Olfson M. Cost of relapse in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1995;21(3):419–429.

- Wu F, Huang Y, Zhou Y, et al. Factors influencing relapse in schizophrenia: a longitudinal study in China.Biomedical Research. 2017;28(9):4076–4082.

- Nakagawa R, Ohnishi T, Kobayashi H, et al. The social functional outcome of being naturalistically treated with paliperidone extended-release in patients with schizophrenia. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;;11:1511–1521.

- Samtani MN, Sheehan JJ, Fu DJ, et al. Management of antipsychotic treatment discontinuation and interruptions using model-based simulations. Clin Pharmacol. 2012;4:25–40. S32735. Epub 2012 Jul 16. Erratum in: Clin Pharmacol. 2012;4:51.

- Verdoux H, Pambrun E, Tournier M, et al. Risk of discontinuation of antipsychotic long-acting injections vs. oral antipsychotics in real-life prescribing practice: a community-based study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2017;135(5):429–438.

- Pierce P, Gopal S, Savitz A, et al. Paliperidone palmitate: Japanese postmarketing mortality results in patients with schizophrenia. Curr Med Res Opin. 2016:32(10):1671–1679.

- Leung A, Chue P. Sex differences in schizophrenia, a review of the literature. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2000;101(401):3–38.