by Julie P. Gentile, MD; Kristy S. Dillon, MS, PCC-S; and Paulette Marie Gillig, MD, PhD

by Julie P. Gentile, MD; Kristy S. Dillon, MS, PCC-S; and Paulette Marie Gillig, MD, PhD

Dr. Gentile is Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Wright State University and Medical Director at Consumer Advocacy Model, a community mental health center treating patients with mental illness, substance use, and co-occurring disabilities including traumatic brain injury in Dayton, Ohio; Ms. Dillon is a Professional Clinical Counselor and Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment Counselor at Consumer Advocacy Model, Dayton, Ohio; and Dr. Gillig is a Professor with the Department of Psychiatry at Boonshoft School of Medicine, Wright State Univeristy in Dayton, Ohio.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(2):22–29

Department Editor: Paulette Gillig, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Boonshoft School of Medicine, Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio

Editor’s Note: The patient cases presented in Psychotherapy Rounds are composite cases written to illustrate certain diagnostic characteristics and to instruct on treatment techniques. These composite cases are not real patients in treatment. Any resemblance to a real patient is purely coincidental.

Funding: No funding was received for this article.

Financial Disclosures: The authors do not have conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Key Words: Supportive psychotherapy, psychodynamic psychotherapy, dissociation, altered states, counseling, post-traumatic stress disorder, dissociative identity disorder, multiple personalities, DSM-V

Abstract: There is a wide variety of what have been called “dissociative disorders,” including dissociative amnesia, dissociative fugue, depersonalization disorder, dissociative identity disorder, and forms of dissociative disorder not otherwise specified. Some of these diagnoses, particularly dissociative identity disorder, are controversial and have been questioned by many clinicians over the years. The disorders may be under-diagnosed or misdiagnosed, but many persons who have experienced trauma report “dissociative” symptoms. Prevalence of dissociative disorders is unknown, but current estimates are higher than previously thought. This paper reviews clinical, phenomenological, and epidemiological data regarding diagnosis in general, and illustrates possible treatment interventions for dissociative identity disorder, with a focus on psychotherapy interventions and a review of current psychopharmacology recommendations as part of a comprehensive multidisciplinary treatment plan.

Introduction

Dissociative disorders (DDs) were first recognized as official psychiatric disorders in 1980 with the publication of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM III) in 1980. Prior to this, the related symptoms were listed under ‘hysterical neuroses’ in the second edition of the DSM.[1,2] Interestingly, all of the current DDs that have been described were discovered prior to 1900 but decades passed with little study or research of this spectrum of psychiatric pathology. The existence of dissociative disorders is questioned by many in the field of psychiatry, and the diagnosis is not utilized by some clinicians.[3]

Some research within the past five years indicates that DD consist of psychiatric symptoms that are severe and disabling, resulting in high utilization of community resources.[1,3] The costs to patients are significant in the form of personal suffering and impairments in functioning.[4] DDs, along with other complex posttraumatic disorders, are incredibly costly to the mental health delivery system.[1,4,5] Complicating factors include misdiagnosis and under-diagnosis, which may occur due to unfamiliarity with this spectrum of disorders, disbelief that they exist, or lack of knowledge and appreciation of the epidemiology.[1,4] An added layer of complication involves dissociation related to a criminal offense.[1] Despite the belief of some psychiatrists that these disorders are very rare and others who question their existence, some recent prevalence estimates range from 12 to 28 percent in adult outpatients for all DDs.[5]

Dissociation can be interpreted as an “emergency defense,” or a “shut off mechanism.”[6] According to Allen and Smith,[6] it is understood as an attempt by the individual to “prevent overwhelming flooding of consciousness at the time of trauma.” It is argued that the individual subconsciously cannot tolerate being present emotionally during the trauma but cannot control the situation, and therefore protects him- or herself from experiencing it in the moment via dissociation.

Dissociative symptoms are not merely failures of normal neurocognitive functioning, they are also perceived as disruptive, because there is a loss of needed information or as discontinuity of experience.[7] According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR),[8] “the essential feature of the dissociative disorders is a disruption in the usually integrated functions of consciousness, memory, identity, or perception.” The dissociative disorder spectrum is characterized as a collection of long-term, chronic disorders.[7,8]

Dissociation may differ in presentation for each individual and, more significantly, in its “adaptive efficacy.”[6] When an individual experiences trauma, dissociation is an attempt to survive, tolerate, consciously escape, or adapt to the situation. Once the individual has learned to dissociate in the context of trauma, he or she may subsequently transfer this response to other situations and it may be repeated thereafter arbitrarily in a wide variety of circumstances. The dissociation therefore “destabilizes adaptation and becomes pathological.”[6] It is important for the psychiatrist to accurately diagnose DDs and also to place the symptoms in perspective with regard to trauma history. Patients who receive treatment interventions that address their trauma-based dissociative symptoms show improved functioning and reduced symptoms.[4]

CLINICAL VIGNETTE 1: Handling the Emergence of “Alters” During Psychotherapy Sessions

Ms. B was a 28-year-old woman with a diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder (DID) who reported physical and sexual abuse by her mother’s boyfriend throughout her developmental years. She reported being punched, kicked, hit, and whipped with extension cords. She stated that her mother’s boyfriend could be kind to her one moment and quick to anger the next. She also indicated that he abused alcohol and drugs, and enlisted Ms. B to sell drugs for him at a very early age. Her acute symptoms at the time of admission to the clinic were panic attacks, exaggerated startle response, claustrophobia, and self-injurious behavior, which consisted of cutting her abdomen and arms.

After being in weekly psychotherapy with for six months, Ms. B was struggling with what to discuss in the room; she had reported in previous sessions that she used drawing as an outlet to cope with her anxiety and stress so it was recommended she sketch or write her thoughts on paper as a conduit to further discussion and exploration. After several minutes, Ms. B suddenly stopped drawing and was very still. Ms. B did not respond when her name was called. The patient’s eyes were shut, but under her eyelids could be seen shifting horizontally similar to eye activity during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep.

Psychiatrist: What’s your name?

Ms. B: Little Liar

Psychiatrist: How old are you?

Ms. B: Four

Psychiatrist: You seem like a nice little girl to me.

Ms. B: My mom thinks I’m a liar.

Psychiatrist: I don’t think you are a liar. You can talk to me any time you like.

Ms. B: Tom did bad stuff to me. He took me downstairs and showed me lots of guns.”

Psychiatrist: Who is Tom?

Ms. B: My mom’s boyfriend.

Psychiatrist: What was the bad stuff he did to you?

Ms. B: He touched me down there. [points to her buttocks] He told me not to tell anyone. [patient starts to sob]

Psychiatrist: It’s ok for you to tell me what happened. You are safe here; no one will hurt you when you are here. You didn’t do anything wrong.

Ms. B: He made me bleed. I told my mom, but she whipped me anyway.

Psychiatrist: You didn’t do anything wrong. Tom was being bad. He hurt you and so did your mom.

The focus of the intervention is to listen, empathize, and provide validation and reassurance that the patient is currently safe, particularly when the emerging “alter” represents a person who is much younger than the patient’s current age. In addition, the patient (as the “alter”) must be provided the opportunity to tell her story and be heard and supported. Ms. B remained in this “dissociated” state for 30 minutes. Time was spent exploring what made “Little Liar’” feel better, and she indicated that she liked “The Little Mermaid” movie and princesses. This was valuable information to integrate into future sessions, and the patient dissociated into “Little Liar” multiple times over the course of her treatment.

DISSOCIATIVE IDENTITY DISORDER

When dissociation occurs in combination with the following symptoms, the diagnosis of dissociative identity disorder should be considered. See Table 1 for a list of diagnostic characteristics.

Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is a controversial diagnosis within the mental health profession.[9] It is said to be characterized by “the presence of two or more distinct identities or personality states (each with its own relatively enduring pattern of perceiving, relating to, and thinking about the environment and self)…that recurrently take control of the person’s behavior…There is an inability to recall important personal information…which is too great to be explained by ordinary forgetfulness.”[8] DID is the most complicated and theoretically challenging dissociative disorder; it embodies the full range of dissociative phenomena.[6] DID is not caused by alcohol, other substance use, or by medical conditions. It is a complex disorder consisting of posttraumatic, somatoform and depressive symptoms, as well as a variety of dissociative symptoms.[1] Severe dissociative disorders rarely occur in exclusion of additional psychiatric pathology, largely because they occur as a result of trauma, and the effects of trauma are diverse.[6] DID is frequently associated with depressive disorders, somatization disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, and personality disorders.[1,7] Signs of self-injurious behavior should be investigated and addressed (if indicated) as part of the psychiatric assessment and treatment plan.

Dissociative identity disorder (DID) is a controversial diagnosis within the mental health profession.[9] It is said to be characterized by “the presence of two or more distinct identities or personality states (each with its own relatively enduring pattern of perceiving, relating to, and thinking about the environment and self)…that recurrently take control of the person’s behavior…There is an inability to recall important personal information…which is too great to be explained by ordinary forgetfulness.”[8] DID is the most complicated and theoretically challenging dissociative disorder; it embodies the full range of dissociative phenomena.[6] DID is not caused by alcohol, other substance use, or by medical conditions. It is a complex disorder consisting of posttraumatic, somatoform and depressive symptoms, as well as a variety of dissociative symptoms.[1] Severe dissociative disorders rarely occur in exclusion of additional psychiatric pathology, largely because they occur as a result of trauma, and the effects of trauma are diverse.[6] DID is frequently associated with depressive disorders, somatization disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance abuse, and personality disorders.[1,7] Signs of self-injurious behavior should be investigated and addressed (if indicated) as part of the psychiatric assessment and treatment plan.

The individual personality states present in DID may be very different from one another. They may have different names, ages, moods, and functions.[1] Patients with DID frequently experience somatic symptoms, including but not limited to headaches, conversion, pseudoseizures, and gastrointestinal and genitourinary disturbances.[1] This further complicates the diagnosis, and medical conditions as well as additional psychiatric pathology must be considered. The primary personality usually has no recall of alternate identities; the alternate identities or personalities may have some awareness of each other. It is common for one alter personality to hold a central role and be aware of and familiar with all of the others.[1]

Because dissociation frequently co-occurs with severe anxiety and depressive symptoms, it is understandable that the psychiatrist may be focused on the accompanying pathology and inadvertently omit or fail to consider the diagnosis of DID.[1] The associated symptoms should be addressed in the psychotherapy as well as any pharmacologic interventions. The patient experiencing dissociation may be unlikely to report episodes of memory loss unless asked directly during a clinical interview due to embarrassment of the symptoms or the resultant consequences. According to Coons,[1] altered personality states are less likely to occur while in the room with the psychiatrist, possibly due to decreased level of stress in this setting or alternatively because the psychiatrist is not inquiring about such symptoms. Directed questions may include inquiring about lapses in memory, reports of abnormal behavior by those close to the patient, or finding objects or possessions the patient cannot recall acquiring. Experts in DID believe that a psychiatrist should not make the diagnosis unless the dissociation is observed or a change from one personality to another occurs in the room.[1][

]In addition, the altered states should be consistent in their presentation. Signs of a switch to an altered state include trancelike behavior, eye blinking, eye rolling, and changes in posture. Switching is frequently associated with a high level of stress, and may be associated with severe symptoms of depression, extreme anger, or sexual stimulation.[1] Other psychiatric and medical diagnoses, which should be ruled out in the evaluation process, include but are not limited to hypnotic states, seizure activity with personality change, psychosis with ego fragmentation, and rapid cycling bipolar disorder.

Childhood trauma, and in particular sexual or physical abuse, is nearly always present in individuals with DID.[1] The prevalence of DID is higher in females than in males, although specifics are lacking and there is a need for more research of prevalence rates. Myrick et al[5] reported that although most studies consist of patients 35 years or older, younger patient populations reported significant dissociative symptoms and destructive behaviors but were less likely to be diagnosed with dissociative disorders. Although DID may occur in patients under the age of 18 years, it is most commonly diagnosed in patients in their third or fourth decade of life.[1] Altered personality states may number between one and 50, but the average is 13 altered states.[1]

PRACTICE POINT: DEVELOPMENTAL PROCESSES OF DISSOCIATION

Early maltreatment experiences can produce various outcomes; this is a multifactorial process, which will be managed differently by individuals based on many elements including but not limited to attachment styles, social supports, and quality and severity of the maltreatment. The age of the individual at the time of the abuse is also a critical component due to the developmental processes that, under other circumstances, would normally occur at that time. In addition, the age at the beginning and the ending of the abuse is significant as it “encompasses the sequence of developmental stages spanned by the maltreatment…and should influence which developmental tasks are most disrupted.”[10] Although there is no conclusive data in this area, it appears as if vulnerability to dissociation increases if the abuse occurs at earlier developmental stages.

During infancy and toddler years, the major developmental tasks are as follows:[10]

• Discovery of the world of people and objects

• Establishment of secure social relationships within the family

• Establishment of a basic sense of self

• The development of an autonomous sense of awareness

• Acquisition of an initial sense of right and wrong (good and bad).

Because children at these early stages have such limited coping and self-regulatory capability, they are easily overwhelmed.[10] Infants will tend to exhibit disruption of feeding and sleep patterns; toddlers will typically show significant regression.

Core development for preschoolers (ages 2–5 years) involves integration of self within social context and norms.[10] During these years, children progress from simple physical exploration of the world to pretend and symbolic play. The child begins to develop an understanding of reality and often uses denial as a coping strategy. The capacity for dissociation increases significantly during these years, and this may be related to the introduction of the use of fantasy and imagination. Abuse during this time disrupts self-regulation of emotion as well as early organization of self-perception. One theory is that maltreatment during preschool years is correlated with increased use of denial and dissociation as core coping strategies. The vulnerability may be further increased if authority figures in the child’s life encourage the use of denial (i.e. “Don’t worry. The shot will not hurt.”[10]

The elementary years involve tasks such as further development of self, including psychological characteristics (i.e., thoughts, feelings, and motives).[10] Children develop the capacity for shame and pride during this period and can view themselves as “objects.” Friends and peers become increasingly critical, and evaluations of others become integrated into self-perception. Maltreatment during these years disturbs socialization and causes the individual to experience guilt, shame, and confusion.

Adolescence brings physical growth and change including puberty, which involves major psychological readjustments. The focus of same-sex friendships converts to opposite-sex exploration of intimacy and mutuality.[10] Identity formation requires integration of complex views of self, unified with peer evaluation of significant others. Maltreatment is complicated by the disruption of the defining of self as well as the increased opportunity for maladaptive coping,, such as substance use, sexual acting out, and other risk taking and self-destructive behaviors.

For the psychiatrist, it is important to be cognizant that maltreatment during developmental years is strongly correlated with relationship dysfunction, especially for female victims in the context of incest.[3,4,10] Conflict with others and difficulty with boundaries as well as frequent re-victimization in subsequent relationships are all too common. Emotional dysregulation occurs frequently in this subset and may be the precipitant of psychiatric treatment.[4,10]

The proposal for DID in the DSM-V includes utilization of a Likert response scale of the patient’s rating for the following statements:[11]

• I find myself staring into space and thinking of nothing.

• People, objects, or the world around me seem strange or unreal.

• I find that I did things that I do not remember doing.

• When I am alone, I talk out loud to myself.

• I feel as though I were looking at the world through a fog so that people and things seem far away or unclear.

• I am able to ignore pain.

• I act so differently from one situation to another that it is almost as if I were two different people.

• I can do things very easily that would usually be hard for me.

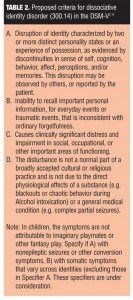

Information provided in Table 2 delineates the differences between the criteria for DID and the proposed revisions for the upcoming fifth edition of the DSM to be published in May of 2013.

CLINICAL VIGNETTE 2: Helping the Patient View the Diagnosis in a Positive Way

Ms. C was a 35-year-old woman with DID who was status-post motor vehicle accident during childhood wherein she suffered minor physical injuries but witnessed the death of both parents. Subsequently, she spent the remainder of her developmental years in foster homes and reported multiple incidents of sexual abuse during this time. Ms. C did not smoke tobacco nor did she drink alcohol or use other substances. However, she shared that sometimes she knew that she had dissociated into one of the alter personalities who drank, because she found empty beer cans in her home.

Ms. C reported that one time she came home and “someone had decided to paint the bedroom” but she had no recollection of this. Sometimes when she dissociated she knew she was gone for several days because when she came home, her dogs were out of food and water and they had “destroyed the house.” Ms. C often came to sessions with bruises, scrapes, and swollen knuckles, but did not know how or where she incurred the injuries. The alter that she described as the “Protector of the Others” would often get into physical altercations with other people when she felt threatened or the need to defend herself. During these episodes she reported receiving strange messages on her voicemail from people she did not recognize, telling her that they had had “a great time” with her. She also had phone numbers of people that she did not recognize saved in her phone. She reported having a urinary tract infection once, and “feeling like I had been sexual with a man,” but had no memory of it. The “Protector of the Others” not only used substances but was seductive and promiscuous. She stated, “I have to pretend a lot. I have to act like I know what’s going on when I really don’t. People talk to me about things I’ve done, and I don’t remember any of it. It’s humiliating.”

One of the most important interventions during the treatment was to reframe the DID as a positive, rather than a negative. The patient had always viewed her diagnosis as a sign that she was “crazy.” This can be reframed as a constructive, very complex system that developed to help her survive the trauma of the motor vehicle accident, the premature and unexpected loss of her parents, and the sexual abuse. Reframing the dissociation helped establish a deeper level of trust in the therapeutic alliance. Expressing empathy, compassion, and nonjudgment was also very important to counter the negative experiences the patient had with past treatment providers.

When treating patients with DID, much time will be spent exploring different alter personalities and identifying the role each plays in the system. Throughout the psychotherapy the use of motivational interviewing, open-ended questions, and reflective listening in the room may be helpful depending on the patient’s acute symptoms.

PRACTICE POINT: DEVELOPMENTS IN PSYCHOTHERAPY

The treatment plan designed for patients with dissociative disorders (DD) is vital since this patient population is a financial burden as utilizers of the highest number of psychotherapy sessions compared to those with all other psychiatric disorders.[4] In a study in Massachusetts, patients with DID made up only 2.6 percent of the sample but accounted for 33.5 percent of the total Medicaid inpatient costs.[3,4] In addition, there were high rates of suicidal and self-injurious behavior among patients with DID compared to patients with other disorders, leading to long courses of treatment in outpatient psychiatric clinics.

There is evidence that patients with DD may drop out of cognitive behavioral treatments, indicating that programs that do not specifically address dissociation may not be well tolerated.[4] In a study by Tamar-Gurol et al,[12 55] percent of patients with DD prematurely dropped out of treatment for drug abuse compared to 29 percent of those without DD. Somer[13] found that dissociation predicted lower rates of abstinence among heroin users in treatment and led Somer to conclude that “without a thorough resolution of trauma-related dissociation, optimal treatment outcome is compromised.”

A report of 36 international DD experts advised a carefully staged multilateral treatment structure. The first stage emphasized “emotion regulation, impulse control, interpersonal effectiveness, grounding, and containment of intrusive material.”[4] In the second stage of treatment, the experts recommended the use of exposure/abreaction techniques (though modified to avoid overwhelming the patients) balanced with core interventions. The last stage of treatment was less specific and individualized according to the patient’s symptoms and specific needs.

A recent review by Brand et al[4] of the DD treatment literature concluded that when treatment is specifically adapted to address the complex traumas and high level of dissociation among patients with this spectrum of psychiatric disorders, even severely affected patients improve.[4] A course of psychotherapy for patients with dissociative disorders may be complicated and sometimes require an eclectic approach or periods of change between various approaches. During periods of acute stressors, frequent dissociation and/or severe depression and anxiety, supportive interventions (crisis interventions and shoring up existing coping skills and strategies) are a better fit; during periods of relatively mild symptoms, a psychodynamic approach may be utilized (focusing on self-reflection and self-examination).[14,15]

Psychodynamic psychotherapy uses self-reflection and self-evaluation while the work in the room is achieved due to the therapeutic alliance and inter-relationship with the psychiatrist. The expectation is that the patient will explore effective coping strategies and relationship patterns. The psychiatrist attempts to reveal the unconscious components of the patient’s maladaptive functioning and attends to resistance as it reveals itself. Facilitation of change is accomplished over time when a trusting alliance is established, resistance is managed, and deeper understanding has developed.

The issue of integration should be explored in a psychotherapy relationship. Integration at a basic level may be defined as “acceptance/ ownership of all thoughts, feelings, fears, beliefs, experiences and memories (often labeled as personalities) as me/mine.” Some consider it a necessary part of trauma recovery and exploration in the psychotherapy; others state it is a personal choice for each individual patient. In the process of integration, the patient takes responsibility and ownership for all parts of self. Potentially, the most critical element is complete acceptance of the whole person including all dissociated parts. As Downing describes,[16] “integration is more than about personalities…it is a process not an event. It occurs throughout therapy (and outside of therapy) as dissociated aspects of one’s self become known, accepted, and integrated into normal awareness.”

CLNICAL VIGNETTE 3: Reacting to the Presence of an Alter in Group Therapy

Ms. H was a 42-year-old, divorced woman with DID who was referred for mental health treatment of depression, anxiety, flashbacks, gaps in her memory, loss of time, and paranoia. At the time of her assessment, Ms. H alleged that she had been molested for a several years during developmental years by various perpetrators, including her brother and father. During her teenage years, the patient’s mother who reportedly had history of schizophrenia (paranoid type), would kick her out of the house, and the patient would live with the families of school friends. The patient’s significant other attended the intake appointment with the patient’s permission and shared information on the five alter personalities that she had interacted with over several years.

The various alter personalities played different roles in helping the patient function in the world. Each alter had compartmentalized certain emotions and were void of others. One of the alters held most of the memories of abuse and expressed most of the sadness. Another was described as the “The Primary” alter who was angry, outspoken, suspicious, aggressive and defensive.

After six months of weekly psychotherapy supplemented with group therapy, Ms. H’s father (and alleged perpetrator) passed away, causing an exacerbation of anxiety and conflicted emotions. This proved to be a devastating recurrence of trauma for the patient and became the precipitating factor for the symptoms of DID to emerge in the room. The first indication that the patient was beginning to dissociate in treatment was when she showed up at the office one day late for a psychotherapy process group that she had been attending consistently in addition to her individual psychotherapy. The receptionist reported that the patient looked “different” and “acted like she was intoxicated.”

The following week, the patient came to the group and had a different hair style and introduced herself with a different name when she checked in to group. She appeared anxious and spoke using “street talk.” Ms. H had dissociated into one of her alter personalities, and so the focus in the room was on the provision of support, reassurance, and safety.

Ms. H: [leaning over and whispering] I don’t think I’m supposed to be here.

Psychiatrist: It’s okay for you to be here. This is a safe place. No one here will hurt you.

Ms. H: I think they are scared of me. [looks at the other group therapy attendees]

Psychiatrist: What makes you think they are scared of you?

Ms. H: When I sat down, they moved away from me.

Psychiatrist: They aren’t scared of you; they were making room for you. You are safe here.

Ms. H: I don’t trust anyone. [she looks up at the group] I don’t know what y’all think, but you can’t trust anyone.

Psychiatrist: You’ve been hurt by people in the past, but no one here wants to hurt you.

After a few minutes, the patient got up and left the group, stating she needed to use the restroom, but she did not return.

PRACTICE POINT: DEVELOPMENTS IN PHARMACOTHERAPY FOR DID AND OTHER DISSOCIATIVE DISORDERS

Brand et al[4] reports that atypical (or second generation) antipsychotic drugs that block both dopamine (D2) and serotonin (5-HT2A) receptors may be of use in treating complex trauma cases with psychotic features, although care should be taken to distinguish auditory hallucinations, which originate from an external locus, versus internal “voices.” Opioid antagonists, such as naltrexone have also shown some promise in the treatment of dissociative symptoms. The mu and kappa systems may be associated with symptoms of analgesia. Stress-induced analgesia, a form of dissociation, has been shown to be mediated by the mu opioid system.[4]

Most medications (e.g., antidepressants, anxiolytics) are prescribed for comorbid anxiety and mood symptoms, but these medications do not specifically treat the dissociation. Presently, no pharmacological treatment has been found to reduce dissociation.[18] Although antidepressant and anxiolytic medications are useful in the reduction of depression and anxiety and in the stabilization of mood, the psychiatrist must be cautious in using benzodiazepines to reduce anxiety as they can also exacerbate dissociation.[17,18] In treating patients with DID, there are reports of some success with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase inhibitors, beta blockers, clonidine, anticonvulsants, and benzodiazepines in reducing intrusive symptoms, hyperarousal, anxiety, and mood instability.[17,18] Atypical (or second generation) antipsychotics have also been used for mood stabilization, overwhelming anxiety, and intrusive posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in patients with DID, as they may be more effective and better tolerated than typical (or first generation) antipsychotics. Other possible suggestions for pharmacological interventions for DID include the use of prazosin in reducing nightmares, carbamazepine to reduce aggression, and naltrexone for amelioration of recurrent self-injurious behaviors.[17] See Table 3 for a description of pharmacological interventions for DID.

CONCLUSION

A wide variety of dissociative disorders including DID occur in the psychiatric population and may be misdiagnosed or underdiagnosed for a variety of reasons. Some psychiatrists believe these disorders are extremely rare and some believe that they do not exist. More research is needed, but these disorders may be more common than previously thought.

Psychotherapy is the cornerstone of a multidisciplinary treatment plan for dissociative disorders and other trauma-related disorders and must be incorporated into the interventional strategy; whether the mode of psychotherapy is supportive or psychodynamic in nature, or some combination of various approaches, the treatment must be based on the quality and acuity of the patient’s symptoms.

Researchers’ understanding of DD has been augmented by developments in investigative tools and strategies but also by a willingness of mainstream researchers to acknowledge the importance of traumatic dissociation in psychiatry and to investigate the possible effects and outcomes in patients who present for treatment.[19] Compared to other psychiatric disorders, DD are associated with severe symptoms, including frequent suicide attempts and self-injurious behavior, as well as a high utilization of mental health resources. As a result, DD exact a high economic as well as personal cost to patients and society. Research in the past five years indicates that DD patients show a poor response to standard trauma treatment and exhibit high levels of attrition from treatment. Much remains to be learned about the neurobiology, assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of DD and other trauma disorders.

References

1. Coons PM. The dissociative disorders: rarely considered and underdiagnosed. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998;21(3):637–648.

2. Moytano O, Claudon P, Colin V, et al. Study of dissociative disorders and depersonalization in a sample of young adult prench Population. Encephale. 2001;27(6):559–569.

3. Brand BL, Classen CC, McNary SW Zavari P. A review of dissociative disorders treatment studies. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2009;197(9):646–654.

4. Brand BL, Lanius R, Vermetten E, et al. Where are we going? An update an assessment, treatment, and neurobiological research in dissociative disorders as we move toward the DSM-5. J Trauma Dissociation. 2012;13(1):9–31.

5. Myrick AC, Brand BL, McNary SW, et al. An exploration of young adults’ progress in treatment for dissociative disorder. J Trauma Dissociation. 2012;13(5):582–595.

6. Allen JG, Smith WH. Diagnosing dissociative disorders. Bull Menninger Clin. 1993;57(3):328–343.

7. Spiegel D, Loewenstein RJ, Lewis-Fernandez R, et al. Dissociative disorders in DSM-5. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(9):824–852.

8. American Psychiatric Association. The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press Inc; 2000.

9. Gillig PM. Dissociative identity disorder: a controversial diagnosis. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6(3):24–29.

10. Putnam FW. Dissociation in Children and Adolescents: A Developmental Perspective. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1997.

11. American Psychiatric Association DSM-5: the future of psychiatric diagnosis. http://www.DSM5.org/ProposedRevision/Pages/proposedrevision.aspx Access date October 21, 2012.

12. Tamar-Gurol D, Sar V, Karadag F, Evren C, Karagoz M. Childhood emotional abuse, dissociation, and suicidality among patients with drug dependency in Turkey. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2008;62(5):540–547.

13. Somer E, Altus L, Ginzburg K. Dissociative psychopathology among opioid use disorder patients: exploring the “chemical dissociation” hypothesis. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(4):419–425.

14. Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman J. Psychiatry, Second Edition. Sussex, UK:?Wiley-Blackwell Press; 2003(1).

15. Gabbard, G. Long-term psychodynamic psychotherapy In: Levy R, Ablon SJ (eds). Handbook of Evidence-Based Psychodynamic Psychotherapy: Bridging the Gap between Science and Practice. (2004).

16. Downing R. Understanding integration. Sidran Institute Traumatic Stress Education and Advocacy 2003. http://www.sidran.org/sub.cfm?contentID=73§ionid=4. Access Date 01/27/13.

17. Sadock BJ, Sadock VA. Kaplan and Sadock’s Comprehensive Book of Psychiatry, Seventh Edition. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins; 2000.

18. Stern TA, Rosenbaum JF, Fava M, et al. Massachusetts General Hospital Comprehensive Clinical Psychiatry. Waltham MA: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008

19. Dalenberg C, Loewenstein R, Spiegel D, et al. Scientific study of the dissociative disorders. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76(6):400–401; author reply 401–403.