by Uzma Ilyas, PhD scholar, and Prof. Dr. Saima Dawood Khan,PhD

Ms. Ilyas is PhD Scholar, Centre for Clinical Psychology, University of the Punjab in Lahore, Pakistan, and Principal Lecturer, Psychology Department, University of Central Punjab in Lahore, Pakistan. Prof. Dr. Khan is Director, Centre for Clinical Psychology, University of the Punjab in Lahore, Pakistan.

Funding: No funding was provided for this study.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2023;20(7–9):30–36.

Abstract

Background: The purpose of the study was to explore social anxiety in adolescents as well as associated factors, such as parenting styles, self-esteem, quality of life, emotional intelligence, and brain activity, in social anxiety.

Methods: A systematic review of articles related to social anxiety in adolescents, associated factors, and brain activity from 2012 to 2022 was performed. Google Scholar, PubMed, and Science Direct were used as research gates to find the relevant articles.

Results: Ten articles were sorted among 50 articles according to inclusion criteria. The included studies were based in Pakistan, India, and China, which indicated similar results. Social anxiety was directly related to low self-esteem, authoritarian parenting style, interbrain synchrony between parents and adolescents, low quality of life, weak emotional intelligence, and higher activity in the amygdala of the brain.

Conclusion: Social anxiety is common in male-dominant (patriarchal) societies where authoritarian parenting is practiced, which leads to low self-esteem, weak emotional intelligence, and low quality of life in adolescents. Social anxiety is also associated with higher activity in the amygdala and lower gamma interbrain synchrony.

Keywords: Social anxiety, adolescence, quality of life, parenting style, self-esteem, amygdala, emotional processing, attention bias

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is a form of fear that is related to social situations in which there is a fear of being judged. According to the National Health Survey (NHS), SAD, also called social phobia, is a long-term and overwhelming fear of social situations.1 This fear is experienced by the individual while dealing with social situations. As this fear is experienced, the amygdala is activated. In one study, there was fundamentally more noteworthy action observed in the amygdala, rostral, dorsomedial and lateral frontal, and parietal cortices of the brain, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI).2

This systematic review focuses on social anxiety in adolescents in Pakistan, India, and China. A lifetime prevalence of social anxiety disorder of up to 12 percent has been reported in the United States (US), and one-year prevalence rates of 0.8 percent in Europe3 and 0.2 percent in China4 have been reported. Prevalence of social anxiety disorder in adolescents in India is 12.8 percent,5 whereas the prevalence of anxiety in adolescents in Pakistan is 22.5 percent.6 Social anxiety disorder is the second most common anxiety disorder, with a lifetime prevalence of 6.7 to 10.7 percent in Western countries.7

Social anxiety is associated with different factors, such as parenting style, self-esteem, quality of life, wellbeing, emotional intelligence, and emotions. It is also related to the brain’s orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) and its connection to the amygdala. Correlating social anxiety to emotions and emotional intelligence, it can be postulated that anxiety itself is an emotion that manifests as fear, whereas emotional intelligence deals with the management and understanding of one’s own emotions and their influence on oneself and others. Adolescence is a crucial period in which individuals identify their identity and engage with the world. Adolescents with social anxiety might struggle with emotional dysregulation, as well as emotional intelligence issues.

In the development of this psychopathology, the parenting styles can make children more vulnerable to mental health comorbidities and distress. Punitive, overcritical parenting was found to be associated with the predisposing and perpetuating factor of anxiety disorder. Family dynamics with highly expressed emotions and enmeshed boundaries also serve as a trigger for the onset of SAD and its relapse. An authoritarian parenting style due to inflexible child rearing practices has high concordance with development or early onset of psychopathology among children and adolescents.8 Features of an authoritarian parenting style include strict rules and punishments as a tool to discipline children during their developmental years. Whereas an authoritative parenting style includes many demands and a sense of control, at the same time, they also provide acceptance and are responsive toward the children.9 Features of a mindful parenting style include the sense of freedom, acceptance, and openness, which brings a positive attitude to parent-child relationships.10 Authoritarian parenting styles are mostly seen in male-dominant societies, such as India and Pakistan. The factors that affect social anxiety in children due to parenting can be caused by familial attitudes, including rejection, hostility, and emotional distancing, or they may be caused by modeling negative beliefs and thoughts, which creates the perception of the world as threatening and hostile and the predisposition to develop a negative attributional style. Similarly, interbrain synchrony between parent and child is the child’s first social interaction in the world. Thus, social anxiety is related to interbrain synchrony between the parent and the individual.

Self-esteem plays a vital role in the emotional development of an individual’s social interactions and maintenance of interpersonal relationships.11 Studies have depicted that low self-esteem leads to SAD.12 Low self-esteem instigated by authoritarian parenting leads to externalizing behaviors, aggressive, rebellion, low confidence, depression, and anxiety.13

Methods

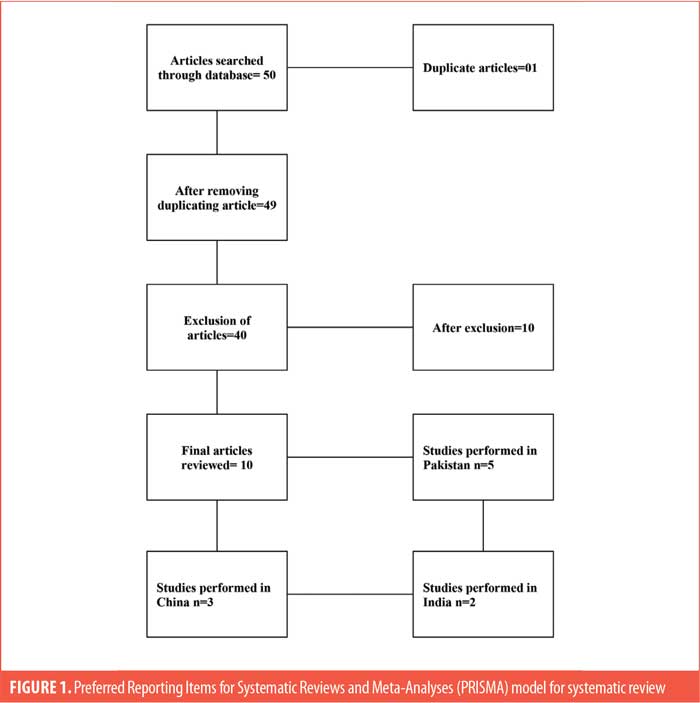

A comprehensive review was conducted as per methodology outlined by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. Articles published from 2012 to 2022 were included in the search. A pool of 50 articles was established. The process of scrutiny involved details about author, title, year, demographics, variables, sample, method, design, analysis, result, and references for the articles sorted for final stage.

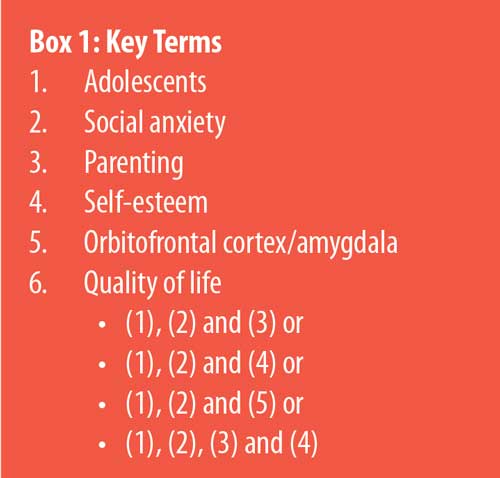

Literature search. Various search engines were used in this study. The dominant databases included Science Direct, Google Scholar, and PubMed. Search terms, such as “Pakistan,” “India,” and “China,” were also used. The pool of articles also contained articles from other countries. Key terms were “adolescence,” “social anxiety,” “amygdala,” “quality of life,” “parenting,” and “self-esteem” (Box 1).5

Inclusion and exclusion criteria. After filtering duplications, incomplete papers, and articles not published in the English language, 10 articles were found to have met the inclusion criteria. The pool of articles searched using Boolean operator through keywords (Box 1) were included for systematic review. The studies focused on three countries: Pakistan, China, and India. These articles were selected because the variables were interlinked.

The articles that did not meet inclusion criteria according to demographics and variables were excluded. Fifty articles that included populations from Australia, China, England, Japan, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, and the US were excluded.

Results

Fifty records were initially identified, based on titles. One study was duplicated, and 40 studies were removed, as they did not meet the criteria of age and population. As a result, 10 articles were extracted for the purpose of review. Five studies were conducted in Pakistan, three in China, and two in India. Table 1 summarizes the 10 included studies. Most of the studies were cross-sectional, while the rest were independent group or mixed designs. The studies were conducted on adolescents, but some tasks were performed by their parents as well. Below, themes from the studies are described.

Theme 1: social anxiety and parenting style. Parenting style plays an important role in the development of a child’s personality. Therefore, social anxiety and parenting styles show a significant relationship. Uninvolved and authoritarian parenting styles, rejection, and neglect lead to social anxiety and social withdrawal.24 Authoritarian parents who have an uninvolved and distant parenting style can make adolescents more prone to social anxiety. Strict and demanding behavior from parents can lead to the development of insecurities in adolescents and a loss of confidence that can lead to social withdrawal. Mindful parenting decreases the likelihood of social anxiety, and children experience self-acceptance, high self-esteem, and confidence as a result.22

Theme 2: social anxiety and neural activity. Social anxiety affects the activity of the OFC, as the OFC controls negative responses and reacts to negative stimuli. The functioning of the OFC is disrupted when the emotional state is negative, and there is hyperactivity. The amygdala is activated in fearful or stressful situations, such as when an individual experiences social anxiety.Studies using fMRI have shown that there is also a correlation between the gray matter volume (GMV) of the OFC and its functional connectivity with the amygdala in social anxiety.25

When there is exposure to the same stimuli, parent-adolescent dyads showed interbrain synchrony. As it is a neural mechanism, the same regions of the brain activate in dyads when there is social interaction. It also shows the emotional bonding of dyads biologically.26 Electroencephalogram (EEG) was performed on the dyads, and gamma waves were observed. Emotional stimulation resulted in gamma waves. There is bias by individuals in perceiving that has an association with emotional processing.27 As gamma waves are fastest and involved in information processing and cognitive functioning, there was less gamma interbrain synchronization in a dyad in the parietal and central regions of the brain when exposed to negative treatment as compared to the second group of dyads when exposed to positive conditions.28

Theme 3: social anxiety and self-esteem. There is a very strong relationship between social anxiety and self-esteem. Adolescents who have less self-esteem are more prone to social anxiety. They do not like social interactions. It makes them uncomfortable, and they lack confidence. On the other hand, adolescents with good self-esteem enjoy the company of others and social interactions. They have confidence in themselves.29,30

Theme 4: social anxiety and quality of life. Social anxiety negatively affects the quality of life. It persists into adulthood and might increase the chance of suicide.31 In puberty, adolescents undergo physiological changes. This is a crucial period, and there is higher risk of social anxiety for individuals this age range.32 There is functional deterioration, lack of close relationships, poor satisfaction, poor peer relationships, social withdrawal and below average academic performance.16,33 Students from the public sector manifest exacerbated social anxiety due lack of resources, including tutoring, mentoring, and less options for extracurricular activities and social engagements.34,35 Socioeconomic status is also a factor. Individuals with healthier self-esteem and emotional intelligence are found to manage social anxiety more efficiently.36

Theme 5: social anxiety and differences based on sex. Surprisingly, there are no significant differences based on sex seen in social anxiety in Pakistan, China, and India as compared to the West. Social anxiety is almost equivalent between sexes. The prevalence of social anxiety is not higher in female individuals, as they foster close relationships that serve them as a protective factor.31 However, issues with self-esteem among female individuals in Pakistan and India has a higher prevalence, resulting from challenges of equity, discrimination, and societal pressure. Higher expectations and responsibilities are assigned to traditionally female roles that can affect self-esteem. Poor self-esteem also interplays with social anxiety and can manifest itself in varied emotional and behavioral symptoms.37

Discussion

The study aimed to investigate the composite parenting behaviors (parenting styles and dimensions), poor quality of life, neurological functioning, and interbrain synchrony of the brain that contribute to SAD in adolescents. This review has also identified the relationships between emotional intelligence and self-esteem with social anxiety, resulting in isolation and detachment behaviors in adolescents, and determined how these traits contribute to SAD-related issues in India, Pakistan, and China.

Interpreting the findings of social anxiety to parenting style. Studies have shown that the impression of events as being beyond one’s control (cognitive bias), excessive parental control, or patterns of regulating children’s activities reduces children’s perception of mastery and control over their environment and may increase their risk for social anxiety.24

One of the findings of this review suggests that authoritative parents socialize their children through involvement in interpersonal relations and constrained democratic interactions that are built up and maintained over time. Through dynamic encouragement, children could be taught parent-child relationships based on reciprocated affection and logical thinking. This responsiveness and sensitivity of parents toward the needs of children can create reciprocal responsiveness in children’s familial inputs and aspirations. A high level of tenderness paired with a high level of discipline seems to shield adolescents from worries, anxieties, and withdrawal tendencies, while also promoting the growth of social, cognitive, and self-control abilities. The results suggest that authoritative parenting does not cause social withdrawal or social anxiety in adolescents, despite the fact that it is positively connected with social-emotional difficulties in them38 and authoritarian parenting is significantly correlated with high levels of SAD in adolescents.10

According to a retrospective study, people with social anxiety report their parents as being emotionally cold, rejecting, and overly protective. Having authoritarian parental constraints on a child’s ability to make decisions encourages an overly dependent relationship with parents; impedes the growth of independence, selfhood, and age-appropriate mastery abilities; and sustains emotions of powerlessness and insecurity both inside and outside the home.36 Additionally, in the current review, neglectful parenting is categorized as having a lack of empathy, care, and concern for a child’s emotions and needs, a failure to spend time with a child, a lack of monitoring, and lax regulations. This leads to a diminished sense of control and acquired helplessness in the child, resulting in a lack of self-confidence, social hesitation, anxiety, and a detached demeanor in adolescents.24 As a result, the findings of the review have shown that adolescents will be more vulnerable to depression, anxiety, and other psychological issues as a result of higher levels of negative parenting practices.39

Interpreting the findings of social anxiety to neural activity of the brain. Social anxiety typically starts during adolescence, a time of significant brain and mental state development. One of the review findings shows that among the parent-child dyad, the synchronization of interbrain depicts biobehavioral processes, which indicates that during social contact, neural and behavioural processes coordinate. It also suggests that the impact of social anxiety on adolescents’ brain development and behavior is poorly understood.22 According to the findings, the GMV of the OFC and the functional connectivity (FC) of the OFC with the amygdala are both positively correlated with social anxiety.40 The same finding suggests that the OFC is involved in regulating emotional reactions. People with SAD have increased OFC activation when confronted with stressful situations, compared to healthy individuals. This demonstrated that in order to control the fear response, adolescents with social anxiety disorder require greater engagement from the OFC. Similarly, the FC of the OFC with the amygdala is strongly related to social anxiety. In essence, social anxiety can be determined by an overactive fear-processing circuit response to threats or negative inputs. In accordance with the structural and functional findings, social anxiety is positively correlated with the GMV of the OFC and the FC of the OFC with the amygdala. This is consistent with the idea that people who have higher levels of social anxiety may experience more pressure, embarrassment, and frustration, and as a result, they may use the OFC more frequently to control the amygdala’s reaction to negative emotion.22

Research also revealed that adolescent anxiety levels and parental monitoring have an impact on the frequency and effectiveness of adolescent-parent interactions. In social situations, people give off social indications through their activities, facial expressions, and postures. They frequently and spontaneously synchronize their actions, feelings, bodily functions, and neurological activities with those of others when participating in these social interactions. The first instance of a child’s social interaction is supposed to occur when the child and parent’s biological rhythms and social cues synchronize in their brains. One of the most crucial aspects of brain development is the emergence of interbrain processes through the link between a caregiver and a child.31 An experimental study involving hyperscanning has established the interbrain synchrony, which was considered a sensitive marker of social-emotional interaction. In the study, the parent-adolescent dyads were exposed to picture processing stimuli. Greater gamma interbrain synchronization in parent-adolescent pairs was seen in the high social anxiety group at parietal regions than in the low social anxiety parent-adolescent pairs under favorable circumstances. The picture processing task did, however, exhibit stronger gamma interbrain synchronization in the low-social anxiety parent-adolescent pairs under adverse conditions, compared to the high social anxiety parent-adolescent pair. These findings offer neurobiological evidence that the anxiety level of the adolescent may have an impact on how the parent and adolescent experience various emotions during the same emotional episode.15

Interpreting the findings of social anxiety to self-esteem. Social psychologists are aware of how self-esteem might help in challenging social or performance situations. The results of the review revealed a substantial negative relationship between social anxiety and self-esteem.29 Low self-esteem causes people to focus excessively on criticism from others and be more sensitive to rejection, which raises their anxiety levels in social situations. Conversely, high self-esteem makes it easier for people to generate accurate explanations for how they were seen negatively by others during social interactions and makes them less prone to worry.30 Negative self-evaluation is a tendency of those with low self-esteem. In social situations, certain negative beliefs are promptly recalled from memory and activated, leading to an inaccurate interpretation of the event and intense social anxiety. In the case of adolescent girls, they were seen to be cautious of interacting with boys, especially those who were enrolled in different educational systems.29 Most Asian women are forbidden from interacting with men due to cultural and religious norms; as a result, they are shy, anxious, and lack confidence, which shows that sanctimonious principles and cultural prohibitions in Asia (particularly in Pakistani society) hinder the ability for female individuals to socialize, which might result in psychological issues as adults. Nevertheless, the findings of different studies included in this review show that there is no difference based on sex among adolescents in the relationship between social anxiety and self-esteem, indicating that both male and female individuals experience the same anxiety in social interactions and do not differ significantly in terms of self-esteem. Adolescent male individuals likewise struggle with interpersonal ties, but adolescent female individuals are more socially apprehensive.29

Interpreting the findings of social anxiety to quality of life. According to the findings, social anxiety levels are negatively correlated with subjective quality of life.27,43 People who are socially anxious perform lower on quality of life tests than their peers who are not socially anxious. This review was unable to determine whether social anxiety lowers the quality of life or whether low quality of life increases social anxiety. However, adolescents in public schools, compared to their peers in private schools, have a greater prevalence of social anxiety. This could be a result of the lower socioeconomic level of those who attend public school, which has been linked to social anxiety. Furthermore, there are few opportunities for one-on-one mentoring in government-run public schools because of the higher student-to-teacher ratio and high rates of teacher attrition, which disadvantages the students because receiving mentorship from an adult or older student is beneficial in reducing anxiety.14

Interpreting the findings of social anxiety to emotional intelligence. According to the results of many studies included in this review, adolescents with high levels of social anxiety exhibit deficiencies in emotional expression and have a higher level of negative emotional suppression than adolescents without such issues.41 Social anxiety is also linked to the lack of access to effective emotional regulation techniques and dysfunctional emotional control due to fear of receiving a harsh evaluation during interactions with others.42,44 Adolescents with high levels of self-focused attention and social anxiety are more likely to be aware of their emotional reactions. As a result, they experience underlying emotional awareness, which makes them feel more concerned and causes inhibitory responses that may hamper social relationships. It has been found that adolescents who have stronger emotional intelligence have better emotional regulation and are less likely to experience social anxiety. Moreover, emotional intelligence levels were observed to have an impact on social skills in both adolescent male and female individuals.41

Limitations. This review is subject to a number of restrictions. Primarily, it focuses on three countries in Asia (China, Pakistan, and India), with very little information regarding other Asian countries. Though the current review used all available data, representativeness and generalizability is limited. Readers should use judgment when extending our findings to adolescents from other countries or with diverse cultural backgrounds. Studies with larger samples from various cultures and countries should be the subject of further research.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this review, we conclude that the time of a person’s life during which the most changes take place is when they are adolescents; it is also the phase when the majority of the social anxiety symptoms develop. Additionally, authoritarian and neglectful parenting styles, low quality of life, dynamics of interbrain synchrony, and the FC of the OFC with the amygdala, along with other parameters, can increase the risk of social anxiety in adolescents. Also, social anxiety is negatively correlated with emotional intelligence. Adolescents with social anxiety also have difficulty interacting with others and have low self-esteem due to poor self-perception. It is recommended to create awareness in families that adolescents’ self-esteem can be maintained by adopting considerate parenting, which could help them avoid developing SAD. Moreover, parents and teachers should be educated on anxiety issues and encouraged to work together to prevent the development of social anxiety and mental illness in children. In order to help adolescents overcome their social anxiety, a school-based group therapy program is suggested. Adolescents participating in this program can receive exposure therapy and instructions about social skills. These initiatives are urgently needed since they assist adolescents in managing their stress and anxiety.

References

- Kehoe WA. Generalized anxiety disorder. In: Dong BJ, Elliott DP, eds. ACSAP 2017 Book 2 Neurologic/Psychiatric Care. American College of Clinical Pharmacy; 2017:7–27.

- Blair KS, Otero M, Teng C, et al. Learning from other people’s fear: amygdala-based social reference learning in social anxiety disorder. Psychol Med. 2016;46(14):2943–2953.

- Alonso J, Angermeyer MC, Bernert S, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2004;420:21–27.

- Shen Y-C, Zhang M-Y, Huang Y-Q, et al. Twelve-month prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in metropolitan China. Psychol Med. 2006; 36(2):257–267.

- Mehtalia K, Vankar GK. Social anxiety in adolescents. Indian J Psychiatry. 2004;46(3):221–227.

- Bano Z, Ahmed R, Riaz S. Social anxiety in adolescents: prevalance and morbidity. Pakistan Armed Forces Med J. 2019;69(5):1057–1060.

- Fehm L, Pelissolo A, Furmark T, Wittchen HU. Size and burden of social phobia in Europe. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15(4):453–462.

- Wood JJ, McLeod BD, Sigman M, et al. Parenting and childhood anxiety: theory, empirical findings and future directions. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2003;44(1):134–151.

- Darling N, Steinberg L. Parenting style as context: an integrative model. In: Laursen B, Zukauskiene R, eds. Interpersonal Development. Routledge; 2017;161–170.

- McLeod BD, Wood JJ, Weisz JR. Examining the association between parenting and childhood anxiety: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27(2):155–172.

- Eccles JS, Lord S, Midgley C. What are we doing to early adolescents? The impact of educational contexts on early adolescents. Am J Educ (Chic III). 1991;99(4):521–542.

- Wang Z, Chang W. Enhance self-esteem evaluation model for children’s social anxiety and loneliness. Aggress Violent Behav. 2021;101666.

- Konopka A, Rek-Owodziń K, Pełka-Wysiecka J, Samochowiec J. Parenting style in family and the risk of psychopathology. Adv Hygiene Exp Med. 2018;72:924–931.

- Inam A, Khalil H, Tahir WB, Abiodullah M. Relationship of emotional intelligence with social anxiety and social competence of adolescents. Nurture. 2014;8(1):20–29.

- Farooq SA, Muneeb A, Ajmal W, et al. Quality of life perceptions in school-going adolescents with social anxiety. J Child Dev Disord. 2017;3:2.

- Mishra PI, Kiran UV. Parenting style and social anxiety among adolescents. Int J Appl Home Sci. 2018;5(1):117–123.

- Sandhu GK, Sharma V. Social withdrawal and social anxiety in relation to stylistic parenting dimensions in the Indian cultural context. Res Psychol Behav Sci. 2015;3(3):51–59.

- Rana SA, Akhtar S, Tahir MA. Parenting styles and social anxiety among adolescents. New Horizons. 2013;7(2):21–34.

- Bano N, Ahmad ZR, Ali AZ. Relationship of self-esteem and social anxiety: a comparative study between male and female adolescents. Pakistan J Clin Psychol. 2012;11(2):15–23.

- Ahmad ZR, Bano N, Ahmad R, Khanam SJ. Social anxiety in adolescents: does self-esteem matter? Asian J Soc Sci Humanit. 2013;2(2):91–98.

- Chong-Wen W, Sha-Sha L, Xu E. Mediating effects of self-esteem on the relationship between mindful parenting and social anxiety level in Chinese adolescents. Medicine. 2022;101(49):e32103.

- Deng X, Chen X, Zhang L, et al. Adolescent social anxiety undermines adolescent-parent interbrain synchrony during emotional processing: a hyperscanning study. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2022;22(3):100329.

- Mao Y, Zuo XN, Ding C, Qiu J. OFC and its connectivity with amygdala as predictors for future social anxiety in adolescents. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2020;44:100804.

- Armsden GC, Greenberg MT. The inventory of parent and peer attachment: individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. J Youth Adolesc. 1987;16(5):427–454.

- Hahn A, Stein P, Windischberger C, Weissenbacher A, et al. Reduced resting-state functional connectivity between amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex in social anxiety disorder. Neuroimage. 2011;56(3):881–899.

- Schölvinck ML, Maier A, Ye FQ, et al. Neural basis of global resting-state fMRI activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107(22):10238–10243.

- Reindl V, Gerlo C, Scharke W, Konrad K. Brain-to-brain synchrony in parent-child dyads and the relationship with emotion regulation revealed by fNIRS based hyperscanning. Neuroimage. 2018;178:493–502.

- Gonzalez A, Zvolensky MJ, Parent J, et al. HIV symptom distress and anxiety sensitivity in relation to panic, social anxiety, and depression symptoms among HIV-positive adults. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2012;26(3):156–164.

- Hiller TS, Steffens MC, Ritter V, et al. On the context dependency of implicit self-esteem in social anxiety disorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2017;57:118–125.

- Pelham BW, Swann WB Jr. From self-conceptions to self worth: on the sources and structure of global self-esteem. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;57(4):672–680.

- Alkhathami S. Social anxiety and quality of life in adolescents: cognitive aspect, social interaction and cultural tendency. University of Bedfordshire; 2014.

- Jefferson JW. Social anxiety disorder: more than just a little shyness. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001 Feb;3(1):4–9.

- Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. The development of anxiety: the role of control in the early environment. Psychol Bull. 1998;124(1):3–21.

- Peng Z, Lam L, Jin J. Factors associated with social interaction anxiety among Chinese adolescents. East Asian Arch Psychiatry. 2011;21(4):135–141.

- Hidalgo R, Barnett S, Davidson J. Social anxiety disorder in review: two decades of progress. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2001;4(3):279–298.

- Kashdan TB, Herbert JD. Social anxiety disorder in childhood and adolescence: current status and future directions. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2001;4(1):37–61.

- Holas P, Kowalczyk M, Krejtz I, et al. The relationship between self-esteem and self-compassion in socially anxious. Curr Psychol. 2023;42(12):10271–10276.

- Federal Bureau of Statistics. 2001. Household income and expenditure survey. In: Siddiqui Z. Family functioning and psychological problems as risk factors in the development of juvenile delinquency. University of Karachi, Karachi-Pakistan; 2003.

- Laboviti B. Perceived parenting styles and their impact on depressive symptoms in adolescents 15–18 years old. J Educ Soc Res. 2015;5(1):171–176.

- LaBar KS, LeDoux JE. Partial disruption of fear conditioning in rats with unilateral amygdala damage: correspondence with unilateral temporal lobectomy in humans. Behav Neurosci. 1996;110(5):991–997.

- Cejudo J, Rodrigo-Ruiz D, López-Delgado ML, Losada L. Emotional intelligence and its relationship with levels of social anxiety and stress in adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;15(6):1073.

- Abasi I, Dolatshahi B, Farazmand S, et al. Emotion regulation in generalized anxiety and social anxiety: examining the distinct and shared use of emotion regulation strategies. Iranian J Psychiatry. 2018;13(3):160–167.

- Mbua P, Adigeb AP. Parenting styles and adolescents’ behaviour in central educational zone of cross river state. Eur Sci J. 2015;11(20):354–368.

- Ran G, Zhang Q, Huang H. Behavioral inhibition system and self-esteem as mediators between shyness and social anxiety. Psychiatry Res. 2018;270:568–573.