by Atmaram Yarlagadda, MD; Adrian R. Johnson, LCSW, MSW; Cheyenne M. Bickerstaff, BS; Joseph R. Yancey, MD, MBA; Samuel L. Preston, DO; Liquori L. Etheridge, LCSW; Michelle Maddalozzo, LCSW; Samuel Ochinang, LCSW; Rosemary A. Jackson, DNP, PMHNP-BC; and Anita H. Clayton, MD

Dr. Yarlagadda is Installation Director of Psychological Health at McDonald Army Health Center in Fort Eustis, Virginia. LTC Johnson currently serves as the Deputy Installation Director of Behavioral Health for the Desmond Doss Health Clinic in Schofield Barracks, Hawaii. Ms. Bickerstaff is a Behavioral Health Specialist at McDonald Army Health Center in Fort Eustis, Virginia. Dr. Yancey is Assistant Professor at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland. Dr. Preston is Associate Professor, Department of Psychiatry at Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences in Bethesda, Maryland, and is with the Office of the Army Surgeon General, Defense Health Headquarters in Falls Church, Virginia. Mr. Etheridge is with Garland School of Social Work, Baylor University in Waco, Texas. Dr. Maddalozzo is with the Langley Air Force Base Mental Health Clinic in Hampton, Virginia. Mr. Ochinang is Deputy Director for Psychological Health at McDonald Army Health Center in Fort Eustis, Virgnia. Dr. Jackson is with Fort Eustis Behavioral Health Clinic in Fort Eustis, Virginia. Dr. Clayton is with University of Virginia in Charlottesville, Virgnia.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: Dr. Clayton has received grants from Daré Bioscience; Janssen; Relmada Therapeutics, Inc.; and Sage Therapeutics; advisory board fee/consultant fees from Fabre-Kramer; Janssen Research & Development, LLC; MindCure; Ovoca Bio PLC; PureTech Health; S1 Biopharma; Sage Therapeutics; Takeda/Lundbeck; Vella Bioscience, Inc.; and WCG MedAvante-ProPhase; royalties/copyright from Ballantine Books/Random House; Changes in Sexual Functioning Questionnaire; Guilford Publications; and shares/restricted stock units from Euthymics; Mediflix LLC; and S1 Biopharma. All other authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2022;19(10–12):10–15.

Abstract

Objective: The goal was to promote early diagnosis and referral of patients with depressive symptomology in the primary care setting using a biopsychosocial-informed risk stratification tool to prevent suicides.

Methods: A qualitative analysis of military suicides stationed at Fort Eustis, Virginia, using demographics from Fatality Review Boards (FRBs) of 10 cases assessing shared biopsychosocial stressors was conducted. The case reviews were used to assess the failure modes and effects analyses (FMEA), prompting the development of a performance improvement (PI) plan via a risk stratification scale that recognizes opportunities for intervention in the primary care and supervisor/peer settings to improve patient outcomes.

Results: FMEA revealed the presence and interplay of multiple biopsychosocial stressors specifically impacting relationships, occupational functioning, financial status, legal issues, and undiagnosed mental health conditions across the 10 suicides reviewed. Furthermore, the severity of each stressor was best examined from a dimensional perspective to gauge the impact on or impairment of the individual in the military setting. The dimensional use of biopsychosocial stressors is congruent with our hypothesis that an increase in duration and intensity of biopsychosocial stressors increases risk of suicide.

Conclusion: This case series reveals a gap in suicide assessment and suggests the use of a dimensional approach to measure biopsychosocial stressors at the entry level, such as primary care settings, or in the case of the military, during routine counseling. Additionally, a risk stratification tool that crosses biopsychosocial domains could provide a more accurate assessment for self-harm, in turn enabling a timely referral to appropriate helping agencies, including nonclinical resources.

Keywords: Suicide, primary care, major depressive disorder, biopsychosocial, suicide risk factors, suicide risk assessment, military suicide, dimensional psychiatry, military medicine, self-harm

Individuals who complete suicide often do not have a documented psychiatric diagnosis. A relevant, commonly observed factor is a primary care visit within 30 days of the event, but not a behavioral health (BH) appointment.1 In one study, researchers searched PsychInfo for articles identifying suicide interventions in primary care. Throughout the literature, it was evident there were multiple factors (e.g., relationships, legal actions, financial stressors, occupational difficulties, undiagnosed mental health concerns) that contributed to suicide among service members (SMs), and many times, these SMs had not been involved in BH care. The literature supports the integration of interdisciplinary involvement and triaging of risk levels at all levels of care to decrease risk of suicide.1

This case series reviews 10 cases of completed suicides among army soldiers on the Fort Eustis military installation in 2020, using data collected from multiple Fatality Review Boards (FRBs), post-event engagements that outline the deficiencies in the form of failure modes and effects analyses (FMEA) of the existing process, leading to the implementation of performance improvement (PI) with better outcomes. Although the power of the current study is small, in the context of the given topic (i.e., completed suicides), it is relevant to conduct a FMEA review. The FRB allows all personnel involved with the incident to plan short- and long-term actions to support the installation and unit, allowing the best support for soldiers and survivors. Board members discuss required actions, exchange information, and furnish the Casualty Assistance Officer (CAO) with information to update the family. Several factors can be identified that contribute to the loss of life via suicide. Patterns emerge, and common features leading to completed suicides point to biopsychosocial stressors frequently overlooked during the screening process in the primary care setting prior to death. The biological element of passive suicidal thoughts exacerbated by acute and chronic psychosocial stressors can trigger an acute depressive episode with fatal outcomes.2–5

This case series reviews and analyzes 10 cases of suicide by SMs to highlight the significance of psychosocial stressors in the absence of past established mental health history. The goal of this analysis is the development of a scale to measure psychosocial stressors in the context of passive suicidal ideations to mitigate the risk of suicide, grounded in a dimensional (patient-reported characterization of symptom severity), rather than categorical (determination of presence or absence of a condition per an established threshold), perspective, addressing imminent threat of self-harm.

Methods

Review of case reports. Cases of 10 male active-duty SMs were reviewed in this study. Data for this review was gathered through military medical records, line of duty investigations, and, most significantly, FRBs facilitated by unit commanders involving multiple agency representatives and experts in personnel, religious affairs, emergency services, housing, public affairs, suicide prevention, behavioral health, and others as needed. The FRB process presents military demographic data (e.g., training, time in service, specialty, deployments, etc.), discusses Criminal Investigation Division police reports, and highlights firsthand recent accounts of interactions with peers, supervisors, and family members for the team to gain a holistic perspective of the deceased. The purpose of the FRB is to identify gaps in risk identification and mitigation and to implement appropriate countermeasures through training and policy. Results of FRBs are widely distributed horizontally and vertically among military units.

The demographics of the 10 individuals who completed suicide reflect a mixed population. All 10 were male active-duty SMs. Eight of the 10 were Caucasian/White, one was African American/Black, and one was Hispanic. Eight of the 10 were between the ages of 18 and 24 years, and the remaining two were over the age of 40 years. The average age was 25.3 years. The marital status of the SMs was as follows: five married (of the five, two were pending divorce, with one additionally discussing divorce), one legally separated, and four single (though three were in a known relationship). Seven of the 10 were junior enlisted (E-1 to E-4); two were noncommissioned officers (E-5 and E-6); and one was a Warrant Officer (CW3). Nine of the 10 had low socioeconomic status, and eight had served five years or less in military service. Additionally, all SMs were assigned to units residing in Fort Eustis, Virginia, and died in 2020.

A review of the 10 cases revealed many similarities in five areas categorized as psychosocial stressors. According to Pruitt et al,6,7 common risk factors associated with death by suicide include a failed relationship, problems at work, pending legal and/or military charges, financial concerns, and presence of a mental health disorder.

A search of PsycInfo was conducted to identify studies that focus on the correlation between major depressive disorder (MDD), suicide, and dimensional psychiatry for triaging in primary care settings. Search terms included “primary care,” “mental health,” “suicide,” and factors leading to suicide, including “relationships,” “occupational functioning,” “financial stressors,” “legal problems,” “undiagnosed mental health conditions,” and “involvement in the military.” To provide a more in-depth analysis, we examined active service duty members from United States (US) forces from the years 1999 to 2021. Peer-reviewed articles were also included in the search. Exclusionary criteria included anything that did not meet inclusion criteria and articles concerning veterans.

Risk stratification/development of scale and standard operating procedures. Expanding risk stratification to include evaluation of psychosocial stressors in the context of Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) scores and rating of the acuity of depression (biological factors) may identify SMs at risk of suicide. Measuring psychosocial risk factors and MDD acuity in the form of an algorithm, therefore, becomes extremely important, especially in young male individuals who are competitive and ambitious, and individuals genetically classified as rapid metabolizers of medications. We propose a scale that will be inclusive from a multidisciplinary standpoint, starting with BH (history of mental health problems) and including relationship troubles through the Family Advocacy Program and addictions with Substance Use Disorder Clinical Care (SUDCC), in addition to other psychosocial factors (e.g., legal and financial problems). The rationale behind the multidisciplinary model is the effort to proactively track and refer those who have not been formally registered or identified as at risk under any single multidisciplinary section above to receive BH in an effort to better anticipate and prevent poor or lethal outcomes. Once an individual is recognized as needing multidisciplinary intervention, the risk level would automatically be raised to high, with patients monitored closely/weekly.

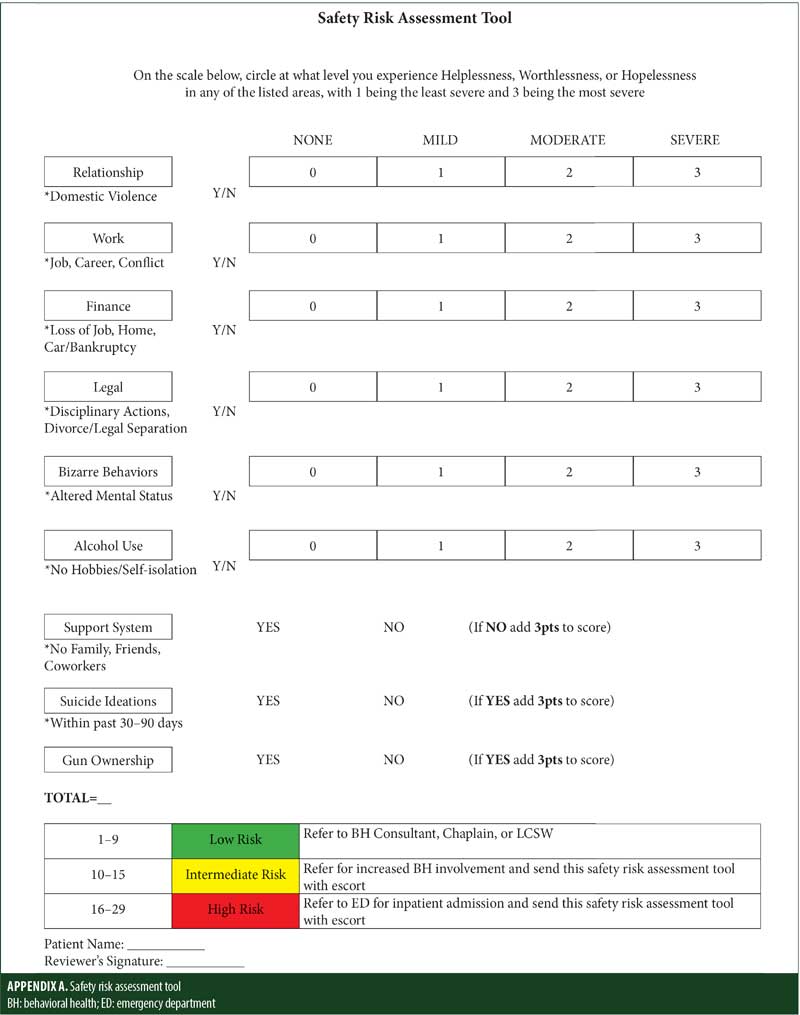

With the Commanders Service Member Safety Risk Assessment scale (Appendix A), evaluators can assess the level of hopelessness, helplessness, or worthlessness in seven categories, with scores ranging from 0 (none) to 3 (severe). The SM is assessed in terms of severity of need/presenting problem; additionally, risk factors of support system, suicidal ideations, and gun ownership are evaluated. This screener may be administered at in-processing or by the BH consultant in the primary care provider (PCP) office. Overall score determines if the SM is at low risk (0–9), intermediate risk (10–14), or high risk (16–21).

The five major categories of the scale are:

- Relationships: This can include family or intimate relationship stressors. Examples would be domestic abuse or the ending of a relationship.

- Work: Examples of stressors in this area would be struggles with career progression, level of responsibility of the SM, or conflicts with peers.

- Finance: Examples of stressors in this area are pay, overwhelming amounts of debt, bankruptcy, and potential loss of job.

- Legal: Examples of stressors in this area are legal action, to include punishment under the Uniform Code of Military Justice (UCMJ), disciplinary actions within the unit, or civilian court (criminal or civil).

- Undiagnosed mental history or bizarre behaviors, to include:

a) Developmental disorders, such as Asperger’s syndrome and autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Additionally, this category encompasses adverse childhood experiences, which is best described as any trauma that the SM experienced growing up, including an abusive family, neglect, poverty, and sexual trauma.

b) Alcohol use: It is important to know whether an SM is taking care of their health and making lifestyle choices that promote healthy coping skills and stress relief. If the SM is no longer engaging in their hobbies, has stopped exercising, and is self-isolating with alcohol use, that puts them at a higher risk for self-harm.

c) Support system: This includes family, friends, or co-workers that an SM can turn to in a time of need or crisis who can help motivate the SM to seek appropriate care.

d) Suicidal ideation: An SM’s expression of current suicidal ideation and acknowledgment of possession of a gun automatically applies five points to the final score, and they should be taken to the nearest emergency room (ER) for evaluation and assessment for admission.

The scale (Appendix A) has recommended appropriate referrals based on the risk level and the need for care.

Recognizing opportunities for intervention. In the current article, on a continuum, for the identified primary risk factor (e.g., poor relationship at the time of suicide), the risk escalation appears to be consistent in all 10 cases. Primary care visits, as opposed to BH visits, are more common during this period,1 and this was the case with most of the 10 cases. Breakdown of scores on the scale can provide guidance on the disposition for level of care indicated/mandated in any given case. Diagnostic criteria and specifiers for mild, moderate, and severe MDD are frequently missed and can be correlated with scores on the scale.

Early diagnostic considerations for MDD can be related to feelings of helplessness for scores between 0 to 9, indicating mild or low risk; feelings of worthlessness for scores between 10 to 15, indicating moderate risk; and feelings of hopelessness for scores between 16 to 29, indicating high risk. Our scale suggests referral recommendations based on the risk level and need for care and must be individualized and patient-centered.

Reporting of high-risk criteria and recommendations. It is recommended that the command administer the screening tool (Appendix A), especially when SMs are placed on a high-risk list by commanders and have had no BH points of contact. These high-risk lists from commanders are maintained separately from the high-risk lists that are developed by BH teams. Therefore, while the command might be aware of concerns related to the SM, the BH team might not be, and the SM is not provided with any clinical interventions. Command administration of the screening tool would highlight areas of concern related to the SM and could be a key tool for early unit-based intervention and proactive measures. Early interventions could include treatment options offered by medical officers/teams within the unit, which might potentially prevent suicides by decreasing risk.

Relevance of biopsychosocial risk factors. C-SSRS scores have not been shown to be the gold standard as far as death by suicide is concerned and are not inclusive of information that can be derived from the biopsychosocial model.8 According to Giddens et al,8 the C-SSRS does not encompass nor account for risk factors associated with suicidal behaviors or ideations. Rather, it only measures suicidal thoughts or behaviors. The biological element of acute MDD seems to be most apparent in all 10 of these cases. It is important to note that MDD can intensify the likelihood that one will attempt self-harm.9 Bolton et al10 found that MDD is directly correlated with suicide attempts, suggesting an increased risk for suicidal behaviors. Yet, with an understanding of these risk factors for suicide, PCPs might be sensitive to the need for heightened attention to assessments for a major depressive episode. Additionally, in the setting of acute MDD, identification of severe psychosocial stressors can prevent lethal consequences. This supports the poor relevance of C-SSRS scores in patients who have completed suicides, as the scores do not reflect acuity of depression reflected by worsening vegetative symptoms, such as helplessness, hopelessness, and worthlessness, at a given moment.

Results

Relationships. In the current articles, nine of the 10 cases of completed suicide suffered from some type of relationship stressor, ranging from a recent break-up, possible separation from spouse due to relationship discord, or pending divorce. Of note, one suicide occurred one day after a discussion of divorce with a spouse, another occurred after a recent legal separation, and a third occurred within a week following a break-up with their significant other. Only one of the 10 SMs was reported to not be/have been in a relationship preceding death.

Occupational functioning. All the cases reviewed reflected some occupational stressor that had direct career implications. Occupational stressors identified included difficulty with duty performance, peer or supervisor relationship stress, a perception of burdensomeness with respect to accomplishment of unit mission objectives, and lack of connection to others in the workplace. Due to the accountable nature of the military setting, unit commanders are responsible for the health and well-being of an SM during both on- and off-duty hours. This implies that some occupational stressors could have legal repercussions and thus overlap with legal problems discussed below.

Financial stressors. Financial stress was another common factor among the 10 cases reviewed. Factors related to financial stress included shame associated with not being able to provide for the family, perceived failure as head of the household, and feelings of burdensomeness to family, friends, or society.11,12 Nine of the 10 cases involved SMs from a lower socioeconomic class. Five of the 10 cases had financial difficulties in which the individual expressed immediate difficulty supporting himself or his family, despite salaried income and basic allowances. Two cases involved divorce with the payment of alimony, and one involved both alimony and child support. One case involved an SM providing for two geographically separate households on a single income.

Legal problems. According to Ghahramanlou-Holloway et al,13 legal stressors are also a risk factor for self-harm or suicidal behavior in the military population. Eight of the 10 cases involved legal issues. Two stemmed from legal separation from a spouse or divorce, two had been accused of sexual assault, two were facing administrative separation, one involved sibling custody, and one was under investigation for falsifying official government documents. The FRB investigation found that the individual who falsified official documents did so to assist in obtaining a swift divorce to alleviate the increasing relationship and financial distress the divorce was causing. The actions of this individual were discovered, and he was subsequently put under investigation, with the likely outcome of administrative punishment under the UCMJ. Furthermore, punishment under the UCMJ would have jeopardized retirement benefits for this individual.

Undiagnosed mental health history. Only three of the 10 SMs had an appointment with a BH provider within six months of death. Medical records of individuals with BH involvement indicated a degree of symptom stability. None had a significant diagnosis that required inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. Case review indicated that four of the 10 individuals had a history of suicidality (from past attempts to past ideation) expressed to others (including family and friends, but not medical professionals). Moreover, six SMs had a medical encounter with their primary care manager within 60 days of death and were not treated for depressive symptoms.

Discussion

As evidenced by the review, it is probable that relationship stressors could be a catalyst for death by suicide among SMs. The literature supports this view, as Hyman et al14 reported that divorce and/or separation from a spouse or partner placed an SM at higher risk for self-harm and/or a suicide attempt. Additionally, Landes et al15 found that of all evaluated risk factors, relationship problems are of particular importance for suicide, while any co-occurring mental disorders can further increase the risk in an SM.

Occupational stressors in the military environment can impact one’s well-being, whereas factors that might reduce suicide risk for an SM include trustworthiness, connection, concern for overall success, and morale of the individual, as well as unit cohesion and support.16–18

A dimensional approach considering biopsychosocial metrics, as opposed to categorical methodology (i.e., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition [DSM-5] criteria), places the acuity or imminent threat to self as the defining criteria for hospitalizations. This approach has advantages in prioritizing safety and stabilization of depressive symptom severity. Raising the risk stratification methodology by including interdisciplinary involvement, (e.g., psychiatry, psychology, family advocacy, SUDCC, and legal) in a high-risk treatment paradigm invites a dimensional approach to address dimensional factors. Although it is premature to comment on conclusions of better outcomes, as measured by a decrease in the number of suicides since 2020 (2 suicides in 2021 and 0 suicides in 2022) at one military installation, results from preliminary observation seem promising as policies developed from the FRB garnered a multi-disciplinary approach from community agencies and military units (information on file with author). Development of our tool allows for appropriate triaging at any level, be it primary care, family health, internal medicine, family advocacy, SUDCC, unit commanders, chaplains, or educational and training facilities. Conversion to an electronic format will further these goals. Although privacy and confidentiality are of concern, safety and saving lives must remain the priority, and safety should be assessed frequently at every level. We hope this tool provides that opportunity for patients and the multidisciplinary team.

Legal actions adversely impact an SMs career, which, in turn, negatively affects their overall health, in that the mental strain that comes from legal stressors can exacerbate other symptoms and degrade health and fitness of SMs.

LeardMann et al19 found there is a direct correlation between mental health problems and risk for suicide. Seven of the 10 SMs who committed suicide had no mental/BH points of contact prior to their death. Though they did not have contact with mental health providers, the majority had seen a PCP within one month of their suicide. Therefore, even if the individual has not seen a mental health provider, the PCP has the opportunity to provide a screening for mental and substance use disorders. A thorough evaluation by the PCP might offer the best possibility for lessening one’s overall suicide risk.19

Limitations. A limitation of this case series is that it focused on active-duty SMs, not the general population. Another limitation to the current case series is that it is unknown if the MDD diagnoses pre-existed the acute crisis periods that led to the death by suicide.

Conclusion

FMEA based on the FRB results from completed suicides have consistently revealed the lack of engagement in properly assessing the biopsychosocial stressors described above. Risk stratification conclusions derived under the categories above from entry level screenings become critical. The safety risk assessment tool takes a dimensional approach aimed at screening and early triage of vulnerable individuals to the appropriate level of care might help prevent tragic outcomes.

References

- Dueweke AR, Bridges AJ. Suicide interventions in primary care: a selective review of the evidence. Fam Syst Health. 2018;36(3):289.

- Sainsbury P. The epidemiology of suicide. Roy A, ed. In: Suicide. Williams & Wilkins; 1986:17–40.

- Heikkinen ME, Aro HM, Henriksson MM, et al. Differences in recent life events between alcoholic and depressive nonalcoholic suicides. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18(5):1143–1149.

- Gould MS, Fisher P, Parides M, et al. Psychosocial risk factors of child and adolescent completed suicide. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996;53(12):1155–1162.

- Foster T, Gillespie K, McLelland R, Patterson C. Risk factors for suicide independent of DSM–III–R Axis I disorder: case–control psychological autopsy study in Northern Ireland. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175(2):175–179.

- Pruitt LD, Smolenski DJ, Bush NE, et al. Suicide in the military: understanding rates and risk factors across the United States’ armed forces. Mil Med. 2019;184(Suppl 1):432–437.

- Pruitt LD, Smolenski DJ, Tucker J, et al. Department of defense suicide event report (DoDSER) calendar year 2017 annual report. Department of Defense. 12 Jul 2018. https://www.dspo.mil/Portals/113/Documents/2017-DODSER-Annual-Report.pdf?ver=2019-07-19-110951-577. Accessed 1 Nov 2021.

- Giddens JM, Sheehan KH, Sheehan DV. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C–SSRS): has the “gold standard” become a liability? Innov Clin Neurosci. 2014;11(9–10):66–80.

- Kessler RC, Borges G, Walters EE. Prevalence of and risk factors for lifetime suicide attempts in the national comorbidity survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(1):617–626.

- Bolton JM, Pagura J, Enns MW, et al. A population-based longitudinal study of risk factors for suicide attempts in major depressive disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(13):817–826.

- Joiner TE, Van Orden KA, Witte TK, et al. Main predictions of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicidal behavior: empirical tests in two samples of young adults. J Abnorm Psychol. 2009;118(3):634–646.

- Richardson T, Elliott P, Roberts R. The relationship between personal unsecured debt and mental and physical health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(8):1148–1162.

- Ghahramanlou-Holloway M, Baer MM, Neely LL, et al. Suicide prevention in the United States military. In: Bowles S, Bartone P, eds. Handbook of Military Psychology. Springer; 2017:73–87.

- Hyman J, Ireland R, Frost L, Cottrell L. Suicide incidence and risk factors in an active duty US military population. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(S1):138–146.

- Landes SD, Wilmoth JM, London AS, Landes AT. Risk factors explaining military deaths from suicide, 2008–2017: a latent class analysis. Armed Forces Soc. 2021.

- Mitchell MM, Gallaway MS, Millikan A, Bell MR. Combat stressors predicting perceived stress among previously deployed soldiers. Mil Psychol. 2011;23(1):573–586.

- Pflanz SE, Ogle AD. Job stress, depression, work performance, and perceptions of supervisors in military personnel. Mil Med. 2006;171(1):861–865.

- Redman T, Dietz G, Snape E, van der Borg W. Multiple constituencies of trust: a study of the Oman military. Int J Hum Resource Manage. 2011;22(1):2384–2402.

- LeardMann CA, Powell TM, Smith TC, et al. Risk factors associated with suicide in current and former US military personnel. JAMA. 2013;310(5):496–506.