by Raymond Kotwicki, MD, and Philip D. Harvey, PhD

by Raymond Kotwicki, MD, and Philip D. Harvey, PhD

Dr. Kotwicki is with Skyland Trail and Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia; and Dr. Harvey is with the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, Miami, Florida.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10(5–6):14–19

Funding: This research was funded by Skyland Trail.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Kotwicki is the Medical Director of Skyland Trail. He reports no other conflicts of interest. Dr. Harvey is a member of the National Advisory board of Skyland Trail and is compensated for this service.

Key words: Bipolar disorder, psychosis, structured diagnoses, validity

Abstract: Background. Psychiatric diagnoses are important for treatment planning. There are a number of current challenges in the area of psychiatric diagnosis with important treatment implications. In this study, we examined the differential usefulness of two semi-structured interviews of differing length compared to clinical diagnoses for generation of diagnoses that did not require modification over the course of treatment.

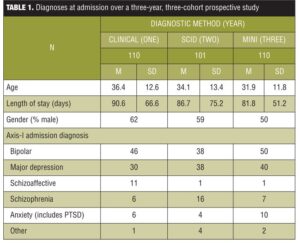

Methods. We performed a three-year, three-cohort study at an outpatient psychiatric rehabilitation facility, comparing the stability of admission diagnoses when generated by unstructured procedures relying on referring clinician diagnosis, the SCID, and the MINI. We examined changes in diagnoses from admission to discharge (averaging 13 weeks) and, during the second two years, convergence between referring clinician diagnoses and those generated by structured interviews. The same three interviewers examined all patients in all three phases of the study.

Results. Admission and discharge diagnoses were available for 313 cases. Diagnoses generated with the unstructured procedure were changed by discharge 74 percent of the time, compared to four percent for SCID diagnoses and 11 percent for MINI diagnoses. Referring clinician diagnoses were disconfirmed in Years 2 and 3 in 56 percent of SCID cases and 44 percent of MINI cases. The distinctions between unipolar and bipolar disorders were particular points of disagreement, with similar rates of under and over-diagnosis of bipolar disorder. The rate of confirmation of referring clinician diagnoses of schizoaffective disorder was 10 percent with the SCID and 11 percent with the MINI.

Discussion. In this setting, there appears to be a reasonable trade-off between brevity and accuracy through the use of the MINI compared to the SCID, with substantial improvements in stability of diagnoses compared to clinician diagnoses. Clinical diagnoses were minimally overlapping with the results of structured diagnoses, suggesting that structured assessment, particularly early in the illness or in short term treatment settings, may improve treatment planning.

Introduction

The reliability of psychiatric diagnoses has improved markedly since the introduction of structured psychiatric interviews.[1] These interviews were first developed in the late 1960s[2] and were fine tuned[3] up through the time of the introduction of the the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition (DSM-III)[4] in 1980. At the same time, the use of these structured interviews is still not common in everyday clinical practice, with most use in research settings. It is not clear how much the application of such interviews would impact the reliability and validity of diagnoses in clinical practice settings, but it seems likely that there are certain circumstances where the increase in validity would be quite substantial. The importance of collection of valid assessment data through structured assessment procedures is compounded by the problems in self-report seen in multiple psychiatric conditions;[5–7] questionnaire or checklist methods that do not contain interaction and observation with an interviewer are clearly subject to these concerns.

While we have recently shown in a literature review[8] that established schizophrenia can be diagnosed by clinicians with high degrees of concordance with the results of structured psychiatric interviews, there are still multiple diagnostic challenges. Patients with multiple, early-course conditions, even schizophrenia, often have diagnoses that change even when initially generated with structured procedures.[9,10] Psychiatric interviews vary in their focus (Axis-I vs. Axis-II), in their length, and in their assessment of the patient alone versus symptoms in their relatives. Structured interviews can require substantial time commitments and can require considerable training in order to be accurately employed.

Secular trends and patient expectations may also impact presumed diagnoses when new patients present for treatment in community mental health settings. Some of this variation may be due to exposure of potential patients to media or internet information, which may shape their opinions of their diagnoses. Bipolar disorder, for instance, has seen a marked increase in terms of its diagnosed prevalence in the last 20 years, after 40 years of stability in diagnostic prevalence,[11] with this increase corresponding with multiple, newly indicated treatments and associated advertising. In addition, an increased appreciation of the fact that bipolar disorders can be marked by brief episodes of hypomania rather than full manic episodes has increased the challenge in discrimination between bipolar and unipolar mood disorders. We know that distinguishing unipolar depression and bipolar illness has socioeconomic and functional implications.[12] Correspondingly, contemporary diagnostic trends may also incorrectly shape referring diagnoses when patients initially present for treatment. For instance, in previous years the concept of schizophrenia was expanded to include a variety of conditions outside the current boundaries, such as “pseudo-neurotic schizophrenia;”[13] there is a controversy about whether current concepts of mood spectrum conditions are overly broad as well.

There are several benefits of systematic collection of diagnostic data in everyday practice. There are suggestions that certain conditions, such as bipolar disorder, are both over-diagnosed[14,15] and frequently missed[16,17] in clinical settings. The most frequent suggestion to remedy this situation is a structured psychiatric interview. In fact, in the Pogge et al[14] and Zimmerman et al[15] studies, using a structured interview revealed over-diagnosis of bipolar disorder in adolescent and adults found to have major depression. Presumptive diagnoses of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are often generated on the basis of trauma exposure, without a systematic assessment of the other required symptoms.[18] Schizoaffective disorder is commonly diagnosed in clinical practice,[19] but the diagnosis has been argued to lack reliability20 and intrinsic clinical validity.[21]

Managed care companies are often interested in matching treatments to diagnoses and may refuse to reimburse for treatments that are not approved for specific indications, suggesting that in order to offer suitable treatments to patients accurate diagnosis is important. This is particularly relevant to time-limited treatment. As interventions such as day treatment or other rehabilitation therapies may be approved by insurance payers for delivery only for finite periods, inaccurate targeting of treatment interventions early on could lead to therapeutic interventions being applied for relatively abbreviated and potentially inefficacious periods. Thus, early identification of the eventual diagnosis can lead to enhanced ability to deliver appropriate treatments for a larger proportion of the time allowed. In this context, stability of diagnoses over time reflects an important component of the validity of these diagnoses while it is admittedly not the only important aspect.

This paper presents the results of a systematic study of the usefulness of structured psychiatric interviews. In a three-year, three-cohort, consecutive-admission study, we examined psychiatric diagnoses that were generated through unstructured clinical interviews and reliance on referral source diagnoses (Year 1), and two different psychiatric interviews that varied in their length of administration (Years 2 and 3). This study was performed at an outpatient psychiatric rehabilitation center that largely focuses on early course patients (mean age=24) and included three years of consecutive admissions from similar referral sources, where the assessment procedure was systematically changed at one-year periods with the same admission staff in place across the three years. We used the Structured Clinical Interview for the DSM (SCID)[22] for the second year of the study and the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)[23] for the third. Stability of diagnoses was indexed through the number of changes in diagnosis suggested by the clinical staff during the course of the patient’s treatment based on real-time observations and the results of the therapeutic process. For cases in Years 2 and 3, we also compared the referral source diagnosis for the patients to the diagnosis generated with a structured psychiatric interview.

Our hypothesis was that both of the structured interviews would be superior for generating stable diagnoses to both clinical judgments and referral diagnoses based on unstructured clinical observation. We were particularly interested in whether the considerably more abbreviated MINI would yield the same diagnostic stability, compared to the lengthier SCID, in these patients.

Methods

Participants. Research participants consisted of three years of consecutive admissions to a private, nonprofit, psychiatric rehabilitation facility. All admissions were examined; cases who were screened for admission but who did not receive services were not analyzed. All data were archived in a database and examined anonymously.

Patients signed a general consent form for their data to be examined anonymously and the Emory University Internal Review Board approved this study with expedited review and did not require signed informed consent for the analyses performed in this study. Patients with a primary diagnosis of a substance use disorder or personality disorders were excluded from admission due to regulatory issues during this time period. Dual-diagnoses patients as well as patients who had concomitant (but not primary) personality disorders were included in analyses.

The same three experienced, master-level, admission staff members participated over all three years. At the beginning of the study, these staff members had a minimum of three years of experience and an average of 5.

Cases were distributed sequentially across the three raters after referral to the treatment facility. These staff members were not involved in the treatment of the patients and did not have input into any subsequent treatment decisions. Further, the clinical staff members treating the patients were not informed of the plans to evaluate diagnostic stability as an outcome measure in the study. The reporting of the diagnoses consisted of the axis I and axis II diagnostic impressions which were entered into the electronic medical records. For this study, we focused on axis I diagnoses, as they were primary. Demographic data, including admission diagnoses, are presented in Table 1. As can be seen in the table, the ages of the cases declined slightly each year and there was a slight shift in the diagnostic distribution.

Procedure. The same three admission staff members participated in all three years of this study, which started October 1, 2008. In year one, all referrals for admission to the treatment center received a clinical diagnosis based on an interview at admission and information provided by the referral source. Throughout that year, the presumed “working diagnosis” was the referral diagnosis accompanied by an unstructured interview that occurred within 48 hours of the patients’ admission. In a pre-planned study, the three staff members were trained by an experienced psychiatric diagnostician. During Year 2, these same staff members, after training, interviewed all candidates for admission with the SCID. Interview training consisted of observed interviews, joint ratings, and consensus discussion of a series of cases not included in these analyses. After one year of use of the SCID, a third year of admissions were all interviewed and diagnosed with the MINI interview using identical training procedures.