by Tammie Lee Demler, BS, PharmD, MBA, BCGP, BCPP, and Charisse Chehovich, PharmD

by Tammie Lee Demler, BS, PharmD, MBA, BCGP, BCPP, and Charisse Chehovich, PharmD

Drs. Demler and Chehovich are with the Buffalo Psychiatric Center, New York State Office of Mental Health, and the University at Buffalo School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. Dr. Demler is also with the University at Buffalo School of Medicine, Department of Psychiatry.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this study.

DISCLOSURES: The author has no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: The review of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) is a safety mandate required by numerous organizations in the medication safety community. For adverse reactions to be properly reviewed, they must first be reported as potential events. There are notable challenges to ensure adequate and accurate reporting of ADRs that could be overcome if obstacles were better understood and addressed in a manner that is not punitive or threatening. Even reports of seemingly benign side effects might be valuable when considering the deleterious impact on medication adherence, notably in a psychiatric population. Our study examines the potential underreporting of adverse drug reactions that have been likely dismissed as expected side effects of medications. We underscore that there is a significant difference in what has been reported formally as an ADR and what should be reported based on the ability to identify prescribing changes that might be initiated in response to an ADR.

Keywords: Adverse drug event (ADE), adverse drug reaction (ADR), medication discontinuations, medication safety

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2021;18(7–9):29-38

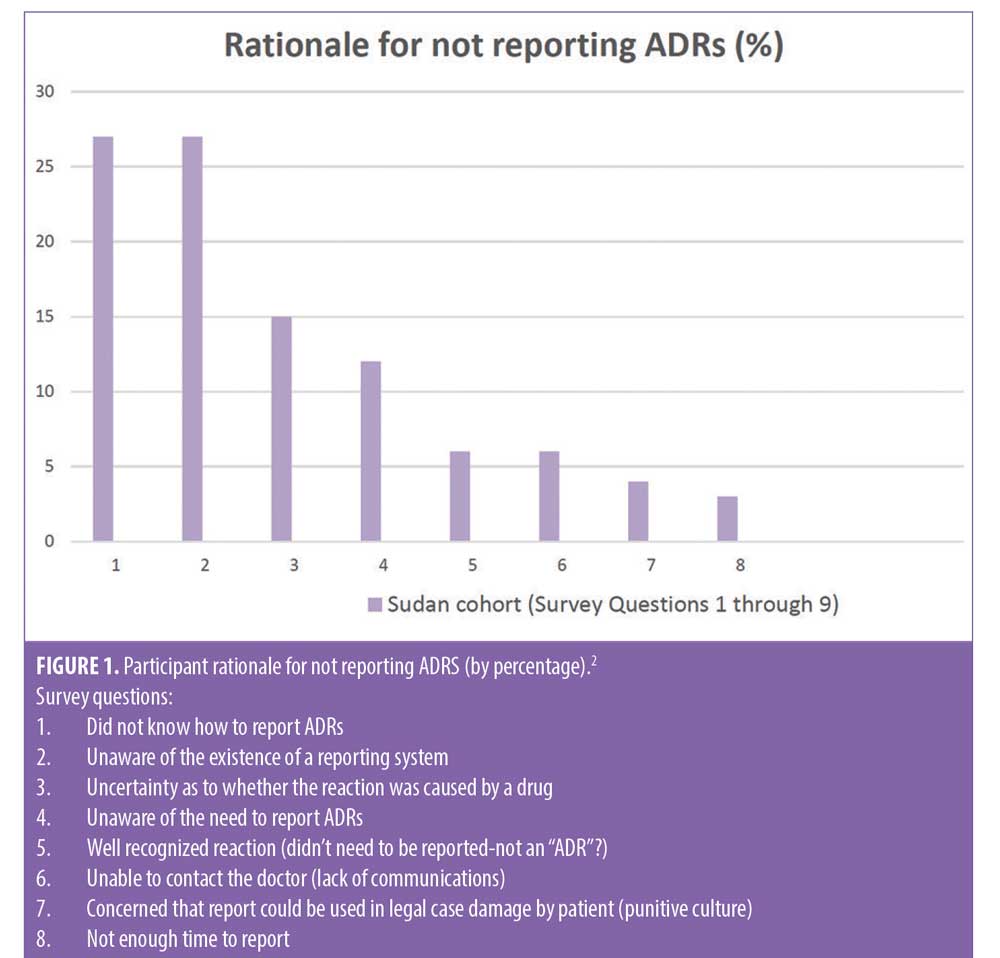

The safety of patients and the quality of care they receive is a goal that all health care organizations should be continually monitoring and setting future goals based on current benchmarks established during surveillance. Accreditation organizations, such as The Joint Commission (TJC), have promoted their mission as being centered around these core values and thus have developed standards that ensure that organizational leaders have implemented policies and procedures that align with this philosophy. In addition to assisting healthcare organizations develop methods to advance the skills, knowledge, and overall competence of those involved in the care and safety of patients, TJC also encourages the use of proactive methods to increase accountability that also reduce the fear of potential punitive outcomes.1 In what has been termed the Trust-Report-Improve cycle, trust promotes reporting and improvement, which in turn fosters greater trust. In this type of culture, clinicians are more likely to learn that their reporting actually contributes to improvements in patient safety and quality of care.1 However, despite efforts to improve reporting, studies cite common barriers to achieving optimal benchmarks that include lack of knowledge on how to report ADRs, uncertainty as to whether the reaction observed was caused by a drug, perception that the reaction was too well recognized to be reported again, concern over potential legal liability, among others (Figure 1).2 In acknowledgement of these challenges, TJC issued an alert urging leadership to develop a reporting culture in their organizations. This reporting culture is further described as a “psychologically safe” environment where there is a commitment of reassurance that there will be no negative consequences for reporting unsafe events or conditions.3 While medication errors have been discretely and specifically classified by the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP), leaving little room for uncertainty or debate when describing and reporting, the lack of a consistent definition for ADRs has continued to perpetuate controversy among reporters, prescribers and quality management leadership alike.4

Regulatory bodies and the patient safety community, including the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), defines an adverse drug event (ADE) as an event when an individual is harmed by a medicine and can include both medication errors and ADRs.5 Unlike ADRs, an ADE does not necessarily have a causal association between the event and the drug.6

According to Nebeker et al,7 the lack of consensus for a common definition of an ADR has been a longstanding barrier contributing to the ongoing discouragement of prescribers to recognize and report ADRs.8 Citing that physicians “commonly classify gastrointestinal (GI) adverse reactions as side effects because they believe them to be unavoidable and common consequences of medication administration versus a clinically significant manifestation,” the authors express concern that prescribers might unintentionally subject patients to additional unnecessary drug exposure when seemingly benign “side effects” are treated with additional drugs in a prescribing cascade. The authors conclude from examples, such as constipation caused by narcotics and nausea from antibiotics that ADRs reported to occur so frequently, with only a small percentage causing serious harm, that prescribers will overlook the likelihood that even this small percentage of occurrence translates into a significant impact when one considers the overall number of ADRs potentially experienced.7 Due to the continued confusion over definitions and the increased likelihood that the use of the term “side effect” minimizes the potential injury from drugs, no matter how seemingly insignificant, the international pharmacovigilance community has recommended that this designation no longer be used (Table 1).7,9 This definitional debate, coupled with the encouragement by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to only report events that are unexpected or serious for the general population, reinforces the need to strengthen pharmacovigilance programs that both monitor for, and prompt reporting of, rationale for prescribing actions for all potential ADRs within psychiatric hospitals and for patients with comorbid psychiatric illness.6

The implementation of electronic medical records (EMR) and computerized physician order entry (CPOE) has resulted in a more efficient process of addressing ADRs and modifying the medication regimen. These technologic advancements might also offer opportunities to overcome previous challenges of systematically reviewing data for quality improvement purposes; however, they do little to offset negative prescriber perceptions questioning value in making the effort or concerning potential punitive outcomes with reporting. There is increasing evidence that ADRs might have demographic predisposition, with subgroup populations, including women, more likely to experience more ADRs. With increased overall reporting and enhanced efforts to capture optimal details on these events, we can contribute to the evolving and emerging health and safety information available as well as capturing a better understanding of the potential underlying biology associated with race, age, and sex among other demographic factors most likely to be associated with these differences.11

Objectives

The primary outcome of our study was to determine whether or not prescriber initiated medication discontinuations, which require rationale in order to finalize a discontinuation order, were potentially unreported ADRs and whether these aligned with official ADR reports received by Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee for the inpatient state psychiatric facility of record. We hypothesize that prescriber-initiated discontinuations are often unreported ADRs and that prompting prescriber rationale for medication changes might facilitate a more robust reporting system that could result in stronger medication safety surveillance programs.

Methods

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of record for the facility (New York State Psychiatric Institute). A retrospective review of ADRs submitted to, and reviewed by, the facility’s Pharmacy and Therapeutics (P&T) committee June 1, 2019, to July 1, 2020, as well as a review of all prescriber initiated drug discontinuation reports (DDR) received by the facility and entered into the de-identified pharmacy database during that same period of time.

Inclusion criteria included reports that occurred during the specified time period and associated with patients 18 years of age or older and who were inpatients at the state psychiatric center at any time between June 1, 2019, and July 1, 2020. Patients admitted prior to or after these dates and those with known Criminal Procedure Law (CPL) status were excluded.

Results

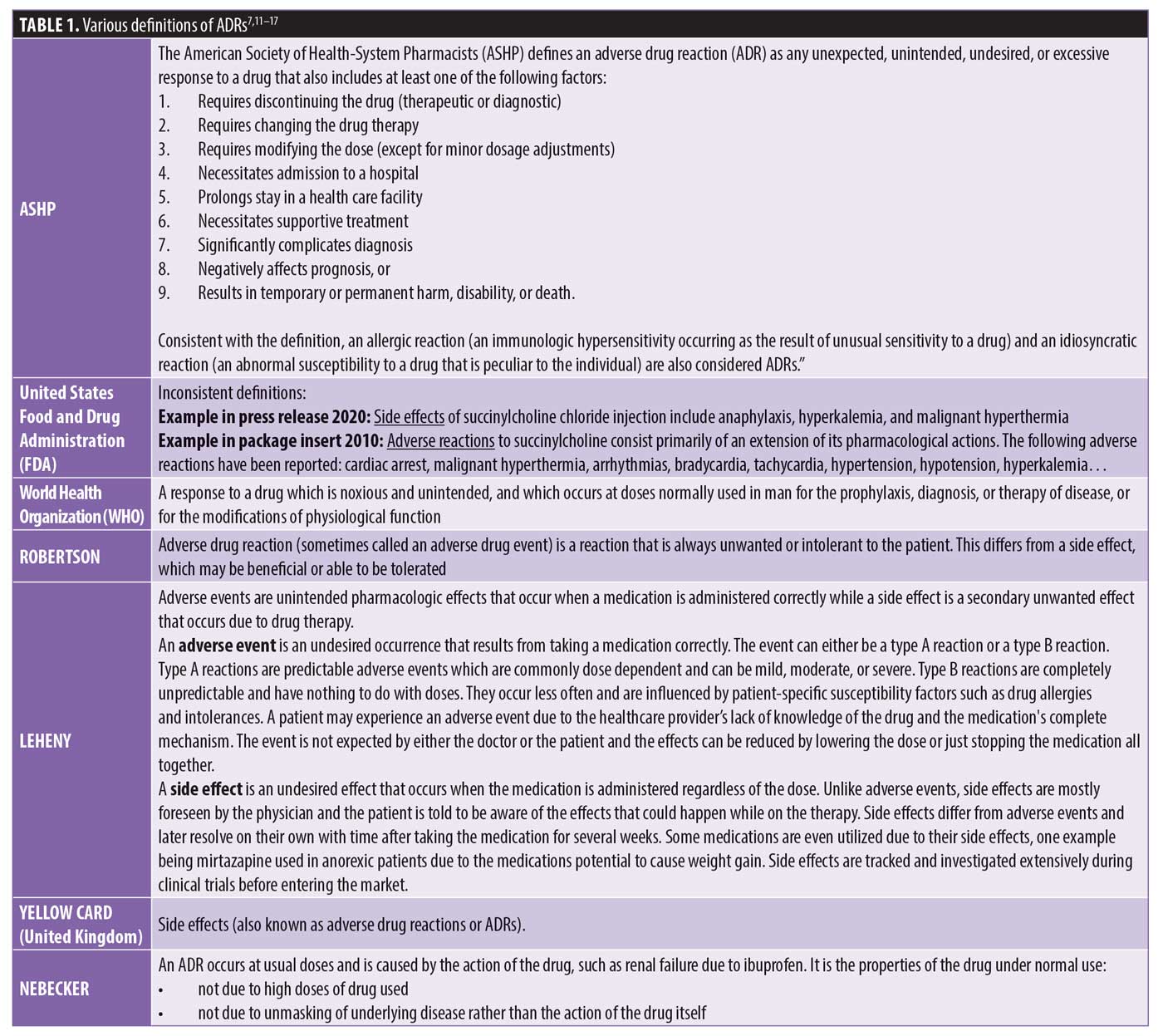

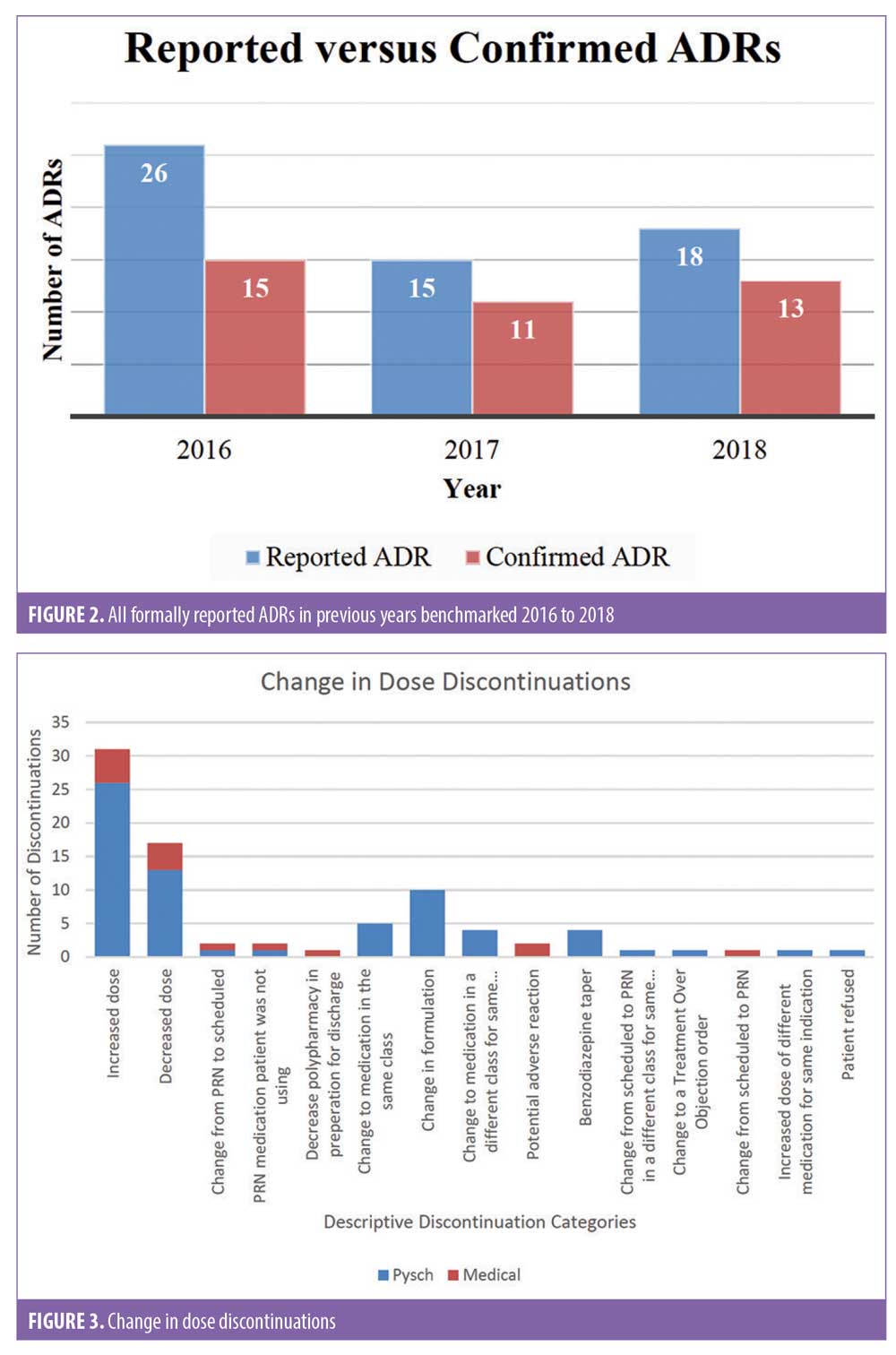

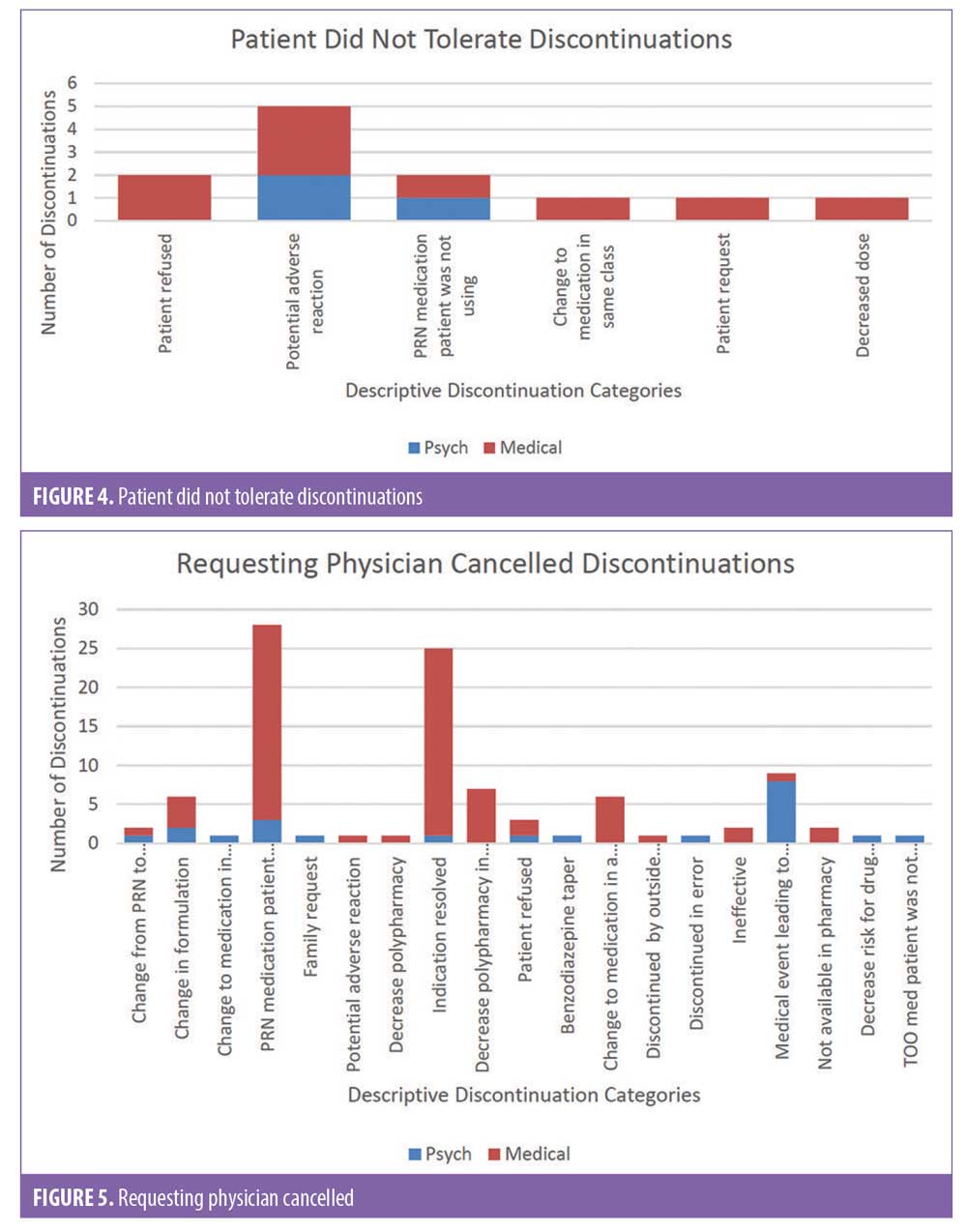

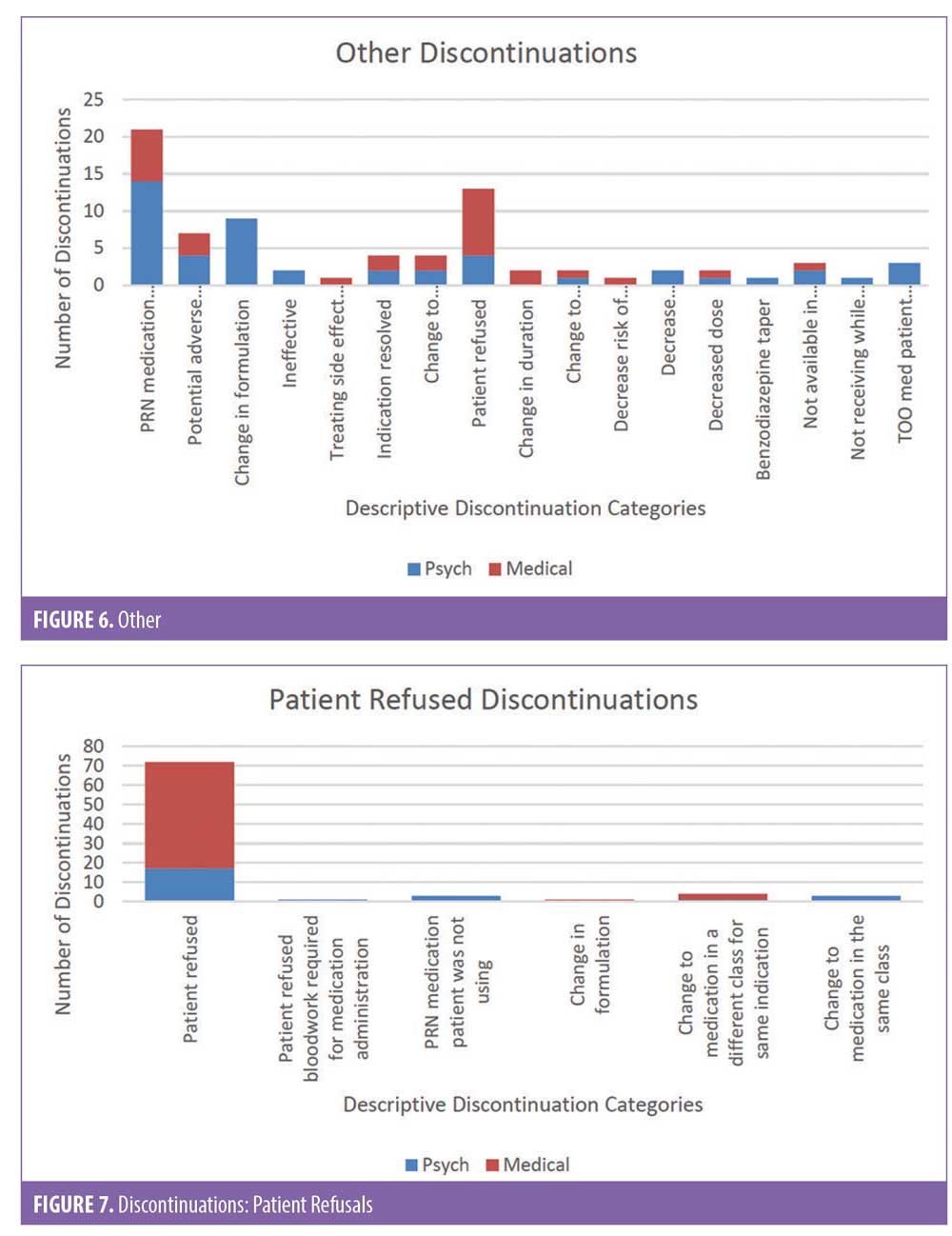

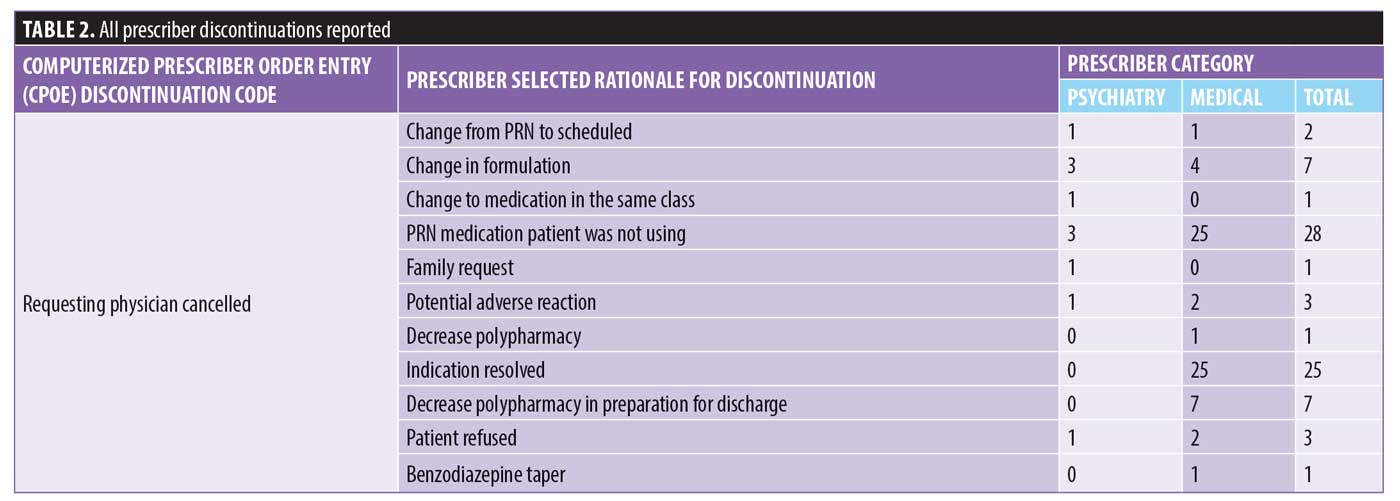

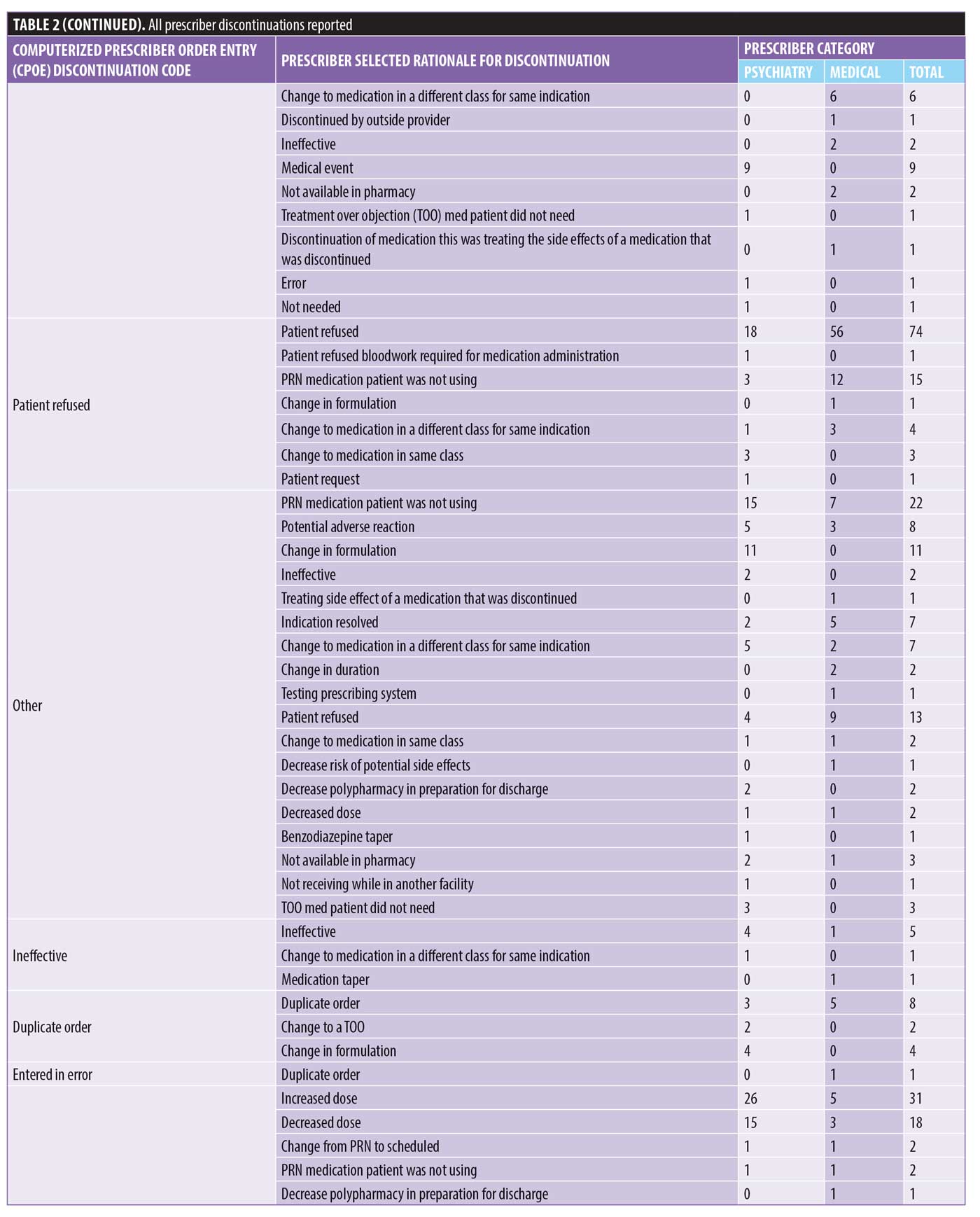

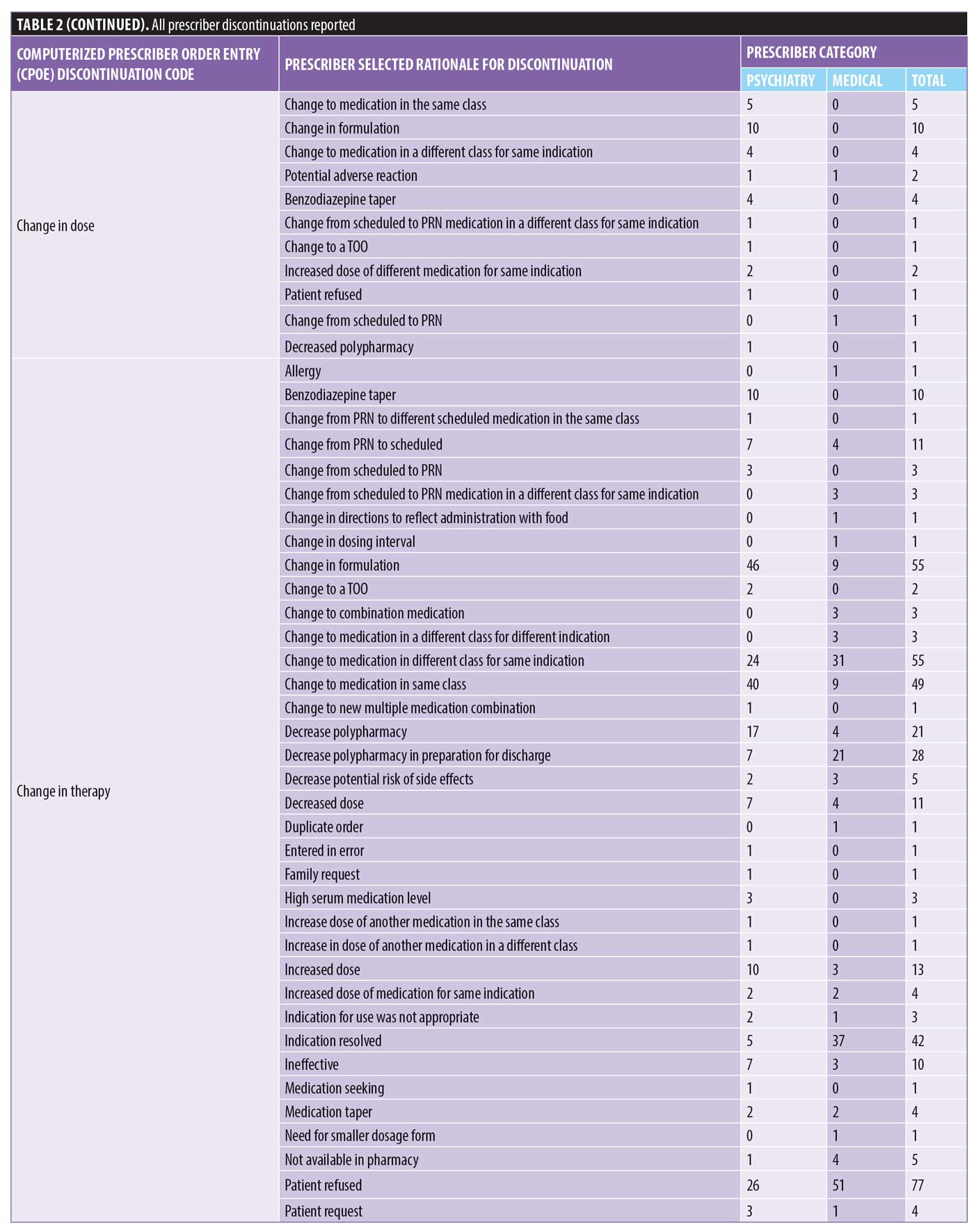

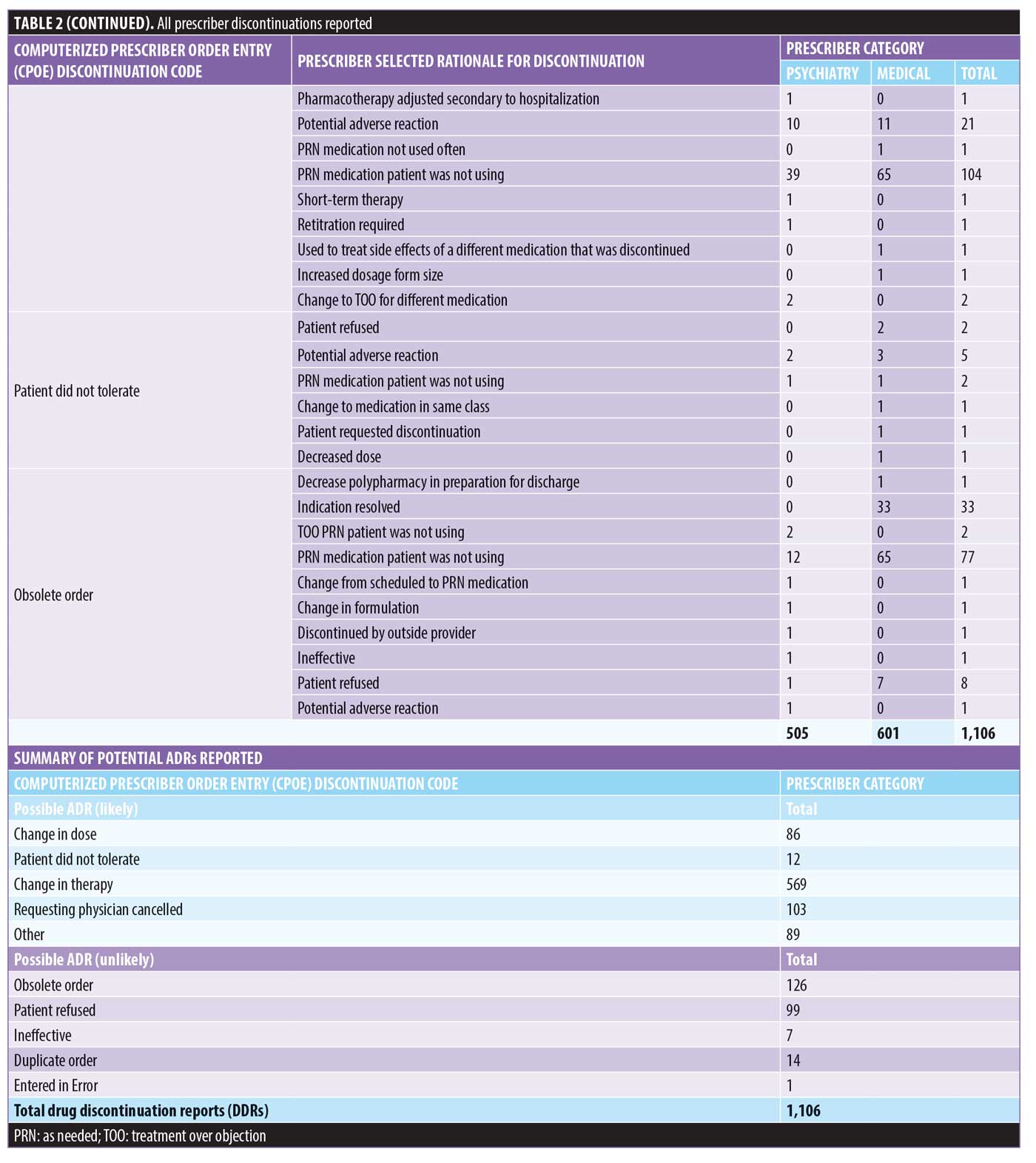

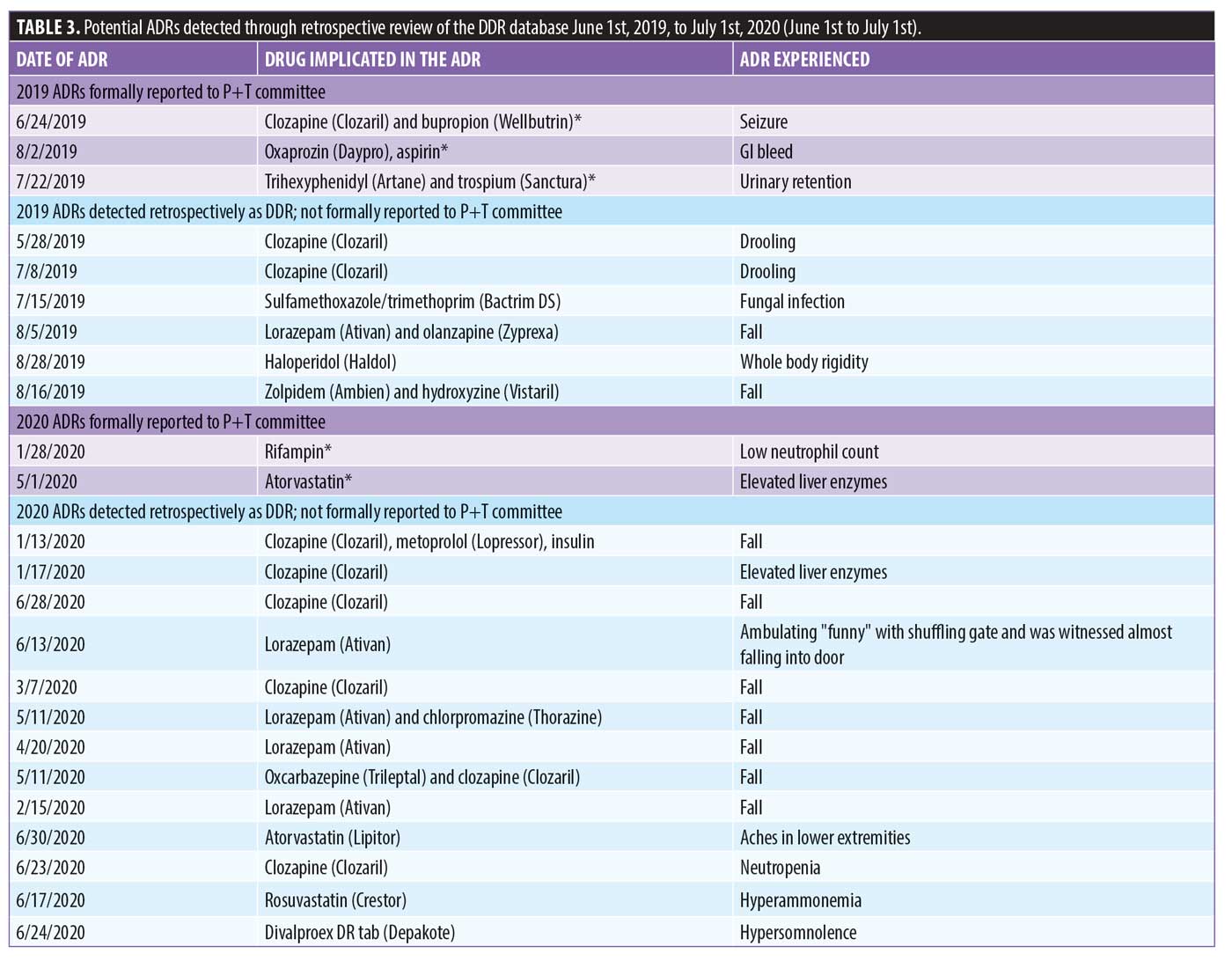

There were 1,106 deidentified drug discontinuation reports (DDRs), the greatest number of discontinuations reported were categorized as change in therapy and which were roughly equally represented with 25 percent involving medical medications (N=279) and 26 percent involving psychiatric medications (N=290) (see Table 2). The remaining discontinuations were reported as obsolete order (N=126), requesting physician cancelled (N=103), patient refused (N=99), change in dose (N=86), other (N=89), duplicate order (N=14), patient did not tolerate (N=12), ineffective (N=7), and entered in error (N=1) (Figures 3-7). The formal ADR reports were significantly fewer when compared with the discontinuation reports, and when benchmarked with the previous two years, did not vary considerably (Figure 2). We discovered five of the formal ADR reports were represented in the DDRs, but no DDR was formally reported to the P+T committee as an official ADR. For regimens that were modified with change in dose only, the majority were dose increases in psychiatric medications, and thus unlikely ADRs (Table 3).

Discussion

This study found that prescribers initiate medication changes in response to potential adverse drug effects. We also reported that when provided with tools that prompt inclusion of a rationale for such medication changes, the correlation of regimen changes in response to adverse effects becomes clearer. Because there is evidence that prescribers might perceive the term reaction as an outcome of bad prescribing, it important to continue exploring differences in perceptions and definitions of ADRs as well as sharing the value of lessons learned in benchmarking and targeting efforts to reduce the incidence of ADRs, no matter how seemingly small or benign the adverse drug effect. Previous successful efforts have centered on establishing a reporting culture that focuses on systems issues, rather than on individual healthcare professionals and that have developed surveillance teams that monitor and review reports.

Limitations. One weakness of our study was the inability to capture all electronic discontinuations since the current system only permits manual collection of the change notices from the printer in the pharmacy department. Therefore, there might have been additional discontinuations that were not evaluated. The seemingly low reporting of formal ADRs might be due to prescriber negative perception; however, this was unable to be determined without a survey or perception scale to confirm this potential barrier to reporting ADRs within the facility of record and we recommend that further research be conducted to evaluate this unknown. The forced functionality that required a rationale for discontinuation appears to be a potentially positive element to improving medication use evaluation with the additional detail known.

Conclusion

We conclude that adopting a nonpunitive approach to addressing ADRs is likely to encourage reporting by those who otherwise might fear retribution or hospital disciplinary action. It has been suggested that prescribers would favor a system that includes their participation in the reporting and investigating process early in the discovery with opportunity to weigh in on the event before a final determination is made. Safety surveillance programs have identified challenges associated with the reporting of possible ADRs as a potential patient safety issue. In addition to the potentially negative perception of ADRs, prescribers can also be reluctant to report due to time constraints and lack of overall knowledge about these events, which includes confusion about the definition of ADRs in general. Our belief that most prescriber-initiated discontinuations in our study were likely ADRs not reported formally to the P+T committee for further review was also validated. Further studies are warranted on both the potential impact of negative prescriber perceptions and general knowledge about the definition and benefit in reporting ADRs, which can contribute to emerging and evolving medication safety data labeling. We advocate for consideration of any new condition, symptom emergence, or change in status to be a possible ADR, especially in older adults and in patients with comorbid psychiatric illness, and that these reports are used to inform future improvement in patient safety efforts.

References

- Patient Safety Systems (PS) site. https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/idev-imports/blogs/ps_chapter_omepdf.pdf. Accessed 1 Sept 2021.

- Elnour AA, Ahmed AD, Yousif MAE, Shehab A. Awareness and reporting of adverse drug reactions among health care professionals in Sudan. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2009;35(6):324–AP2.

- The Joint Commission Sentinel Event site. 1 Mar 2017 https://www.jointcommission.org/-/media/tjc/documents/resources/patient-safety-topics/sentinel-event/sea_57_safety_culture_leadership_0317pdf.pdf.

Accessed 1 Sept 2021. - The National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP) site. https://www.nccmerp.org/. Accessed 1 Sept 2021.

- The Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) site. https://www.cdc.gov/medicationsafety/adult_adversedrugevents.html. Medication Safety Program.

Accessed 1 Sept 2021. - FDA #2 Guideline for Postmarketing Reporting of adverse drug experiences. Rockville, MD: US Food and Drug Administration; 1992.

- Nebeker JR, Barach P, Samore MH. Clarifying adverse drug events: a clinician’s guide to terminology, documentation, and reporting. Ann Intern Med. 004;140(10):795–801.

- Classen DC, Pestotnik SL, Evans RS, Burke JP. Computerized surveillance of adverse drug events in hospital patients. JAMA. 1991;266:2847–2851.

- Cobert BL, Biron P. Pharmacovigilance from A to Z. Malden, MA: Blackwell Science; 2002.

- Parekh A, Fadiran EO, Uhl K, Throckmorton DC. Adverse effects in women: implications for drug development and regulatory policies. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2011;4(4):

453–466. - American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. ASHP guidelines on adverse drug reaction monitoring and reporting. Am J Health-Syst Pharm.1995;52(4):417–419.

- FDA site. Coronavirus (COVID-19) update: daily roundup June 17, 2020. www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/coronavirus-covid-19-update-daily-roundup-june-17-2020. Accessed 1 Sept 2021.

- Anectine (succinylcholine) package insert. Princeton, NJ: Sandoz Inc; 2010.

- World Health Organization. International monitoring of adverse reactions to drugs adverse reaction terminology. In: International monitoring of adverse reactions to drugs adverse reaction terminology. WHO Collaborating Centre for International Drug Monitoring. 1989.

- Robertson D. Essentials of pharmacology for nurses, fourth edition. London, Eng: Open University Press; 2015

- Leheny, S. ‘Adverse event,’ not the same as ‘side effect’. 22 Feb 2017. https://www.pharmacytimes.com/contributor/shelby-leheny-pharmd-candidate-2017/2017/02/adverse-event-not-the-same-as-side-effect. Accessed 1 Sept 2021.

- UK Yellow Card Scheme site. https://yellowcard.mhra.gov.uk/search/?q=mhra&Search.x=0&Search.y=0&Search=Search. Accessed 1 Sept 2021.