by Anjuli S. Maharaj, DO, PGY-3 in Psychiatry; Nita V. Bhatt, MD, MPH; and Julie P. Gentile, MD

by Anjuli S. Maharaj, DO, PGY-3 in Psychiatry; Nita V. Bhatt, MD, MPH; and Julie P. Gentile, MD

Dr Maharaj is with Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine in Fairborn, Ohio. Dr. Bhatt is the Associate Director of Medical Student Education in Psychiatry at Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine in Fairborn, Ohio. Dr. Gentile is the Chair of Psychiatry at Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine in Fairborn, Ohio.

FUNDING: No funding was provided for this study.

DISCLOSURES: The author has no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: It is well documented that people of color face disparities in access to and quality of healthcare. There are inequities in healthcare outcomes as well. The biases of healthcare providers are one of the many factors that contribute to healthcare incongruence. Often overlooked, race impacts therapeutic relationships and highlights ingrained patterns of binary thinking, thereby creating hierarchies. Some physicians experience anxiety regarding addressing racism, leading to avoidance of its existence and effects on the physician–patient alliance. Others address the dynamics by bringing the patient’s family experiences and lived experience “in the room.” By following the “emotional red thread,” we can bring clarity to the issue of making racism a neutral topic of conversation in treatment. As it has so often in the past, racism should not and cannot be ignored.

Keywords: Structural racism, psychotherapy, health inequities, mental health, race, discrimination, healthcare disparities, implicit bias, transference, countertransference

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2021;18(7–9):39-43

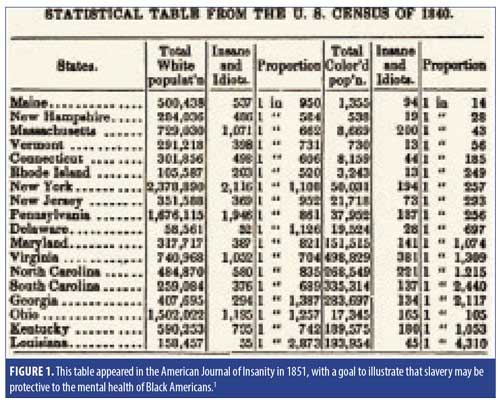

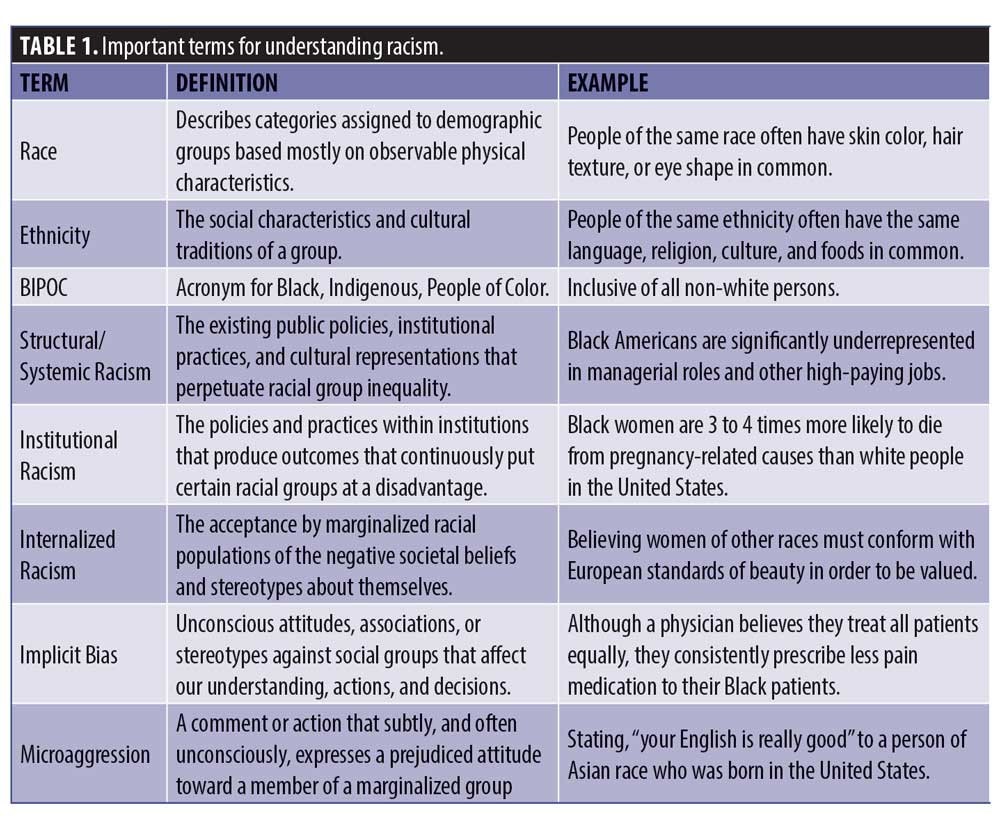

The United States (US) has had a biased view of mental healthcare for Black Americans for centuries. The 1840 US census was among the first data that addressed mental illness in the Black community. Through flawed methodology,1 the data purported northern states had more than 10 times the amount of mental illness (at that time described as “insane” and “idiots”) than the pro-slavery southern states. This allowed for slavery to be interpreted as a benign institution, one that protected Black people from developing mental illness.1 This is but one example of the history that laid the framework for the structural racism that exists today. Structural racism refers to the ways in which societies foster racial discrimination through mutually reinforcing systems of housing, education, employment, earnings, benefits, media, healthcare, and criminal justice. These patterns and practices reinforce discriminatory beliefs, values, and distribution of resources.2 The concepts of structural racism and institutional racism should be integrated with interpersonal racism.2 Studies have shown that there is bias among healthcare providers across multiple levels of training and disciplines.3 Indeed, the attitudes and behaviors of healthcare providers have been identified as one of many factors that contribute to health disparities.3 Implicit attitudes are thoughts and feelings that often exist outside of conscious awareness, and thus are difficult to consciously acknowledge and control. These attitudes are often automatically activated and can influence human behavior without conscious volition. This article will review the treatment dynamics created by racism as well as the approaches that the physician can utilize in a therapeutic manner. While much of the research on racism and health is focused on Black Americans, experiences of other non-white minority groups (Latinos and Asian Americans) are included in this article as clinical vignettes to capture a breadth of understanding across cultures.

Discussions About Race

Talking about race is difficult for many providers. “Not seeing” is a phenomenon described in the literature wherein individuals defy or deny the issue. This might be considered conflict avoidant or refusal to confront detrimental or painful assumptions. In 2008, Apfelbaum et al4 conducted a study that allowed white people to achieve results more effectively by asking a person about their race. Many of them avoided doing so. The study was repeated with white children, who responded similarly. The study found that this strategy was internalized by the average age of 10 years in white children.4 “Not seeing” was a norm as opposed to speaking in a positive or neutral manner about race. White people were more likely to discuss race unambiguously if they were paired with another white person, whereas if they were paired with a Black person, they did not broach the topic until the Black person modeled openness and acknowledged the topic.4

This mirrors clinical practice, which shifts the responsibility of a race conversation in a black-white dyad to the Black person. This is true no matter if the Black person is the patient or the physician. This intrinsically creates lack of clarity in the countertransference and infringement of the boundaries. It seems like quite the dichotomy to “not see” or “not talk” about race in the context of a therapeutic relationship. After all, is this not the room where our goal is to improve a patient’s well-being, physical, and mental health? To resolve or mitigate troublesome behaviors, beliefs, compulsions, thoughts, or emotions? And ultimately, we hope to attain self-growth and to improve relationships and social skills. The use of neutrality regarding race will create or sustain structural racism. The white therapist treating a Black patient exactly the same as they would treat a white patient fails to address their experiences of racism and miss significant personal issues.

CLINICAL CASE VIGNETTE 1:

Mr. B is a 27-year-old Hispanic male with a history of generalized anxiety disorder who has been attending weekly psychotherapy for eight weeks. His therapist is Dr. T, a middle-aged white male with 20 years of experience. Mr. B is a first generation American, and his parents immigrated from Mexico before Mr. B was born. Mr. B lives with his parents, younger sister, maternal aunt, and maternal grandparents in the same house. Mr. B’s family speaks Spanish at home, and Mr. B’s grandparents do not speak English. Mr. B’s grandfather has been feeling ill with abdominal pain for some time but refused to go to the doctor despite Mr. B’s pleading. Therapy sessions thus far have focused primarily on Mr. B’s anxiety symptoms and tumultuous relationship with his longtime girlfriend; however, Dr. T is aware of Mr. B’s family dynamics from intake sessions. Mr. B had cancelled his last therapy session with Dr. T, citing a family emergency. Mr. B presents for his ninth psychotherapy session looking more troubled than usual.

Doctor T: What’s on your mind today, Mr. B?

Mr. B: The day after our last session, we ended up rushing my abuelo…that’s my grandpa…we rushed him to the emergency room because he was in so much pain. He kept saying, “no, no,” but we took him anyway. He was admitted to the hospital and did all of these tests on him, and it turns out he has a big tumor in his intestines. He was in the hospital for over a week.

Doctor T: I’m sorry to hear that. How are you handling all of this?

Mr. B: Well, I ended up staying with him at the hospital the whole time because it was easier for me to translate to him what the doctors were saying rather than waiting on the interpreter. That was exhausting. And I’ve been feeling really conflicted about some things lately.

Doctor T: How so?

Mr. B: At first, I was angry at my abuelo for refusing to go to the doctor and resisting the hospital. I thought if he had just gone when he first felt his pain, maybe this all could have been avoided. Why wouldn’t he want to take care of his health? But then when were at the hospital, I feel like I understood why. I felt like the doctors didn’t spend as much time with him because of all the translating. I could see the relief on their faces when they realized I spoke English as well as them. But if I wasn’t there, he didn’t want to call for the nurse or ask for help. He was really in pain, and I don’t feel like the doctors took him seriously. It actually made me angry. And it made me angrier once I realized this is why my abuelo wanted to avoid the doctor…because he expected it. I wonder what kind of bad experiences he has had just because he’s Mexican.

Practice Point

Intergenerational trauma. Intergenerational trauma can be understood as the ongoing impact of traumatic events that happened in prior generations and continues to impact the current generation. Trauma can be passed down through a multitude of factors, including epigenetic processes that increase vulnerability to various mental disorders, repeated patterns of abusive or neglectful behavior, poor parent–child relationships, negative beliefs about parenting, personality disorders, substance abuse, family violence, sexual abuse, and unhealthy behavior patterns and attitudes.5 Ethnic minorities have high rates of intergenerational trauma due to traumatic experiences of racism. Well-known examples include the children of both Holocaust survivors and enslaved Black Americans. A 2018 systematic review of 30 studies looked at how children’s health might be affected by indirectly experienced racism. Researchers concluded that “socioemotional and mental health outcomes were most commonly reported with statistically significant associations with vicarious racism.”6 Anxiety is a common symptom of those raised in environments with family members who have experienced direct and traumatic racism.5 LaMothe7 reported on the trauma of racism and how the psychotherapist can navigate these issues in the room. As LaMothe stated so eloquently, the goal is to “answer the question of how individuals and groups survive and, in many cases, flourish in spite of the traumatizing milieu of racism.” 7 It is important to understand, acknowledge, and educate about intergenerational trauma to patients and providers alike. Informed therapy for patients of color might not only promote healing within themselves, but also for future generations.

CLINICAL VIGNETTE 1, CONTINUED:

Doctor T: How does it feel to say these concerns out loud to me?

Mr. B: I don’t know…it’s awkward, I guess. We haven’t really talked about this kind of thing before. I don’t want you to think that I mean all white doctors are bad.

The session continues with an honest, albeit uncomfortable and clunky, conversation about reconciling Mr. B’s identities as both Mexican and American. Mr. B tiptoes around the subject of explicit racism, and Dr. T follows his lead and spends much of the session listening keenly. Afterward, Dr. T sits in his office and attempts to finish his notes, but he cannot shake a sense of inner emotional discord. “What kind of safe space am I creating if Mr. B is hesitant about talking about racism because I am white?” he thought. He recalled something his college-aged daughter mentioned to him about microaggressions. “What if I prove him right by inadvertently saying something offensive?” Suddenly, his whiteness became the elephant in the room. To strengthen their therapeutic alliance, Dr. T decided to address it at the next session. He was no stranger to working through emotions that arise in the room; so why did this feel so daunting?

Addressing Race in Psychotherapy

In a 2014 study at the Trauma Research Institute in San Diego, California, 35 Black and Hispanic patients were paired with White therapists and interviewed about their experiences. Eighty-two percent of patients indicated that a problem in communication occurred with their therapist that they believed had to do with race or cultural differences.8 There was a notable lack of discussion of race in the therapeutic dialogue; 36 percent of the participants indicated that their White therapist never mentioned race at all.8 Establishing goals and major themes in therapy early on might allow the patient to bring this up, but many patients might hesitate to bring up race as important to them until a rapport is established. Incorporating questions about race and racism during intake sessions with explanation about why the topic of race is therapeutically relevant will encourage a safe space for discussion. White physicians and therapists might choose to acknowledge their racial difference or racial privilege in discussions of race with patients. This can be done by asking the patient if there was any concern that their racial difference made it difficult to bring important and difficult topics into the room, or if it was hard for them to bring certain issues to therapy because the therapist did not have to face daily racism (as the patient did). Finally, knowledge of available mental or general healthcare resources particular to patients of color is essential in demonstrating culturally competent care.

Practice Point

Transference, countertransference, and implicit bias. It is important to recognize when transference or countertransference arises in any patient encounter. Transference can be conceptualized as the patient experiencing certain emotions toward their therapist or provider based on their own experiences with others in their life. Countertransference is essentially the reverse, with the therapist or provider battling emotions that the patient evokes in them based on their experiences with someone else. While not all transference and countertransference are negative, they do have the potential to hinder the patient’s progress if unrecognized and unaddressed. Utilizing an experienced supervisor or engaging in peer consultation on cases where this concern is present can be extremely beneficial to managing reactions and to ensure there is no deviation from standard of care. However, implicit bias can be more difficult to identify with oneself. Whereas countertransference might be conscious or unconscious and generally refers to the emotions evoked by one particular patient, implicit bias is any unconsciously held association or attitude about an entire demographic of people (e.g., ethnic minorities, women, disabled, or overweight populations).9 No person or profession is immune to developing implicit bias regardless of how altruistic or empathic they are, as these beliefs are often rooted in early childhood.9 In fact, there is evidence that healthcare professionals have the same level of implicit bias as the general population, and higher levels are associated with lower quality of care.10 Implicit association tests assess automatic associations between different social groups and can be an effective tool to acknowledge these “blind spots” and bring them to consciousness.9 This type of self-discovery can often be difficult to reconcile with one’s own perceived lack of explicit bias. It is important for providers to normalize the pursuit of these truths, educate others about their existence, and seek one’s own psychotherapy when indicated to explore the development of implicit biases.

Clinical Pearls

There is potential for psychotherapy to obscure rather than validate racism, injustice, and disadvantage

White physicians should be aware of available resources for patients of color to affirm their commitment to all patients’ safety

Managing transference expectations and countertransference reactions, as well as recognizing implicit biases are essential to good patient care. This can be accomplished by peer consultation, continuing supervision, and taking implicit association tests

CLINICAL CASE VIGNETTE 2

Ms. H is a 31-year-old Black female who is presenting to therapy for the first time due to concerns about increasing anxiety as she progresses through her graduate master’s program. Ms. H was born in Nigeria and immigrated to the US when she was 13 years of age. On her intake paperwork to the therapy office, she indicated that she would prefer a therapist of color, preferably of African descent. She is told over the phone that she will be working with Dr. M, as she has availability after normal business hours that would suit Ms. H’s rigorous school and work schedule. Ms. H walks into the office for her first appointment and is surprised to find that Dr. M is, in fact, a White woman. She takes a seat after Dr. M introduces herself; however, she remains quiet and is visibly uncomfortable.

Doctor M: What seems to be troubling you?

Ms. H: [looks down] I’m sorry, I don’t mean to be rude, but you look different than what I imagined. I had requested a Black therapist, and I saw on the website that there is a Black therapist who works here, so I thought that’s who I would be meeting.

Doctor M: It sounds like the racial background of your therapist is important to you.

Ms. H: Well, I just thought it would make things easier, like they would understand where I was coming from without having to explain every little thing. Like another minority person who got their degree and could relate to the pressures I’m facing. I guess I was excited at the prospect of talking to someone like that. I mean, I’m sure your experience was way different than mine is…[looks up slowly and expectantly]

Practice Point

Self-disclosure in the therapeutic relationship. Boundaries are inherent in the patient–provider relationship; the focus is designed to be completely on the patient, addressing their concerns, emotions, and hopes. However, it is natural for patients to have a curiosity about their provider’s lives. There are several schools of thought on self-disclosure in therapy, and navigating how to manage it can be a delicate and difficult process. Traditional Freudian psychoanalytic theory has a strong stance against self-disclosure by the therapist, believing that such a confrontation with the therapist’s reality would impede the patient’s ability to freely develop their own transference and work towards resolving it in therapy, thereby influencing the relationship and reducing therapeutic effectiveness.11 This neutral stance continued to be adopted by other psychological theorists and became an essential part of the therapeutic process. However, there also exist those who believe in the therapeutic power of careful self-disclosure. Henretty and Levitt described how self-disclosure can normalize the patient’s experience, help them recognize their boundaries between themselves and others, and correct misconceptions.12 Regardless, in the case of direct or leading questions posed by the patient to the therapist, it is important to determine where the “need to know” stems from and address it.11 There is a judgment call to be made by the therapist in certain situations: will self-disclosure benefit the patient, or does it have the potential to hinder the patient’s progress? In the vignette above, Ms. H appears to be making an assumption about Dr. M’s background based on the color of her skin and perceived easy educational path. It might be tempting to take offense to this; however, what Ms. H is conveying is her struggle with her own path in addition to seeking acknowledgment of the loss she feels for being assigned a different therapist. In this situation, Dr. M’s clarification of her educational experience would bypass the true issue and potentially further isolate Ms. H.

CLINICAL VIGNETTE 2, CONTINUED:

Ms. H: [Pauses, then smiles faintly] I suppose I can’t be too picky with how my schedule is though, so this will be OK. I’m sorry if I offended you.

Dr. M: No offense taken, and I appreciate you sharing that with me. Is it OK if we use this session to explore this further?

Ms. H: Well, sure, I suppose. What do you want to know?

Ms. H strongly considered not returning to therapy after that initial session. However, Dr. M had shown such a curiosity about her upbringing in Nigeria and took the time to explore why Ms. H had such trepidation about sharing her anxieties with a White woman. She gained insight into how race affected every social interaction she had. She began to question where her distrust of White people came from, and identifying structural racism became a major theme in their future sessions.

Practice Point

Racial matching of patients to therapists. Individuals from ethnic and racial minority groups in the US have been reported to underutilize mental health services compared to those from the majority group. Once they have accessed services, individuals from racial minority groups have been found to average significantly fewer treatment sessions than White clients and to drop out of therapy at significantly higher rates. One of the contributing factors to this is a lack of positive regard toward the therapist. A 2011 meta-analysis of racial/ethnic matching of patients to therapists found that there was, indeed, a moderately strong preference for a therapist of the patients’ own race as well as a tendency for patients to view therapists of their own race more positively than other therapists.16 However, there was actually no significant difference in treatment outcomes when a patient was matched with a therapist of their own race.13 In essence, if a racially different therapist is able to garner enough positive regard from the patient to keep them engaged in treatment, treatment outcomes might be just as positive as those of a racially mated therapist.

CLINICAL CASE VIGNETTE 3

Dr. K is the chief resident of surgery at his local community hospital. He was born in India, and although he spent the later part of his childhood growing up in London, he returned to attend medical school in India to be near his ailing grandmother. He worked diligently to obtain a residency in the US. Over the past five years, Dr. K has made a name for himself in the hospital not only for his surgery skills, but for his calming bedside manner as well. He is the surgery resident on call on the evening Mr. G arrives to the emergency department, writhing in pain. Mr. G is a 57-year-old White male who presents complaining of severe right upper quadrant pain. Dr. K is consulted immediately, and the work up reveals a textbook case of acute cholecystitis. After explaining the need for surgery, Dr. K asks Mr. G. to sign for informed consent. Mr. G. pauses, with his pen hovering over the signature line. He then states, “I would feel more comfortable with another doctor.” The nurse in the room, a White woman, goes on to praise Dr. K’s positive outcomes and many accolades while Dr. K stands back silently. After several minutes of stumbling over his words, Mr. G suddenly blurts out, “OK, I am not racist or anything, but I just don’t want an Indian doing my surgery. It is my right to be able to pick my doctor.” Dr. K steps out of the room with his head hung, dreading the phone call that he will have to make to his attending physician to explain why she will need to come in to do the surgery instead.

Practice Point

Addressing race with physician partners and in supervision with resident physicians. The vignette above is unfortunately not an uncommon one. A 2020 survey of physicians of color conducted by Serafini et al14 found that 23.3 percent of participants reported that a patient had openly refused their care due to their race/ethnicity, as in the scenario above. This is in addition to the 21.9 percent who reported that their care was refused, but the reason was not explicitly stated.14 Some common issues experienced by physicians of color include giving up precious time protected for assessment and collection of patient history to respond to inquiries about their training and competence. Physicians of color often begin to normalize this extra hurdle in their ability to do their job; they can internalize racism and develop a sense of inferiority due to years of societal racial hierarchy. If patients are consciously or unconsciously aware of these factors, this can play a significant role in the treatment when the patient “tests” the provider. Physicians of color should be afforded the opportunity to discuss these issues with supervisors, just as practicing physicians should have the opportunity to discuss with colleagues. If race is not acknowledged in a therapeutic space, it does not disappear. It is present beneath the surface and might come out in unexpected ways. The supervisor or colleague should acknowledge the painful interaction and identify the comments as antagonistic and unacceptable. The professional standards of a hospital-based or outpatient clinical setting should be clearly documented; any employee or patient breaching those standards should be immediately addressed. It is essential to prioritize elevating incidents of racism to the proper reporting structures. Furthermore, it is just as essential for these processes to be upheld by White colleagues and leadership. Through this consistent practice, the physician or trainee of color will feel empowered to recognize their endured racism as unacceptable. The safe space to bring these issues to light will be created, and only then can the healing from effects of racism begin.

Conclusion

Racism is a social construct that has been present across all professions, industries, and communities for centuries. Despite this, racism remains such a controversial topic that many people, even trained psychotherapists, have discomfort with it and find it difficult to address ”in the room.” Implicit biases are internalized from a young age and often never brought to consciousness. When they are discovered, using an implicit association test, further discomfort at ego-dystonic implicit beliefs can ensue. Acknowledging this discomfort is valid, even encouraged, to break the stigma associated with such a delicate topic. However, fighting this discomfort and being an active participant in the conversation about the trauma that results from experiences with racism is essential for achieving better outcomes for patients of color. Additionally, racist behavior toward healthcare providers of color must be recognized, reported, and addressed to foster a safe and effective working environment. In the end, changing the conversation about addressing race in psychotherapy cannot happen if the conversation is not started at all.

References

- Geller J. Structural racism in American psychiatry and the APA: Part 1. Psychiatr News. 2020; 55(13):2–3, 6–9.

- Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, et al. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet. 2017;389(1007):1453–1463.

- Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(12): e60–e76.

- Apfelbaum EP, Pauker K, Ambady N, et al. Learning (not) to talk about race: when older children underperform in social categorization. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(5):1513–1518.

- Adames HY, Chavez-Dueñas NY, Sharma S, La Roche MJ. Intersectionality in psychotherapy: the experiences of an AfroLatinx queer immigrant. Psychotherapy. 2018;55(1):73–79.

- Heard-Garris NJ, Cale M, Camaj L, et al. Transmitting trauma: a systematic review of vicarious racism and child health. Soc Sc Med. 2018;199: 230–240.

- LaMothe R. Potential space: creativity, resistance, and resiliency in the face of racism. Psychoanal Rev. 2012;99.6:851–876.

- Work GB, Cropper R, Dalenberg C. Talking about race in trauma psychotherapy. 2014. Society for the Advancement of Psychotherapy. http://www.societyforpsychotherapy.org/talking-about-race-in-trauma-psychotherapy. Accessed 1 Jul 2021.

- Edgoose J, Quiogue M, Sidhar K. How to Identify, understand, and unlearn implicit bias in patient care. Fam Pract Manag. 2019;26(4):29–33.

- FitzGerald C, Hurst S. Implicit bias in healthcare professionals: a systematic review. BMC Med Ethics. 2017;18(1):19.

- Tanner D. Therapist self-disclosure: the illusion of the peek-a-boo feather fan dance Part I: the art of becoming real. Int Body Psychother J. 2017;16(3):7–20.

- Henretty JR, Levitt HM. The role of therapist self-disclosure in psychotherapy: a qualitative review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2010;30(1): 63–77.

- Cabral RR, Smith TB. Racial/ethnic matching of clients and therapists in mental health services: a meta-analytic review of preferences, perceptions, and outcomes. J Couns Psychol. 2011;58;537–554.

- Serafina K, Coyer C, Speights JB, et al. Racism as experienced by physicians of color in the health care setting. Fam Med. 2020;52(4):282–287.