by Danielle Gainer, MD; Sarah Alam, BS; Harris Alam; and Hannah Redding, BA

by Danielle Gainer, MD; Sarah Alam, BS; Harris Alam; and Hannah Redding, BA

Dr. Gainer, Sarah Alam, and Ms. Redding are with Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine in Fairborn, Ohio. Harris Alam is with University of Central Florida in Orlando, Florida.

FUNDING: No funding was provided.

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

ABSTRACT: Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is a specific treatment modality that utilizes bilateral stimulation to help individuals who have experienced trauma. This stimulation can occur in a variety of forms, including left-right eye movements, tapping on the knees, headphones, or handheld buzzers, known as tappers. This type of psychotherapy allows the individuals to redefine their self-assessment and responses to a given traumatic event in eight defined steps. While EMDR is relatively new type of psychotherapy, existing literature has demonstrated positive results using this form of therapy when treating patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) by utilizing eye movements to detract from negative conceptualizations as a response to a specific trigger, while reaffirming positive self-assessments. Research indicates that EMDR could be a promising treatment for mental health issues other than PTSD, including bipolar disorder, substance use disorders, and depressive disorders. In this article, the eight fundamental processes of EMDR are illustrated through a composite case vignette and examined alongside relevant research regarding its efficacy in treating PTSD.

Keywords: EMDR, Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, psychotherapy, trauma, post-traumatic stress disorder

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2020;17(7–9):12–20

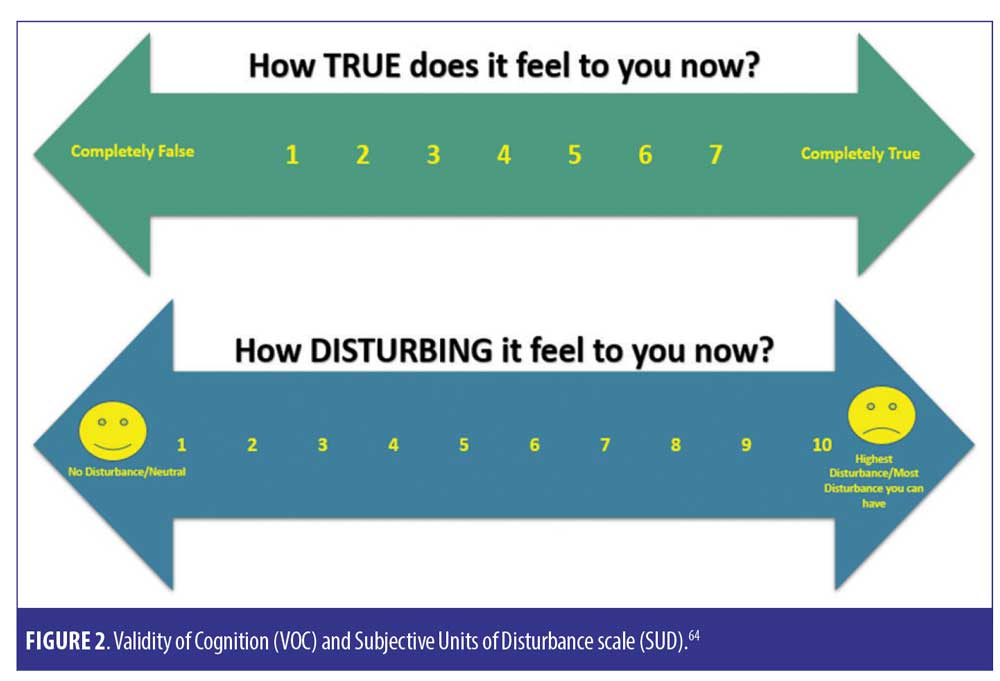

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, or EMDR, is a type of psychotherapy geared toward mitigating post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms. EMDR is an eight-step treatment modality that aims to distance patients with PTSD from the negative self-conception that can develop following traumatic events, while affirming and installing positive self-assessments.1 This is achieved by leading the patient through bilateral stimulation while talking through their traumatic memories and negative feelings, eventually introducing positive statements to replace the negative ones.1 Bilateral stimulation can occur in a variety of forms, including left-right eye movements, tapping on the knees, using headphones, or with handheld buzzers, known as tappers.2 Patients are asked to rate their negative self-assessment on a Subjective Units of Disturbance scale (SUD), which ranges from 1 (no disturbance) to 10 (worst disturbance), at the beginning and end of EMDR treatment. Patients are also asked to rate their alternate positive self-assessment on a Validity of Cognition (VOC) scale of 1 to 7 (1=totally unbelievable, 7=totally believable) at the beginning, middle, and end of a session.3 The eight stages of EMDR are 1) patient history, 2) preparation, 3) assessment, 4) desensitization, 5) installation, 6) body scan, 7) debriefing and enclosure, and 8) re-evaluation.1,4 EMDR has demonstrated significantly positive effects when examined scientifically under well-controlled environments.1,5,6

Composite Case Vignette 1

Miss M is a 26-year-old woman who presents for psychotherapy with Dr. A. She states that she has struggled with a lifelong battle of generalized anxiety symptoms, which were exacerbated by the global outbreak of COVID-19.

Dr. A: At your own pace, I’d like you to tell me a bit about your experience.

Miss M: I worked at a restaurant and was saving up to go to grad school. I was laid off within a week of the lockdown. I was living paycheck to paycheck as it was. I, um, couldn’t pay my rent that month. The landlord was a real jerk—he was always threatening to evict people who were late on payments. So, he…he told us [Miss M and her roommate] that we were out of there if we couldn’t pay. We’d been behind a few times, so I guess it was our own fault.

Dr. A: That must have been really hard to deal with.

Miss M: I took out a loan to pay the rent, but after another month of expenses I had [pause]…I had nothing. So, he… [pause]

Dr. A: It’s okay, just take your time.

Miss M: He said we had to go. And long story short, I had to move in with my parents. That wasn’t easy. They mean well, but it was…stifling. And I was useless—like, I couldn’t do anything but wait and rely on them. And then right when I got there, my grandma tested positive for coronavirus, and – [gets visibly upset]

Dr. A: [pauses and offers Miss M a tissue]. I’m so sorry.

Miss M: I can’t. I’m sorry – I don’t… I can’t talk about this. Please, just read my file. Please. I can’t talk about it.

Dr. A: It sounds as though you have been through a lot of traumatic experiences that are difficult for you to talk about. I wonder if we might try a specific type of therapy, called EMDR, to help you process some of the emotions and memories that you have.

Miss M’s grandmother passed away due to complications from the virus. Miss M is in considerable debt, has lost her financial and residential independence, and is deeply in the process of grieving for one of her primary childhood caregivers. For several weeks, memories of the illness have left her incapacitated by panic attacks, depression, and intrusive thoughts. She is unable to fully vocalize her experiences without being overcome with emotion. She agrees to learn more about EMDR and begin this type of therapy.

Historical and Theoretical Foundations of EMDR

EMDR was originally created by Dr. Francine Shapiro, whose fascination with neurological pathways led to her explore catalysts through which to rebalance the nervous system.7 This, she posited, would cause a disruption in the information that is dysfunctionally stored in the nervous system.7 This link between neural disruption and dysfunctional information storage was inspired by Shapiro’s interest in Vietnam veterans afflicted with PTSD.7 Her aim was to find these patients a means by which to manage and mitigate PTSD symptoms without raising anxiety levels.7 Shapiro stumbled upon the eye movements that are integral to EMDR accidentally: she found that otherwise recurring troublesome thoughts were disappearing and held at bay when patients experienced saccadic eye movements.7

In Shapiro’s original 1989 study, she found that memories of traumatic occurrences, including the war itself, childhood sexual abuse, physical assault, and emotional abuse, went hand-in-hand with the presentation of PTSD in the form of intrusive thoughts, insomnia, flashbacks, and interpersonal issues.8 The dependent variables measured in her experiment were a patient’s anxiety level, perceived validity of positive self-statements, and presenting complaints. She obtained measurements of these at the first session, as well as at one- and three-month follow-ups.8 Shapiro’s study (N=22) found that just one EMDR session helped desensitize the patients to their traumatic memories and shifted their cognitive perceptions of the circumstances. These outcomes were sustained at the three-month follow-up visit.8

There are two prevailing hypotheses regarding EMDR’s efficacy. The first is that eye movements facilitate communication between the left and right hemispheres of the brain.9,10 When this happens, individuals are purported to be able to recall unpleasant events without negative psychological or physical ramifications.11 Under this hypothesis, it is not important which sensory channels incentivize communication between the left and right hemispheres but that there is an alternating and rhythmic left-right stimulus.12 Left-right beeping, tactile simulation, or visual stimuli can potentially create interhemispheric communication.9

The second hypothesis is that EMDR places a stress on working memory during recall experiences.9 Working memory is “a function of short-term memory that provides temporary storage and manipulation of the information necessary for cognitive tasks such as language comprehension, learning, and reasoning,”13 while long-term memory contains inactive memories and knowledge. While the capacity of long-term memory is extensive, that of working memory is limited.12 By taxing working memory, EMDR inhibits the negative effects of unpleasant memories on individuals with PTSD.14

EMDR as a Treatment for PTSD

PSTD symptoms occur as a response to memories of traumatic occurrences.15 The use of behavior modification exposure practices, including flooding and systematic desensitization, is not a new phenomenon in treating these triggering memories.16,17 However, clinical applications of these methods have indicated these practices can cause trauma or disturbance in patients, leading to the requirement of numerous sessions in order to make progress.15

A 1998 study conducted by Carlson et al found that military veterans exposed to EMDR experienced a 77-percent remission in their PTSD diagnosis within 12 sessions.18 A meta-analysis conducted by Van Etten and Taylor found that EMDR was just as, if not more than, effective as exposure therapy in its ability to minimize PTSD symptoms efficiently.19 Findings from a randomized EMDR trial conducted by Edmond et al that included adult sexual assault survivors indicated that EMDR was more effective than routine treatment of minimizing PTSD.20

Randomized clinical trials with EMDR and CBT for adult patients with PTSD indicate that EMDR was just as, if not more, effective as cognitive behavioral therapy in symptom mitigation, without requiring patients to complete “homework” in between psychiatric visits.21

A review article evaluating EMDR as a group protocol indicated positive effects on 236 children suffering from PTSD following an Italian plane crash.22 Two other 2006 studies served to further the scientific community’s understanding of the effects of EMDR among survivors of natural disasters: the first review article showed the positive effects of EMDR as a group protocol among children following a Mexican flood,23 and the second highlighted the efficacy of EMDR as an individual treatment among 1,500 adult earthquake survivors in Turkey.24

In a 2018 study by Gil-Jardiné et al, researchers evaluated individuals who visited an emergency room following a traumatic event.25 Their findings indicated that approximately 20 percent of the subjects would go on to have life-long post-traumatic stress symptoms that severely impacted their quality of life, including post-concussion like symptoms (PCLS).25 One-hundred abnd thirty subjects at high risk for PCLS were randomly placed into three groups: one group received EMDR, another received reassurance, and the last served as a control group. The study found that 65 percent of the control group, 37 percent of the reassurance group, and 18 percent of the EMDR group were found to have PCLS three months after their initial visit. The same study found that 19 percent of the control group, 16 percent of the reassurance group, and only three percent of the EMDR group were found to have PTSD symptoms. This study supports the use of EMDR in an acute setting.25

A 2020 study conducted by Proudluck and colleagues (N=72) found that the majority of the patients who had experienced at least one traumatic event needed less than 10 EMDR sessions to experience a return to a stable mental state, with no referral for additional psychological treatment.26 EMDR has also yielded promising results among female patients with cancer: In randomized, controlled trial published in 2018, researchers found that PTSD, anxiety, and depression rates were significantly lower among women with cancer who received EMDR than among a control group who did not.27

One of the most positive findings of EMDR is that it does not necessarily need to be confined to an in-person, in-office setting in order to be effective.28 A study of the effects of varying EMDR formats on veterans with PTSD found that EMDR treatments were equally effective when done in weekly one-one-one sessions or in ntensive 10-day daily group sessions. In both cases, EMDR yielded significant treatment outcomes that were sustained at one-year follow-up.28 In summary, research has indicated that this treatment can yield beneficial results across various age groups and treatment formats.

Neurobiology Involved with EMDR

A 2017 study by Bossini et al analyzing shifts in the brain following EMDR treatment found no changes in brain scans for controls after three months, while finding significant changes in brain scans of the EMDR patients.29 These changes included increased grey matter volume (GMV) in left parahippocampal gyrus and a significant decrease in GMV in the left thalamus region. At the end of the study, 16 out of 19 patients in the EMDR group no longer met criteria for a diagnosis of PTSD, which was reflected as a significant improvement on the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale.29

Another study conducted by Santarnecchi and colleagues showed an increased connectivity between the right temporal pole and the bilateral superior medial frontal gyrus, as well as a decrease in connectivity between the left temporal pole and the left cuneus in patients following EMDR therapy.30 Findings of greater connectivity between temporal pole and prefrontal regions might indicate heightened control of trauma-related memories and thoughts, minimizing their intrusiveness during everyday scenarios.31 Generally speaking, this indicates that mitigation of PTSD symptoms is not limited to the sphere of sensorial processing, but might actually encompass cognitive networks as well.30

Propper and Christman32 hypothesized that when both the right- and left-brain hemispheres are stimulated during EMDR, memory processing is improved through enhanced interhemispheric communication via the corpus callosum. Left and right saccadic horizontal eye movements have been shown to selectively stimulate the contralateral hemisphere.33 Christman et al conveyed that left and right saccadic horizontal eye movements decreased asymmetries in hemispheric activation, resulting in equal activation of both hemispheres.33 Additionally, interhemispheric electroencephalographic interactions increase significantly during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep, and these interactions have been specifically linked to left and right saccadic horizontal eye movements.32 However, many studies have reported significant saccade-induced enhancements in memory retrieval in individuals who are strongly right- or left-handed, but not individuals who are mixed-handed.10 Individuals who are mixed-handed have a larger corpus collosum, which might enhance the communication between hemispheres.10

Though the exact mechanisms by which EMDR operates are unknown, the aforementioned studies suggest that EMDR does not place a “damper” on PTSD symptoms but that it helps to rewire cognitive processes, undoing the psychological damage caused by traumatic experiences and mitigating the presentation of PTSD.

The Eight Phases of EMDR

The overall goal of EMDR is to empower patients to process traumatic experiences and improve general quality of life.34 The process by which this is done is divided into eight major phases.5 First, individuals are asked to recall unpleasant or triggering memories for a predetermined amount of time, usually several seconds. They are then asked to rate these memories by vividness of recall and emotionality of experience (e.g., discomfort, unpleasantness, sadness). Next, the individuals are asked to recall these memories once again, but for a longer period (between 20 and 30 seconds). While experiencing this second recall, the individuals might be left to do so without a dual task (known as “recall only”), or they might be directed to make eye movements during their recall period (“recall and eye movements”). After a break in recalls, which might last over a span of minutes or days, patients are asked to recall their memories under the same circumstances as the first time. Then they are asked to rate the experience once again in terms of vividness and emotionality.35

Phase 1: patient history

Phase 1 occurs over the course of the first few sessions, but might extend throughout the rest of the process, especially if new trauma occurs.5 During this time, the therapist and patient discuss the problem that motivated the patient to seek treatment, as well as the behaviors and symptoms resulting from this problem.4 This is known as the “target event.”3 The therapist will utilize standard intake questionnaires and diagnostic psychometrics. These initial conversations and questions will help the therapist to identify three factors that will guide the remainder of the process: past events that created the problem, current situations that cause or exacerbate distress, and behaviors, coping mechanisms, and practices integral to future well-being.2

Phase 2: preparation

During Pase 2, the patient becomes acclimated to the treatment.5 First and foremost, it is imperative that the therapist create a safe space for the patient, making sure that the patient knows he or she is free to stop at any time.4 The therapist takes care to explain each step of the process and its purpose, allowing the patient to practice eye movements and other processes. Additionally, the therapist will teach the patient a number of relaxation practices that can be used by the patient when faced with an emotional disturbance.5 This might occur over the course of one or four sessions, depending on the patient’s needs and trauma levels. The overarching goal of this stage is to establish a foundation of trust between the therapist and the patient.5

Phase 3: assessment

Phase 3 seeks to access the traumatic memories that are being targeted by EMDR.5 It does not necessarily mean the patient will be required to relive or recall the memory in its entirety; rather, the patient may be asked to choose one evocative image that represents the memory to them.

Then the patient is asked to vocalize a negative self-assessment or belief that is triggered by this memory (e.g., “I am weak and in danger.”).5 The patient will be asked to vocalize the emotions (e.g., fear, anger, insecurity) and physiological responses (se.g., sweating, shaking, clenched fists) that the patient experiences in conjunction with this negative self-statement. Following this, the patient is instructed to choose a positive self-belief that is preferable, such as “I am strong and safe.” This positive statement should be rooted in truth and reflect what is happening in the present moment.5

Finally, the patient is prompted by the therapist to rate how true the positive statement is to the patient in the moment using a Validity of Cognition (VOC) scale of 1 (totally unbelievable) to 7 (totally believable).4 The patient is also asked to rate the negative belief and its associated physio-emotional impact using the Subjective Units of Disturbance (SUD) scale, ranging from 1 (no disturbance) to 10 (worst disturbance) scale (Figure 2).4

Composite Case Vignette 1 (continued)

During her second session, Miss M is able to vocalize her experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Though it takes some time and she is coached through a series of self-relaxation exercises, she manages to articulate the events that have led her to present for treatment. In the third session, the assessment phase begins.

Dr. A: As you focus on your experiences with COVID-19, what image or scene represents the worst part of it?

Miss M: Getting the phone call that my grandma was gone. We…[breaks off] we didn’t get to see her or say goodbye. We [through tears] couldn’t celebrate her life together. It was so fast, and my mom was just breaking down, and my dad was quiet, and I just…couldn’t feel anything. It’s like I was trapped in that horrible moment for months. I just kept seeing her there, dying alone without us, hooked up to all those tubes. And now, still being in that house where I learned she died, still not having moved forward [pauses]… I…it’s all a really freaking bad image, honestly.

Dr. A: Holding that image in your mind, what words would you use to describe your negative belief about yourself now?

Miss M: I – I don’t know. [Laughs] I guess that’s it. I don’t know anything. Lost. Useless. Inept. Disappointing. I’m useless, and I can’t do anything about it.

Dr. A: That’s normal, Miss M. You’ve been through a trauma. When that happens, it’s completely natural for the brain to stick to negative thought patterns. The thought loops you’re experiencing are your brain’s natural way of processing trauma. There’s nothing wrong with you. I know it may be frustrating, but it’s not permanent. With the exercises we’ll be doing, we’re going to work on retraining your brain to get out of these negative thought patterns.

Miss M: I…Thank you, Doctor, but it just seems so hard to believe right now.

Dr. A: And that’s OK. It’s OK for you to be hesitant to believe it, but even if you don’t believe it by now, the treatment will take its course. Your thoughts may be negative right now, but they will change.

Miss M: Honestly, I’m willing to try anything.

Dr. A: Let’s bring back that mental picture of the incident again. I want you to picture yourself on a train. Treat that memory as though it’s the scenery you’re watching from your window. It’s something you’re observing, not something you’re involved in. Like a movie. Just let it play out. [Pause] Now, when you think about it, what would you like to believe about yourself, even if it’s not something you necessarily believe right now?

Miss M: I…I don’t know. I guess I’d really like to believe that I’m doing my best right now, and that my feelings are valid. That my desire to be happy and carefree is valid. But that just does not feel true. I let the circumstances around me kick my ass, and now I can’t get back on my own two feet. It’s pathetic. I’m… I failed.

Dr. A: Humor me for a moment, Miss M. Even if you don’t believe the phrase, “I’m doing my best, and my feelings are valid,” is it something you would like to truly believe about yourself, if you could?

Miss M: I…I don’t deserve to believe my feelings are valid, Doctor.

Dr. A: Close your eyes, Miss M. [Miss M. closes her eyes.] Now, I’d like for you to focus on your breathing. Good. Now, I’m going to ask you again—and I don’t want you to tell me how you judge your response. I just want you to tell me how you feel when I say the following sentence. [Pauses for a moment] “I’m doing my best, and my feelings are valid.” [Another pause] Now, regardless of whether you believe you deserve to or not, is that something that you would like to believe about yourself?

Miss M: [Pause] Yeah. [Clears throat] Yeah, Doctor. I’d really like to be able to believe that.

Dr. A: Good, Miss M. Thank you. Now, I’m going to say that statement again. I’d like you to rate it on the VOC scale according to how much you believe it. [Pause] “I’m doing my best, and my feelings are valid.

Miss M: I…I have to give it a 1, Doctor.

Dr. A: As you listen to that statement and assess it, what emotions do you feel? There are no wrong answers here. Just express yourself however feels most honest.

Miss M: I just feel so- so…ashamed, I guess. Yeah. I hear that and I feel such shame, because… well, I feel like I really do deserve to feel…the shame.

Dr. A: OK. Thank you, Miss M. You’re doing just fine. I want you to do something now: close your eyes and hone in on that feeling of shame. What is the SUD for that emotion?

Miss M: It feels…heavy. Overwhelming. [Starts to breathe heavily.] Doctor, I don’t know if I can do this. This is so hard, I- I just feel so sad and helpless every time I think about it.

Dr. A: Go with that, Miss M

Miss M: I…it feels heavy. It feels like a 9 on that SUD scale.

Dr. A: You’re doing great, Miss M. Keep breathing at the same pace- go with that. Keep letting yourself feel your emotion. Can you feel it somewhere in your body? Does it feel like it’s taking a physical root somewhere?

Miss M: I- yeah. Yeah, I know exactly what you mean. I think about that statement, the positive one. And I just feel this…weight, this terrible heaviness – right here [points to sternum]. Like, right in the center of my chest, and the more I think about it, the more it radiates up, like a balloon, into my throat until I feel like I can’t speak.

Dr. A: Thank you, Miss M. I know that was difficult, but you did very well. You focused on your breathing and let yourself sit with your emotion. This is a safe space. You are in control. If, at any moment, you’d like to stop, we will stop. All right?

Miss M: Yes. Thank you.

Phase 4: Desensitization

This phase of the process homes in on the patient’s negative self-perceptions and ensuing responses.4 This is the phase during which the therapist will lead the patient in a series of sounds, taps, or eye movements until the patient experiences either two positive or two neutral responses to their targeted event. Once two positive or neutral responses are experienced, the therapist will ask the patient to give the memory another SUD rating. This will be done for the targeted event, as well as for any other associated disturbances that may arise over the course of treatment.5

Composite Case Vignette 1 (continued).

At this point, the therapist begins the Desensitization Phase, asking the patient to think of the incident, the negative self-assessment “I’m useless, and I can’t do anything about it”, and the body location. The patient is instructed to keep these in her mind while following your left-right hand movements with her eyes for a period of 30 seconds.

Dr. A: [At the end of the eye movements]. Okay, take a deep breath. Now, exhale and let it go. [Pause]. What do you notice now?

Miss M: I…I don’t know. I feel a little puzzled.

Dr. A: OK. Keep going with that. [Eye movements and silence.] Inhale – big, deep breath. Let it go. What do you feel now?”

[Note: The phrasing might be slightly different from this, and the therapist either keeps silent or provide minimal encouragement during the eye movements. This sequence repeats.22]

Miss M: My mom was just…weeping. Like I’ve never seen her before. And I didn’t even hug her. I just stood there, thinking about my grandma all alone without us and everything I lost in the last three weeks.

Dr. A: [Eye movements and silence.] What about now?

Miss M: I…I didn’t even want to hug my mom. Like, the thought didn’t register. [Through tears] It felt like something heavy and invisible was just sitting on my chest, and I couldn’t move.

Dr. A: [Eye movements and silence.] “That’s it, just feel that.”

Miss M: My parents were there for me. They couldn’t give me money, but they welcomed me home after I got evicted. And I was feeling sorry for myself the whole time, and I couldn’t even comfort my mom when she lost her mother without being able to say goodbye. I could barely even feel sad myself, at first. Then it… then I felt sad all the time. Ugh, and I feel so guilty about all of it.

Dr A: Miss M, now don’t stop following my movements with your eyes. Now, I want you to think back to the image you had in your mind at the beginning—of learning your grandma died. What SUD rating would you give it now?

Miss M: I… I guess it doesn’t… paralyze me as much as it did when I first thought about. I mean, it still sucks. I still feel the weight of it, but…maybe a 2?

Dr. A. Who determines the fate of an individual?

Miss M: I…I honestly don’t know.

Dr. A: But who doesn’t have a say?

Miss M: I know that I sure don’t.

A few sets of eye movements and responses follow, focusing on how it is not in Miss M’s power to prevent loved ones from dying, or to absorb others’ pain when tragedy occurs.

Phase 5: Installation

During this phase, the emphasis is placed on the positive belief that the patient has already decided upon.5 Once the negative self-belief has been reprocessed as an illusion, this positive belief is reaffirmed as the truth. The positive cognition (i.e. “I am strong and safe”) is introduced and emphasized until the patient manages to rate it at a 7 on the VOC scale, indicating that they have accepted and internalized it as true.

Composite Case Vignette 1 (continued)

Miss M: It’s ridiculous. That something like that could just come out of nowhere and throw my life out of whack – and take the life of someone I loved. That there was nothing I could do to help anyone – not my loved ones, not myself. It wasn’t in my power.

Dr. A: It wasn’t in your power to prevent what happened. We cannot prevent tragedies from happening; all we can do is our best to take care of ourselves. [Eye movements and silence.]

Miss M: I…I was doing my best to take care of myself. Even though I was numb. Day by day, I was getting up. Making breakfast. Looking for job posts. I was really trying to keep treading water, you know?

Dr. A: What would your grandmother tell you about how you’ve handled everything?

Miss M: She…she would tell me to celebrate the small victories. She would say that I can’t control the bad things that happen, and that it’s OK to be upset when they do. She would say that I can control my ability to rise above. [Pause] She would say, “this too shall pass, but only if you let it.”

Phase 6: Body Scan

Numerous studies have demonstrated that there is a strong correlation between unresolved negative thoughts and physiological responses.36,37 As a result, physical characteristics are monitored in order to help the therapist determine the extent to which a patient has successfully reprocessed their target event.

Once the installation stage has been completed, the patient is asked to think of the target event, and the therapist monitors them for physical signs of tension, distress, or discomfort.5 If any of these arise, they are specifically targeted for reprocessing through EMDR. This is done to ensure that the positive self-beliefs that were introduced have been adopted on both a physical and conceptual level.5

Composite Case Vignette 1 (continued)

Dr. A: OK, Miss M. Now I’d like you to think back to that first trigger memory, just like you did before. I’m going to give you a moment, and I’d like for you to just think about it.

While Miss M. takes a moment to think about the trigger image, Dr. A. monitors her for physical signs of distress. After a minute, she speaks.

Dr. A: How do you feel, Miss M.?

Miss M: I miss my grandmother. I’ll always miss her. But…I don’t feel that disturbance, that weight when I think about her in the hospital.

Dr. A: If you were to think about that phrase you articulated earlier – “I’m useless, and I can’t do anything about it” – do you feel that same heaviness in your chest?

Miss M: I…I honestly can’t believe I’m saying this. But that pressure in my chest? It’s not there. Not even when I think about it. I… this is unreal, but…I really don’t feel it.

Dr. A: And, how would you describe yourself, Miss M.?

Miss M: That I’m doing my best, and my feelings are valid. [Smiles.]

Phase 7: Closure

The purpose of every session is to leave the patient feeling better about their progress than they were before arriving at their appointment.5 This is particularly important when patients hit “roadblocks” or other obstacles during sessions that hinder their ability to reprocess a traumatic event. There are two types of closures: the first is a Completed Target Memory Session and the second is an Incomplete Target Memory Session.4 Incomplete sessions happen when a patient does not achieve two neutral or positive responses to the target event over the course of the session.5 In instances where this occurs, the therapist leads the patient through self-soothing relaxation exercises.3 The therapist will also equip the patient with coping mechanisms and exercises that will help them feel in control outside of sessions. Patients are also given insights into what to expect between sessions, documenting these experiences, and how to remain calm in stressful or triggering situations in everyday life.4

Composite Case Vignette 1 (continued)

Dr. A: Now, Miss M., you’ve done some great work here today. Now, if you should find yourself struggling in between sessions, let’s go over some breathing exercises and other activities that will help you remain calm.

Dr. A. and Miss M review some self-soothing practices.

Miss M: Thank you, Doctor. Having these at my disposal feels really good. I just… I feel so grateful. To you, to my family members who have helped me through everything. Even to myself, for plucking up the courage to come and see you.

Phase 8: Re-evaluation

Every new session begins with re-evaluation, during which time the therapist reviews the client’s current emotional and psychological state, their responsiveness to treatment and self-relaxation techniques, and any memories or thoughts that have arisen since the last session.5 The therapist works alongside the patient to determine what new techniques or treatments might be needed to address the issues they’re experiencing.

Composite Case Vignette 1 (continued).

After the patient expresses that she feels okay, and grateful for her support system, the session (Phase 7) is closed, and you ask the Patient about her experience with the session.

Dr. A: Is there anything you learned or would like to talk about after today’s session?

Miss M: [Through tears] I didn’t know this was possible. I… that pressure I was talking about before? It feels…so much lighter. I feel less…weighed down? Yeah…less heavy. I’m not [gestures, makes quotation symbols with hands] “a new person” or anything – but I am…like, really am, able to see things differently. It’s…not something I expected..

Conventional Patients Who Would Benefit from EMDR

EMDR is particularly effective for individuals with PTSD, as demonstrated by a 2019 study of 47 patients suffering from PTSD that found after EMDR (with a median of four EMDR sessions), 40 percent of participants scored below the threshold required for a PTSD diagnosis.38 Another study conducted in 2018, used two meta-analyses and four randomized-controlled trials to assess the effectiveness of EMDR. Its findings were that, regardless of patients’ cultural backgrounds, EMDR was more effective than other trauma treatments in improving PTSD diagnosis, reducing PTSD symptoms, and mitigating other trauma-related symptoms.39

Of 10 studies conducted on EMDR therapy, seven found it to be a faster and more effective treatment of PTSD than trauma-focused CBT.1 Similarly, 24 randomized controlled trials report that EMDR therapy has a positive effect on the treatment of emotional trauma and other traumatic life experiences.1 12 randomized assessments of the eye movement component documented significant decreases in negative emotionality and vividness of troubling images during EMDR.1 Another analysis of 26 randomized EMDR therapy trials for PTSD, all published between 1991 and 2013, found that EMDR has a significant impact on decreasing the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD.40

Similar Treatments

Previous studies have focused on additional conventional therapies using memory reconstruction. Life review therapy is a memory reconstruction technique used in elderly and terminally ill patients where patients gradually evaluate their autobiographic memory and learn to come to terms with their past life. This technique leads to decreased depressive feelings and improves spiritual and psychosocial well-being.41 Decreased autobiographical memory recall is a common finding in patients with depression. Memory specificity training is a memory reconstruction technique that has been shown to improve recall of positive memories in patients who were depressed.42 Additionally, a technique called the multi-model memory restructuring (3MR) system has shown benefit in treating patients with PTSD. The 3MR system has patients create a timeline of their memories and use a diary to add visuals and text referencing the memories. A three-dimensional version of the memory is then created, and the patient is treated with an exposure approach.43

Other Potential Uses of EMDR

The strong positive correlation between EMDR and the mitigation of PTSD symptoms signifies promising possibilities for other psychiatric conditions. In fact, initial evidence suggests that EMDR could be an effective measure to treat trauma-related symptoms among patients suffering from comorbid psychiatric disorders. There is also research indicating that EMDR could have positive results in treating trauma affective symptoms in patient with chronic pain, bipolar disorder, depression, substance use disorders, and intellectual disabilities.44

Bipolar Disorder. Though there are not many studies examining the impact of EMDR treatment on patients with bipolar disorder, EMDR has a strong positive impact on the amelioration of trauma affective symptoms, indicating that those struggling with bipolar disorder and PTSD might stand to benefit from EMDR methods.45 Specifically, EMDR has shown benefit in preventing relapse and treating trauma affective symptoms in patients with bipolar disorder as well as increasing treatment compliance and patient’s disease awareness.45

Depression and generalized anxiety disorder. In a study conducted by Wood et al, eight patients suffering from depression were exposed to EMDR. Of these, seven experienced clinically significant improvement on the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression46 EMDR when combined with Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) results in a lower number of remissions and additional benefit in patients with depression based on post-treatment Beck Depression Inventory II scores.47 Similarly, in patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), EMDR improved patients’ tolerance to uncertainty and allowed them to overcome their cognitive avoidance. Additionally, these factors continued to decline after one month of treatment.48

Substance use disorders. In patients with substance use disorder, EMDR has the potential to create a safe environment for patients to access their emotions and shift their perspective to implement lifestyle changes.49 In a study exploring EMDR as an add-on treatment among patients with substance use disorders, those who received EMDR in addition to their usual treatment showed a significant improvement in PTSD and dissociation symptoms, as well as a reduction in general anxiety. Those who received their usual treatment without an EMDR add-on only experienced a clinically significant reduction in PTSD symptoms.50

Intellectual disabilities. Success has also been shown in EMDR treating patients who are intellectually disabled and with a history of trauma.51 Karatzias et al conducted a study with 29 adults with PTSD and intellectual disabilities and found that 60 percent of participants who received EMDR in addition to standard care were diagnosis-free at the end of treatment. At a three-month follow-up, 43 percent of patients were still diagnosis-free.52

Limitations and Negative Side-effects of EMDR

Though studies related to the efficacy of EMDR reveal promising results, they generally test small sample sizes of patients. EMDR is a relatively new phenomenon and, as such, still poses many questions regarding its long-term efficacy.

Some critiques of EMDR assert that it requires too many sessions in order to yield results, which could prove to become a financial obstacle for patients.53 Some authors posit that, just as eye movements and recall render negative memories less unpleasant, they could just as easily render positive memories less pleasant.53,54

In addition, some ethical questions have arisen as a response to EMDR, related to whether it is ethically sound to experiment with patients’ re-exposure to their triggers and psychological traumas. Shapiro asserts that, if EMDR is not used appropriately, patients might be retraumatized or even left immobilized.7 Ultimately, it is the responsibility of EMDR practitioners to adhere to the eight outlined steps of the process, mindfully adapting their practice to the needs of each patient.

EMDR is effective for individuals with traumatic pasts by decreasing the associated distress associated with their disruptive memory.30 However, in a forensic setting, a witness’s statement could be disrupted due to their reconstructed memory.55 Additionally, many EMDR studies are measured by subjective measures and could be strengthened by including behavioral measures like improved sleep patterns and social validation procedures like ratings by significant others.56 The mean effect size for EMDR (d=.90) reported by Wilson et al is equal to the mean effect size reported in a meta-analysis conducted by Otto, Penava, Pollock, and Smoller57 of non-EMDR exposure treatments for PTSD.56 Individuals can be susceptible to false memories. A study conducted by Houben et al found that a majority of surveyed EMDR practitioners endorsed the idea of repressed memories.55 Therefore, EMDR practitioners must be careful when suggesting the possibility of repressed memories particularly in those with vague memories.

Some critics argue that EMDR contains many similarities to other forms of trauma-focused psychotherapy and exposure techniques.58,59 These critics contend that the bilateral stimulation associated with EMDR is not an essential component, as Shapiro has asserted.8 A meta-analysis conducted by Seidler and Wagner compared the efficacy of EMDR to trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of PTSD.60 This meta-analysis included seven studies and determined that neither form of treatment was found to be superior in efficacy. However, Lee and Cuijpers conducted another meta-analysis with 15 clinical trials and compared traditional EMDR to EMDR without accompanying eye movements.61 The results of this meta-analysis indicate that the effect size for eye movements in a therapy context was moderate and significant. Although controversy related to the bilateral stimulation persists40 and more research is needed to elucidate its mechanism of action,62 EMDR remains an effective psychotherapy for PTSD.63

Conclusion

EMDR is an effective method by which to mitigate PTSD symptoms, empowering individuals to redefine their relationship to their trauma and move forward with an improved quality of life. Other types of psychotherapy focus on directly altering the emotions, thoughts and reactions resulting from previous traumatic experiences, but EMDR therapy focuses directly on the memory. By changing the way that the memory is stored in the brain, the emotions associated with the memory become less intense throughout the course of the therapy. Since EMDR is still in its early stages of study and implementation, it is imperative that more studies be conducted with large sample sizes and other psychiatric conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wendy Doolittle, PCC-S, LISW, LICDC-CS. and Susanne Mackenzie, LPCC-S for their review of the manuscript and guidance related to EMDR therapy techniques.

References

- Shapiro F. The role of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) therapy in medicine: addressing the psychological and physical symptoms stemming from adverse life experiences. Perm J. 2014;18(1):71-77.

- EMDR Institute, Inc site. What is EMDR? http://www.emdr.com/what-is-emdr/.Accessed 15 May 2020.

- American Psychological Association site. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy. https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/treatments/eye-movement-reprocessing. Accessed 3 Jul 2020.

- Hensley BJ. An EMDR Therapy Primer: From Practicum to Practice. Second edition. Springer Publishing Company; 2016.

- Leeds AM. A Guide to the Standard EMDR Protocols for Clinicians, Supervisors, and Consultants. Springer Publishing Company; 2009.

- Cuijpers P, Veen SC va., Sijbrandij M, Yoder W, Cristea IA. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing for mental health problems: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cogn Behav Ther. 2020;49(3):165-180.

- Shapiro F. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing: Basic Principles, Protocols, and Procedures. Guilford Press; 1995.

- Shapiro F. Efficacy of the eye movement desensitization procedure in the treatment of traumatic memories. J Trauma Stress. 1989;2(2):199-223.

- Gunter RW, Bodner GE. How eye movements affect unpleasant memories: Support for a working-memory account. Behav Res Ther. 2008;46(8):913-931.

- Nieuwenhuis S, Elzinga BM, Ras PH, et al. Bilateral saccadic eye movements and tactile stimulation, but not auditory stimulation, enhance memory retrieval. Brain Cogn. 2013;81(1):52-56.

- Lanius UF, Paulsen SL, Corrigan FM. Neurobiology and Treatment of Traumatic Dissociation: Toward an Embodied Self. Springer Publishing Company; 2014

- Gunter RW, Bodner GE. EMDR works . . . but how? Recent progress in the search for treatment mechanisms. J EMDR Pract Res. 2009;3(3):161-168.

- Baddeley A. Working memory. Science (80- ). 1992;255(5044):556-559.

- Baddeley AD. Human Memory: Theory and Practice. Allyn and Bacon; 1990.

- Keane, T.M., Zimering, R.T., Caddell JM. A behavioral formulation of postraumatic stress disorder in Vietnam veterans. Behav Ther. 1985;8(1):9-12.

- Stampfl TG, Levis DJ. Essentials of implosive therapy: a learning-theory-based psychodynamic behavioral therapy. J Abnorm Psychol. 1967;72(6):496-503.

- Wolpe J. Psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition. Stanford Univ Press;1958.

- Carlson JG, Chemtob CM, Rusnak K, Hedlund NL, Muraoka MY. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) treatment for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 1998;11(1):3-24.

- Van Etten ML, Taylor S. Comparative efficacy of treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Psychother. 1998;5(3):126-144.

- Edmond, T., Rubin, A., Wambach KG. The effectiveness of EMDR with adult female survivors of childhood sexual abuse. Soc Work Res. 1999;23(2):103-116.

- Ironson G, Freund B, Strauss JL, Williams J. Comparison of two treatments for traumatic stress: A community-based study of EMDR and prolonged exposure. J Clin Psychol. 2002;58(1):113-128.

- Fernandez, I., Gallinari, E., Lorenzetti A. A school-based intervention for children who witnessed the Pirelli Building airplane crash in Milan, Italy. J Br Ther. 2004;2:129-136.

- Konuk, E., Knipe, J., Eke, I., Yuksek, H., Yurtserver, A., Ostep S. The effects of EMDR therapy on post-traumatic stress disorder in survivors of the 1999 Marmara, Turkey earthquake. Int J Stress Manag. 2006;13:291-308.

- Jarero I, Artigas L, Hartung J. EMDR integrative group treatment protocol: A postdisaster trauma intervention for children and adults. Traumatology (Tallahass Fla). 2006;12(2):121-129.

- Gil-Jardiné C, Evrard G, Al Joboory S, et al. Emergency room intervention to prevent post concussion-like symptoms and post-traumatic stress disorder. A pilot randomized controlled study of a brief eye movement desensitization and reprocessing intervention versus reassurance or usual care. J Psychiatr Res. 2018;103:229-236.

- Proudlock S, Peris J. Using EMDR therapy with patients in an acute mental health crisis. BMC Psychiatry. 2020;20(1):1-9.

- Jarero I, Givaudan M, Osorio A. Randomized controlled trial on the provision of the EMDR Integrative Group Treatment Protocol adapted for ongoing traumatic stress to female patients with cancer-related posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. J EMDR Pract Res. 2018;12(3):94-104.

- Hurley EC. Effective treatment of veterans with PTSD: Comparison between intensive daily and weekly EMDR approaches. Front Psychol. 2018;9(AUG):1458.

- Bossini L, Santarnecchi E, Casolaro I, et al. Morphovolumetric changes after EMDR treatment in drug-naïve PTSD patients. Riv Psichiatr. 2017;52(1):24-31.

- Santarnecchi E, Bossini L, Vatti G, et al. Psychological and brain connectivity changes following trauma-focused CBT and EMDR treatment in single-episode PTSD patients. Front Psychol. 2019;10(FEB):1-17.

- Kroes MCW, Whalley MG, Rugg MD, Brewin CR. Association between flashbacks and structural brain abnormalities in posttraumatic stress disorder. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(8):525-531.

- Propper RE, Christman SD. Interhemispheric interaction and saccadic horizontal eye movementsImplications for episodic memory, EMDR, and PTSD. J EMDR Pract Res. 2008;2(4):269-281.

- Christman SD, Garvey KJ, Propper RE, Phaneuf KA. Bilateral eye movements enhance the retrieval of episodic memories. Neuropsychology. 2003;17(2):221-229.

- EMDR International Association site. EMDR Therapy. https://www.emdria.org/about-emdr-therapy/experiencing-emdr-therapy/Accessed 16 May 2020.

- van den Hout MA, Engelhard IM. How does EMDR work? J Exp Psychopathol. 2012;3(5):724-738.

- Pace-Schott EF, Amole MC, Aue T, et al. Physiological feelings. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;103:267-304.

- Purves D, Augustine GJ, Fitzpatrick D, Hall WC, LaMantia A-S, White LE. Physiological Changes Associated with Emotion – Neuroscience. 2001. NCBI Bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK10829/. Accessed 20 May 2020.

- Slotema CW, van den Berg DPG, Driessen A, Wilhelmus B, Franken IHA. Feasibility of EMDR for posttraumatic stress disorder in patients with personality disorders: a pilot study. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2019;10(1):1614822.

- Wilson G, Farrell D, Barron I, Hutchins J, Whybrow D, Kiernan MD. The use of Eye-Movement Desensitization Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy in treating post-traumatic stress disorder-A systematic narrative review. Front Psychol. 2018;9(JUN):923.

- Chen YR, Hung KW, Tsai JC, et al. Efficacy of eye-movement desensitization and reprocessing for patients with posttraumatic-stress disorder: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2014;9(8).

- Kleijn G, Lissenberg-Witte BI, Bohlmeijer ET, et al. The efficacy of Life Review Therapy combined with Memory Specificity Training (LRT-MST) targeting cancer patients in palliative care: A randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2018;13(5):1-13.

- Neshat-Doost HT, Dalgleish T, Yule W, et al. Enhancing autobiographical memory specificity through cognitive training: An intervention for depression translated from basic science. Clin Psychol Sci. 2013;1(1):84-92.

- Tielman ML, Neerincx MA, Bidarra R, Kybartas B, Brinkman WP. A therapy system for Post-traumatic Stress Disorder using a virtual agent and virtual storytelling to reconstruct traumatic memories. J Med Syst. 2017;41(8).

- Valiente-Gómez A, Moreno-Alcázar A, Treen D, et al. EMDR beyond PTSD: A systematic literature review. Front Psychol. 2017;8(SEP):1-10.

- Bedeschi L. EMDR Protocol for Bipolar Disorders. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2018;3:222-225.

- Wood E, Ricketts T, Parry G. EMDR as a treatment for long-term depression: A feasibility study. Psychol Psychother Theory, Res Pract. 2018;91(1):63-78.

- Hofmann A, Hilgers A, Lehnung M, et al. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing as an adjunctive treatment of unipolar depression: A controlled study. J EMDR Pract Res. 2015;9(3):E94-E104.

- Farima R, Dowlatabadi S, Behzadi S. The effectiveness of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) in reducing pathological worry in patients with generalized anxiety disorder: A preliminary study. Arch Psychiatry Psychother. 2015;17(1):33-43.

- Marich J. Eye Movement Desensitization and reprocessing in addiction continuing care: A phenomenological study of women in recovery. Psychol Addict Behav. 2010;24(3):498-507.

- Carletto S, Oliva F, Barnato M, et al. EMDR as add-on treatment for psychiatric and traumatic symptoms in patients with substance use disorder. Front Psychol. 2018;8(JAN):1-8.

- Barol BI, Seubert A. Stepping Stones: EMDR treatment of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities and challenging behavior. J EMDR Pract Res. 2010;4(4):156-169.

- Karatzias T, Brown M, Taggart L, et al. A mixed-methods, randomized controlled feasibility trial of Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) plus Standard Care (SC) versus SC alone for DSM-5 Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in adults with intellectual disabilities. J Appl Res Intellect Disabil. 2019;32(4):806-818.

- Van Den Hout M, Muris P, Salemink E, Kindt M. Autobiographical memories become less vivid and emotional after eye movements. Br J Clin Psychol. 2001;40(2):121-130.

- Engelhard I, van Uijen S, van den Hout M. The impact of taxing working memory on negative and positive memories. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2010;1(1):5623.

- Houben, S.T.L., Otgaar, H., Roelofs, J., Wessel, I., Patihis, L., Merckelbach H. Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) practitioners’ beliefs about memory. Psychol Conscious Theroy, Res Pract. 2019.

- Lohr JM, Tolin DF, Lilienfeld SO. Efficacy of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: Implications for behavior therapy. Behav Ther. 1998;29(1):123-156.

- Otto, M.W., Penava, S.J., Pollock, R.A., Smoller JW. Cognitive-behavioral and pharmacologic perspectives on the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. In: Challenges in Clinical Practice: Pharmacologic and Psychosocial Strategies. 1996:219-260.

- Schubert S, Lee CW. Adult PTSD and its Treatment with EMDR: A review of controversies, evidence, and theoretical knowledge. J EMDR Pract Res. 2009;3(3):117-132.

- Jeffries FW, Davis P. What is the role of eye movements in eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)? A review. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2013;41(3):290-300.

- Seidler GH, Wagner FE. Comparing the efficacy of EMDR and trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy in the treatment of PTSD: A meta-analytic study. Psychol Med. 2006;36(11):1515-1522.

- Lee CW, Cuijpers P. A meta-analysis of the contribution of eye movements in processing emotional memories. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 2013;44(2):231-239.

- Nowill J. A critical review of the controversy surrounding eye movement desensitization and reprocessing. Couns Psychol Rev. 2010;25(1):63-70.

- Oren E, Solomon R. EMDR therapy: An overview of its development and mechanisms of action. Rev Eur Psychol Appl. 2012;62(4):197-203.

- Thrive Therapy Houston site. Counseling, Therapy and Mental Health Services for Adult, Children, and Families Trauma, Depression, Anxiety, Self-Harm, Abuse, Attachment Behavior Play Therapy. 2020. Clinician’s Corner. http://www.thrivetherapyhouston.com/clinicians-corner/. Accessed 3 Jul 2020.

- Dudley and Walsall site. EMDR Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing Therapy. 2015. www.dwmh.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/P13-EMDR.pdf. Accessed 3 Jul 2020.