by Nolan Carlile, DO; Jared S. Link, PsyD; Allison Cowan, MD; and Elizabeth G. Sarnoski, MD

Drs. Carlile, Cowan, and Sarnoski are with Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. Drs. Carlile, Sarnoski, and Link are with the U.S. Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, Ohio.

Funding: No funding was provided.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Department editors: Julie P. Gentile, MD, is a professor with and chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio.

Editor’s Note: The patient cases presented in Psychotherapy Rounds are composite cases written to illustrate certain diagnostic characteristics and to instruct on treatment techniques. The composite cases are not real patients in treatment. Any resemblance to a real patient is purely coincidental.

Abstract: Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), a form of cognitive behavioral therapy, predominately focuses on addressing one’s relationship with thoughts and emotions rather than attempting to alter them. The use of ACT has demonstrated efficacy in interactions with patients suffering from a variety of mental health concerns. While there are no specific criteria for the use of ACT, one compelling argument that exists in support of its use is that ACT may be more efficacious than other control-based protocols in treating experiential avoidance. Further, there is some evidence available to suggest that ACT is more effective than other active treatments for depression. Here, the six core processes of ACT therapy are discussed and the application of ACT techniques in clinical practice is explored.

Keywords: ACT therapy, ACT psychotherapy, acceptance, defusion, values

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2019;16(9–10):17–21

Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) is considered a “third-wave” cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) approach that predominately focuses on addressing one’s relationship with thoughts and emotions rather than attempting to change them.1 Other forms of third-wave CBT include dialectical behavioral therapy2 and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.3 The latter is rooted in mindfulness-based stress reduction, a treatment for a multitude of psychiatric and medical conditions.4 Many published studies support the efficacy and effectiveness of ACT therapy.5 Even more has been written to instruct providers and patients in the use of this approach to therapy. Here, we provide an informative introduction to the core concepts and processes of ACT to stimulate further exploration of the available literature.

Concept

ACT is a form of CBT that comes from contextual behavioral science and, as of February 2019, more than 280 randomized controlled studies have been organized to explore the effectiveness of ACT.6 The idea that thoughts are simply words driven by contextual factors is the central concept of the ACT paradigm. In some individuals, certain thought-driven words foster suffering and psychological inflexibility; however, through the ACT paradigm, an individual is encouraged to focus on living a valued, meaningful life, thereby reducing suffering and increasing mental flexibility. Consider the following concept: day in and day out, the mind consistently feeds an individual stories about themselves and the world. Regardless of their veracity, if certain thoughts or stories cause pain to the individual, that individual will likely react in ways to avoid the pain. These very efforts to avoid pain can prevent the individual from living the life he or she wants to live, and suffering persists as a result. Life can be epitomized by emotional and physical pain for some individuals. The ACT paradigm can help the patient shift his or her focus from painful thoughts to nonjudgmental acceptance of the inner experience, being present, and living in accordance with his or her values, with the goals of reducing suffering and increasing meaningful living.

Patient selection for ACT

The use of ACT has demonstrated efficacy in interactions with patients suffering from a variety of mental health concerns.7 In treating depression and certain physical health disorders, ACT has also been shown to be effective in reducing symptoms.8 ACT has also been successfully applied to improve symptoms of social impairment and distress associated with hallucinations in inpatient psychiatric patients with psychotic symptoms.9 Using ACT for anxiety and depression resulted in improvements in symptoms of depression and anxiety, functioning difficulties, quality of life, and life satisfaction.10 There is also evidence for its use in other disorders, such as social anxiety disorder, trichotillomania, chronic pain, and eating disorders.11–14 While there are no specific criteria for the use of ACT, one compelling argument supporting its application is its superior efficacy compared to other control-based protocols in treating experiential avoidance, a key symptom in many psychological disorders.15,16 There is some evidence that ACT is more effective than other active treatments for depression, such as CBT; however, further research is needed.17

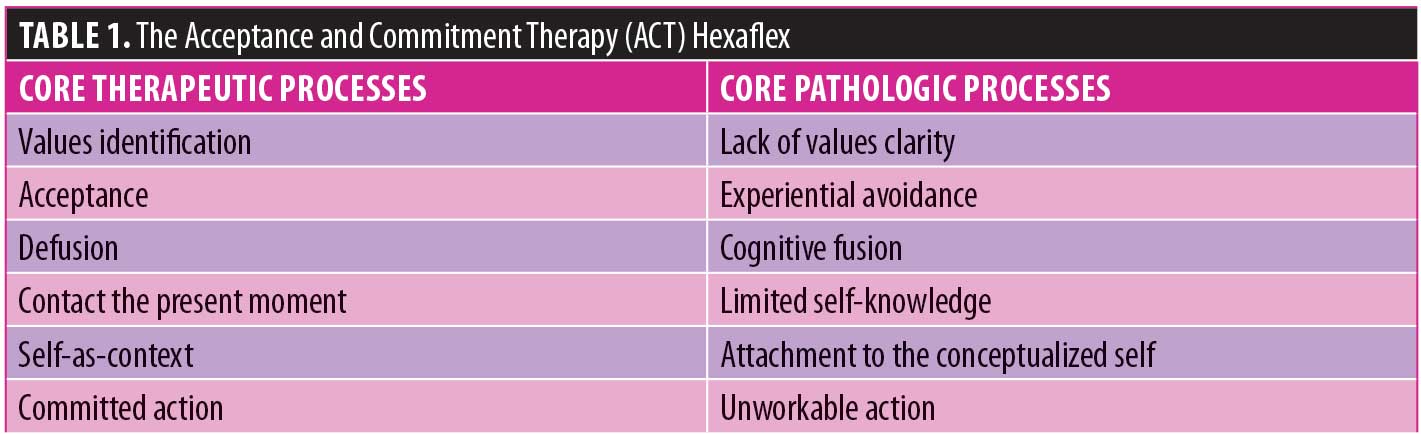

The six core processes of ACT therapy are identification, acceptance, defusion, contact with the present moment, self-as-context, and committed action. These processes help the patient and provider address corresponding core problems often described as lack of values clarity, experiential avoidance, cognitive fusion, limited self-knowledge, attachment to conceptualized self, and unworkable action.18 These therapeutic processes are often referred to collectively as the ACT Hexaflex as they are interrelated with and interdependent on one another.19 ACT relies heavily on the use of metaphors and experiential exercises to help the patient better understand and apply the concepts contained within the ACT Hexaflex (Table 1).20

Values

People who are suffering from mental illness can lose touch with what is most important to them. ACT demands that the patient take time to identify, connect with, and prioritize personally held values. Values are statements about ideas most important to the individual. They are the guiding principles of action or ways of living. Just as one can be ever-traveling in a westward direction, one can also be ever-living a life guided by values.19 Using ACT’s strong use of metaphor, value-driven goals can be viewed as landmarks passed along the way. Examples of values include maintaining good physical health, feeling connected to a life partner, or being a reliable employee. Corresponding value-driven goals might include running a marathon, taking a partner on a once-in-a-lifetime vacation, or efficiently finishing a project at work.

A crucial task of the ACT therapist is to help patients identify and clarify values. For some patients, it might only require a brief reminder to re-establish contact with their values. For others, such an effort might be quite challenging, requiring multiple sessions of careful and empathic discussion. Simple interventions might include encouraging the patient to actively consider values in different domains of his or her life by utilizing prepared worksheets. One experiential exercise involves asking the patient to imagine all of his or her loved ones attending the patient’s imagined 85th birthday and then to describe what he or she hopes those people would say about the patient, his or her character, and the way he or she lived life.

One willing but very anxious patient, upon being given a values identification assignment blurted out, “I don’t think I can do that.” Despite this instance of cognitive fusion (discussed later) and following some encouragement, he did ultimately complete the assignment. What he discovered about himself and the things most important to him (i.e., providing emotionally for the needs of his wife and daughter) resulted in a major turning point in treatment. With the guiding direction of being in touch with his most important values, his behavior began to change in productive ways; previously difficult decisions became simpler to make. He developed a keen sense of fulfillment doing things that were consistent with his most important values.

Values are fluid and can change in content or priority over time. Additionally, multiple values can demand opposing behaviors, which will create internal conflict. Consider a parent with young children who values both the role he or she plays in raising the children and his or her professional advancement. Values-guided action might require some sacrifice in one or both realms. Over time, as the children grow and their needs change, the value-guided actions of the parent might also change. The ACT therapist actively works with patients to help process and make decisions about how to deal with such conflicts. With a firm understanding of the importance of values in guiding behavior, the barriers that often keep patients from acting according to their values must be addressed.

Acceptance versus Experiential Avoidance

It is human nature to be repelled by pain and to strive for happiness and comfort; however, it is true that painful, difficult emotions and experiences are also a normal and expected part of the human existence. When a person struggles with some aspect of his or her current situation, that person can become stuck or feel hopeless, doing all he or she can to make the pain go away or to mask the pain. Experiential avoidance is a term used to describe a person’s efforts to avoid, resist, or mask difficult experiences associated with pain.21 All humans engage in experiential avoidance at varying levels of frequency and intensity. When experiential avoidance results in missed opportunities to live the valued life or causes one to engage in harmful behaviors, such as substance abuse, the result is suffering. The goal of acceptance is to help patients develop the ability to mindfully allow these inevitable and difficult experiences to occur. Often, it is the painful experiences that help one know what is most important to them. Sadness in the context of being separated from a loved one reminds one of just how important that person is to them. Once a patient is willing to compassionately accept the current situation as well as the accompanying thoughts and emotions without judgment, he or she can direct focus and energy toward living a rich, meaningful life that is consistent with his or her values. A helpful technique that fosters acceptance is to ask the patient directly, “Can you feel this way and still do what is most important to you?”

Defusion

Cognitive fusion is another significant source of suffering. This term describes a person’s tendency to over-identify with or to place high emotional valence on thoughts that come to mind. Some psychotherapy patients get caught up in attempts to evaluate, problem-solve, compare, or avoid. This has the potential to draw a person away from his or her actual lived experience.22 The identification of unhelpful thoughts is a common feature of all cognitive therapies. ACT differs in that there is no attempt to challenge or replace these thoughts. Rather, the provider will help the patient learn to unhook or defuse from such cognitions or emotions. In other words, the patient learns to stop struggling with his or her thoughts and to establish some distance from the distressing internal dialogue. This is done so as to observe the situation within its context versus being wrapped up in the content. For example, an author sat down to write and thought, “Who am I to think I have anything to say that others will find meaningful?” While the topic on which she was writing was both interesting and important to her, those thoughts were ultimately unhelpful. It would have been easy for the author to fuse with such a thought, to believe that because she had the thought it must be true. Cognitive fusion might have kept the author from writing altogether.

There are many strategies ACT providers have used to help patients unhook or defuse from their thoughts and emotions. A very simple but effective technique to gain some distance from a thought is to repeat it with the preface “I notice I am having the thought…” This can be followed by “I notice I am having the emotion … because I am having the thought…” The patient has now moved from being wrapped up with the thought to observing it from a distance and in context. This and many more strategies are easily found in ACT resources. Ideally, the patient will, with the help of the therapist, adapt or develop his or her effective methods.20 Such an exercise will be a challenge for most patients because it requires them to slow down and observe their own inner experiences, which leads to the next point on the ACT Hexaflex.

Contact with the Present Moment

It is necessary and useful to plan for the future and learn from the past. Unfortunately, psychotherapy patients often spend time stuck in one or both of these domains. Anxiety often involves an overwhelming focus on and worry about the future or rumination on previous actions. Depression might contain a similar overemphasis on the regrets of the past or a loss of hope for the future. An excessive amount of mental energy focusing on the past and future effectively robs the individual of the ability to be fully present in the here and now. The vehicle that allows one to defuse from painful thoughts and to contact the current moment is mindfulness. Mindfulness, as defined by Williams and Kabat-Zinn in 2013, involves paying attention to the present moment, not judging what is happening, and accepting what thoughts and feelings occur within the person as a result of any given situation.23 Acceptance, defusion, and the ability to be in contact with the present moment are all interdependent.

Consider the case of a 60-year-old patient diagnosed with persistent depressive disorder, who presented for treatment stating “I cannot feel joy.” After significant work clarifying values and learning acceptance and defusion, he began to notice his baseline mood improving. In Session 15, he reported, “Last Saturday night, I felt happy.” He had been attending a meeting at his church. He had consistently found his time and service efforts at church fulfilling but had failed to experience significant pleasure or joy in these activities. By processing his experience, it came to be understood that he had been fully present. For the first time, he was not preoccupied with painful or difficult thoughts while at church. Due to his present moment awareness, he was able to reap the emotional benefit of his committed action.

Mindful breathing as well as a variety of structured mindfulness exercises are commonly used to achieve awareness of the present moment.24 Patients can be encouraged to practice making contact with the present moment even while engaging in everyday tasks. Some suggestions include mindful walking and mindfully listening to music.19 Mindful walking is simply attending to different environmental stimuli surrounding the patient, such as the sound of walking on snow, leaves, or cement; birds chirping; and/or wind chimes. The patient will strive to notice the different muscles involved with the act of walking, noticing the difference between walking on grass versus pavement, observing the discolorations of the sidewalk or the grass, trees, sunshine, or rain. A truly unique experience is possible every time one starts walking, even if on a well-worn path.

Self-as-context

Self-as-context is an important concept within the ACT paradigm that patients and providers might find challenging to comprehend. Self-as-context is the psychological space from which one observes his or her thoughts and emotions as they occur. Interestingly, if the patient can observe his or her thoughts and emotions, then they cannot be his or her thoughts and emotions.19 ACT providers frequently help patients draw the distinction between the “thinking self,” which contains all one’s thoughts, facts, judgments, emotions, and so on, and the “observing self,” which mindfully notices these as they come.19 The thinking self is acting out all the different emotions and thoughts that can occur. Many people spend most if not all of their time on the stage. When one is able to access the observing self, however, he or she can mindfully witness what happens from the seats. Once the patient recognizes that he or she is not defined by his or her emotions and thoughts, the patient is empowered to mindfully accept, defuse, and move forward in a value-driven way.

According to Stoddard and Afari, it can be helpful to consider the observing self as the sky and one’s thoughts and emotions as the weather. While the weather will be ever-changing and, at times, can rage, the sky never changes.19 Moreover, the sky, which is the context within which the weather occurs, cannot be damaged or harmed by the weather. When the clouds obscure the sky, though unseen, the sky remains, unchanging.19

The discussion of self-as-context with a patient should not be isolated to one or two sessions. It should be incorporated into every session and can be highlighted in overt and covert ways. A frank discussion with the patient regarding “tapping” into this part of themselves is often helpful. The provider will make deliberate attempts to bring to light the part of the patient that is unchangeable. By doing so, the provider is fostering openness and acceptance and, thus, less suffering.

Committed Action

With a better understanding of the importance of values, mindfully noticing thoughts and emotions, and the use of acceptance and defusion, the final point of the ACT Hexaflex is committed action. While this discussion has focused thus far on cognition, ACT places great emphasis on the behavioral components of treatment. The key to effective action is letting values be the guide. The provider will help the patient identify and acknowledge any experiential avoidance and work out whether such strategies are workable. In other words, do they lead the patient toward a rich and fulfilling life or prevent that in the interest of momentarily reducing discomfort?23 Once the patient has decided to take committed action, the provider can help by using behavioral interventions, such as goal-setting, conducting behavioral experiments, or discussing problem-solving scenarios.24

Using ACT Techniques During Psychiatric Medication Management Visits

ACT techniques can be effectively utilized by the psychiatrist whose practice is generally restricted to brief and infrequent medication management appointments. With the aim of helping patients experience reduced suffering, the psychiatrist will first develop an empathic understanding of the patient’s condition from a biopsychosocial perspective. The psychiatrist can empathize and help the patient clarify what is most important to them. In subsequent visits, these values can be reiterated to help the patient continue to act upon them in their given circumstances.

Most psychiatrists can empathize with a patient who struggles within their current psychosocial situation. Often, a patient is unable or not yet ready to change his or her circumstances. This inevitably impacts a patient’s recovery regardless of the medication chosen. In these situations, helping patients develop acceptance can have a significant positive impact. Metaphors are often effective tools to accomplish this. One effective metaphor involves asking the patient to imagine treading water. The patient is exerting a significant amount of energy but often feel stuck and, despite his or her efforts, is no closer to valued living or a sense of mental well-being. The patient is suffering. The psychiatrist may suggest two options to reduce this suffering. Again using the richness of metaphor in ACT, propose 1) to mindfully practice acceptance in the patient’s current life circumstances and learn to float in place or 2) to swim in the direction of a personally held value. The first is helpful if the patient is already actively living according to his or her values. For example, if the patient has decided that devoting more time to care for a young child is of higher value than focusing on career gains, it would be important to compassionately accept his or her emotional experience of both the joy of shared time with family and the pain of missed career opportunities. Regarding the second option, which involves swimming toward a value-driven goal, if the patient decided that the more values-based decision would be to actively pursue a career opportunity, a plan could be created to assist with childcare. Use of ACT-based metaphors like this are easily employed andcan help patients gain new perspectives and accept their thoughts and emotions more readily.

The use of behavioral experiments can also assist in transitioning patients toward valued living, even when these actions are accompanied by difficult emotions. A patient might be asked to hold his or her breath for as long as possible while the provider takes note of the time. After the initial effort, the provider coaches the patient. Using mindfulness, defusion, and acceptance, the patient can gain some distance from the feared experience of being out of breath. The patient might learn to thank the mind and body for the drive to breathe and thus view the discomfort from a different, more grateful perspective. The patient can be instructed to scan the body for feelings of discomfort and simply observe its reaction to the need to breathe. From the observing mind, the patient can practice increasing and reducing the awareness of the physical demand to breathe. The patient will then repeat the experiment with the new skills. Invariably, the patient will hold his or her breath longer the second time, using the techniques gained. The thoughts that accompanied this exercise can be mined to demonstrate the way that one’s thoughts might impact one’s behavior—for example, trying to convince the patient that he or she must breathe sooner than is physiologically necessary or he or she could “die” or “have a panic attack.” These observations can be generalized to more daily experiences. During future appointments, the patient can be quickly reminded of such an exercise in a few seconds.

The psychiatrist is encouraged to explore the available literature and resources to discover useful techniques related to each component of the ACT Hexaflex. Mastery of even just a few of these techniques provdes access to powerful tools that can help patients overcome barriers to achieving behavior changes and improvements in mental health. Additionally, such techniques can be employed to improve commitment to treatment and medication adherence and instill hope for recovery. Developing skills to accept and observe his or her emotions can allow the patient to experience fewer crises and/or require fewer medications. The patient can be directed to online ACT resources, smartphone apps, and ACT bibliotherapy. Once familiar with the basic theoretical underpinnings of ACT and its treatment techniques, the use of such tools can enhance any psychiatric encounter for the patient and bolster the provider’s effectiveness.

References

- Hayes SC, Hofmann SG. The third wave of cognitive behavioral therapy and the rise of process-based care. World Psychiatry. 2017;16(3):245–246.

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2018.

- Segal ZV, Williams JMG, Teasdale JD. Mindfulness-based Cognitive Therapy for Depression. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2013.

- Link JS, Barker T, Serpa S, et al. Mild traumatic brain injury and mindfulness-based stress reduction: a review. Arch Assess Psychol. 2016;6(1): 7–32.

- Twohig MP, Levin ME. Acceptance and commitment therapy as a treatment for anxiety and depression: a review. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2017;40(4):751–770.

- Hayes SC. ACT randomized controlled trials since 1986. Available at: https://contextualscience.org/ACT_Randomized_Controlled_Trials.

- Dindo L, Van Liew JR, Arch JJ. Acceptance and commitment therapy: a transdiagnostic behavioral intervention for mental health and medical conditions. Neurotherapeutics. 2017;14(3):546–553.

- Powers MB, Zum Vorde Sive Vording MB, Emmelkamp PM. Acceptance and commitment therapy: a meta-analytic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(2):73–80.

- Gaudiano BA, Herbert JD.. Acute treatment of inpatients with psychotic symptoms using acceptance and commitment therapy: pilot results. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(3):415–437.

- Forman EM, Herbert JD, Moitra E, et al. A randomized controlled effectiveness trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive therapy for anxiety and depression. Behav Modif. 2007;31(6):772–799.

- Dalrymple KL, Herbert JD. Acceptance and commitment therapy for generalized social anxiety disorder: a pilot study. Behav Modif. 2007;31(5):543–568.

- Woods DW, Wetterneck CT, Flessner CA. A controlled evaluation of acceptance and commitment therapy plus habit reversal for trichotillomania. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(5):639–656.

- Wetherell JL, Afari N, Rutledge T, Sorrell JT, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of acceptance and commitment therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy for chronic pain. Pain. 2011;152(9):2098–2107.

- Juarascio AS, Forman EM, Herbert JD. Acceptance and commitment therapy versus cognitive therapy for the treatment of comorbid eating pathology. Behav Modif. 2010;34(2):175–190.

- Ruiz FJ. A review of acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) empirical evidence: correlational, experimental psychopathology, component and outcome studies. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy. 2010;10(1):125–162.

- Norton AR, Abbott MJ, Norberg MM, Hunt C. A systematic review of mindfulness and acceptance-based treatments for social anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychol. 2015;71(4):283–301.

- Hayes SC, Luoma JB, Bond FW, et al. Acceptance and commitment therapy: model, processes and outcomes. Behav Res Ther. 2006;44(1):1–25.

- Hunot V, Moore TH, Caldwell DM, et al. ‘Third wave’ cognitive and behavioural therapies versus other psychological therapies for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(10):CD008704.

- Harris R. ACT Made Simple: An Easy-to-read Primer on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2009.

- Stoddard JA, Afari N. The Big Book of ACT Metaphors: A Practitioner’s Guide to Experiential Exercises and Metaphors in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2014.

- Harris R. The Happiness Trap. Boulder, CO: Shambhala Publications Inc.; 2008.

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG. Acceptance and Commitment therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2011.

- Williams JMG, Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness: Diverse Perspectives on its Meaning, Origins, and Applications. Abingdon, UK: Routledge; 2013.

- Blackledge JT, Hayes SC. Emotion regulation in acceptance and commitment therapy. J Clin Psychol. 2001;57(2):243–255.

- Luoma JB, Hayes SC, Walser RD. Learning ACT: An Acceptance & Commitment Therapy Skills Training Manual for Therapists. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger Publications; 2007.