by Kari Harper, MD; Nita Bhatt, MD, MPH; and Julie P. Gentile, MD, MBA

Dr. Harper is Assistant Professor, Department of Psychiatry at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. Dr. Bhatt is Associate Professor and Associate Clerkship Director at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. Dr. Gentile is Professor and Chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio.

Funding: No funding was provided for this study.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2023;20(4–6):34–38.

Department Editor

Julie P. Gentile, MD, is Professor and Chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio.

Editor’s Note

The patient cases presented in Psychotherapy Rounds are composite cases written to illustrate certain diagnostic characteristics and to instruct on treatment techniques. The composite cases are not real patients in treatment. Any resemblance to a real patient is purely coincidental.

Abstract

Medical schools around the globe canceled in-person classes and switched to virtual classrooms shortly after the COVID-19 pandemic began. The shift to online platforms posed serious challenges to medical education. During normal conditions, medical school is viewed as a challenging time during which resilience is critically important. There is an intense workload, increasing the risk of burnout and difficulties in work/life balance. In addition to the intensity of the curriculum and clinical rotations, most students accumulate loans that further increase the pressure to succeed. All medical schools are required to offer mental health services for their students. Psychiatrists and other mental health professionals providing care to medical students must consider the unique circumstances during an unprecedented time in the patient’s educational life. This article will review the treatment dynamics created by the medical student-patient and the evidence-based approaches that the psychiatrist can utilize in a psychotherapy setting.

Keywords: Psychiatry, psychotherapy, medical student, medical school, mental illness, mental wellness, pandemic, COVID-19, burnout, resilience

Medical school is an inherently stressful, challenging academic experience that can make students vulnerable to depression, anxiety, and burnout. This time of potential psychological distress has been studied by various researchers.1 The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic added layers of complexity regarding the efficacy of virtual learning methods, personal protective equipment (PPE), protection from the virus for medical students and their families. Life after medical school also often lends itself to a chronically stressful lifestyle.2 Patterns of coping prior to medical school, personality traits, and support systems affect how each individual will manage stress. Also, resilience is an important trait for medical students to cultivate.

Some researchers have investigated the pressures of practicing medicine linked to medical students’ often obsessive, conscientious, and committed personalities.3 The combination of demanding work, a subjective lack of control, and insufficient rewards are powerful sources of stress. The reality is that the imbalance of increasing stress combined with the inability to accommodate the stress will lead to a correction, such as burnout or other stress reactions.

It is a necessity to provide mental health services to all medical students; indeed, it is a requirement of the Licensing Committee on Medical Education (LCME).4 There has been a shift to focus on mental wellness versus mental illness; this lends itself to align with the focus on preventive care in behavioral health, which is as critical as it is in medical health.5

Physicians treating medical students must be aware of the intricacies of physicians treating future physicians.6 The transference and countertransference issues are unique, and we can improve the efficacy of psychotherapy in this patient population by increasing awareness of this unique skill set.

Fictional Case Vignette 1

Student A presented for psychiatric evaluation and treatment toward the end of his first year of medical school. His chief complaint was, “I’m having some trouble with anxiety.”

The student filled out a Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) prior to the appointment and received a score of 8, with most questions being answered that symptoms occurred on “some days.” The suicidal thoughts question was blank, however, and the student had noted that his symptoms made things “extremely difficult.” After some initial rapport-building and gathering of social history, the therapist asked about the reason for the visit.

Dialogue 1

Student A: (starting to cry) I just feel like such a failure. I’ve been working so hard to get to medical school, and now I am in the bottom half of my class. I’ve had to retake a couple of tests this year. I wonder if I am even supposed to be here. I don’t know what I would do if I didn’t become a doctor. I can’t let everyone down!

Therapist: It sounds like this year has not gone as you expected it to, and you are really stressed.

Student A: I’ve never had trouble like this, and it’s going to get worse. We have an exam tomorrow, and I haven’t even studied. I can’t get out of bed, and when I do study, I just keep reading the same page over and over. I feel panicked about the test. I almost canceled this appointment so I could study, but I figured I would just end up lying in bed anyway (cries more).

Therapist: I can see how bad you are feeling. How long have you been feeling sad or down?

Patient A: I don’t know.

Therapist: When do you remember feeling happy?

Patient A: My mom came to visit in September. I remember feeling good then. But at Thanksgiving when I went home, my parents told me they were worried about me. I just thought they didn’t understand.

Therapist: So, it’s been about six months at least? How bad has it gotten? Do you think about quitting medical school?

Patient A: No, I can’t do that.

Therapist: Have you thought about dying?

Patient A: I mean, I wouldn’t kill myself. But sometimes I wonder if it would just be better if I was in a car wreck.

Therapist: I’m sorry you feel so down. Is there anything that helps?

Patient A: I used to like hanging out with my friends. We used to all go out and have a few drinks at the end of the week. I hate going out with them now. I don’t want them to know I had to retake those tests, and I always feel like I should be studying anyway. It does help if I have some wine though. I usually drink a glass or two in the evening. One of my friends told me marijuana helps with their anxiety. I’ve tried it a few times. It helps me go to sleep.

Therapist: You are certainly not the only student who feels like this, and it can get better. It is going to take some work and willingness to change some things, but I will be there to help. Tell me more about the past several months, and then we can develop a plan for you to start feeling better.

Practice Point: Prevalence of Depression, Burnout, and Mental Illness Among Medical Students is Higher than the General Population

According to the Journal of the American Medical Association, “Medical students experience depression, burnout, and mental illness at a higher rate than the general population, with mental health deteriorating over the course of medical training. Medical students have a higher risk of suicidal ideation and suicide, higher rates of burnout, and a lower quality of life than age-matched populations. Medical students are less likely than the general population to receive appropriate treatment despite seemingly better access to care.”7

Research has shown that the most common sources of stress are related to academic and psychosocial concerns, especially high parental expectations, vastness of syllabi, tests/exams, and lack of time. Students typically use active coping strategies, such as positive reframing, planning, acceptance, active coping, self-distraction and emotional support, and alcohol and other substances are used by some students as an unhealthy coping strategy.8 There was evidence of a high prevalence of depression and anxiety among medical students, with levels of overall psychological distress consistently higher than in the general population and age-matched peers by the later years of training. Overall, the studies suggested psychological distress may be higher among female students.9

The most tragic consequence of severe mental health problems in medical students is suicide.10 These studies underscore the importance of making medical students aware of mental health symptoms, their early identification, and the availability of effective and accessible medical student mental health services.

Clinical Pearls

- Medical students are more at risk for mental illness and suicide than age-matched peers.

- Medical students may minimize their symptoms. They are often dedicated, intelligent, and organized, so their grades may not reflect the level of dysfunction they are experiencing.

- Asking about suicide and access to lethal means is a necessary component of treatment.

- Students may develop maladaptive coping strategies, including substance use. Because students are not licensed, there is no governing body to which to report an impaired student. Treating substance use disorders and helping students find appropriate coping strategies may be components of effective treatment.

Fictional Case Vignette 2

During the COVID-19 pandemic, medical students were faced with a number of unique challenges. Some of these challenges continue as we struggle to find a new normal.

Shortly after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, a third-year medical student presented for ongoing treatment after a break during a busy clinical rotation.

Dialogue 2

Therapist: It’s good to see you again. It’s been a while! How have you been?

Student B: (somewhat disheveled) Ugh, I’ve been okay. When did we talk last? March, I think? Well, you know, we went back to clinical rotations. Part of me is glad. I was getting bored and felt useless. Now though, I either still feel useless because I can’t do anything, or I feel scared because we have too many patients with COVID-19 on the unit. At least I don’t feel like school is just on hold anymore. I do like seeing patients, but I have noticed I feel worked up and tense at the end of the day, much more than I did before the pandemic.

Therapist: Tell me more about that feeling of being worked up and tense.

Student B: I just feel like I’m on edge, you know, waiting for something bad to happen. I haven’t had COVID-19 yet. I’m afraid to see my family. My mom has some health problems. What if I give

her COVID-19? I’m not really worried about getting it myself, but I would worry if she did. And I try to stay up to date and listen to the news, but awful things are just happening all the time.

Therapist: This is a really difficult time for many reasons. It sounds like you are feeling pretty isolated. Is that right?

Student B: Yes. I mean, I see other people at the hospital. But that’s not the same. My good friends and I are on different rotations.

Therapist: What are you doing to stay connected to friends and family or otherwise to relieve stress?

Student B: Honestly, I tend to go through a fast-food drive-through and go home and watch TV. I don’t feel like doing anything else. I try to study some, but I usually don’t get much done.

Therapist: Remind me, do you know what specialty you’d like to do?

Student B: (looking brighter) I really want to do obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN)! I had that rotation before COVID-19 started, thankfully. I loved it! I like the surgery and procedure aspect, and labor and delivery was a lot of fun! I have wanted to specialize in OB/GYN since I shadowed a family friend in high school. I ended up working in her office a few summers.

Therapist: Oh wow! Do you ever talk to her now?

Student B: No. She told me to keep in touch, but it’s been a while. She’s really cool. I used to text her questions about medical school. She’s always been supportive.

Therapist: I wonder if you might consider texting her again. I’m sure she would appreciate hearing from you, and it might help you stay connected to why you wanted to go to medical school in the first place. Remembering your end goal can be helpful in the stressful times.

Student B: Yeah, I think I can do that. I’m sure my friends feel isolated too. It’s supposed to be nice this weekend. Do you think it would be okay to go to a park or something with them?

Therapist: Would you feel safe going to a park with them with the risk of COVID-19?

Student B: I just feel like I need to do something. I don’t want to spend another weekend alone, and I’m not seeing my parents anyway. I know my friends are pretty careful too, so I think I would feel safe.

Therapist: It sounds like you have some good ideas that might help you feel a little better!

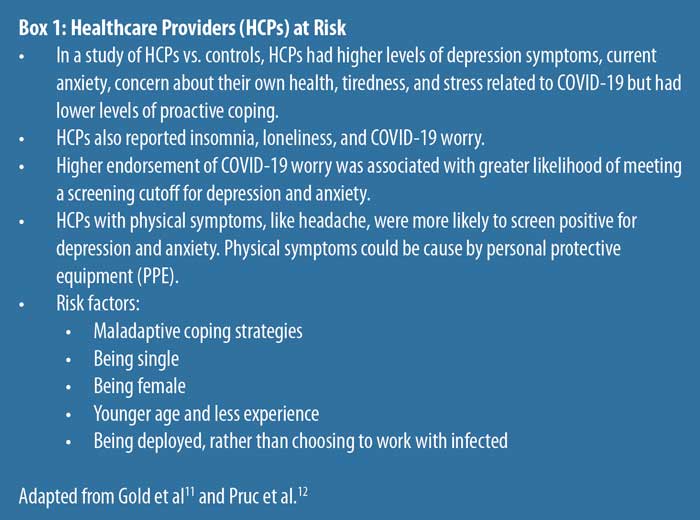

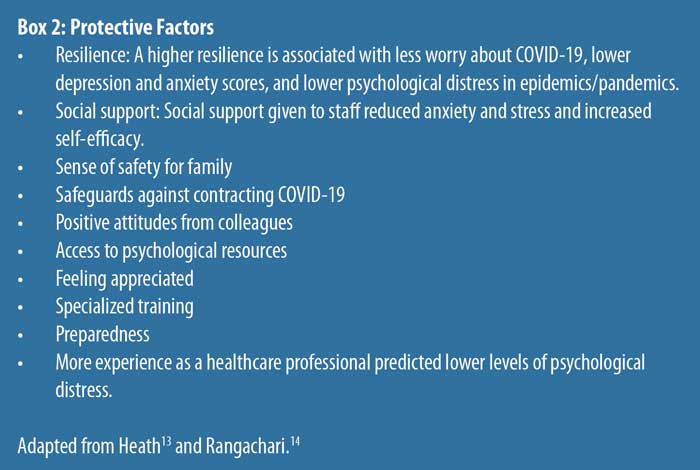

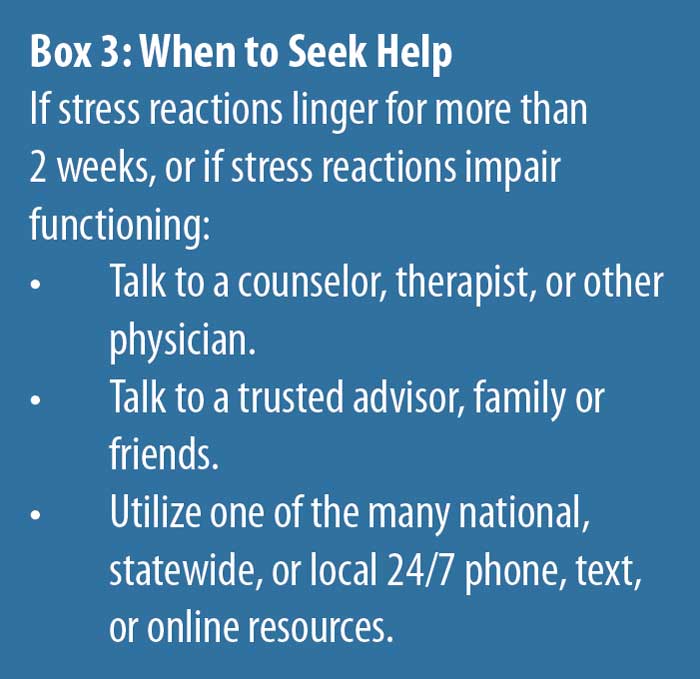

Practice Point: All Healthcare Providers are at Increased Risk of Mental Health Conditions in the Context of the Pandemic

Research regarding the effect of COVID-19 on healthcare workers is ongoing, but thus far clearly indicates higher than normal levels of stress and various emotional/mental symptoms.11,12 Healthcare workers experience these symptoms at a higher level than nonhealthcare workers. The risks for healthcare workers include, but are not limited to, depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), insomnia, burnout/moral injury, substance misuse, and psychological distress.

Clinical Pearls

- Quarantine and isolation have been associated with depression, anxiety, anger, and PTSD.

- Healthcare providers who worked with populations requiring quarantine and isolation due to infection experienced acute stress and PTSD symptoms, exhaustion, detachment, anxiety, depression, irritability, insomnia, poor concentration, deterioration of work performance, alcohol use, and avoidance behavior for up to three years.

- In previous epidemics, healthcare professionals (HCPs) perceived more stress than non-HCPs and experienced higher stress one year later.

- Epidemics and pandemics are associated with psychological distress, insomnia, alcohol and drug misuse, PTSD, depression, and anxiety.

Fictional Case Vignette 3

A second-year medical student called to inquire about opportunities for mental health care.

Dialogue 3

Student C: Hi, I saw the information about medical student mental health services. I’m not sure who to contact or what to do. I think I need to talk to someone.

Therapist: You absolutely contacted the right person. I’m happy to help. Can you tell me more about what you are looking for?

Student C: Well, I’m a little nervous. Who will know I talked to you?

Therapist: That’s understandable and a good question. Mental health services are completely confidential. Is there anyone you are worried about finding out that you are seeking mental health services?

Student C: I just wouldn’t want it to affect my grades, and I don’t want to work with people who know I’ve talked to you.

Therapist: Those concerns are understandable. We keep teaching, supervising, and mental health services completely separate from each other. Your mental health provider will not teach you or evaluate you as a student. Your mental health provider will never contact the school. If your information needs to be shared with anyone, you will have to sign consent for that.

Student C: Okay, that sounds all right. I would like to set up an appointment. I feel like I study all the time. I feel guilty if I ever hang out with my friends. My girlfriend is getting annoyed. I’m so tired. Even though I study every minute I can, I still find myself not retaining the information. I’m afraid I’m going to lose my girlfriend and fail out of medical school! I just feel miserable right now.

Therapist: I’m really glad you called. Let’s get an appointment set up. Many students feel very similarly, and there are definitely some things that can help.

Practice Point: Physicians Treating Physicians in Training

The student’s confidentiality must be carefully protected throughout the entire therapeutic process. Confidentiality should be discussed during the screening, and medical students should be informed of their right to privacy and the mechanisms in place to ensure their privacy. Information in medical records cannot be released without the medical student’s written permission. There should be no communication with parents unless the student requests the communication. Medical students must have the ability to seek mental health services with confidence that the providers of such services will not be in a position at present or in the future to evaluate the student’s academic performance or take part in decisions regarding the student’s advancement or promotion. All directives and recommendations of the LCME must be strictly adhered to throughout the process and delivery of services.4

Medical students may self-refer for mental health services at reliable times in the curriculum. The first year of medical school is well known to hold difficult transitions. Not only does the workload and schedule increase dramatically, but in addition, the content of the curriculum includes the study of abuse, trauma, and other psychological stressors. The second year of medical school is a continuation of academic work that well exceeds students’ time in clinical settings; it also includes extensive preparation for the first in the series of medical licensing board examinations.

The third year of medical school represents a major transition to the clinical years. Interpersonal skills are required to work effectively on teams. Flexibility in work locations, multiple electronic healthcare records systems, and meeting new team members every 2 to 6 weeks are all layers of complication for many students. Rotating through multiple medical specialties can be challenging, and the psychiatry clerkship might be a student’s first experience of hearing countless trauma stories, as well as an in-depth study of depressive and anxiety disorders. Finally, the fourth year begins with major decision-making regarding career path, extensive interviews with residency training programs, and the second medical licensing board examination.

Practice Point: Transference/Countertransference Issues

Transference is defined as the process that leads to attitudes, assumptions, and feelings in the patient that are outgrowths of the patient’s earlier relationships with significant others, especially parents.15 This process is mostly unconscious; it is common for the patient to recreate past emotional relationships and utilize the psychotherapist as the new “object.” Transference can be positive or negative and may be considered a reenactment of a past relationship in the present day.15,16 In the situation of a medical student-patient, the psychiatrist is frequently the object of identification and, if navigated effectively, has the potential to strengthen the therapeutic alliance. Medical students in psychotherapy frequently face the challenge of “fitting” their lives into their educational pursuits. Typically, prior to medical school they “fit” academics into their lives. The fact that the psychiatrist has lived experience in this space sanctions the opportunity to form a unique therapeutic bond.

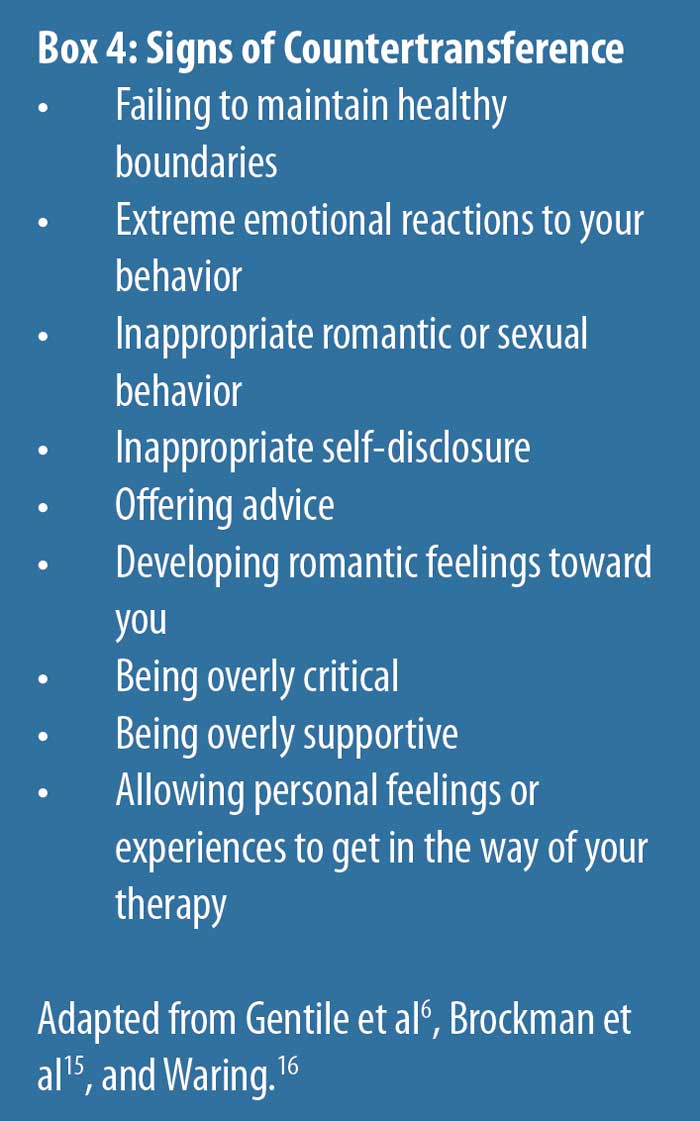

Countertransference is used to describe the psychotherapist’s feelings toward a patient.6,15 This has the potential to provide improved insight into the patient’s experience. A patient who struggles with anxiety can precipitate the psychiatrist to feel anxiety; a patient with borderline personality disorder may cause the psychiatrist to feel manipulated. During the course of therapy, a psychiatrist treating a medical student is very likely to experience the resurfacing of both positive and negative experiences from their time in medical school. The process of recalling these previous events can be helpful if navigated properly. They can increase empathy but should not be projected onto the medical student-patient.

For example, it may be necessary for the psychiatrist to be flexible with scheduling appointments, but this should be kept within reasonable limits and boundaries. If the psychiatrist is overly accommodating, it is important to consider countertransference issues.

With a medical student-patient, the psychiatrist will likely experience a resurfacing of their own emotions and challenges during medical school; this must be navigated carefully, as it will affect the therapeutic alliance. It can lead the psychiatrist to avoid certain topics or create conflicts during sessions.6,15,16 The medical student-patient may exhibit excessive intellectualization, ongoing fear of the breach of confidentiality, idealization of the psychiatrist, or intense identification. The psychiatrist must avoid overidentification that can result in being overly empathic or sympathetic. The other concern is that the psychiatrist may minimize the student’s psychiatric condition.

There is often significant pressure on the psychiatrist treating medical students (future colleagues) to produce results quickly. Alternatively, the psychiatrist may be conflicted with treating a medical student who is sick. It may occur to the psychiatrist that the medical student patient is, after all, making critically important decisions regarding other patients’ health.16 Caution should be utilized to not omit standard and universal monitoring protocols; conversely, extraneous imaging and testing should not be ordered. Avoidance of difficult topics of discussion (e.g., substance misuse, sexual activity, etc.) might be tempting with medical student-patients. Any deviation from the psychiatrist’s typical frame should be cause for reflection and interpretation. There should be a low threshold to seek consultation with colleagues if needed.

Summary

Provision of care for medical students creates unique challenges for the psychiatrist. However, understanding these challenges can help the psychiatrist navigate through the barriers to care created by the status of their future colleagues. Establishing and maintaining a healthy therapeutic alliance, maintaining professional boundaries, and treating the medical student similarly to any other patient are important principles to consider. Reviewing best practice guidelines and seeking consultation can be additionally helpful to the psychiatrist. Furthermore, as with other forms of psychotherapy, recognition and discussion of the emotions created by the transference and countertransference can prove to be therapeutic to the medical student-patient.

References

- Aitkenhead D. Panic, chronic anxiety and burnout: doctors at breaking point. The Guardian. 10 Mar 2018. https://amp.theguardian.com/society/2018/mar/10/panic-chronic-anxiety-burnout-doctors-breaking-point. Accessed 10 Jun 2022.

- O’Byrne L, Gavin B, Adamis D, et al. Levels of stress in medical students due to COVID-19. J Med Ethics. 2021;47(6):383–388.

- Strous R, Shoenfeld N, Lehman A, et al. Medical students’ self-report of mental health conditions. Int J Med Educ. 2012;3:1–5.

- LCME Accreditation for Financial Aid Officers. American Association of Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/services/first-for-financial-aid-officers/lcme-accreditation. Accessed 10 Jun 2022.

- Begum J. What is the difference between mental wellness and mental health? MedicineNet. Reviewed 8 Dec 2021. https://www.medicinenet.com/difference_of_mental_wellness_and_mental_health/article.htm. Accessed 1 Jun 2022.

- Gentile J, Roman B. Medical student mental health services: psychiatrists treating medical students. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2009;6(5):38–45

- Dyrbye L, Massie F, Eacker, A. Relationship between burnout and professional conduct and attitudes among US medical students. JAMA. 2010;304(11):1173–1180.

- Neufeld A, Malin G. How medical students cope with stress: a cross-sectional look at strategies and their sociodemographic antecedents. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):299.

- Rajapuram N, Langness S, Marshall MR, Sammann A. Medical students in distress: the impact of gender, race, debt, and disability. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0243250.

- Rotenstein L, Ramos M, Torre M, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2214–2236.

- Gold J. Covid-19: adverse mental health outcomes for healthcare workers. BMJ. 2020;369:m1815.

- Pruc M, Golik D, Szarpak L, et al. COVID-19 in healthcare workers. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;39:236.

- Heath C, Sommerfield A, von Ungern-Sternberg B. Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(10):1364–1371.

- Rangachari P, Woods J. Preserving organizational resilience, patient safety, and staff retention during COVID-19 requires a holistic consideration of the psychological safety of healthcare workers. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(12):4267.

- Brockman R. Transference, affect, and neurobiology. Psychodyn Psychiatry. 2022;50(1):167–178.

- Waring E. Psychiatric illness in physicians: a review. Compr Psychiatry. 1974;15(6):519–530.