by Waguih William IsHak, MD, FAPA; Paloma Garcia, BS Candidate; Rachel Pearl, MD; Jonathan Dang, MD; Catherine William, BS; Jayant Totlani, BS, DO candidate; and Itai Danovitch, MD, MBA

Drs. IsHak, Pearl, Dang, and Danovitch and Ms. William are with Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California. Dr. IsHak is also with David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles in Los Angeles, California. Ms. Garcia is with Brown University. Mr. Totlani is with Western University of Health Sciences in Pomona, California.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2023;20(4–6):39–48.

Abstract

Objective: This systematic review aims to evaluate the impact of psilocybin on patients experiencing psychiatric symptoms, with a focus on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and safety.

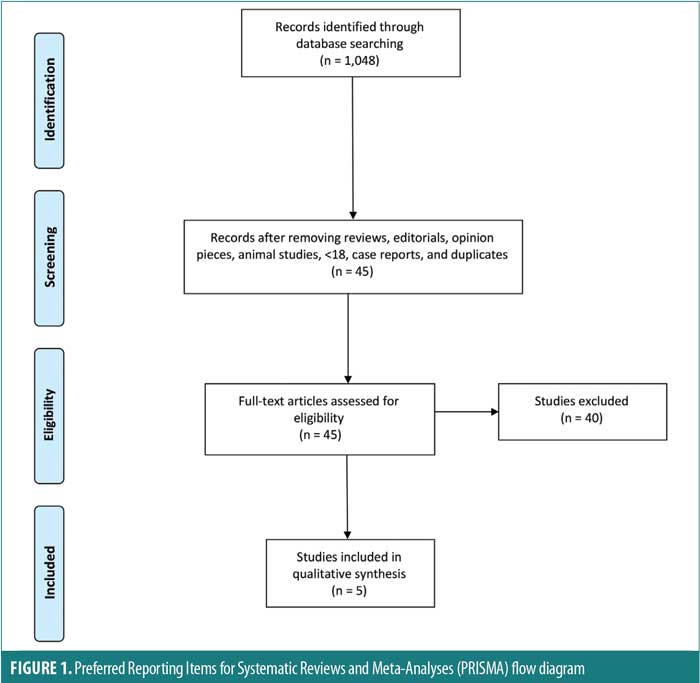

Method of Research: Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, we searched the PubMed database and identified studies published from January 2011 to December 2021 pertaining to the impact of psilocybin on psychiatric symptoms. Two authors independently conducted a focused analysis and reached a final consensus on five studies meeting the specific selection criteria. Study bias was addressed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool.

Results: The impact of psilocybin on psychiatric symptoms was examined in five randomized controlled trials (RCTs). Four studies administered 1 to 2 doses of psilocybin, with doses ranging from 14mg/70kg to 30mg/70kg, and one study administered a fixed dose of 25mg to all participants. Administration of psilocybin resulted in significant and sustained reduction in symptoms of anxiety and depression, enhanced sense of wellbeing, life satisfaction, and positive mood immediately after psilocybin administration and up to six months after conclusion of treatment. All studies included some form of psychotherapy, and none reported serious adverse effects.

Conclusion: RCTs show the efficacy of psilocybin in the treatment of anxiety and depression symptoms, as well as improvement in HRQoL, and no serious side effects. However, additional research is necessary to characterize predictors of treatment response, patient screening requirements, effectiveness in broader clinical populations, and guidelines for psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy.

Keywords: Psilocybin, psychedelics, psychiatric symptoms, anxiety, depression, health-related quality of life

Psilocybin (O-phosphoryl-4-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine) is a 5-hydroxy-tryptamine (5-HT2A) receptor agonist that has shown promising efficacy in treating psychiatric symptoms, particularly in patients with cancer and emotional distress associated with life-limiting illness.1 Psilocybin has not yet been approved by the United States (US) Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for any purpose and is not labeled for the uses discussed in this review, and its use is still investigational. The antidepressant effects of psilocybin are postulated to be mediated by the modulation of 5-HT2A receptors due to its high binding affinity to the 5-HT2A receptor, as well as second messenger signaling and gene-expression effects.2 Furthermore, the effects of psilocybin on perceptual, affective, and cognitive functions, mediated by serotonergic, dopaminergic, and glutamatergic activity, may influence the capacity of an individual’s response to psychotherapy.3,4 The effects of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy have been detected in the long-term, and in some trials, after just one single dose.5,6

Psilocybin, described by the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) as “a hallucinogenic chemical obtained from certain types of fresh and dried mushrooms,” has been classified as a Schedule I drug since 1971.7 In November 2019, psilocybin was granted breakthrough therapy designation by the FDA for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD).8 In November 2020, Oregon became the first state to legalize psilocybin for medical use when voters approved a measure authorizing the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) to create a program permitting licensed physicians to administer psilocybin-producing mushroom and fungi products to individuals 21 years of age or older.9,10 As of December 2021, there were 71 psilocybin studies underway registered on ClinicalTrials.gov, and several states and cities were moving toward the decriminalization of psilocybin for both medical and recreational purposes.11 This systematic review aims to examine the impact of psilocybin on patients experiencing psychiatric symptoms by addressing the following questions: 1) What is the impact of psilocybin on psychiatric symptoms? 2) What is the impact of psilocybin on health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients experiencing psychiatric symptoms? and 3) How safe is psilocybin for patients experiencing psychiatric symptoms?

Methods

Search strategy. This systematic review was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA).12 A systematic literature search was conducted in PubMed, using the keyword “psilocybin,” for articles pertaining to psychiatric symptoms published between January 2011 to December 2021, after setting exclusion and inclusion criteria. A manual search of reference lists for identified papers and previous reviews was also conducted.

Study selection criteria and methodology. The following inclusion criteria were used: articles published in English or with a published English translation; articles published in a peer reviewed journal (which all PubMed articles are); original studies in human adults (no reviews, no animal studies, no study subjects under 18 years of age); randomized controlled trials (RCTs); studies that used at least one assessment measure; and studies performed on patients experiencing psychiatric symptoms, as opposed to healthy subjects. Exclusion criteria included reviews, editorials, opinion pieces, and case reports. Two authors independently conducted a focused analysis and reached consensus on five studies meeting the specific selection criteria. An additional independent author examined the quality of each study by identifying its risk of bias using the Cochrane risk of bias tool, as well A Measurement Tool to Assess Systematic Reviews 2 (AMSTAR 2) checklist, as detailed in the section below. The search method is displayed in a PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1.13–15

Data extraction and yield. Key findings were derived from the full text and figures of the selected five studies. The study designs and findings were analyzed for quality and are detailed in Table 1.

Risk of bias and study quality. The quality of each study was assessed using the Cochrane risk of bias tool, which includes six criteria against which potential risk of bias is judged: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selectivity of outcome reporting, and other biases.13,14 A summary of the risk of bias is presented in Table 2.

Quality of the current systematic review. For the quality of the present systematic review, the AMSTAR 2 checklist was utilized to ensure all components of a high-quality systematic review were addressed.14,15 AMSTAR 2 consists of 16 items in total and is presented in Table 3.

Results

Overview. The impact of psilocybin on psychiatric symptoms was examined in five randomized clinical trials: Grob et al (2011),1 Ross et al (2016),16 Griffiths et al. (2016),5 Davis et al. (2021),17 and Carhart-Harris et al. (2021).18 The findings from the reviewed studies are summarized in Table 1.

All five RCTs were double-blind studies, except for one open-label study, and they included three crossover and two parallel-design studies. Three studies administered psilocybin to patients with cancer and an anxiety-related Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition (DSM-IV) diagnosis, whereas two studies focused on MDD. The sample sizes in the studies ranged from 12 to 59 patients. Four of the studies administered 1 to 2 doses of psilocybin, with doses ranging from 14mg/70kg to 30mg/70kg, whereas one study18 administered a fixed dose of 25mg to all participants. All five studies included some form of psychotherapy/counseling within their treatment protocol. Three studies included participant meetings with study clinicians both before and after psilocybin sessions for the purposes of trust-building, information gathering, and therapy, and two studies provided supportive psychotherapy. The duration of treatment spanned from one day to 11 weeks. Follow-up measures were collected as soon as one day and up to 26 weeks after treatment. Additional long-term follow-ups after 3.2 and 4.5 years were conducted and published separately for one study. The measurement instruments employed by the reviewed studies for the assessment of psilocybin effects are detailed in Table 4.

What is the impact of psilocybin on patients experiencing psychiatric symptoms? The five RCTs demonstrated the efficacy of psilocybin in reducing anxiety and depressive symptoms.

Grob et al’s (2011)1 double-blind, crossover RCT (n=12) evaluated the impact of a single medium dose of psilocybin (14mg/70kg) on patients with advanced-stage cancer and an anxiety-related DSM-IV diagnosis using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI), and Profile of Mood States (POMS) as primary outcome measures. The study demonstrated a significant reduction in depressive symptoms at six months after administration, as measured by the BDI (p<0.05). According to STAI measures, trait anxiety was also significantly reduced from baseline when reassessed at one (p<0.05) and three months (p=0.03) after treatment. No significant effect was found for state anxiety, and no serious adverse events (AEs) were reported.1

Ross et al’s (2016)16 double-blind, crossover RCT (n=29) reported similar findings after a single high dose of psilocybin (21mg/70kg) was given to patients with cancer and an anxiety-related DSM-IV diagnosis, using the BDI, STAI, and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) as primary outcomes. Seven weeks after psilocybin administration, scores were significantly reduced on measures of state anxiety (d=1.18; p<0.01), trait anxiety (d=1.29, p<0.001), and depression (p<0.05 for BDI and p<0.01 for HADS Depression, d=0.82 and 0.98, respectively), compared to the control group. These effects remained significant after 26 weeks for HADS total score (p<0.05) and reduction of state anxiety (p<0.05). Feelings of hopelessness and demoralization were significantly reduced in the study group, compared to controls, two weeks after a dose of psilocybin (both p<0.01). Furthermore, significant positive behavioral changes were seen in the psilocybin group two weeks after administration, compared to the placebo group (p≤0.001). Feelings of death transcendence (defined as acceptance of and positive feelings toward the end of life) were significantly increased 26 weeks after psilocybin administration (p<0.05). Interestingly, after psilocybin administration, scores on mystical experience, as measured by the Mystical Experience Questionnaire (MEQ30), correlated significantly with reductions in BDI depression scores (r=0.49, p=0.01), state anxiety scores (r=0.42, p=0.03), and trait anxiety scores (r=0.39, p=0.04). AEs included increased blood pressure and heart rate, headache, nausea, transient anxiety, and “transient psychotic-like symptoms,” none which were deemed serious.16 Importantly, 15 out of the 16 participants who remained alive agreed to participate in a long-term follow-up study that was published separately.6 The results showed statistically significant improvements in anxiety and depression primary measures from baseline after 3.2 years (mean d=1.30, range: 0.93–1.97) and 4.5 years (mean d=1.41, range: 0.86–1.89). Moreover, 60 to 80 percent of patients at the second (4.5 year) follow-up met criteria for clinically significant antidepressant or anxiolytic responses.6

Griffiths et al’s (2016)5 double-blind, crossover RCT (n=51) administered one high dose (20–30mg/70kg) of psilocybin and one very low dose (1–3mg/70kg) as placebo to patients with potentially terminal illness due to cancer and a DSM-IV diagnosis that included anxiety or mood symptoms, using the GRID-Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (GRID-HAMD) and Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) as primary outcome measures. At the six-month follow-up, scores improved significantly from baseline on the GRID-HAMD (d=2.98) and HAM-A (d=3.40), in addition to BDI (d=1.63), HADS Depression (d=1.65), HADS Anxiety (d=2.15), state anxiety (d=1.25), and trait anxiety (d=1.20; all p<0.001). Importantly, high scores on mystical experience, as measured by the MEQ30, correlated significantly with reduced scores on six measures of depression and anxiety, including HADS Depression (r=-0.36, p<0.01) and HAM-A (r=-0.59, p<0.0001) five weeks later. At five weeks and six months, recipients of high-dose psilocybin reported significantly increased positive attitude, mood, social effects, and behavior, compared to subjects receiving the very low placebo dose of psilocybin (all p<0.001). At six months, there were significant increases in death transcendence and community observer ratings of positive mood and behavioral ratings (both p<0.001), compared to baseline. AEs included increased blood pressure, nausea, and vomiting, which were not deemed serious.5

Davis et al’s (2021)17 open-label, parallel-design RCT (n=24) examined the impact of psilocybin-assisted therapy on patients with MDD, compared to a waitlist control group, using the GRID-HAMD as the primary outcome measure. During the eight-week intervention period, the study administered two high doses of psilocybin, 20mg/70kg in the first session and 30mg/70kg in the second session, spaced 1 to 2 weeks apart. Patients in the psilocybin therapy group experienced significantly reduced GRID-HAMD scores after one (d=2.2) and four weeks (d=2.6), compared to the control group (all p<0.001). Four weeks after treatment, 71 percent of patients had a 50-percent or greater reduction in GRID-HAMD scores, and 54 percent met criteria for remission of depression. Psilocybin-assisted therapy significantly reduced the mean score on the Quick Inventory of Depression Symptomology-Self-Rated (QIDS-SR) from baseline to Day 1 after the first psilocybin session (d=3.0) and remained significantly reduced through Week 4 after the second session (d=3.1; all p<0.001). AEs included headache, but otherwise no serious adverse effects were noted.17

Carhart-Harris et al’s (2021)18 double-blind, parallel-design RCT (n=59) examined the noninferiority of psilocybin, compared to the standard antidepressant escitalopram, in patients with long-standing (15–22 years) moderate-to-severe MDD. Patients were randomized to receive either two high doses of psilocybin (25mg) three weeks apart or daily escitalopram plus two very low doses (placebo) of psilocybin three weeks apart. After six weeks, the primary outcome measure of improved depression scores on the QIDS-SR from baseline were not significantly different between the two groups (p=0.17). This trial established the noninferiority of psilocybin at six weeks to conventional, daily selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) treatment for long-standing major depression. Remarkably, 70 percent of patients in the high-dose psilocybin group versus 48 percent of patients in the very low psilocybin plus escitalopram group achieved response (reduction in QIDS-SR of >50%), and 57 percent versus 28 percent, respectively, achieved remission. No serious AEs were observed.18

What is the impact of psilocybin on HRQoL in patients experiencing psychiatric symptoms? The two RTCs that included HRQoL measures showed significant improvement in HRQoL in patients experiencing psychiatric symptoms.

Ross et al (2016)16 studied 29 patients with cancer and an anxiety-related DSM-IV diagnosis and found a significant increase in ratings of wellbeing/life satisfaction two weeks after one high-dose psilocybin session (p≤0.001). There were similar findings regarding ratings of physical health (p≤0.01). These differences remained significant when comparing ratings up to 33 weeks after psilocybin administration with ratings two weeks after placebo administration (both p≤0.01).16

Griffiths et al (2016)5 studied 51 patients with terminal cancer and a DSM-IV diagnosis of a mood or anxiety disorder and showed that one high dose of psilocybin, compared to one very low dose (placebo), led to a significant increase in ratings on overall quality of life (d=1.14), meaningful existence (d=1.12), and optimism (d=0.66; all p<0.001) at five weeks, which remained higher in the study group at six months, compared to baseline. The study also reported higher ratings of wellbeing/life satisfaction among those who received a high dose of psilocybin, compared to placebo, at five weeks and six months (both p<0.001).5

How safe is psilocybin in patients experiencing psychiatric symptoms? Regarding safety, none of the five studies reported occurrence of serious AEs. Two of the RCTs evaluating psilocybin in patients with cancer, Ross et al (2016)16 and Griffiths et al (2016),5 noted minor AEs, including nonclinically significant increases in heart rate and blood pressure, as well as gastrointestinal complaints, such as nausea and vomiting. Headache was reported in the studies by Ross et al (2016)16 and Davis et al (2021).17

Discussion

Findings from RCTs indicate that psilocybin, when used in conjunction with therapy, may alleviate symptoms of depression and anxiety as early as 2 to 4 weeks from administration, with long-term sustainment of positive mood. RCTs showed improvement in HRQoL, and none of the reported side effects were deemed to be serious. While most studies were small, the most rigorous study to date suggests that psilocybin has comparable efficacy to escitalopram in reducing depression at six weeks from administration.18 In patients with terminal cancer, HRQoL improved after psilocybin therapy, with long-term results in the order of several years.6 The findings from this systematic review indicate that psilocybin is generally well tolerated and produces a host of immediate and sustained beneficial effects for patients with cancer suffering from symptoms of depression and anxiety. Additionally, the striking response (70% vs. 48%) and remission (57% vs. 28%) secondary outcome measures of high-dose psilocybin versus escitalopram in the Carhart-Harris et al (2021)18 study merit replication and subgroup analyses in order to identify who would benefit most from psilocybin treatment.

Our findings, while focused on RCTs (the gold standard for effectiveness research) are consistent with evidence from systematic reviews that have reviewed a variety of study designs of psilocybin use in depression and anxiety.19–23 However, the lack of information on how to predict who would be at risk for AEs continues to be a concern in clinical and research applications. Additional limitations include a small quantity of RCTs, relatively small sample sizes, demographic homogeneity, challenges related to adequate blinding, heterogeneous target outcome measures, and the context-dependent nature of the efficacy of psilocybin.24 Current research indicates that psilocybin is particularly valuable within a psychotherapeutic context, where individuals can develop new perspectives brought about by the actual cognitive and emotional changes precipitated by psilocybin, as seen in Davis et al (2021)17

While preliminary studies are promising, a standardized protocol for psilocybin administration for patients with cancer would require expanded research on safety and efficacy as a means for establishing formal treatment guidelines to suit individual patient needs. Findings from patients in existing studies might not generalize well to clinical populations, especially when considering compromised cardiovascular, renal, and/or hepatic function associated with cancer progression and use of chemotherapy, where pharmacokinetics may be less predictable. Many cancer survivors report a fear of recurrence or describe living in a constant state of “waiting for the other shoe to drop.” Qualitative reports suggest that patients receiving psilocybin-assisted therapy have been able to unburden themselves of such feelings.19 However, additional rigorous clinical trials are needed to establish a cost-benefit analysis for this subset of patients in the context of a psilocybin safety profile. There is also a need to investigate ways of avoiding or minimizing AEs associated with psilocybin, such as headache, nausea, vomiting, and blood pressure elevation, particularly in patients with active medical issues, such as cancer. A promising study showed that a 14-day administration of escitalopram prior to administration of psilocybin reduced these side effects.25

A systematic review of psilocybin dosing by Li et al26 concluded that the most effective treatment for depression is achieved at doses of 30mg/70kg. The administration of 20mg/70kg or above of psilocybin may require additional monitoring and psychological support before, during, and after treatment.27 A 2021 press release2 about an RCT by COMPASS (n=233) that is yet to be published in a peer-reviewed journal showed that twice the number of patients with treatment-resistant depression (TRD) in the 25mg group achieved response and remission at Weeks 3 and 12, compared to the 1mg group. Twelve patients overall (0.43%) reported suicidal behavior, intentional self-injury, and suicidal ideation.2 While these phenomena occur in TRD, they were reported more frequently in the 25mg group than in the 1mg group. It is difficult to interpret this information without a published peer-reviewed report that includes methodology and more specifics, especially because no suicidal ideation or behaviors were detected in the five studies we reviewed. Furthermore, findings from Ross et al (2021)29 and Hendricks et al (2015)30 suggest that psilocybin may decrease suicidal ideation. Nonetheless, such concerns must be taken into consideration when constructing frameworks for widespread psilocybin treatment and should be explored in further studies evaluating psilocybin regarding dose, duration, concurrent therapy, and predictors of self-harm ideations and behaviors.

It should also be noted that current research efforts are investigating the impact of psychedelic-assisted therapy on a broader scope of psychiatric disorders. Santos et al31 reviewed studies showing the efficacy of psilocybin in the management of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and depression, as well as tobacco and alcohol use. Gard et al32 reviewed case studies showing a positive, albeit weak, response of bipolar depression to psilocybin. According to a preliminary study by Woolley et al33 (n=18) at ClinicalTrials.gov, participants with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and psychiatric symptoms showed improvement at the conclusion of a seven-week treatment with psilocybin and group therapy, as well as at three months posttreatment.

Despite legalization attempts, psilocybin remains at Schedule I status at the US federal level. A 2018 review by investigators at Johns Hopkins University, using the eight factors used by the Controlled Substances Act to schedule controlled substances, concluded that it would be appropriate to schedule psilocybin for Schedule IV (which also includes benzodiazepines and hypnotics).34,35 Therefore, the issue of potential abuse must be the subject of prospective clinical studies in order to put this issue to rest.36

Limitations and strengths. The primary limitation of this review lies in the context-dependent nature of psilocybin’s efficacy. The set (an individual’s expectations and current psychological state) and setting (the environment in which the experience occurs) are thought to be key predictors in psychedelic experience outcomes.23 Thus, findings from these studies may be influenced by an additional independent variable: the quality of the set and setting. While many of the reviewed studies recognized the importance of these factors in promoting positive outcomes and incorporated them into their study design, studies varied significantly in their methods, with no established standard protocol.

The variability of psilocybin dosages from 14mg to 30mg per 70kg and broad range of follow-up times can be viewed as a strength because they provide an opportunity for comparison between different psilocybin treatment methods. Furthermore, this lays the framework for future work to delineate the relationship between these factors and efficacy of treatment. It is also necessary to evaluate the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of psilocybin on patients who are at risk for psychotic disorders. Other study-specific limitations include the fact that many patients in the studies by Grob et al1 (66% of participants) and Griffiths et al5 (45% of participants) had prior experience with hallucinogenic substances, and the study by Grob et al had a relatively small sample size of 12, which included 11 (87.5%) female subjects. The study by Griffiths et al5 lacked educational diversity, with 98 percent of subjects having a bachelor’s degree at minimum. The study by Davis et al17 lacked a standard psychotherapy approach and involved a group of counselors with various educational backgrounds on psychotherapy. Finally, it should be noted that the psychedelic nature of psilocybin makes a placebo-controlled study unlikely to be truly blinded.

Conclusion

This systematic review of RCTs shows the efficacy of psilocybin in the treatment of anxiety and depression symptoms, as well as improvement in HRQoL, and no serious AEs. Future research should address predictors of treatment response, patient screening requirements, effectiveness in broader clinical populations, and guidelines for psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy.

References

- Grob CS, Danforth AL, Chopra GS, et al. Pilot study of psilocybin treatment for anxiety in patients with advanced-stage cancer. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(1):71–78.

- Mahapatra A, Gupta R. Role of psilocybin in the treatment of depression. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2017;7(1):54–56.

- Heuschkel K, Kuypers KPC. Depression, mindfulness, and psilocybin: possible complementary effects of mindfulness meditation and psilocybin in the treatment of depression. A review. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:224.

- De Gregorio D, Enns JP, Nuñez NA, et al. d-Lysergic acid diethylamide, psilocybin, and other classic hallucinogens: mechanism of action and potential therapeutic applications in mood disorders. Prog Brain Res. 2018;242:69–96.

- Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1181–1197.

- Agin-Liebes GI, Malone T, Yalch MM, et al. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for psychiatric and existential distress in patients with life-threatening cancer. J Psychopharmacol. 2020;34(2):155–166.

- United States Drug Enforcement Agency. Psilocybin. https://www.dea.gov/factsheets/psilocybin. Accessed 29 Jan 2021.

- COMPASS Pathways. COMPASS Pathways receives FDA breakthrough therapy designation for psilocybin therapy for treatment resistant depression. 23 Oct 2018. https://compasspathways.com/compass-pathways-receives-fda-breakthrough-therapy-designation-for-psilocybin-therapy-for-treatment-resistant-depression/. Accessed 20 Jul 2021.

- State of Oregon. Measure to legalize psilocybin therapy. 2020. http://oregonvotes.org/irr/2020/034text.pdf. Accessed 29 Jan 2021.

- State of Oregon. Measure 109 explanatory statement. http://oregonvotes.gov/voters-guide/english/Measure109Explanatory.html. Accessed 29 Jan 2021.

- ClinicalTrials.gov: 60 studies found for: psilocybin. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results?cond=&term =psilocybin&cntry=&state=&city=&dist=. Accessed 22 Jun 2021.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

- Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:ED000142.

- Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, et al (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 6.1. Cochrane; 2020. Updated Sep 2020.

- Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, et al. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008.

- Ross S, Bossis A, Guss J, et al. Rapid and sustained symptom reduction following psilocybin treatment for anxiety and depression in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30(12):1165–1180.

- Davis AK, Barrett FS, May DG, et al. Effects of psilocybin-assisted therapy on major depressive disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78(5):481–489.

- Carhart-Harris R, Giribaldi B, Watts R, et al. Trial of psilocybin versus escitalopram for depression. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(15):1402–1411.

- Aday JS, Mitzkovitz CM, Bloesch EK, et al. Long-term effects of psychedelic drugs: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2020;113:179–189.

- Goldberg SB, Pace BT, Nicholas CR, et al. The experimental effects of psilocybin on symptoms of anxiety and depression: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;284:112749.

- Vargas AS, Luís Â, Barroso M, et al. Psilocybin as a new approach to treat depression and anxiety in the context of life-threatening diseases-a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Biomedicines. 2020;8(9):331.

- Muttoni S, Ardissino M, John C. Classical psychedelics for the treatment of depression and anxiety: a systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2019;258:11–24.

- Reiff CM, Richman EE, Nemeroff CB, et al. Psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(5):391–410.

- Carhart-Harris RL, Roseman L, Haijen E, et al. Psychedelics and the essential importance of context. J Psychopharmacol. 2018;32(7):725–731.

- Becker AM, Holze F, Grandinetti T, et al. Acute effects of psilocybin after escitalopram or placebo pretreatment in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over study in healthy subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2022;111(4):886–895.

- Nan-Xi Li, Hu YR, Chen WN, Zhang B. Dose effect of psilocybin on primary and secondary depression: a preliminary systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2022;296:26–34.

- Johnson M, Richards W, Griffiths R. Human hallucinogen research: guidelines for safety. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;22(6):603–620.

- COMPASS Pathways. COMPASS Pathways announces positive topline results from groundbreaking Phase IIb trial of investigational COMP360 psilocybin therapy for treatment-resistant depression. 9 Nov 2021. https://ir.compasspathways.com/news-releases/news-release-details/compass-pathways-announces-positive-topline-results. Accessed 7 Apr 2023.

- Ross S, Agin-Liebes G, Lo S, et al. Acute and sustained reductions in loss of meaning and suicidal ideation following psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for psychiatric and existential distress in life-threatening cancer. ACS Pharmacol Transl Sci. 2021;4(2):553–562.

- Hendricks PS, Johnson MW, Griffiths RR. Psilocybin, psychological distress, and suicidality. J Psychopharmacol. 2015;29(9):1041–1043.

- Castro Santos H, Gama Marques J. What is the clinical evidence on psilocybin for the treatment of psychiatric disorders? A systematic review. Porto Biomed J. 2021;6(1):e128.

- Gard DE, Pleet MM, Bradley ER, et al. Evaluating the risk of psilocybin for the treatment of bipolar depression: a review of the research literature and published case studies. J Affect Disord Rep. 2021;6:100240.

- Woolley J. Psilocybin-assisted group therapy for demoralization in long-term AIDS survivors. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02950467. Updated 7 Jan 2021. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02950467. Accessed 7 Apr 2023.

- Johnson MW, Griffiths RR, Hendricks PS, Henningfield JE. The abuse potential of medical psilocybin according to the 8 factors of the Controlled Substances Act. Neuropharmacology. 2018;142:143–166.

- United States Drug Enforcement Agency. The Controlled Substances Act. https://www.dea.gov/drug-information/csa. Accessed 22 Feb 2022.

- Smith WR, Appelbaum PS. Two models of legalization of psychedelic substances: reasons for concern. JAMA. 2021;326(8):697–698.