by Isha Snehal, MD; Garret Lorenzen, MS; and Ashish Sharma, MD

Dr. Snehal is with Department of Neurological Sciences, University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, Nebraska. Mr. Lorenzen is with College of Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, Nebraska. Dr. Sharma is with Department of Psychiatry, University of Nebraska in Omaha, Nebraska.

Funding: No funding was provided for this article.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2023;20(4–6):49–52.

Abstract

Bupropion has been in use for several decades. It is widely used for major depressive disorder (MDD), seasonal affective disorder (SAD), and smoking cessation. It is also a treatment of choice for mild-to-moderate depression and is prescribed for atypical and melancholic depression. However, bupropion overdose can lead to serious neurological and cardiovascular adverse effects. We report a recent case of bupropion overdose and review published cases in the literature to present the spectrum of clinical findings and treatments used to overcome the effects of bupropion overdose. Per our findings, bupropion doses of 2.7g and upward can lead to seizures and cause encephalopathy and cardiovascular effects. Higher doses could also lead to intubation and increased hospital stay. Therefore, patients with an increased risk of cardiovascular issues and seizures should be evaluated before starting the medication or increasing the dosage.

Keywords: Bupropion, overdose, seizures, depression

Bupropion (Wellbutrin) has been used in the United States (US) since 1989.1 Its mechanism of action involves norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin reuptake inhibition with mild anticholinergic activity, which has been incompletely understood.2

Bupropion is used to treat major depressive disorder (MDD), seasonal affective disorder (SAD), and smoking cessation. In addition, bupropion has been used off-label to treat bipolar depression and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).3 To avoid adverse events (AEs), including an increased risk of seizures, patients may use up to a maximum dose of bupropion 450mg per day, with a maximum single dose not exceeding 150mg of the immediate-release formulation in a single dose.4

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved bupropion for depression, and the extended-release form has been approved for smoking cessation. Berigan et al3 mention that bupropion has a benign side effect profile, and it is recommended for use in elderly patients with depression and in anxiety associated with depression. It is also useful when used with lithium as an adjunct in patients with rapid cycling bipolar disorder.5

Given the increased levels of norepinephrine and dopamine, more than 10 percent of patients taking bupropion report dry mouth, insomnia, headache, and nausea. Other rarely reported side effects include restlessness, anxiety, constipation, dizziness, nasopharyngitis, and fatigue or blurred vision/acute angle glaucoma.6,7 In rarer cases, cardiac arrythmias and neurologic disturbances can be found, depending on the dosage.8 Bupropion is also known to be contraindicated in patients with suicidal tendencies, and thus should be used with caution in such patients.9

In this case report, we present a case documenting the events after a bupropion overdose and discuss the presentation, events, and management of bupropion overdose from the published literature. These case reports were collected from PubMed with the search terms “bupropion” or “Wellbutrin” and “overdose.”

Case Presentation

The patient was a 50-year-old female with a prior history of self-harm who was brought to the emergency department (ED) after a suicide attempt. She had a bupropion prescription for depression. She had taken over 90 tablets of bupropion 300mg and drunk eight cans of beers six hours prior to presentation. She had been depressed in the days prior to presentation.

In the ED, she was given activated charcoal, which was later discontinued due to poor tolerance. While she was initially awake and alert, she soon had a tonic-clonic seizure, associated with urine incontinence, foaming at the mouth, and unresponsiveness within four hours of admission. She had elevated liver function tests (LFTs) due to congestive hepatopathy and developed hypotension with acute kidney injury. She was then sedated with midazolam and propofol, and a routine electroencephalogram (EEG) was done to rule out seizures. Findings showed diffuse polymorphic slowing suggestive of encephalopathy. Lorazepam 6mg and levetiracetam 1g was administered, and she was intubated for airway protection. She had perioral, facial, and eyebrow twitching, which was attributed to metabolic myoclonus by neurology staff. She continued to deteriorate, with profound hypotension and bradycardia requiring large doses of epinephrine, norepinephrine, dopamine, and phenylephrine.

She developed wide complex cardiac rhythm before developing bradycardia and becoming pulseless. She received cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), multiple rounds of epinephrine, two doses of intravenous (IV) amiodarone, multiple boluses of bicarbonate, calcium supplementation, and magnesium. Return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) was achieved, but she continued to have bradycardia. She then developed metabolic and respiratory acidosis, which was resolved with bicarbonate infusions. Bradycardia was resolved with acidosis correction. She was transferred to a different hospital for higher level of care, as she needed extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO). She was eventually weaned off pressor support and extubated prior to transfer to the floor. Psychiatry staff was consulted on the patient’s suicide attempt, and they recommend inpatient treatment.

Discussion

Our patient had a new onset seizure, then experienced cardiovascular problems, causing her to be transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU) for management.

As documented in Table 1, bupropion can cause catastrophic effects on overdose, which can be fatal if not managed appropriately. Most notable are the cardiac arrythmias, such as QTC prolongation, and dose-related seizures.10 These seizures are hypothesized to be due to increased concentration of sympathomimetics and activation of hypothalamic pathways. Risk factors include abrupt discontinuation of ethanol, benzodiazepines, or antiepileptic drugs; excessive use of drugs that lower seizure threshold, such as opioid analgesics, antimalarials, fluroquinolones, and some antipsychotics; and presence of electrolyte or metabolic disturbances.2,22 History of bulimia or anorexia nervosa also increases risk of seizure activity.11,12

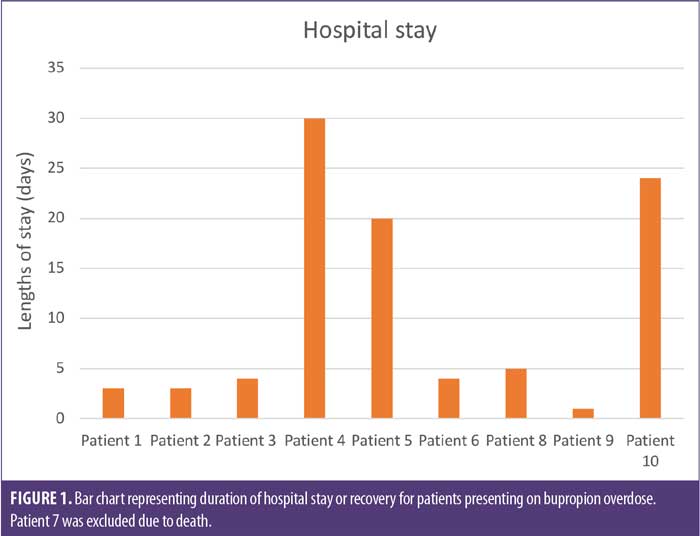

Table 1 reviews case reports of bupropion overdose. Doses of bupropion 2.7g or higher can lead to seizures and might cause encephalopathy and cardiovascular effects. Higher doses could also lead to intubation and increased hospital stay.13,14 In the series of documented case reports, it was found that the hospital stay varied from 24 hours to almost a month (Figure 1). This could be variable depending on the comorbidities and complications. Some patients developed ventilator-associated pneumonia, and others needed longer periods of cardiovascular support.

Conclusion

This case report and review demonstrates that bupropion overdose may be fatal and can have very serious consequences in a patient. Acute and ICU level of care is essential in these cases. A range of cardiovascular and neurological presentations are possible, and treatment may involve antiseizure medications, pressor support, and detoxification using different techniques.

Therefore, patients with increased risk of cardiovascular issues and seizures should be evaluated before starting the medication or increasing the dosage. They should also be warned against overdose, especially in difficult mental health circumstances.

References

- Fava M, Rush AJ, Thase ME, et al. 15 years of clinical experience with bupropion HCl: from bupropion to bupropion SR to bupropion XL. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(3):106–113.

- Kim EJ, Felsovalyi K, Young M, et al. Molecular basis of atypicality of bupropion inferred from its receptor engagement in nervous system tissues. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2018;235(9): 2643–2650.

- Berigan TR. The many uses of bupropion and bupropion sustained release (SR) in adults. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;4(1):30–32.

- Davidson J. Seizures and bupropion: a review. J Clin Psychiatry. 1989;50(7):256–261.

- Haykal RF, Akiskal HS. Bupropion as a promising approach to rapid cycling bipolar II patients. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51(11):450–455.

- Symes RJ, Etminan M, Mikelberg FS. Risk of angle-closure glaucoma with bupropion and topiramate. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2015;133(10):1187–1189.

- Patel K, Allen S, Haque MN, et al. Bupropion: a systematic review and meta-analysis of effectiveness as an antidepressant. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2016;6(2):99–144.

- Spiller HA, Ramoska, EA, Krenzelok EP, et al. Bupropion overdose: a 3-year multi-center retrospective analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12(1):43–45.

- Huecker MR, Smiley A, Saadabadi A. Bupropion. Updated 15 Dec 2022. In: StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing.

- Costa R, Oliveira NG, Dinis-Oliveira RJ. Pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic of bupropion: integrative overview of relevant clinical and forensic aspects. Drug Metab Rev. 2019;51(3):293–313.

- Israël M. Should some drugs be avoided when treating bulimia nervosa? J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2002;27(6):457.

- Marvanova M, Gramith K. Role of antidepressants in the treatment of adults with anorexia nervosa. Ment Health Clin. 2018;8(3):127–137.

- Kara H, Ak A, Bayır A, et al. Seizures after overdoses of bupropion intake. Balkan Med J. 2013;30(2):248–249.

- Stranges D, Lucerna A, Espinosa J, et al. A Lazarus effect: a case report of bupropion overdose mimicking brain death. World J Emerg Med. 2018;9(1):67–69.

- Jessica PN, Susanti IR, Paul S, et al. Back from the dead: a case of bupropion overdose mimicking brain death. J Clin Toxicol. 2020;10(4):1-3.

- Morazin F, Lumbroso A, Harry P, et al.Cardiogenic shock and status epilepticus after massive bupropion overdose. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017;45(7):794–797.

- Storrow AB. Bupropion overdose and seizure. Am J Emerg Med. 1994;12(2):183–184.

- Sathe AR, Thiemann A, Toulouie S, et al. A 19-year-old woman with a history of depression and fatal cardiorespiratory failure following an overdose of prescribed bupropion. Am J Case Rep. 2021;22:e931783.

- Bornstein K, Montrief T, Anwar Parris M. Successful management of adolescent bupropion overdose with intravenous lipid emulsion therapy. J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2019;8(4):242–246.

- Ayers S, Tobias JD. Bupropion overdose in an adolescent. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2001;17(2):104–106.

- Heise CW, Skolnik AB, Raschke RA, et al. Two cases of refractory cardiogenic shock secondary to bupropion successfully treated with veno-arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation. J Med Toxicol. 2016;12(3):301–304.

- Hitchings, Andrew W. Drugs that lower the seizure threshold. Adverse Drug React Bull. 2016;298(1):1151–1154.