by Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD

Ms. Vanderpool is Director of Risk Management at Professional Risk Management Services (PRMS).

Funding: No funding was provided for the preparation of this article.

Disclosures: The author is an employee of PRMS. PRMS manages a professional liability insurance program for psychiatrists.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2023;20(4–6):53–55.

This ongoing column is dedicated to providing information to our readers on managing legal risks associated with medical practice. We invite questions from our readers. The answers are provided by PRMS (www.prms.com), a manager of medical professional liability insurance programs with services that include risk management consultation and other resources offered to health care providers to help improve patient outcomes and reduce professional liability risk. The answers published in this column represent those of only one risk management consulting company. Other risk management consulting companies or insurance carriers might provide different advice, and readers should take this into consideration. The information in this column does not constitute legal advice. For legal advice, contact your personal attorney. Note: The information and recommendations in this article are applicable to physicians and other health care professionals so “clinician” is used to indicate all treatment team members.

Question

I understand that patient suicide is the leading cause of malpractice lawsuits against psychiatrists. What specific strategies do you recommend for increasing patient safety?

Answer

Suicide has consistently been in the top two most frequent identifiable causes of loss in lawsuits against psychiatrists. The other cause of loss consistently in the top two is psychopharmacology. There are specific risk management strategies to improve patient safety when working with patients at risk for suicide, and implementation of these strategies decreases clinicians’ professional liability risk.

Standard of Care Expectations

Patients with suicidal behaviors are high-risk patients who present complex and difficult issues for the treating clinician. To understand your risk exposure when treating patients with suicidal behaviors, you need to understand the standard of care expectations, which can be summarized as identifying suicide risk and treating appropriately.

You are NOT expected to predict whether a particular patient will attempt suicide; courts do not expect impossible powers of prediction. However, the legal concept of “foreseeability” is part of the liability determination in a medical malpractice lawsuit. Foreseeability in this instance is related to whether the clinician performed an adequate suicide risk assessment and implemented appropriate safety measures based on that assessment. That is, based on the information available, did the clinician know or should they have known that the patient was at risk of suicide, and, if such foreseeability existed, did the clinician take appropriate steps in response?

For example, when discharging an inpatient from hospitalization due to suicidal ideation, one cannot predict that a suicide will or will not occur after discharge—there is no crystal ball. However, one CAN foresee that the failure to assess the patient for suicidality prior to discharge may lead to a substantial risk of injury. What is expected, as in any psychiatrist-patient interaction, is that the psychiatrist will meet the standard of care. In any particular instance, the standard of care encompasses a range of acceptable treatment options and requires the exercise of the clinician’s professional judgment. The exercise of professional judgment alone when choosing among acceptable treatment alternatives will not support an allegation of the breach of the standard of care.

To determine whether the standard of care was met in a lawsuit that results from a patient suicide, the clinician’s actions will be assessed by reviewing certain factors, including, but not limited to:

- Whether there was adequate identification and evaluation of suicide risk indicators and protective factors for the patient with suicidal behaviors;

- Whether a reasonable treatment plan was developed based on the assessment of the patient’s clinical needs;

- Whether the treatment plan was appropriately implemented and modified, based on an ongoing assessment of the patient’s clinical status;

- Whether the psychiatrist was professionally current regarding the assessment and treatment of patients with suicidal behaviors;

- And whether documentation in the patient record was adequate to support that appropriate care was provided in terms of the assessment, treatment, and ongoing monitoring of the patient.

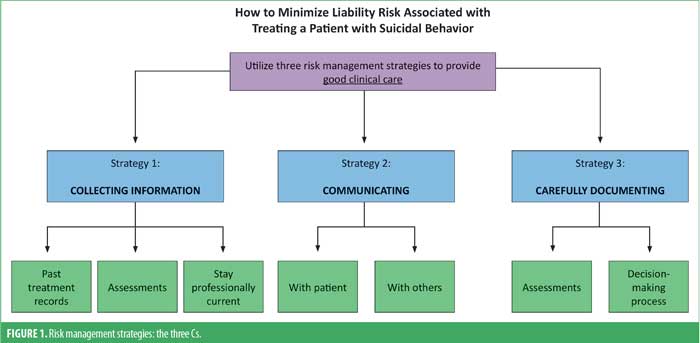

Risk Management Strategies: The Three Cs

There are three proven risk management strategies to decrease risk related to treating patients with suicidal behaviors that mirror best practices in clinical care: collecting information, communicating, and carefully documenting (Figure 1).

Collecting information. Assess patients at significant points in treatment. In addition to your initial assessment, you’ll need to assess whenever there is a change in observation level, at other appropriate times, and prior to discharge.

Explore the patient’s clinical history and past treatment. Try to obtain prior treatment records where possible, and document attempts to get records and information. While treatment recommendations might not be altered based on previous treatment information, past records can give the clinician a more comprehensive and nuanced context in which to understand the patient.

Utilize a specific suicide assessment methodology or resource when assessing for suicidality. This is strongly recommended as a risk management and patient safety action. Such standardization reduces error and makes it less likely that important information will be overlooked. One such resource is the Five-step Evaluation and Triage (SAFE-T) protocol, which is available on the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMSHA) website.

Keep digital issues in mind. We know that patients are able to find websites that will assist them in completing a suicide, and there is a comprehensive discussion of suicide methods on Wikipedia. We also know that patients have attempted suicide on camera during telemedicine sessions. Clinicians should get the patient’s exact location at the beginning of every remote session for the unlikely event in which emergency services need to be called.

Stay current on treatment options. This can be done via continuing education, journal articles, etc. Also, be sure that you know the criteria and procedure for involuntary hospitalization in your jurisdiction, and be sure you know the exact definition of “close observation,” as it can vary greatly by facility.

Communicating. Do not rely on “no-harm” or suicide prevention contracts. These agreements cannot take the place of an adequate suicide risk assessment. Although it may be appropriate for a “no-harm” contract to be one part of a comprehensive treatment plan, it is the clinician’s responsibility to evaluate the patient’s overall suicide risk and the patient’s ability to participate in the treatment plan.

Communicate with other healthcare professionals. Do not hesitate to obtain consultation when additional expertise would be useful in making treatment decisions. You may need to communicate with treatment team members for inpatients, with an outpatient therapist in a collaborative relationship, or with a covering psychiatrist.

Communicate with a patient’s family. Information obtained from communication with a patient’s family can be a critical part of understanding the patient’s condition and developing and implementing a reasonable treatment plan. Some clinicians, wishing to zealously protect a patient’s confidentiality, erroneously believe they cannot listen to what family members have to share about a patient, but listening to others does not constitute a breach of confidentiality and may provide invaluable information and insight into the patient’s true suicide risk. If the patient consents to the family’s involvement in treatment, the family should be informed about the potential for suicide and about risk factors that may increase the potential for risk. Even if the patient does not provide consent, consider alerting family members to the risk of outpatient suicide when the risk is significant, family members do not seem to be aware of the risk, and the family might contribute to the patient’s safety.

Discharge planning should be completed with the patient involved. The clinician is responsible for evaluating the patient’s overall suicide risk and their ability to participate in the treatment plan. Family and significant others should be involved in the discharge planning when appropriate. Discharge planning should include:

- Safety plan, including education of the patient and family so they know what to look for in terms of a crisis and what to do if they see symptoms appear

- Removal of weapons

- Plan for aftercare

- Resources.

Carefully documenting. Clinicians should document so that another professional could review the record and understand not only what happened in treatment, but also why. Under this analysis, information about what actions were not taken is as important as the information about what actions were taken.

The primary purpose of the clinical record is continuity of care; subsequent treaters need to know what happened in your treatment and why. However, documentation is also important in terms of defending lawsuits and administrative actions. Plaintiff attorneys do not like to take cases where good care is documented, as they will not be able to make up their own stories of what happened in your treatment, and it will be more difficult to find an expert to criticize your care. Even if a plaintiff attorney takes the case, treating clinicians are given a great deal of deference by the courts and juries, as long as they are provided with some understanding of why specific treatment options were chosen. That basis has already been created by the clinician—years prior—by contemporaneously documenting the basis for the clinical decision-making. Juries understand that contemporaneous documentation was done when there was no knowledge of the harm, so it is accurate rather than self-serving.

In Part 2, we will discuss post-suicide risk management issues.