by Erika D. Driver-Dunckley, MD; Nan Zhang, MS; Holly A. Shill, MD; Shyamal H. Mehta, MD, PhD; Christine M. Belden, PsyD; Edward Y. Zamrini, MD; Kathryn Davis; Thomas G. Beach, MD, PhD; and Charles H. Adler, MD, PhD

Drs. Driver-Dunckley, Mehta, and Adler are with the Department of Neurology of the Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Center at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona. Zhang is with the Section of Biostatistics at the Mayo Clinic in Scottsdale, Arizona. Shill is with the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Arizona. Belden, Zamrini, Davis, and Beach are with the Banner Sun Health Research Institute in Sun City, Arizona.

Funding: The Brain and Body Donation Program has been supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (no. U24 NS072026, National Brain and Tissue Resource for Parkinson’s Disease and Related Disorders); the National Institute on Aging (no. P30 AG19610, Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Core Center); the Arizona Department of Health Services (contract no. 211002, Arizona Alzheimer’s Research Center); the Arizona Biomedical Research Commission (contract nos. 4001, 0011, 05-901, and 1001, the Arizona Parkinson’s Disease Consortium); and the Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Abstract: Background: The Movement Disorder Society’s Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS), Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease–Autonomic (SCOPA-AUT), Mayo Sleep Questionnaire, Epworth Sleepiness Scale, and Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q) are validated instruments for assessing signs and symptoms of Parkinson’s disease (PD). Objective: We sought to determine whether responses on the MDS-UPDRS correlate with responses to other scales used in patients with PD. Design: Study subjects were enrolled in the Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders (AZSAND). Participants were selected if they had completed all scales within a one-month window. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were calculated. Results: A total of 96 eligible subjects were identified. High correlation (r-values) was found between the SCOPA-AUT and MDS-UPDRS excessive saliva (0.73; p<0.001), constipation (0.62; p<0.001), and swallowing (0.59; p<0.001) questions. The r-values for the NPI-Q and MDS-UPDRS depression and anxiety questions were 0.53 (p<0.001), and 0.67 (p<0.001). Conclusion: MDS-UPDRS correlates well with some but not all questions from the SCOPA-AUT and NPI-Q. This work emphasizes the importance of employing multiple methods for assessing nonmotor symptoms in patients with PD.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, MDS-UPDRS, SCOPA-AUT, ESS, MSQ, NPI-Q

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2019;16(9–10):27–29

The clinical spectrum of Parkinson’s disease (PD) includes multiple nonmotor symptoms (NMS), including mood changes, sleep disturbances, cognitive decline, and autonomic dysfunction.1 In clinical practice, due to time constraints on patient care, adequately addressing all of these symptoms can be difficult. Currently, there are several patient assessment scales available that can help practitioners identify and manage NMS, ultimately enabling them to improve the quality of care and quality of life for their patients with PD.

The Movement Disorder Society’s Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS) is a comprehensive, reliable, validated and popular instrument for assessing motor and NMS in patients with PD.2 Other scales used to assess NMS in PD include the Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson’s Disease—Autonomic (SCOPA-AUT),3 the Mayo Sleep Questionnaire (MSQ),4 the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS),5 and the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Questionnaire (NPI-Q).6 The NPI-Q, in particular, is an informant-based assessment of neuropsychiatric symptoms that is both brief to administer and reliable.6 The utility of each of these assessment scales ultimately depends upon how reliably they reflect ongoing symptoms of PD. Prior studies have evaluated correlations between the MDS-UPDRS and quality of life measures; however, there have been no direct studies comparing the MDS-UPDRS with other scales commonly used to assess NMS in PD.7,8

We herein report the findings of our study correlating specific responses on the MDS-UPDRS with respective questions on the SCOPA-AUT, MSQ, ESS, and NPI-Q in patients with PD.

Methods

All subjects signed informed consent forms and were enrolled in the Arizona Study of Aging and Neurodegenerative Disorders, an ongoing longitudinal clinicopathologic study in the Banner Sun Health Research Institute Brain and Body Donation Program.9 All subjects completed yearly longitudinal clinical assessments and movement examinations by a movement disorders fellowship–trained neurologist. Clinically probable PD was diagnosed if the subject had two of the three cardinal signs (i.e., rest tremor, bradykinesia, cogwheel rigidity), no other symptomatic cause, and a response to dopaminergic medications. Individuals were selected for inclusion if they had completed all questionnaires, including the MDS-UPDRS, within a one-month window.

Statistical analysis. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were calculated between specific questions in the MSQ, ESS, SCOPA-AUT, and NPI-Q scales and their corresponding questions in the MDS-UPDRS.

Results

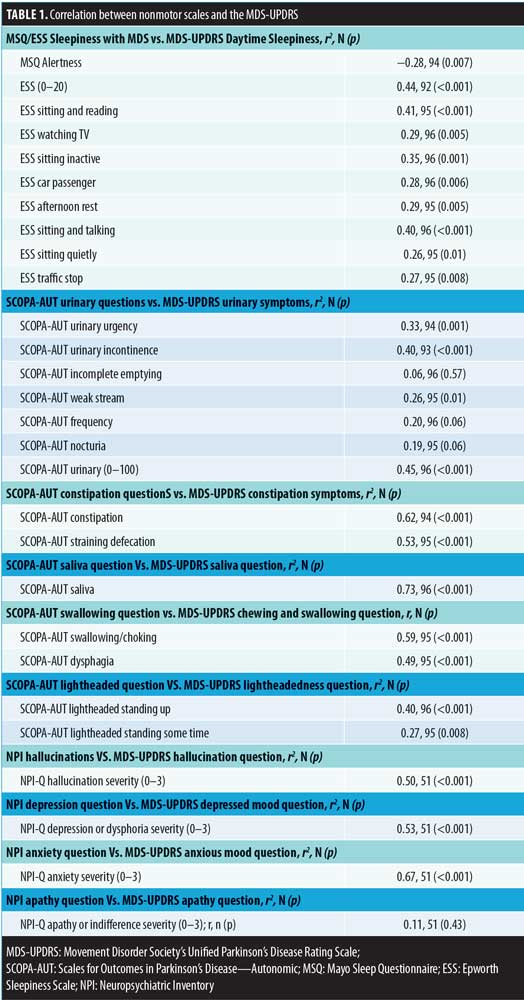

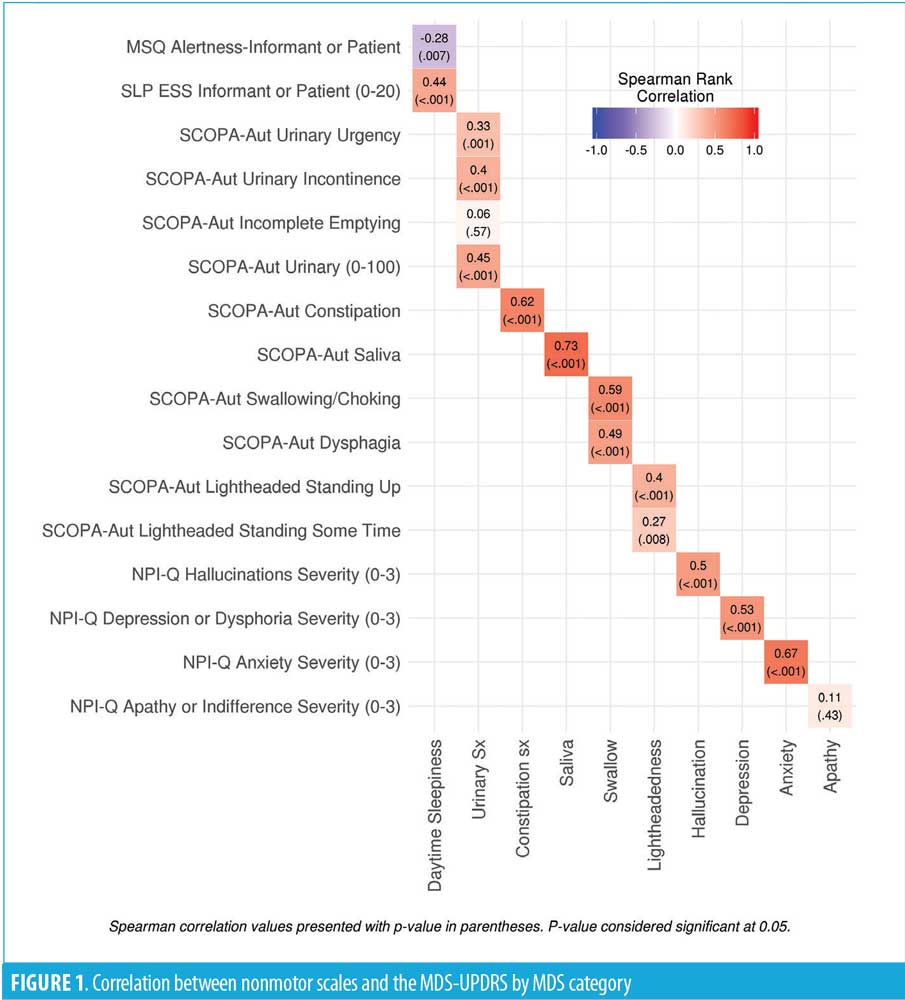

We identified 121 subjects with PD who completed the MDS-UPDRS assessment, of whom 96 had linked the MDS-UPDRS with the other questionnaires. At the time of the MDS-UPDRS, the subjects had a mean age of 74.7 (7.5) years, and 68.8 percent were male. The mean disease duration was 10.2 (6.6) years with a mean Hoehn–Yahr stage of 2.4 (0.8) [range: 0–5]. All correlations are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1.

All correlations are shown in Table 1 and Figure 1. Significant cross-assessment correlations were noted between the SCOPA-AUT and MDS-UPDRS excessive saliva (0.73; p<0.001), constipation (0.62; p<0.001), and swallowing (0.59; p<0.001) questions. In addition, the correlation between the NPI-Q and MDS-UPDRS depression question was 0.53 (p<0.001), while that for anxiety was 0.67 (p<0.001). There was poor correlation between the MDS-UPDRS and other assessment scales, including the SCOPA-AUT urinary symptoms and lightheadedness, NPI-Q apathy, MSQ, and ESS alertness and sleepiness, in that all had correlations of less than 0.50 (range: 0.06–0.50).

Discussion

Multiple validated questionnaires are currently used to assess NMS in PD. However, to our knowledge, no studies have correlated responses to these questionnaires with the validated MDS-UPDRS to determine their reliability. In this study, we correlated specific responses on the MDS-UPDRS with respective questions on the SCOPA-AUT, MSQ, ESS and the NPI-Q in patients with PD. The MDS-UPDRS correlation with other nonmotor scales was strongest with the SCOPA-AUT excessive saliva, constipation and swallowing questions along with the NPI anxiety and depression assessments. In contrast, we found relatively poor correlations between the MDS-UPDRS and the MSQ alertness question, NPI-Q apathy question, and the SCOPA-AUT lightheadedness and a subset of the urinary questions. This striking result highlights the limitations of relying on a single assessment for patient evaluation and treatment.

Initially, we expected to find more correlations between the specific MDS-UPDRS questions and the other scales. However, we found the opposite to be true. There may be multiple reasons for the differences and poor correlation between assessment scales. One major difference is that the MDS-UPDRS was administered by the movement disorder neurologist directly during the clinical assessment, while all other scales were completed independently by the patient or informant. Although these questionnaires are self-explanatory, it’s possible that subjects and informants did not understand how to complete the questionnaires accurately. The clinician was able to clarify any misunderstandings over the questions in parts I and II of the MDS-UPDRS with the subjects. This could be potentially avoided in the future by having questionnaires reviewed at the time at which the MDS-UPDRS is completed, but while that might improve correlations, it might also defeat the purpose of having self-reported questionnaires for research or clinical practice. Another possible explanation for the lack of correlation for some questions is the inherent difference in the scales. The SCOPA-AUT, MSQ, ESS, and NPI-Q have multiple detailed questions and subquestions assessing one particular NMS, while the MDS-UPDRS has just a single question. It is not unusual, however, that there was a lack of correlation between the MDS-UPDRS and NPI-Q apathy question since the NPI-Q is an entirely informant-based questionnaire and caregivers might not recognize the subtle signs of apathy to the degree that a clinician would.

NMS can be difficult to assess in PD patients in a timely manner. Utilization of the various scales available is important to obtain a comprehensive account of patients’ NMS. The MDS-UPDRS provides a comprehensive overview of all motor symptoms and NMS that PD patients experience. With its reliability and reproducibility, the MDS-UPDRS remains the popular choice for use in movement disorder clinics, particularly for screening. The SCOPA-AUT, MSQ, ESS, and NPI-Q are additional, useful, and helpful scales to further clarify PD patients’ NMS. With clinical time constraints, these scales can be completed prior to the appointment, which would allow for the practitioner to then further specifically address the bothersome symptoms identified in the questionnaires.

This work thus emphasizes the importance of utilizing multiple methods for assessing NMS in patients with PD.

References

- Adler C, Beach T. Neuropathological basis of non-motor manifestations of Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2016; 31(8):1114–1119.

- Goetz C, Tilley B, Shaftman S, et al, Movement Disorder Society UPDRS Revision Task Force. Movement Disorder Society–sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (MDS-UPDRS): scale presentation and clinimetric testing results. Mov Disord. 2008;15;23(15):2129–2170.

- Visser M, Marinus J, Stiggelbout A, et al. Assessment of the autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease: the SCOPA-AUT. Mov Disord. 2004;19(11):1306–1312.

- Boeve B, Silber M, Ferman T, et al. Validation of a questionnaire for the diagnosis of REM sleep behavior disorder. Neurology. 2002;58(Suppl 3):A509.

- Johns M. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14(6):540–545.

- Kaufer D, Cummings J, Ketchel P, et al. Validation of the NPI-Q, a brief clinic form of the Neuropsychiatry Inventory. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;12(2):233–239.

- Skorvanek M, Rosenberger J, Minar M, et al. Relationship between the non-motor items of the MDS-UPDRS and the Quality of Life in patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Neurol Sci. 2015;353(1–2):87–91.

- Martinez-Martin P, Rodriguez-Blazquez C, Forjaz M, et al. Relationship between the MDS-UPDRS domains and the health-related quality of life of Parkinson’s disease patients. Eur J Neurol. 2014;21(3):519–524.

- Beach T, Sue L, Walker D, et al. The Sun Health Research Institute Brain Donation Program: description and experience, 1987–2007. Cell Tissue Bank. 2008;9(3):229–245.