by Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD

by Donna Vanderpool, MBA, JD

Ms. Vanderpool is Director of Risk Management at Professional Risk Management Services (PRMS)

FUNDING: No funding was provided for the preparation of this article.

DISCLOSURES: The author is an employee of PRMS. PRMS manages a professional liability insurance program for psychiatrists.

This ongoing column is dedicated to providing information to our readers on managing legal risks associated with medical practice. We invite questions from our readers. The answers are provided by PRMS (www.prms.com), a manager of medical professional liability insurance programs with services that include risk management consultation and other resources offered to health care providers to help improve patient outcomes and reduce professional liability risk. The answers published in this column represent those of only one risk management consulting company. Other risk management consulting companies or insurance carriers might provide different advice, and readers should take this into consideration. The information in this column does not constitute legal advice. For legal advice, contact your personal attorney. Note: The information and recommendations in this article are applicable to physicians and other health care professionals so “clinician” is used to indicate all treatment team members.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2021;18(7–9):50-51

Question:

I’ve never had a clear understanding of “the standard of care.” What exactly is it, what is its relevance, and how is it determined? Lastly, is there a different emergency standard of care to use during disasters or public health emergencies?

Answer:

Clinicians need to understand the concept of the standard of care. The standard of care is the benchmark that determines whether professional obligations to patients have been met. Failure to meet the standard of care is negligence, which can carry significant consequences for clinicians.

What the Standard of Care Is

The standard of care is a legal term, not a medical term. Basically, it refers to the degree of care a prudent and reasonable person would exercise under the circumstances. State legislatures, administrative agencies, and courts define the legal degree of care required, so the exact legal standard varies by state. The vast majority of states follow the national standard,1 such as this from Connecticut Code §52-184c: “…that level of care, skill and treatment which, in light of all relevant surrounding circumstances, is recognized as acceptable and appropriate by reasonably prudent similar health care providers.”

Very few states have retained the locality standard, whether it is based on the same community, same or similar community, or same state. Another option is for the state to adopt the same or similar community standard for generalists, but the national standard for specialists. Given the prevalence of the internet for research and telehealth for consultation, the risk management advice is to aim to meet the national standard.

Note that the standard of care is not optimal care. Rather, it is a continuum, with barely acceptable care at one end, and the ultimate in care at the other end. In terms of malpractice liability, physicians just need to make it onto the continuum, even if near the barely acceptable care end. Of course, in terms of patient safety and clinical outcomes, physicians should aim in the direction of optimal care.

Also keep in mind that physician discretion and clinical judgment remain important. Physicians should document their clinical judgment and decision-making so that their treatment can be understood, whether by subsequent treaters or even by expert witnesses in future litigation.

Relevance of the Standard of Care to Clinicians

The standard of care is relevant in medical malpractice lawsuits. To prevail in a malpractice case, the plaintiff must prove all four of the following elements:

Duty: The clinician owed a duty to meet the standard of care to the plaintiff patient.

Negligence: The clinician did not meet the standard of care.

Harm: The plaintiff suffered some type of harm—physical, emotional, and/or financial.

Causation: The plaintiff’s harm was caused by the defendant clinician’s failure to meet the standard of care

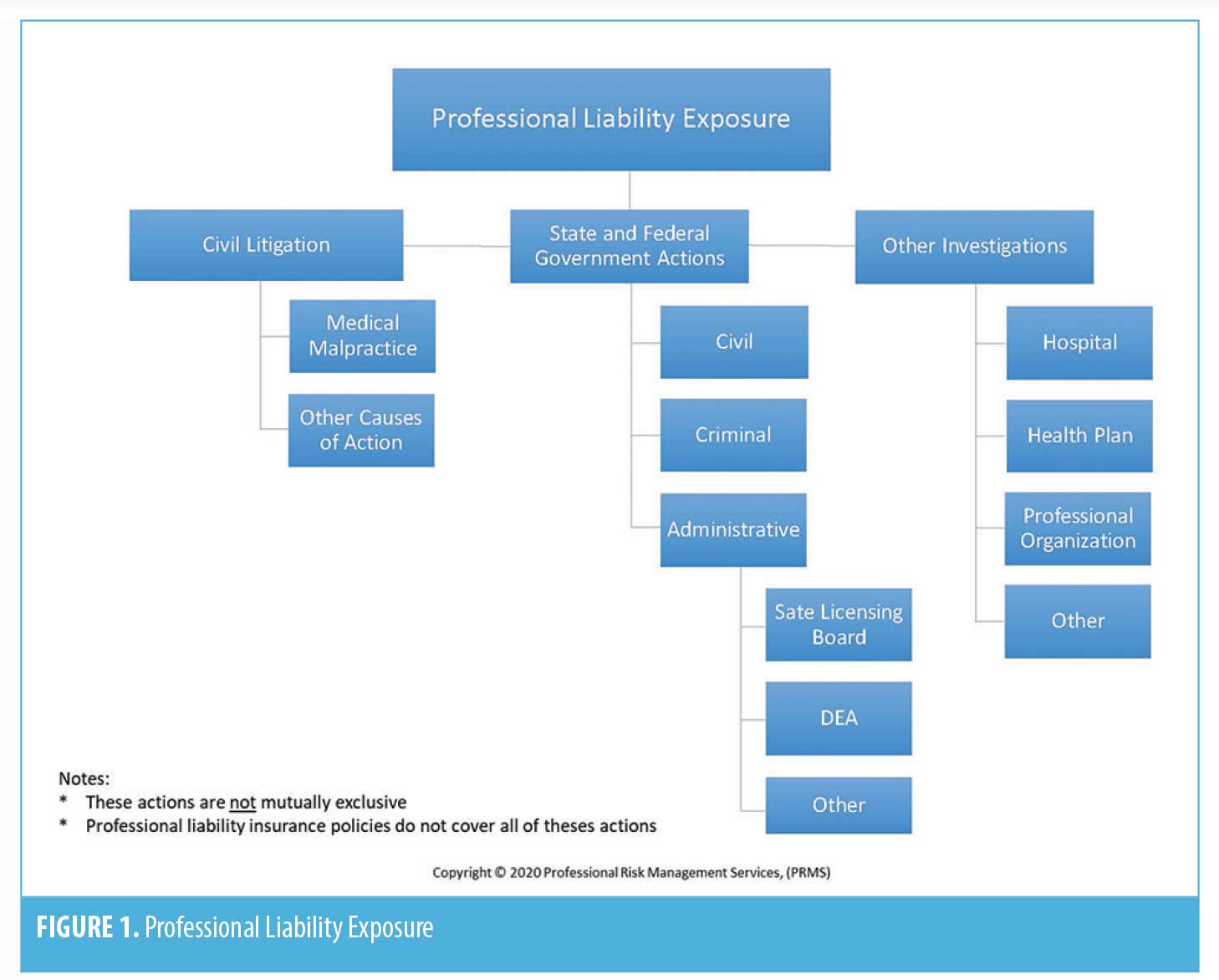

But the standard of care is not relevant in all liability actions that can be brought against clinicians. As can be seen in Figure 1, medical malpractice, where the standard of care is relevant, is only one of the many different types of actions that can be brought against psychiatrists.

Note that the standard of care—what reasonably prudent similar healthcare providers are doing under similar circumstances—is not relevant in government investigations. In those cases, what other psychiatrists are doing is irrelevant; the sole question is whether the psychiatrist under investigation followed the law.

How the Standard of Care Is Determined

There are a variety of factors that can evidence the applicable standard of care in any clinical situation. In descending order of relevance, these factors are:

- Statutes: federal and state, such as prescribing laws

- Regulations: federal and state, such as confidentiality regulations

- Court opinions: such as duty to warn of dangerous patient case decisions

- Other regulatory statements: federal and state, such as guidelines from licensing boards

- Authoritative clinical guidelines: in and of themselves, guidelines are not the standard of care, but are a factor that will be sued to determine the standard of care. Just as following guidelines does not preclude negligence, deviating from guidelines does not equal negligence. If authoritative clinical guidelines (not utilization review guidelines) are not followed, the reason and clinical judgment should be documented.

- Policies and guidelines from professional organizations, such as from the APA or AACAP

- Journal/research articles

- Accreditation standards

- Facility policies and procedures

In litigation, each side’s expert witness will testify as to the applicable standard of care, based on the factors listed above, as well as their own clinical experience. The fact finder, the jury (or the judge in a case without a jury), will decide which side’s expert is determinative.

Emergency Standard of Care Not Needed

There is no need for a different standard of care during emergencies or disasters. As discussed above, the standard of care is basically what a reasonably prudent similar healthcare provider would do under similar circumstances. In light of this, there is flexibility for the standard of care to be tailored to the specific circumstances, such as with an emergency or other disaster.

Conclusion

The risk management advice is to keep current in clinical practice by staying up to date on the above factors that evidence the standard of care. By doing so, should a clinician face a malpractice lawsuit, that clinician should be able to demonstrate that his or her professional obligations to patients were met.

Reference

- Cooke B, Worsham E, Reisfield G. The elusive standard of care. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2017;45:358–364.