by Kari Harper, MD, and Julie P. Gentile, MD, MBA

Dr. Harper is Assistant Professor and Assistant Training Director of Child/Adolescent Fellowship at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio. Dr. Gentile is Professor and Chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio.

Funding: No funding was provided for this study.

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to the content of this article.

Innov Clin Neurosci. 2022;19(7–9):28–31.

Department Editor

Julie P. Gentile, MD, is Professor and Chair of the Department of Psychiatry at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio.

Editor’s Note

The patient cases presented in Psychotherapy Rounds are composite cases written to illustrate certain diagnostic characteristics and to instruct on treatment techniques. The composite cases are not real patients in treatment. Any resemblance to a real patient is purely coincidental.

Abstract

The child patient who presents for psychiatric evaluation due to aggressive behavior poses specific challenges to the treating psychiatrist. Boundary violations, devaluation of relationships and social skills, and transference/countertransference issues are some of the challenges that may arise during the psychiatric treatment of the aggressive child patient. The child who displays aggression may have complex challenges, including major transitions, insomnia, trauma history, custody considerations, and family disruption, among others. This article reviews the treatment dynamics created by the child patient with history of aggression, as well as the approaches that the psychiatrist can utilize in a therapeutic manner.

Keywords: Child psychiatry, child psychotherapy, bullying, aggression, Social Awareness Theory, cognitive triangle, Beck, parental self-efficacy, adaptive coping skills, emotional regulation

Child/adolescent psychiatrists are often faced with children who are aggressive or perpetrators of bullying. Farrington1 defines bullying as repeated oppression, psychological or physical, of a less powerful person by a more powerful one. Bullying, according to the National Center Against Bullying (NCAB), is “an ongoing and deliberate misuse of power in relationships through repeated verbal, physical, and/or social behavior that intends to cause physical, social and/or psychological harm.”2 These patients can produce unique diagnostic, therapeutic, and practical challenges. Bullying can happen in-person or virtually, using various digital platforms and devices. Bullying of any form, for any reason, can have immediate, mid-, and/or long-term effects on those involved, including bystanders. Psychotherapy is proven to help children and families understand and resolve problems, modify behavior, and make positive changes in their lives. There are multiple types of psychotherapy that involve various approaches, techniques, and interventions.

Fictional Case Vignette

P was an 11-year-old male adolescent with a history of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) combined type, oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), who presented for psychotherapy and medication management, accompanied by his mother, Ms. B. Ms. B expressed concern about aggression, stating that P tended to be a “bully” at school and in their neighborhood, often hitting and pushing others. When getting to know P better, it was clear that he often misinterpreted neutral or positive social interactions as negative ones and had poor self-esteem. During session eight, Ms. B and P relayed some concerning interactions from the week.

Dialogue 1

Psychotherapist: How has this week gone?

P: Fine.

Ms. B: Not fine. He hasn’t been listening at all. I don’t know what to do anymore. When I ask him to do anything, he just refuses or tries to negotiate, and it always turns into an argument.

P (scowling): It does not! If you would just let me watch YouTube it would be fine!

Ms. B: We’ve tried behavior charts, taking things away, rewards…. Nothing seems to work. And he got into a fight in the neighborhood this week. Now he says he doesn’t have any friends anymore.

Psychotherapist: P, what happened?

P (arms crossed): I don’t know.

Ms. B: The doctor needs to know.

P (fists clenched and face red): J got a new scooter. Everyone was trying it out and saying how nice it was. He asked me if I wanted to ride it. He obviously thought it was better than mine, so I punched him. It was his fault!

Psychotherapist: Wow, you look and sound really mad right now. What other emotions do you feel?

P: I’m just mad!

Psychotherapist: How do you think J and the other kids felt when you hit J?

P: Probably mad, but it was his fault! (Tearing up now, P refuses to discuss the incident further.)

Practice Point: Beck’s Cognitive Triad Requires Emotional Awareness and Understanding of Interconnectivity of the Triad

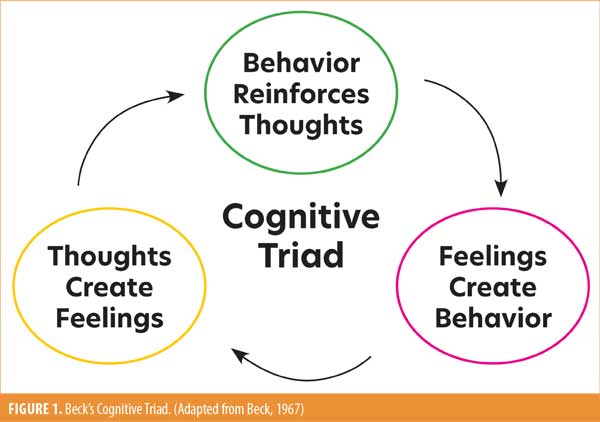

Beck’s Cognitive Triad is a cognitive-therapeutic view of the three key elements of a person’s belief system present in depression. (Figure 1).3 This triad forms part of Beck’s Cognitive Theory of Depression; it is part of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in the treatment of negative automatic thoughts. The cognitive triangle illustrates how thoughts, emotions, and behaviors are interrelated. When a person changes their thoughts, they can also change their emotions and behaviors.3

Social awareness is an individual’s ability to understand people, social events, and the processes involved in navigating interpersonal interactions.4 Social awareness includes the ability to understand others’ perspectives and be empathic to diverse cultures and backgrounds. Social awareness is crucial to success in educational and occupational environments. Children with social awareness are better equipped to adapt to educational and social settings; they can engage in constructive communication and resolve conflicts.5

Core concepts of the cognitive triangle include self-awareness and the ability to be aware of and consider one’s own thought processes. If the patient develops this skill set, they can begin to manage those thoughts, feelings, and resulting behaviors. Our behaviors often feel outside our control. Our negative thoughts can be on autopilot, and when addressed appropriately, they can be interrupted, so we can then focus on them and ensure they are based in reality. Therefore, they can be analyzed, understood, and altered as needed. These skills can help eliminate the perceived need for bullying behaviors.

Clinical Pearls

- Beck’s Cognitive Triad represents the relationship of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

- Automatic thoughts must be identified and altered as appropriate, allowing a sense of control over one’s behavior.

- Self-awareness and social awareness are core concepts contributing to the utilization of the cognitive triangle in therapy.

Clinical Vignette, Continued

Ms. B reported that P seemed to “rule the household,” especially when Mr. B was at work or out of town. She said raising P was different than raising her now adult daughter, and P often used threatening language or lunged at her, similar to his bullying behaviors with peers. In the initial session, alone with the psychotherapist, Ms. B stated that she had a history of depression and anxiety, including postpartum depression after P’s birth. She also reported that her childhood had been difficult, with an absent father and an authoritarian mother. During session 15, Ms. B asked to speak with the psychotherapist alone.

Dialogue 2

Ms. B: P has been more irritable lately. It seems like all we ever do is argue. I don’t know what to do or how to talk with him.

Psychotherapist: In what ways have you noticed he has been more irritable?

Ms. B: When he is playing video games and I ask him to do anything, even come to dinner, he gets really upset. At first, he just refuses. Then he yells and throws things.

Psychotherapist: How are you feeling when this happens, and how do you respond?

Ms. B: I feel helpless to do anything other than negotiate with him or give in to what he wants. I’m really discouraged.

P joined the session.

Psychotherapist: P, how have you been doing this week?

P: Fine. Can we play with Legos now?

Psychotherapist: I wanted to talk to you about some things Mom said first.

P (reluctantly): Okay.

Psychotherapist: Mom tells me there have been a lot of arguments lately. Have you noticed that too?

P: Well, yeah. She just needs to let me do what I want!

Psychotherapist: I would like to find a way for you and Mom to argue less frequently. Do you think that would be better?

P: Yeah, I guess so. Are we done talking yet?

Practice Point: Improving Parental-Self Efficacy Can be an Effective Way to Enhance the Parent-Child Relationship and to Improve the Child’s Behavior

Maternal self-efficacy, a mother or parent’s belief in their ability to effectively manage the various tasks and situations of parenthood,6 has been found to predict high levels of compliance, enthusiasm, and affection toward the mother and low levels of negativity in children.7 Increasing parents’ self-efficacy and verbal responsiveness can decrease children’s externalizing behaviors.8 Parental self-efficacy has been found to be important across ages, from infant to adolescent, for parental competence.9

Parents with higher levels of parental self-efficacy have more positive interactions with their children, are more involved in activities, are better able to set limits, monitor their children’s activities more often, exhibit warmth toward their children, and were more responsive to their children.9 Interventions targeting parental self-efficacy showed some benefit for children with ADHD and with behavior problems.8,9 Mothers who are stressed or depressed have been found to exhibit lower parental self-efficacy and display less effective parenting.

A study by Loop et al10 suggests that reminding parents of parenting techniques that involve being attentive to emotions, discussing goals, and teaching coping skills can help parents be more engaged and positive with their children. It also suggests that when parents are more engaged and positive during frustrating situations, children might be better able to stay on task and more positive as well.

Clinical Pearls

- Parents who are stressed or depressed have lower parental self-efficacy.

- Improving parental self-efficacy can improve the relationship between parent and child and lower stress for the parent.

- Reminding parents how to be attentive to the child’s emotions and teaching coping skills can contribute to increased positive interactions.

Clinical Vignette, Continued

Over the course of psychotherapy, P also developed symptoms of major depressive disorder (MDD). P had difficulty with the move and introduction to a new peer group, leading to low self-esteem and depressed mood. As P displayed more anger, it became clear his irritability was a symptom of a depressive episode. P’s demeanor during therapy changed, and he became more resistant, as evidenced by the events of session 20.

Dialogue 3

Ms. B, P, and the psychotherapist talked first about the week. Ms. B left the room. The psychotherapist presented an activity focusing on emotions to P.

P: No, I just want to build with Legos.

Psychotherapist: We can build after we do this. It will take 10 minutes or less.

P walked toward the Legos and started getting them out. The psychotherapist put away the box of Legos.

P: What are you doing? I don’t want to do that!

P stomped to the other side of the room and sat under a desk with his arms crossed and a look of anger on his face.

Psychotherapist: I can see you are really angry.

(Pause)

You had a different idea of what we were going to do today.

(Pause)

It’s hard to talk about how you are feeling. I can wait until you are ready.

(Pause)

After 25 minutes, the psychotherapist asked Mom to rejoin the session and explained what had occurred.

Psychotherapist: Is this how it goes at home?

Ms. B: Yes, very similar. If he doesn’t get to do things his way, he just won’t do anything.

Practice Point: Development of Adaptive Coping Strategies and Emotional Regulation May Help Reduce Depression and Anxiety and, Therefore, Aggressive Behavior

Results of a meta-analysis by Sendzik et al11 showed that youth with difficulties in emotional awareness had more difficulty with depression and anxiety. When children under the age of 12 years have difficulties with emotional awareness, they might have even more difficulty coping with normal anxiety or might experience more depression than their peers.11 Stoltz et al12 tailored an intervention to specific children focusing on cognitive skills, self-esteem, and reframing social situations to help reduce aggression.

In a meta-analysis examining the relationship between use of adaptive emotion regulation strategies (problem solving, acceptance, and cognitive reappraisal) and maladaptive emotion regulation strategies (avoidance, suppression, and rumination), the use of adaptive strategies trended toward lower depression and anxiety, while use of maladaptive strategies trended toward higher depression and anxiety.13 The authors pointed out that these cognitive and behavioral strategies, both adaptive and maladaptive, can be strengthened as the individual progresses along the developmental course. It might, therefore, be important to introduce adaptive strategies early, particularly for children already experiencing symptoms of depression and anxiety or having difficulty with emotional awareness.

Depressed adolescents have a need for psychotherapy and increased coping skills, especially cognitive skills.14 CBT and interpersonal therapy are both proven to be efficacious in treating children and adolescents with symptoms of depression.15

Clinical Pearls

- In children and adolescents, irritability and anger should be explored as signs of depression, anxiety, or another underlying cause.

- Children and adolescents with low emotional awareness have more difficulty coping with negative emotions and might be more likely to develop depression and anxiety disorders.

- Focusing on identifying and regulating emotions are important components of treating depression in children and adolescents.

Clinical Vignette Conclusion

Through both play and exploration of stressful events, P was able to begin recognizing the connections between his thoughts, emotions, and behaviors. As he became more aware of other’s feelings, he began to better understand their behaviors as well.

While Ms. B had tried many techniques in the past, she was open to reviewing various parenting techniques and trying again. The therapist also facilitated some conversations between Ms. B and P, focusing on exploring both parties’ emotions. Ms. B began to better understand why P was behaving in certain ways. Ms. B was also able to begin to tell P how his words and actions made her feel. P began to develop increased self-awareness and social awareness as a result. As Ms. B’s parental self-efficacy improved, she was able to implement parenting strategies more effectively. She began to report more positive interactions with P, and P began to report more positive feelings toward his mother. P expressed immense trust in Ms. B, which had not been obvious before.

Therapy with P was most successful when helping him to consider or reconsider his environment and recognize and regulate his own emotions. The psychotherapist, Ms. B, and P also began spending the first five minutes of therapy practicing various coping skills together, including yoga, exercise, coloring, and grounding techniques. Over the course of treatment, P also developed significant cognitive skills, allowing him to utilize adaptive strategies more effectively.

By the end of treatment, P had not been aggressive for several months, and he was getting along much better with his parents. He was able to regulate his own emotions, as evidenced by a decrease in behavioral problems documented and number of times sent to the office at school. P was also successful in sustaining several friendships over time. He even noted, when discussing other bullies at school, “Hurting people hurt people.”

References

- Farrington DP. Understanding and preventing bullying. Crime Justice. 1993;17:381–458.

- National Center Against Bullying (NCAB). Definition of bullying. https://www.ncab.org.au/bullying-advice/bullying-for-parents/definition-of-bullying/. Accessed 19 Feb 2022.

- Beck Institute. Introduction to Cognitive Behavior Therapy. https://beckinstitute.org/about/intro-to-cbt/. Accessed 19 Feb 2022.

- Greenspan S. Defining childhood social competence: a proposed working model. Advances Special Educ. 1981;3:1–39.

- Greenberg MT, Weissberg RP, O’Brien MU, et al. Enhancing school-based prevention and youth development through coordinated social, emotional, and academic learning. Am Psychol. 2003;58(6–7):466–474.

- Gross D, Rocissano L. Maternal confidence in toddlerhood: its measurement for clinical practice and research. Nurse Pract. 1988;13:19–29.

- Coleman PK, Karraker K. Maternal self-efficacy beliefs, competence in parenting, and toddlers’ behavior and developmental status. Infant Mental Health J. 2003;24(2):126–148.

- Roskam I, Brassart E, Loop L, et al. Stimulating parents’ self-efficacy beliefs or verbal responsiveness: which is the best way to decrease children’s externalizing behaviors. Behav Res Ther. 2015;72:38–48.

- Jones TL, Prinz RJ. Potential roles of parental self-efficacy in parent and child adjustment: a review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2005;25(3):341–363.

- Loop L, Roskam I. Do children behave better when parents’ emotion coaching practices are stimulated? A micro-trial study. J Child Family Studies. 2016;25;2223–2235.

- Sendzik L, Schafer OJ, Samson AC, et al. Emotional awareness in depressive and anxiety symptoms in youth: a meta-analytic review. J Youth Adolesc. 2017;46(4):687–700.

- Stoltz S, van Londen M, Deković M, et al. Effectiveness of an Individual school-based Intervention for children with aggressive behavior: a randomized controlled trial. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2013;41(5):525–548

- Schafer JO, Mehihorn C. Can personality traits predict musical style preferences? A meta-analysis. Pers Individ Differ. 2017;116:265–273.

- Puskar K, Sereika S, Tusaie-Mumford K. Effect of the teaching kids to cope program on outcomes of depression and coping among rural adolescents. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2007;16(2):71–80.

- Weersing VR, Jeffreys M, Do MT, et al. Evidence base update of psychosocial treatments for child and adolescent depression. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2017;46(1):11–43.